Signalment:

Six-week-old male English setter dog (

Canis familiars)Two of nine puppies in a litter of English setter dogs developed erythematous cutaneous lesions at the age

of 2 weeks. Oral amoxicillin was given twice daily. After a week, the 2 puppies developed full body crusts, scabs,

blistered footpads, and pustules on the lips and the eyelids. The puppies were still in a good body condition and

nursing well. Other puppies in the litter were apparently healthy and doing well. Treatment was switched to

cefadroxil antibiotic with low-dose prednisone added into the suspension. At 4 weeks of age, a total of 4 puppies

were affected. Cefadroxil and prednisone were given to all 4 puppies with daily antimicrobial shampoos. The lesions

worsened irrespective of treatment with anthelmintic, antibiotics, anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory drugs. There

was some response to daily dosing of dexamethasone. Two severely affected puppies were hospitalized for more

intensive care and diagnostic evaluation. Full thickness skin biopsy was taken from one of the puppies. Given the

poor prognosis due to severity of the lesions and deteriorating health status, the 2 puppies were euthanized after 2

weeks of hospitalization (8 weeks of age) and necropsied.

Gross Description:

Grossly, there were extensive skin erythema with alopecia on the face, body, and extremities.

The tongues and oral mucosae were multifocally eroded and ulcerated.

Histopathologic Description:

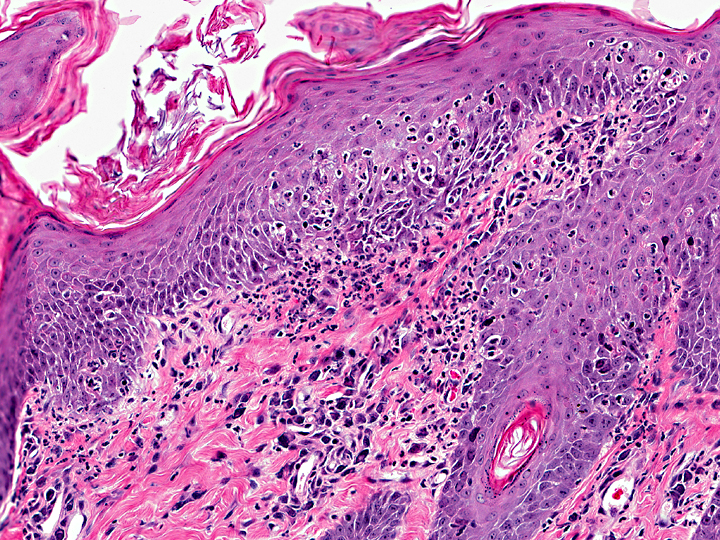

The epidermis of skin on the body, lips (mucocutaneous junction),

ears, and footpads, from both puppies was mild to moderately hyperkeratotic (parakeratotic), irregularly acanthotic,

