Signalment:

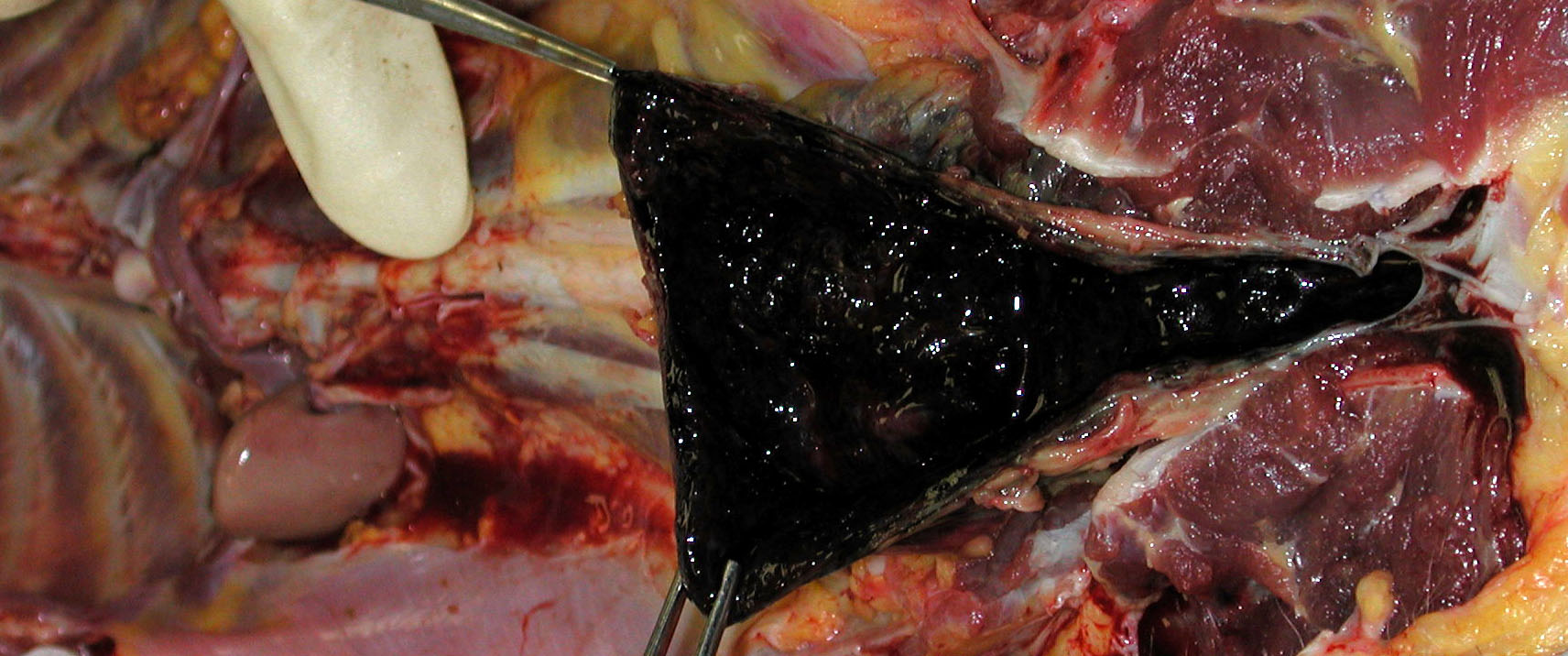

