Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 8

October 25th, 2017

CASE II: N450-14 (JPC 4101759).

Signalment: 16-year-old, female, spayed, domestic crossbred, Felis catus, feline.

History: The cat had polyuria, polydipsia, anorexia, severe dyspnea, lethargy and progressive weight loss. In light of the clinical signs, a diagnosis of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus was suspected. The cat was hospitalized and treated to correct the fluid deficit and the increased electrolyte levels and received intramuscular insulin treatment (0.2 IU/ kg q24h). On the 10th day of hospitalization, after the acute onset of severe dyspnea, the cat died.

Gross Pathology: The lungs were swollen and heavy with a firm elastic consistency and were severely congested and slightly hemorrhagic. At the entrance to the right and left main bronchi there was a large quantity of friable, black material, interspersed with yellow foci that obstructed the bronchial lumen.

Laboratory results: Anaemia (hematocrit 21%, reference range [RR] 24-45%), leucopenia (4.0 x 109 /l; RR 5.0-19.5 109 /l), neutropenia (1.07x109 /l; RR 2.5-12.5 109 /l) and increased fructosamine (533.7 µmol/l; RR 219-247 µmol/l) and glucose (46.0 mmol/l; RR 4.05-7.43 mmol/l) levels were found. Urinalysis showed a moderate level of protein and a high level of glucose, with a specific gravity of 1.018 (RR >1.035). An ultrasound examination revealed a diffuse increase in the size and echogenicity of the liver and pancreas, likely resulting from hepatic lipidosis secondary to diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis. Sections of the lymph nodes and bone marrow underwent immunohistochemical evaluation for detection of feline immunodeficiency virus, feline calicivirus, and feline leukaemia virus (FeLV). No viral antigen was observed in these tissues.

