Signalment:

On presentation at the teaching hospital, the colt was depressed to obtunded. He continually attempted to lie down and exhibited severe discomfort regardless of analgesia administration. Mucous membranes were hyperemic and tacky, and the horse was tachypnic. Reduced borborygmi were ausculted in dorsal left quadrant, with excessive borborygmi in all other quadrants. Dried feces were pasted to the perianal area. Serum chemistry abnormalities included albumin 1.7 g/dL (reference: 2.7-4.2 g/dL), total protein 4.8 g/dL (reference 5.8-8.7 g/dL), neutrophils 17,313 /uL (reference: 2600-6800 /uL), fibrinogen 700 mg/dL (reference: 100-400 mg/dL).

Nasogastric intubation resulted in no net reflux. Cloudy fluid was obtained via abdominocentesis and characterized by 19,880 total nucleated cells (89% neutrophils) and a lactate of 5.5 mg/dL. Due to unrelenting pain, immediate surgery was recommended and preparations were begun, but euthanasia was ultimately selected due to financial concerns.

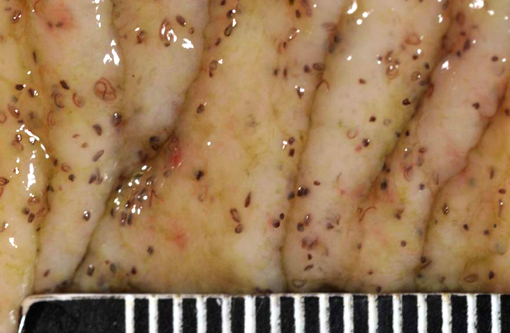

Gross Description:

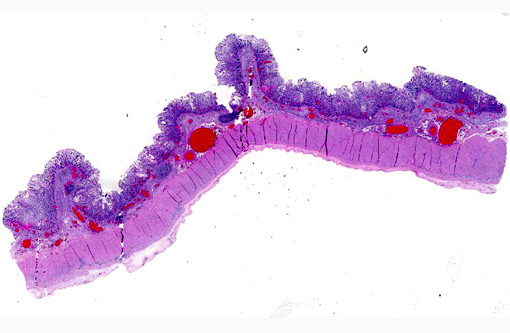

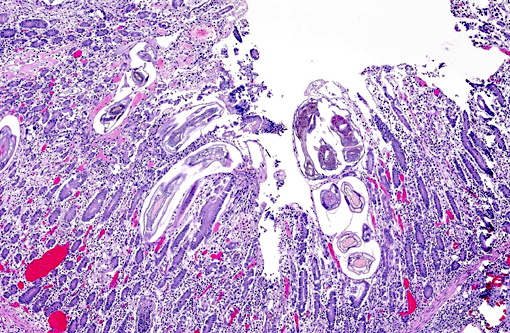

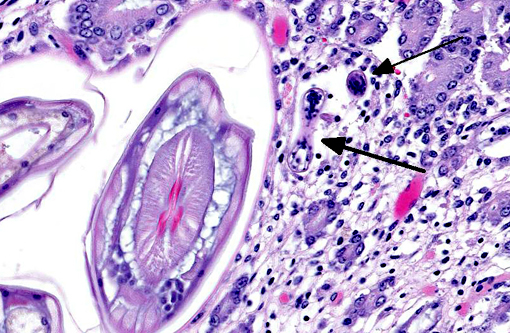

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Cecum: Apical cecal intussusception with acute infarction.

2. Large colon and cecum: Mucosal larval cyathostomiasis.

3. Peritoneum: Moderate peritoneal effusion.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

It is postulated that cyathostomes have become resistant to certain anthelmintic drugs.(4) A combination of lack of penetration of anthelmintics during the encysted stage along with current inconsistent deworming practices practiced by horse owners and managers has likely led to these new resistant populations, which in turn has led to an increase in incidence of infection over the last 10 years.(4,5) As a result, cyathostomes are considered the primary parasitic pathogen of horses.(6)