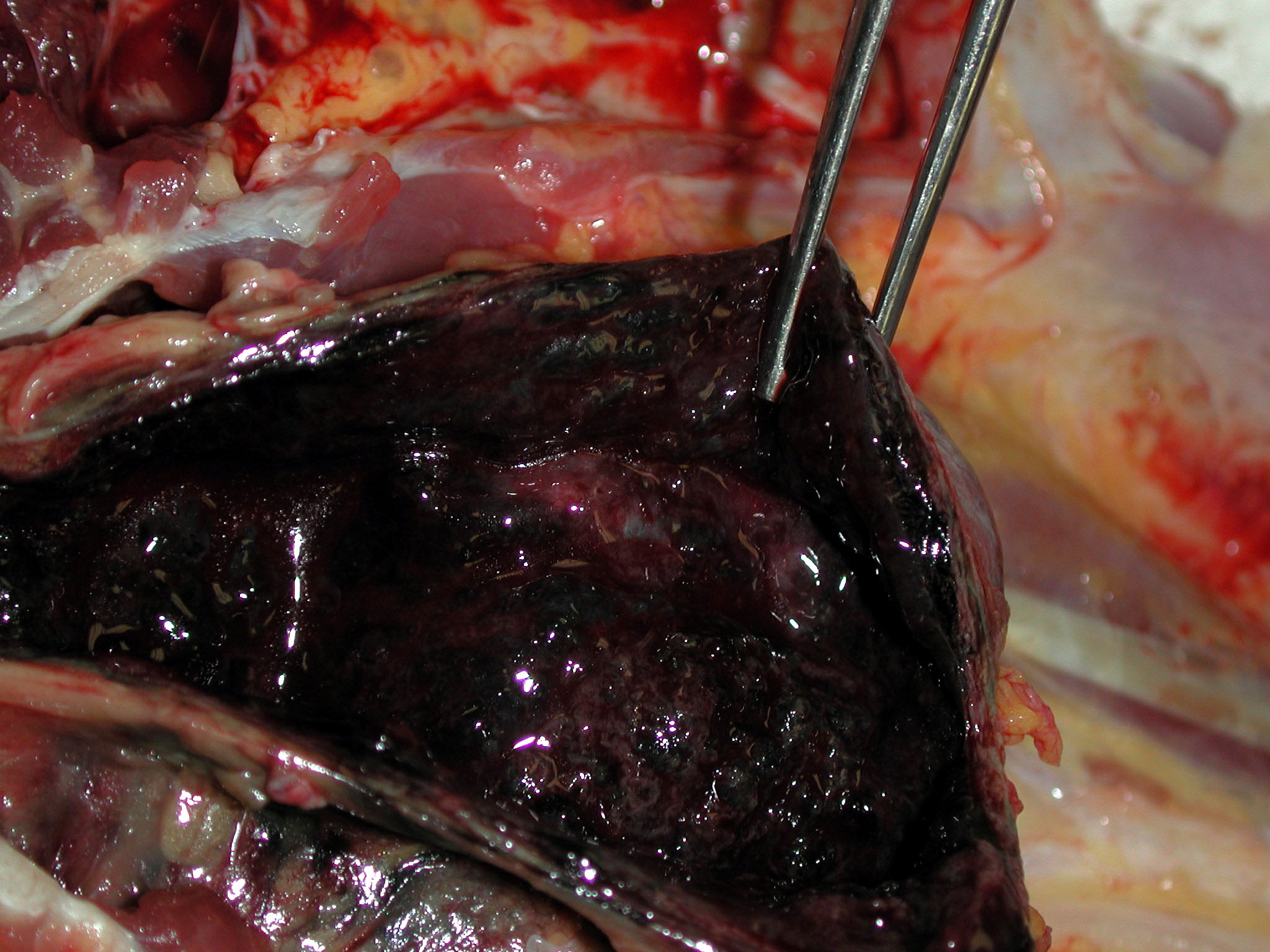

Gross Description:

