Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 5

September 27th, 2017

CASE II: 16-180 (JPC 4102148).

Signalment: 6-month-old female Normande, Bos taurus, bovine.

History: Six of ten Normande heifers developed acute respiratory disease characterized by coughing and dyspnea. The animals had not been vaccinated against bovine respiratory disease complex and had not received antibiotic treatment recently. The heifers were grazing on a pasture of ryegrass and clover, with concentrate and silage supplementation.

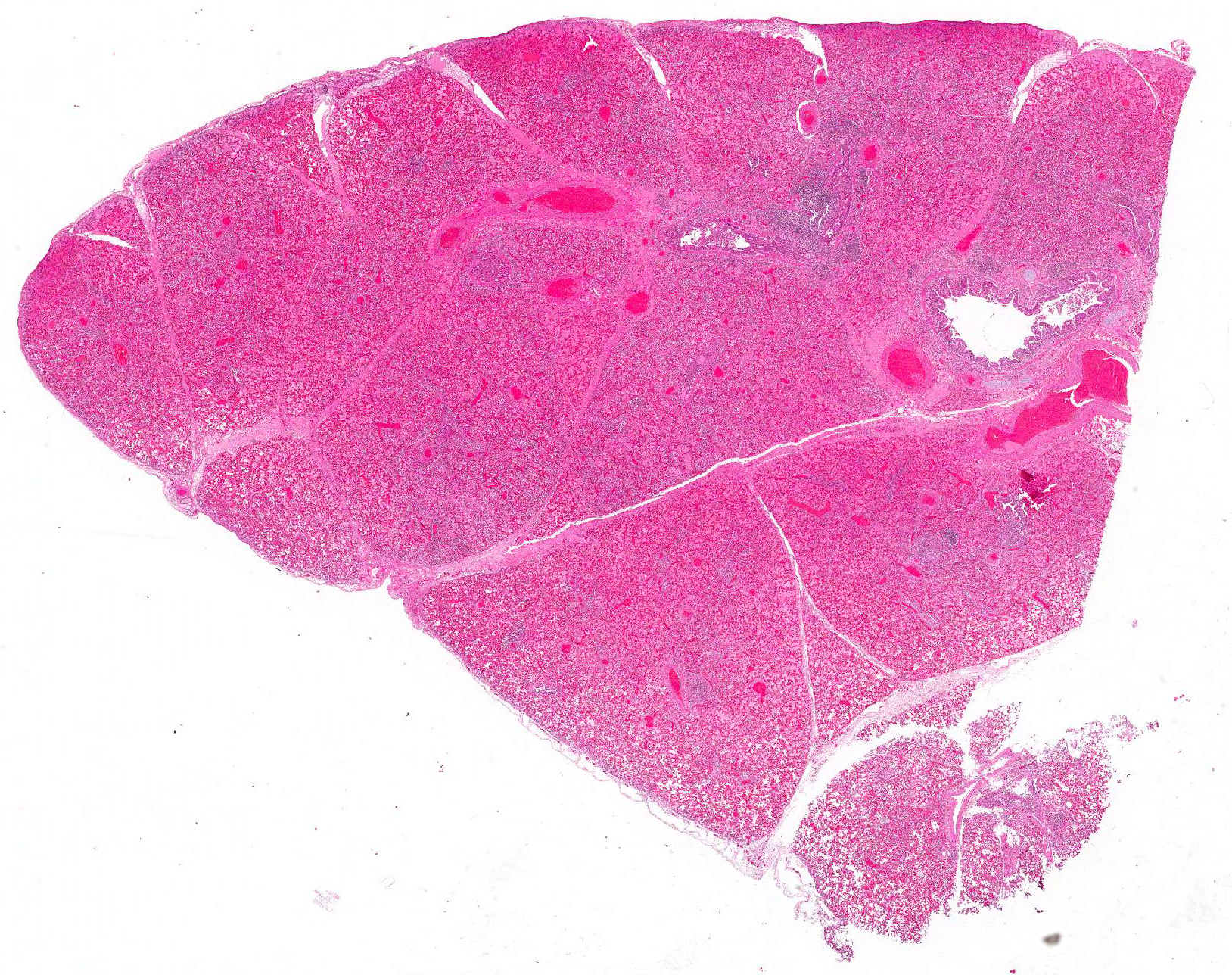

Gross Pathology: Bilaterally, the cranial lung lobes showed homogeneous dark red discoloration and firm consistency (consolidation) involving approximately 30% of the pulmonary parenchyma. The affected regions were well demarcated from the non-affected adjacent parenchyma. There was moderate amount of pink stable froth admixed with mucus in the thoracic portion of the trachea, accompanied by extensive petechiation in the tracheal mucosa.