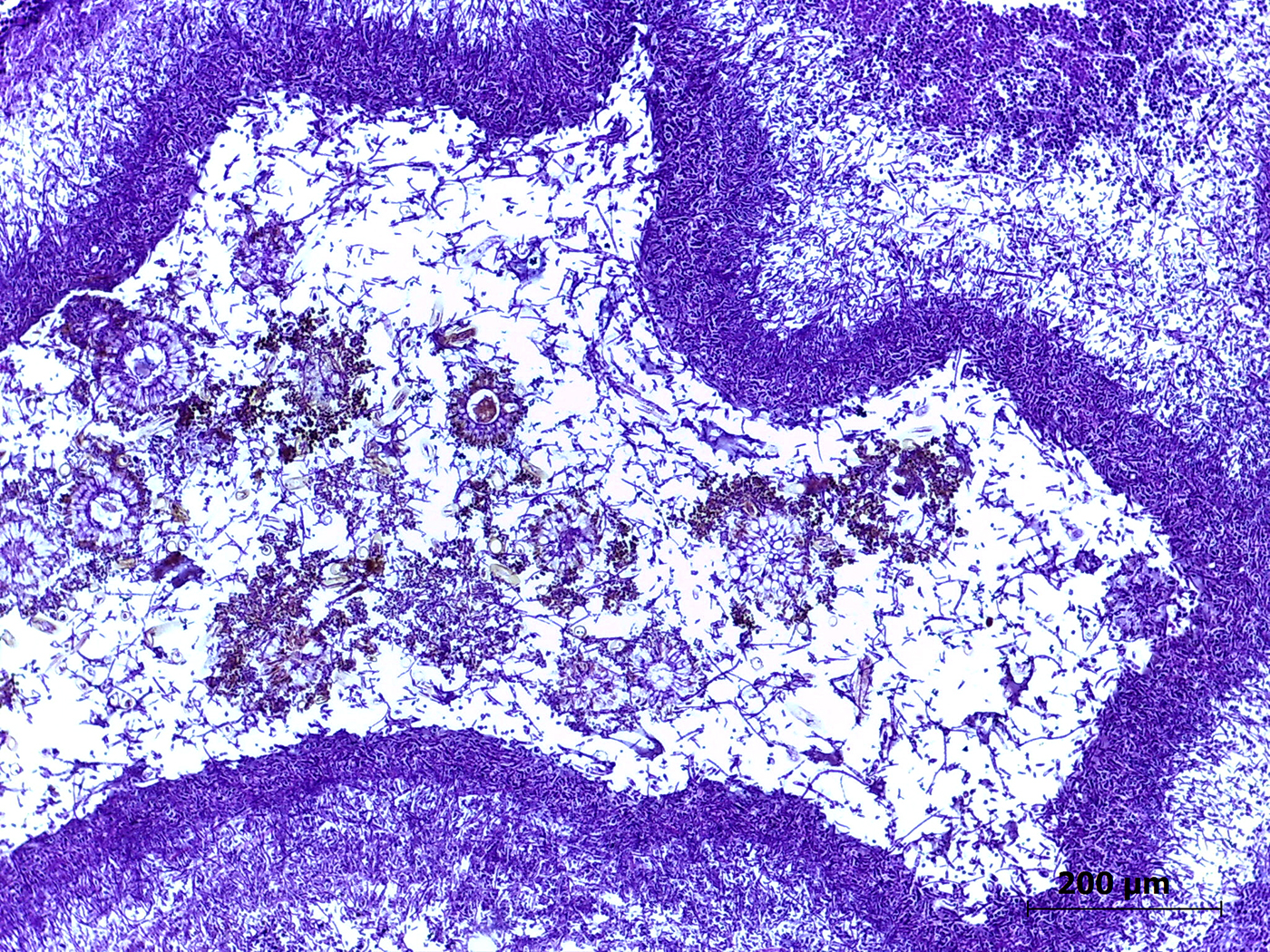

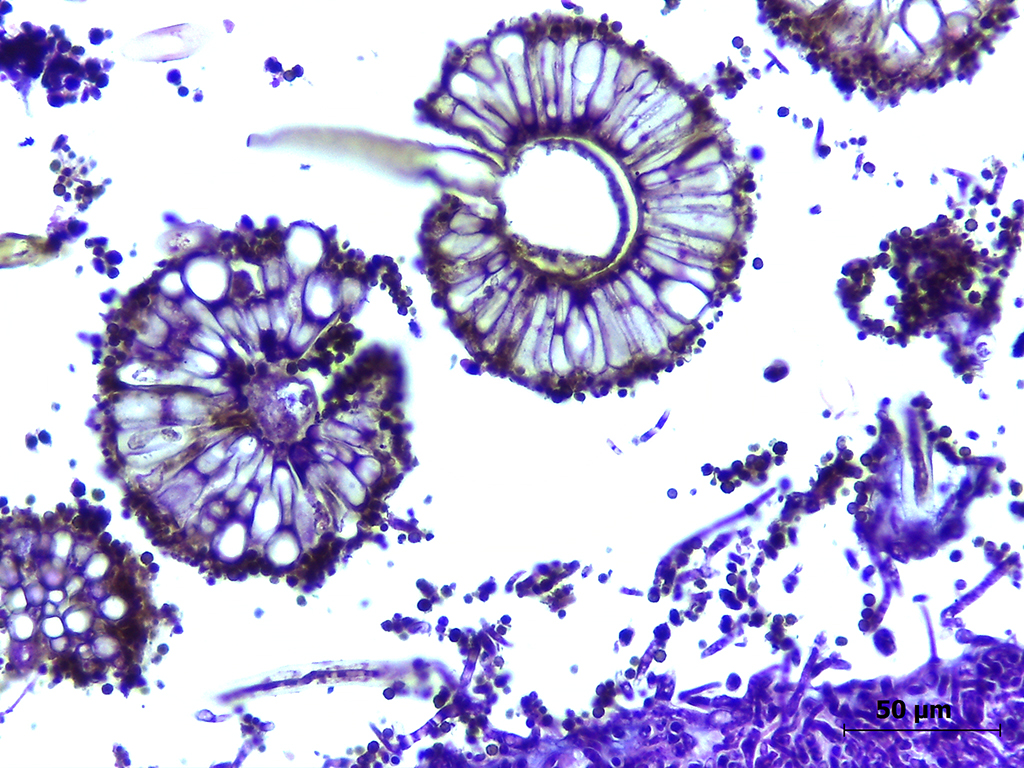

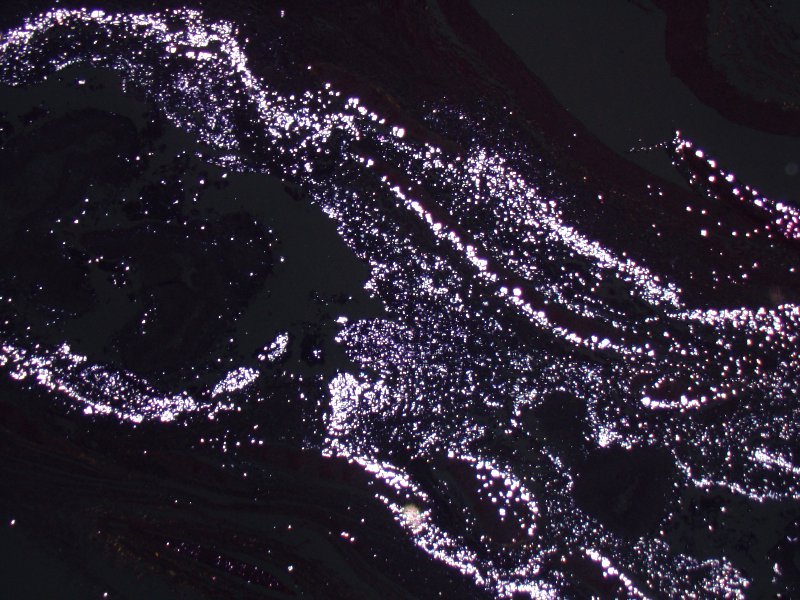

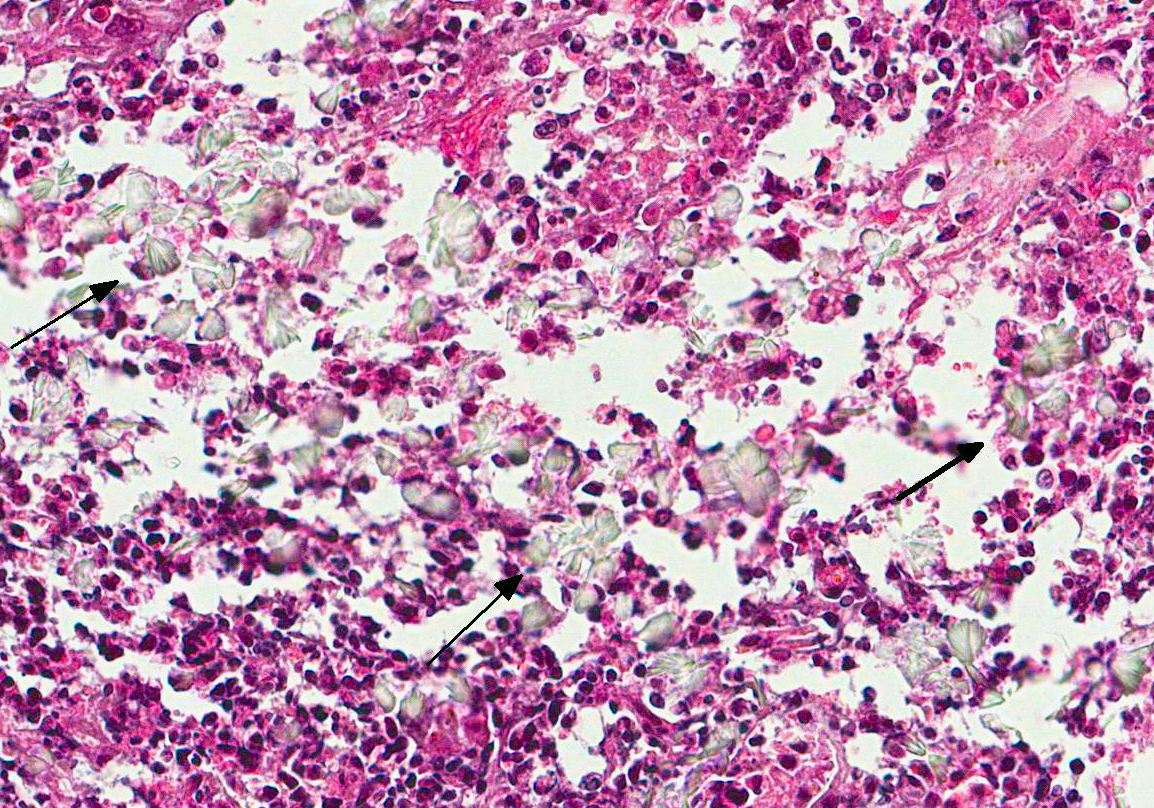

Microscopic Description: Lung: The pulmonary parenchyma and bronchial lumen revealed numerous septated, acute-angled or dichotomous branching hyphae (3-4 mm diameter). In addition, biseriate conidial heads with brown phialides and metulae, encompassing the entire surface, as well as smooth-walled, hyaline or darkened conidiophores, were found. The metulae developed in a double series and produced dark brown to black globose to subglobose conidia with rough walls (3-4 mm diameter). Septate hyphae occupied numerous air spaces and infiltrated the alveolar septa. An intense infiltrate that consisted predominantly of neutrophils and macrophages with fibrin deposition, associated with necrosis of the bronchial epithelium, and thrombosis was also observed. A methenamine silver stain was performed on the lung sections to highlight the fungi. Sections of the pulmonary parenchyma and bronchi were viewed under polarized light and revealed a high number of birefringent crystals with radiating spokes, consistent with calcium oxalate. No other tissue had evidence of fungal infection.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Lung: Bronchopneumonia, pyogranulomatous necrotizing, chronic-active, multifocal and extensive, severe, with intralesional fungi showing conidial heads and dichotomous branching hyphae of Aspergillus section Nigri and oxalate crystals.