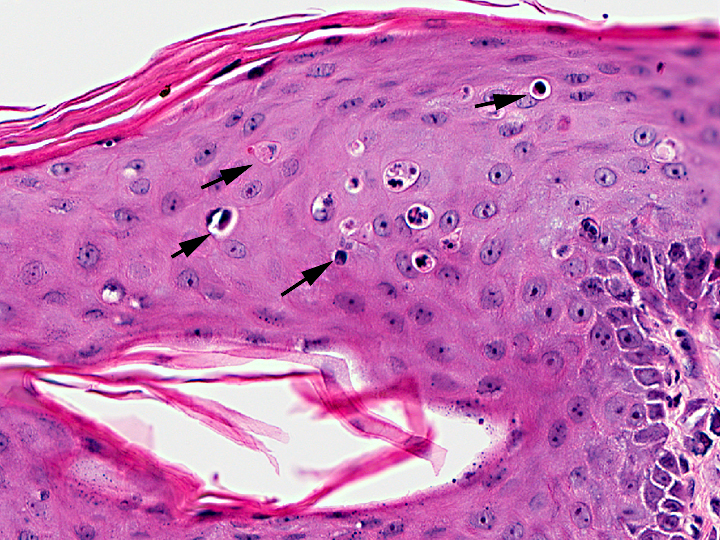

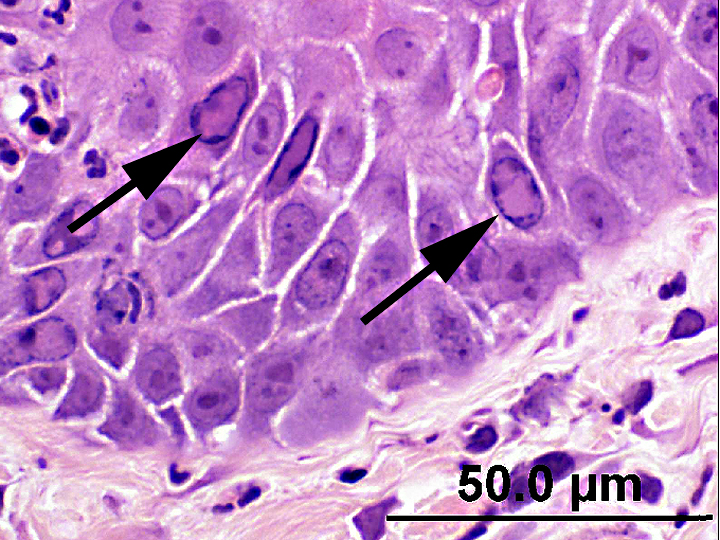

multifocally necrotic, and occasionally covered with serocellular crusts. In all layers of the epidermis, there was

scattered individual keratinocyte apoptosis with lymphocyte satellitosis (varies from slide to slide). The individual

cell apoptosis occasionally extended to the infundibular and upper sections of the hair follicles and associated

sebaceous glands. Few basophilic to amphophilic intranuclear inclusions were present in the apoptotic basal cells

and the overlying cells of stratum spinosum. Similar intranuclear inclusions were present in a few mast cells in the

papillary dermis, the mucosal cells of the tongue, the small intestine crypt enterocytes, and the myocardiocytes of

the heart in both puppies and in the mucosal cells of the oropharynx overlying the tonsil and in the epithelial cells of

the esophageal glands in one of the puppies. The microscopic findings in the other tissues besides skin were typical

of parvovirus infection. The findings in the other examined tissues were unremarkable.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Epidermitis, and folliculitis, necrotizing, subacute with parakeratosis and

intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions.

Lab Results:

Skin scrapings were negative for mites. Heavy growths of

Staphylococcus intermedius and beta

Streptococcus sp.

Group C and moderate

Rhizopus sp. were obtained from culture on hair and scab. Tissues from the tongue, lymph

node, spleen, skin, and small intestine from both euthanized puppies were positive for Canine parvovirus-2 (CPV-2)

and negative for Canine distemper virus (CDV) and Canid herpesvirus 1 by fluorescent antibody test (FAT).

Negative-staining electron microscopy detected parvovirus particles in the intestinal contents. The skin and small

intestine were positive for CPV-2b and negative for CDV by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The mucocutaneous

junctions and small intestines stained positive for CPV by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Condition:

Erythema multiforme

Contributor Comment:

The gross and microscopic lesions are consistent with erythema multiforme (EM).

Erythema multiforme is a cutaneous reaction of multifocal etiology seen uncommonly in dogs and rarely in cats.(3) In

dogs, EM is most commonly idiopathic or reported in association with administration of antibiotics, anthelmintics

and anti-inflammatory drugs, infections such as staphylococcal dermatitis, and folliculitis, and pseudomonal otitis

externa, feed, and a commercial nutraceutical product.(4,6-8) It is also described in association with CPV-2 in a dog.1

A group of chronic and persistent idiopathic EM is seen in older dogs (old dog EM) without a history compatible

with known triggers. Lesions are more exudative and proliferative, and predominantly involve the face and ears.(3) In

human beings, most cases were associated with drug administration and infections such as Herpes virus and

Mycoplasma pneumoniae.(5)

Despite recognition of multiple etiologic and triggering causes, the pathogenesis of EM is not completely

understood.(6,7) It is believed to be a host-specific T-cell mediated hypersensitivity reaction in which the immune

response is directed against keratinocyte-associated antigens associated with the triggering causes.(3) In EM, cluster of

differentiation (CD)44 was markedly up-regulated in keratinocytes and infiltrating cells and is involved in Tlymphocyte

activation and site-specific extravasation of lymphocytes into tissues.(7) Keratinocyte apoptosis is

probably produced by signals from intraepithelial CD8+ T lymphocytes.(8) Lymphocytes bind to the antigenically

altered keratinocytes and trigger cell death via apoptosis. Keratinocyte apoptosis is principally seen in the basal cell

layer in exfoliative cutaneous lupus erythematosus of the German shorthaired pointer dog, discoid lupus

erythematous, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Keratinocyte apoptosis in EM, however, is seen at all levels of the

epidermis.(3)

Erythema multiforme occurs in 2 forms that may overlap one another and to toxic epidermal necrolysis. Erythema

multiforme minor is characterized chiefly by an acute onset of cutaneous erythematous macules and papules. In EM

major (Stevens-Johnson syndrome), widespread mucosal lesions, extensive necrotizing and vesiculous skin lesions,

and signs of systemic illness such as pain, lethargy, and pyrexia are present.2 Based on this, the EM seen in the

current cases was classified as EM major.