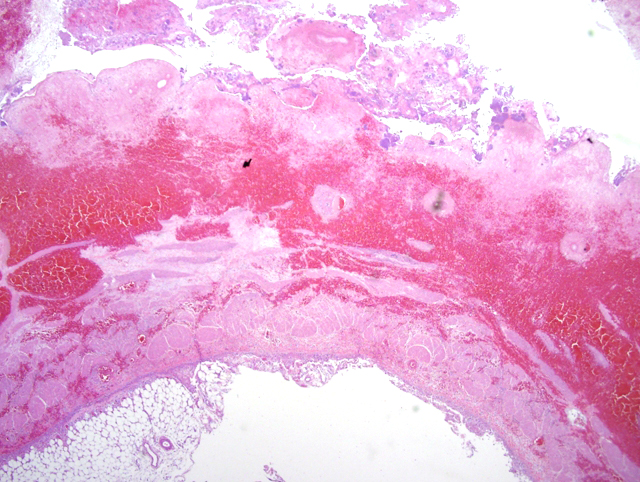

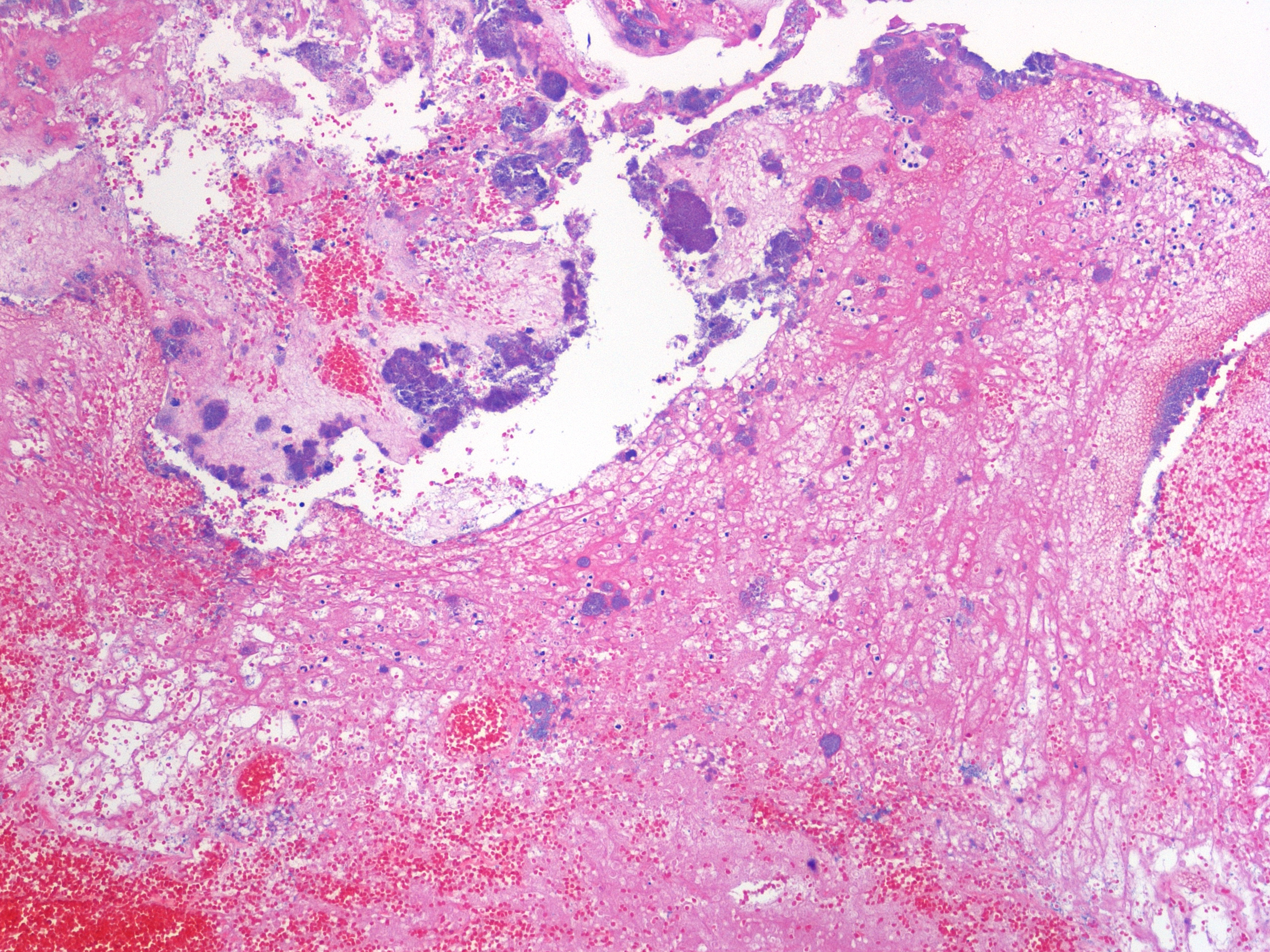

Histopathologic Description:

Additional significant histologic findings in the cynomolgus macaque included acute to subacute fibrinous polyserositis that included the urinary bladder, stomach, pancreas and mesentery. The inflammatory lesions on the serosal surfaces of the viscera were attributed to leakage of the contents from the necrotic urinary bladder into the abdomen (peritonitis).Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