Cyathostomiasis has been associated with non-specific clinical signs of colic and chronic diarrhea, and more specifically with cecocecal intussusceptions.(6) Disrupted intestinal motility, which has been experimentally induced by infection with cyathostomes,(6) could contribute to both diarrhea and/or cecocecal intussusception. Given the large number of potential motility disorders in the horse, it is puzzling that cecocolic intussusception is commonly associated with only a limited number of etiologies. Some blood chemistry and hematology aberrations that have been associated with cyathostomiasis include neutrophilia and hypoalbuminemia.(6) Histopathological changes associated with cyathostome larvae infection of the colonic mucosa include a fibroblastic reaction to penetrating larvae, which results in distension and distortion of the glands as the larvae grow. Goblet cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy and a modest, predominantly lymphocytic, inflammatory infiltrate are associated with the encysted larvae.(6)

This colt had numerous clinical signs, hematologic changes, and post mortem findings characteristic of cyathostomiasis. The striking cecocolic intussusception was the probable source of colic and unrelenting pain that ultimately led to euthanasia. An additional sign supportive of intestinal dysmotility was pasting of feces in the perianal area, suggestive of diarrhea. Changes suggestive of cyathostomiasis in blood work parameters were found, including hypoalbuminemia and neutrophilia. Post mortem exam revealed abundant larvae encysted in the mucosa, with mucosal changes described above that are characteristic of cyathostomiasis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Adult small strongyles are essentially nonpathogenic; rather, it is the mass emergence of previously arrested larvae in a short period of time which causes clinical disease. The development of arrested larvae more often occurs from late winter to early summer, and the host and/or environmental factors which influence it are poorly understood.(1) Some evidence suggests the presence of luminal worms provide negative feedback to mucosal larvae,6 which may correlate with their emergence after anthelmintic treatment and elimination of adults, as likely occurred in this case. Interestingly, arrested development of larvae has been documented for periods extending over two years.(6)

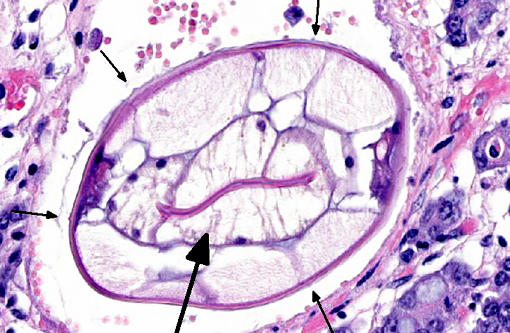

Histologic classification of nematodes is often possible when organisms are well preserved like in the current case. The characteristic large intestine with few multinucleated cells is readily identifiable and is indicative of one of three strongyle subgroups. Cyathostomes are part of the subgroup Trichostrongylus, and all are found with platymyarian musculature and longitudinal ridges along their external cuticle.(3) The ridges are faintly visible on some cross sections in this case as small and evenly-spaced. True strongyles also have platymyarian musculature, thick smooth cuticle and often vacuolated lateral chords. The third group, Metastrongylus, are the only strongyles with coelomyarian musculature.(3) Also important to speciation in this example is the presence of numerous organisms, as small strongyles often occur in large numbers.

Conference participants discussed the absence of fibrin thrombi within vessels in the affected area and how that relates to intestinal diseases of displacement such as an intussusception, which often do not cause endothelial damage. This is in contrast to infectious diseases such as Clostridium spp. or Salmonella spp., where fibrin thrombi are commonly observed.

References:

1. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:248-249.

2. Corning S. Equine cytahostomins: a review of biology, clinical significance and therapy. Parasites & Vectors (2009) 2 (Suppl 2):S1-6

3. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 1999:22.

4. Peregrine AS, McEwen B, Bienzle D, Koch TG, Weese JS. Larval cyathostominosis in horses in Ontario: An emerging disease? Can Vet J (2006) 47:80-82

5. Kaplan RM, Klei TR, Lyons ET, Lester G, Courtney CH, French DD, Tolliver SC, Vidyashankar AN, Zhao Y. Prevalence of anthelmintic resistant cyathostomes on horse farms. JAVMA, (2004) 225:903-910.

6. Love S, Murphy D, Mellor D. Pathogenicity of cyathostome infection. Vet Parasitol (1999) 85:113121.