Because of the diversity of triggering factors associated with EM, recognition of the underlying cause for each

individual case is important to propose the best treatment regimen. Age or sex predilection is not documented in

dogs and cats. Extensive studies and documentation are needed to determine breed predilection to EM in dogs.

Canine parvovirus infection was confirmed in several tissues and organs from the puppies by FAT, PCR, IHC, and

electron microscopy. The EM observed in this litter of English setters was associated with systemic CPV-2b

infection involving various tissues and organs.

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Keratinocyte necrosis, multifocal, moderate, with neutrophilic epidermitis and

folliculitis, marked perakeratosis, pustule formation, and viral intranuclear inclusion bodies.

Conference Comment:

Conference participants debated that the multifocal single-cell death in the epidermal

keratinocytes may be the result of the cytopathic effect of canine parvovirus, and not an indication of erythema

multiforme (EM). Consideration is also given to toxic shock syndrome (TSS), in which early lesions resemble EM,

although apoptotic keratinocytes are typically surrounded by neutrophils possibly due to the presence of bacterial

toxins. Although the cause of skin lesions associated with TSS has not been determined, superantigen exotoxins

which stimulate lymphocytes to release cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha may play a role(2).

The puppies in this case started showing clinical signs when only 2 weeks old. Participants did not expect such

young puppies to have developed an immune response directed against their own keratinocytes at such an early age.

Also, conference participants felt that the keratinocyte satellitosis was predominantly neutrophilic and not

lymphocytic. Additional features of EM that were not evident in our slide include a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate

obscuring the dermoepidermal junction and around superficial blood vessels (interface dermatitis), subepidermal

clefting and vesicle formation along the basement membrane, vacuolation of the basement membrane zone

(hydropic degeneration), pigmentary incontinence,and, less commonly, severe dermal edema with vertical

orientation of dermal collagen (gossamer collagen)(2, 3).

The pathogenesis of EM is not fully understood, but is thought to be a host-specific T cell-mediated hypersensitivity

reaction with a cellular immune response directed against various keratinocyte-associated antigens, including those

associated with drugs, infections (viral, fungal, bacterial), neoplasia, various chemical contactants, foods and

connective tissue disease. CD8+ T lymphocytes bind to antigenically altered keratinocytes (ICAM-1, MHC II,

CD1a, and CD44 expression is upregulated) and trigger cell death via apoptosis. Apoptotic keratinocytes coalesce,

leading to erosion, ulceration or hyperkeratosis. Studies support a combined type III and type IV immune reaction(2,3).

References:

1. Favrot C, Olivry T, Dunston SM, et al.: Parvovirus infection of keratinocytes as a cause of canine erythema multiforme.Â

Vet Pathol 37:647649, 2000.

2. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich, PM: The skin and appendages. In:

Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers pathology of domestic animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. I, p. 656-7, 686. Elsevier Saunders, New York, NY, 2007.

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EM, Affolter VK:

Skin disease of dogs and cats: clinical and histopathologic diagnosis, 2nd ed., pp. 5268, 75-8. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, UK, 2005.

4. Itoh T, Kojimoto A, Mikawa M, et al.: Erythema multiforme possibly triggered by food substances in a dog.Â

J Vet Med Sci 68:869871, 2006.

5. L+�-�aut+�-�-Labr+�-�ze C, Lamireau T, Chawki D, et al.: Diagnosis, classification and management of erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.Â

Arch Dis Child 83:347352, 2000.

6. Scott DW: Erythema multiforme in a dog caused by a commercial nutraceutical product.Â

J Vet Clin Sci 1:1621, 2008.

7. Scott DW, Miller WH: Erythema multiforme in dogs and cats: literature review and case material from the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (198896).Â

Vet Dermatol 10:297309, 1999.

8. Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE: Immune mediated disorders, erythema multiforme. In:

Muller and Kirks small animal dermatology, 6th ed., pp. 729740. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2001.