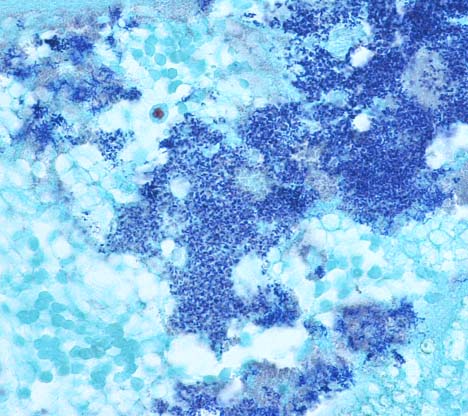

1. Urinary bladder: Cystitis, necrohemorrhagic, transmural, subacute, diffuse, severe, with fibrinonecrotic membrane, hemorrhage, edema, necrotizing vasculitis, thrombi, structural loss (perforation), and many Gram positive coryneform bacteria (Fig. 3-5).

2. Urinary bladder, serosa and mesentery: Serositis and peritonitis, necrotizing, subacute, diffuse, severe, with neutrophilic and histiocytic inflammation, marked mesothelial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, hemorrhage, fibrin and edema.

Lab Results:

Heart blood culture: No growth after 72 hours

Urine culture: Corynebacteriumsp.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Of the non-diphtheritic coryneform bacteria, several members of the Corynebacteria renale group, including C. renale (I), C. pilosum (II), and C. cystitidis (III), are opportunistic urinary tract pathogens in domestic animals and natural causes of cystitis, ureteritis, and ascending pyelonephritis in cattle. This condition in the bovid is commonly known as bacillary pyelonephritis.6,8,9 Animals may become predisposed to bacillary pyelonephritis through physical or chemical damage to the lower genitourinary tract caused by dystocia, urinary bladder paralysis, and urinary catheterization. Urinary tract infections are more common in females. These predisposing factors disrupt the hosts natural defenses, such as the mucosal barrier, and may allow initial colonization of tissue with coryneform bacteria. Hemorrhagic urethritis, cystitis, and pyelonephritis develop as a result of ascending urinary tract infection.6,8,10,14

This case displayed similarities to corynebacterial urinary tract infections in other animal species, including natural and experimental infections in cattle, goats, mice and rats.2,5,6,7,12 Infection with C. renale group bacteria in cattle in particular may affect all or part of the urinary tract. In the urinary bladder, typical lesions include mural thickening from infiltrating leukocytes and hemorrhage, vasculitis and fibrin thrombi, mucosal necrosis, ulceration and perforation, hemorrhage; and replacement of the mucosa by a fibrinonecrotic (diphtheritic) membrane.6,8

Several bacterial virulence factors may predispose animals to infection and progression of necrohemorrhagic urinary system lesions due to C. renale group organisms. Corynebacteria renale group organisms possess pili, allowing attachment to the urogenital mucosa and facilitating ascension of microbes into the bladder and kidneys. The bacteria produce urease and hydrolyze urea, which may be contributory to extensive ulceration of the mucosa and necrosis in the affected tissues.5,8,9,14 Thus, high protein diets and subsequently elevated urinary urea levels may predispose animals to disease because of the ability to hydrolyze urea.9

Host factors may also predispose animals to infection. In cattle, females are more predisposed to infection than males due to anatomic structure, hormonal influences, and risks associated with pregnancy or iatrogenic procedures; infection in bulls is rare.8 Females have short urethras, which decreases the anatomic barrier bacteria must overcome to reach the urinary bladder and kidneys, and urethral trauma associated with dystocia or catheterization may serve as initiating events for infection.8,10,14 Hormone-induced changes in female animals may serve as predisposing factors; high estrogen levels may affect the functional integrity of the epithelium in the urethra and urinary bladder; cattle with high estrogen levels that graze pastures are reportedly prone to infection with C. renale.8,9 In some animal species, such as the sow, estrogen causes an elevation in the urine pH, which may produce an alkaline environment optimal for expression of bacterial pili and enhanced microbial survival and proliferation.8,14 Spontaneous and experimentally induced C. renale infections in animals are frequently associated with alkaline urine, although this may be reflective of post infection bacterial hydrolysis of urea and production of ammonia rather than preexisting alkaluria.5,8,14