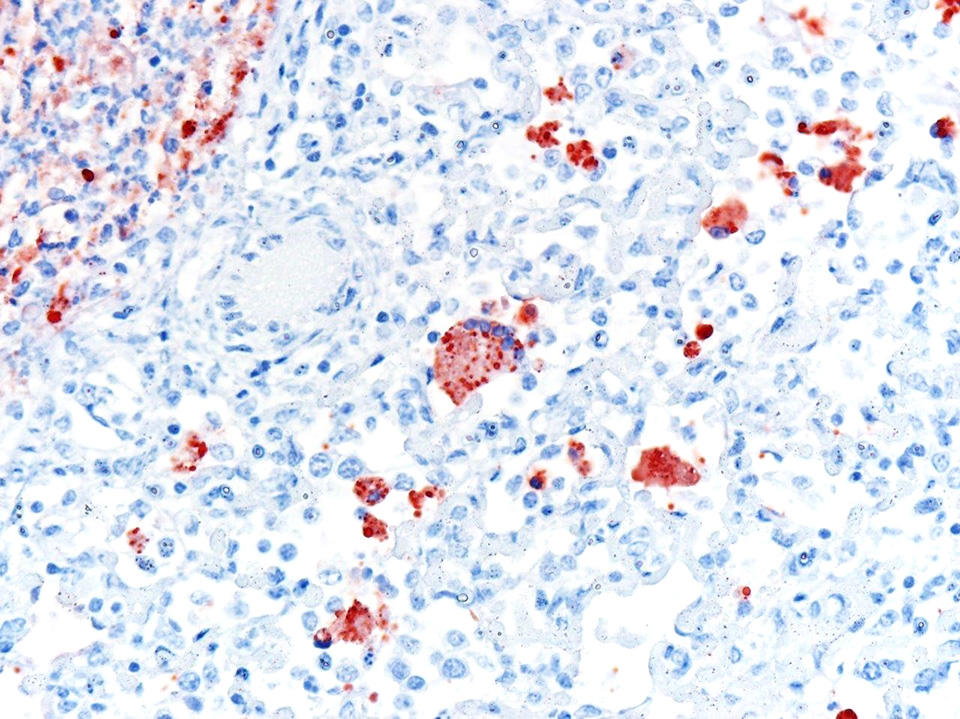

Laboratory results: No ancillary laboratory testing was done before the autopsy was performed. Immunohistochemistry was performed and was positive for bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) antigen within lung lesions. Additionally, PCR detected the viral genome in lung tissue.