Contributors Comment: There was a second cat with similar signs which also had diabetes and that had been sent, after its death, to necropsy. Fungal isolation was performed (only in the second case) by seeding samples and arranging tissue fragments in Sabourauds agar and malt agar. Fungal disease was not suspected in the first cat and unfortunately, no samples were collected for culture. The cultures from the second cat were incubated with chloramphenicol at 37ºC for 7 days for the isolation of Aspergillus spp. Identification of the fungal genus and section was performed by observing both the gross and the microscopical aspects of the colonies, which showed a fungus with an aerial black-stained mycelium and colorless reverse, identified as Aspergillus section Nigri.

Infections caused by Aspergillus spp. result in significant mortality in man and animals. Despite their ubiquitous distribution in indoor and outdoor environments, species in the Nigri section are not the most frequent cause of aspergillosis.8 Compared with species in the Fumigati section, species in the Nigri section have larger conidia, which allow easy uptake by the host mucociliary system and alveolar macrophages. The conidia of Aspergillus spp. develop from mycelia under high oxygen tension or severe infection, and they are not usually observed in histological sections.1 Fungal pneumonia caused by A. niger has been identified in horses by fungal culture,3 in dogs by molecular analysis6 and in man by fungal culture;8 however, there have been no reports of A. niger-mediated pneumonia in cats.