In this case, the histopathologic findings of necrotizing and hemorrhagic cystitis, and the microbial culture results from the contents of the urinary bladder support the underlying cause of death as complications from infection by non-diphtheritic coryneform bacteria. The signalment, clinical history, pathological findings and microbial culture results in this case of necrohemorrhagic cystitis show similarities to spontaneous and experimentally induced corynebacterial urinary tract disease observed in several animal species. The perineal bleeding was presumed to be normal estrous bleeding, therefore, diagnosis and treatment were delayed in this case. Severe urinary tract infection due to corynebacteria should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for protracted perineal bleeding in macaques.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In sheep, ulcerative posthitis of wethers (also known as sheath rot or pizzle rot)9, is a disease that occurs due to the presence of a transmissible urea-hydrolyzing bacterium and the excretion of urine rich in urea.3 The lesions begin as an ulceration of the prepuce that may progress to destruction of the urethral process and ulceration of the glans penis.3 C. renale, Rhodococcus equi, and C. hofmanni have all been isolated from infections.3

In dogs and cats Corynebacterium urealyticum, a urease-producing bacteria, is associated with alkaline urine of pH > 8 and struvite and calcium phosphate precipitations that form encrustations along the bladder wall.1,11 Staphylococcus sp and some strains of Proteus mirabilis are more commonly associated with alkaline urine and struvite production in dogs, but do not produce the mucosal encrustations seen with C. urealyticum.1

Table of common pathogenic Corynebacteriae adapted from Jones et al.6 and Quinn et al.9

| Organism | Principle Species | Disease |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Human | Diptheria |

| C. renale (Type I) | Bovine | "Bacillary" pyelonephritis, ureteritis, cystitis, may be recovered from healthy individuals |

| C. cystitidis (Type II) | Bovine | Hemorrhagic cystitis and pyelonephritis |

| C. pilosum (Type III) | Bovine | Cystitis and pyelonephritis |

| C. pseudotuberculosis | Ovine and caprine | Caseous lymphadenitis, produces phospholipase D exotoxin |

| Equine | Ulcerative lymphangitis and pectoral abscesses | |

| C. bovis | Bovine | Mastitis (rare), found in teat canal of 20% of apparently healthy dairy cows |

| C. kutscheri | Rodents | Pseudotuberculosis |

| C. ulcerans | Non-human primates, and many other species | Bite wounds and abscesses |

References:

2. Elias S, Abbas B, El San-Ousi SM: The goat as a model for Corynebacterium renale pyelonephritis. Br Vet J 149:485-493, 1993

3. Foster RA, Ladds PW: Male genital system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 614-615. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

4. Hayashi A, Yanagawa R, Kida H: Adhesion of Corynebacterium renale and Corynebacterium pilosum to the epithelial cells of various parts of the bovine urinary tract from the renal pelvis to vulva. Vet Microbiol 10:287-292, 1985

5. Jerusik RJ, Solomon K, Chapman WL, Wooley RE: Experimental rat model for Corynebacterium renale-induced pyelonephritis. Infect Immun 18:828-832, 1977

6. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by bacteria. In: Veterinary Pathology, eds. Thomas CJ, Hunt RD, King NW, pp. 479-481. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Boston, MA, 1997

7. Lipsky BA, Goldberger AC, Tompkins LS, Plorde JJ: Infections caused by nondiphtheria corynebacteria. Rev Infect Dis 4:1220-1235, 1982

8. Maxie MG, Newman SJ: Urinary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 490-494. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

9. Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Cater ME, Donelly WJC, Leonard FC: Corynebacterium species. In: Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease, pp. 55-59. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, 2002

10. Rebhun WC, Dill SG, Perdrizet JA, Hatfield CE: Pyelonephritis in cows: 15 cases (1982-1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 194:953-955, 1989

11. Saulez MN, Cebra CK, Heidel JR, Walker RD, Singh R, Bird KE: Encrusted cystitis secondary to Corynebacterium matruchotii infection in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc 226:246-248, 2005

12. Shimono E, Yanagawa R: Experimental model of Corynebacterium renale pyelonephritis produced in mice. Infect Immun 16:263-267, 1977

13. Stevens EL, Twenhafel NA, MacLarty AM, Kreiselmeier: Corynebacterial necrohemorrhagic cystitis in two female macaques. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 46:65-69, 2007

14. Yeruham I, Elad D, Avidar Y, Goshen T: A herd level analysis of urinary tract infection in dairy cattle. Vet J 171:172-176, 2006