A. niger is part of a complex that includes many species, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish other species phenotypically, except using molecular identification by polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.10 The finding of calcium oxalate crystals in affected tissue is not recognized commonly in domestic animals, although it has been reported in human cases and has been considered a classical feature of A. niger infection.7,8 Both calcium oxalate crystals and numerous conidia were observed in the lung tissues of both cats, confirming A. section Nigri as the etiological agent. Oxalic acid is toxic and can damage tissues and the surrounding blood vessels, which explain the associated inflammatory infiltrate, composed mostly of neutrophils. However, the presence of oxalate crystals is most likely to be compatible with chronic inflammation.

No breed or gender predisposition is apparent for invasive focal or

disseminated feline aspergillosis, and cats with sinonasal/sino-orbital aspergillosis

can be of any age.2 Additionally, systemic immunocompromise due to

co-morbidities (e.g. feline parvovirus, FeLV or feline infectious peritonitis

virus infection, or prolonged corticosteroid treatment), has been considered

supportive evidence of aspergillosis.2 In this report, diabetes

mellitus identified as a risk factor for the development of aspergillosis in

cats, may have triggered and/or favoured the development of fungal infection in

the lower respiratory tract.5 Previous reports in man indicate that

prolonged diabetes mellitus, prolonged exposure to fungi and old age can

predispose patients to mycosis because these patients provide a favourable

environment for the growth of Aspergillus

spp..11 All of these features are similar to those observed in

the present cases.

In man, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurs predominantly in

immunocompromised hosts; however, the number of cases has increased among

immunocompetent patients who have certain pulmonary abnormalities, such as lung

neoplasia, as occurred in the first of the present cases. Diabetes mellitus is

a metabolic disease that can trigger a series of systemic complications.

Furthermore, infections accompanied by high morbidity and mortality are common

in diabetic patients. Susceptibility to infection results from immune

dysfunction, including reduced cytokine production, immune cell function and

migration. Several studies have also indicated an association between secondary

toxic metabolites, aspergillosis and immunosuppression of the host.9

Invasive aspergillosis caused by A.

section Nigri is rare, and the cases

described here demonstrate the aggressive nature of species of this section and

the potential to cause opportunistic infection in immunocompromised cats. Based

on the gross and microscopical findings of fungal hyphae combined with calcium

oxalosis and mycological examination, the diagnosis of chronic invasive

pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus

section Nigri was confirmed in

two diabetic cats. Not all sections contain conidiophores, however all of them

have hypha within bronchial lumina.

JPC Diagnosis: Lung: Bronchitis, pyogranulomatous and necrotizing, severe, with bronchiectasis, numerous fungal hyphae, pigmented conidia, and calcium oxalate crystals, domestic shorthair, (Felis catus), feline.

Conference Comment: The conference moderator reviewed the typical gross appearance of these lesions and referred to them as aspergillomas or fungal balls.4 These lesions occur in areas of the respiratory tract with high oxygen tension (often in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, or large conducting airways where a high oxygen tension allows for mycelial growth and may result in dyspnea and death. In this case, there were contextual clues indicating chronic disease, specifically, loss of cartilaginous basophilia and collapse of the parenchyma at the periphery of the bronchus.

Aspergillus sp. rarely causes lung disease in domestic animals. Of note, Aspergillus fumigatus and A. flavus can cause chronic destructive bronchitis in German Shepherd dogs. The lesions generated are similar to this case: erosion of the epithelium, neutrophil infiltration, and granulation tissue formation in ulcerated airways. There are mild microscopic differences in the morphology of the fungus (mentioned above by the contributor). This condition is very severe locally, but there have been no reports of progression to invasive systemic aspergillosis in dogs.4

Setor de Patologia Veterinária

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

http://www.ufrgs.br/patologia/

References:

1. Anila KR, Somanathan T, Mathews A, Jayasree K. Fruiting bodies as Aspergillus: an unusual finding in histopathology. Lung India. 2013; 30: 357-359.

2. Barrs VR, Talbot JJ. Feline aspergillosis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2014; 44: 51-73.

3. Carrasco L, Tarradas MC, Gómez-Villamandos JC, Luque I, Arenas A, Méndez. Equine pulmonary mycosis due to Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus stolonifera. J Comp Pathol. 1997; 117: 191-199.

4. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 502.

5. Furrow E, Groman RP. Intranasal infusion of clotrimazole for the treatment of nasal aspergillosis in two cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009; 235: 1188-1193.

6. Kim SH, Yong HC, Yoon JH, Yoshioka N, Kano R, Hasegawa A. Aspergillus niger pulmonary infection in a dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2003; 65: 1139-1140.

7. Procop WG, Johnston WW. Diagnostic value of conidia associated with pulmonary oxalosis: evidence of an Aspergillus niger infection. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997; 17: 292-294.

8. Person AK, Chudgar SM, Norton BL, Tong BC, Stout JE. Aspergillus niger: an unusual cause of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Med Microbiol. 2010; 59: 834-838.

9. Tomee JF, Kauffman HF. Putative virulence factors of Aspergillus fumigatus. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000; 30: 476-484.

10. Varga J, Frisvad JC, Kocsubé B, Brankovics B, Tóth B, Szigeti G, Samson RA. New and revisited species in Aspergillus section Nigri. Stud Mycol. 2011; 69: 1-17.

11. Wijesuriya TM, Kottahachchi J, Gunasekara TD, Bulugahapitiya U, et al. Aspergillus species: an emerging pathogen in onychomycosis among diabetics. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 19: 811-816.