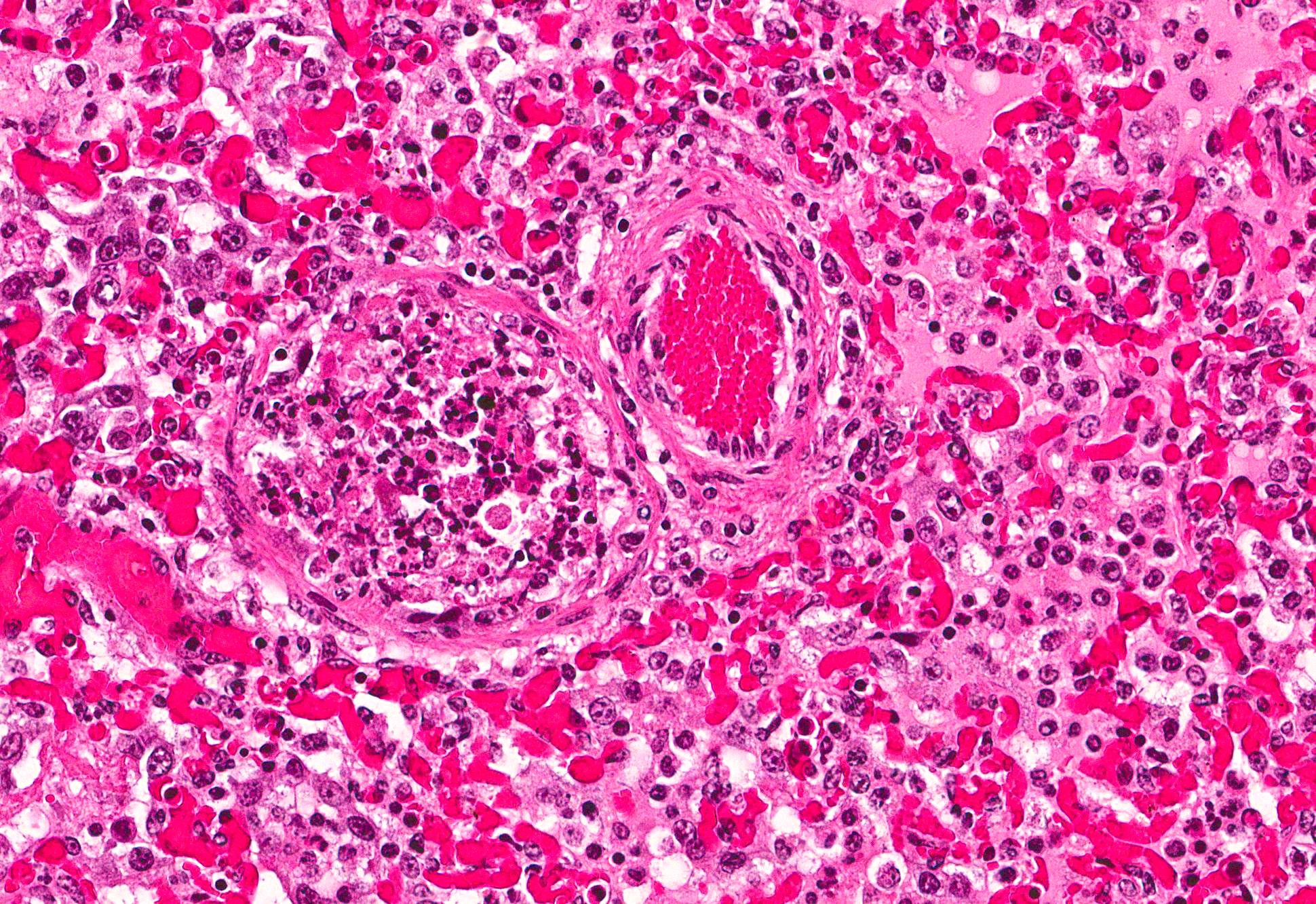

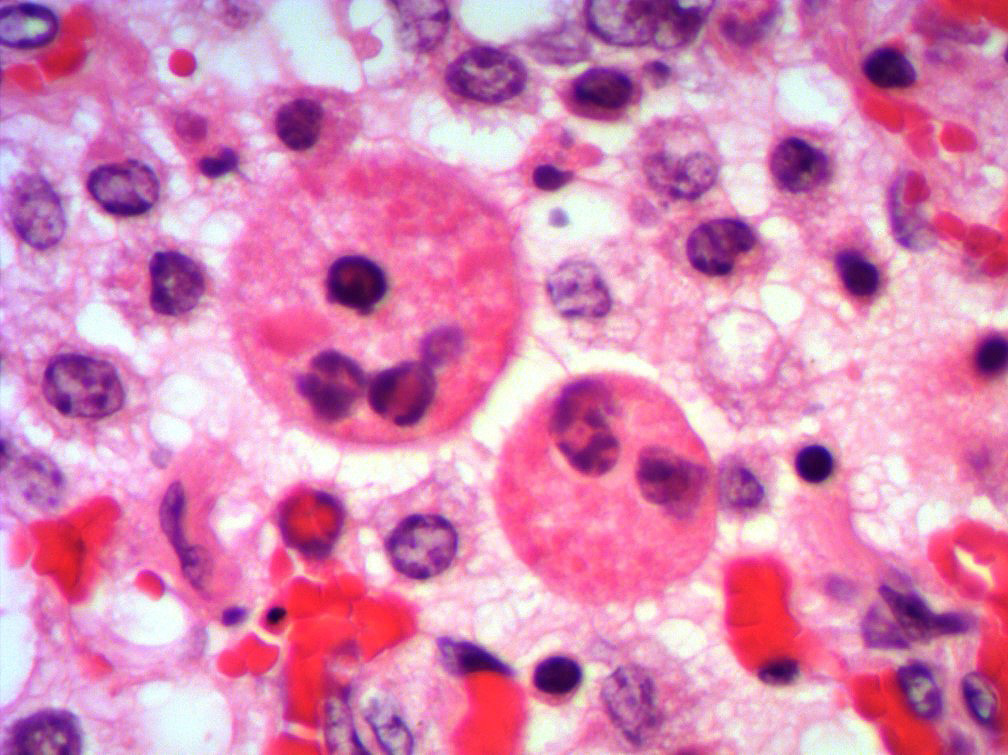

Microscopic Description: Lung: Multifocally, bronchioles are mildly ectatic and contain intraluminal necrotic cellular debris admixed with neutrophilic and fibrinous exudate that frequently occludes their lumen. Bronchiolar epithelial cells are either necrotic and sloughed, or markedly attenuated, with loss of apical cilia. In the alveolar spaces there is an amorphous homogeneous light eosinophilic material (edema), fibrin and moderate neutrophilic and multifocal histiocytic infiltrate (alveolar macrophages), with occasional and infrequent bi- or multinucleated syncytial cells, admixed with necrotic epithelial cells with hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei. Multiple, variably sized intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies are observed infrequently in some multinucleated syncytial cells. Some alveolar septae were lined by hypertrophied (type II) pneumocytes.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Bronchointerstitial pneumonia with necrotizing and neutrophilic bronchiolitis, type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, and rare multinucleated syncytial cells with intracytoplasmic viral eosinophilic inclusion bodies consistent with bovine respiratory syncytial virus, moderate, acute.

Condition: Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) pneumonia.

Contributors Comment: The bovine respiratory disease (BRD) complex is a multifactorial disease caused by several viruses and bacteria, including BRSV, parainfluenza 3 (PI3), bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1 or infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus, IBRV), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni and Mycoplasma bovis,2,4,6 among other possible causes.

BRSV (genus Pneumovirus, family Paramyxoviridae) is the most important viral etiological agent of the BRD complex, given its widespread distribution and high pathogenicity, 2 and is responsible for numerous outbreaks of respiratory disease worldwide.1,2,6 BRSV by itself causes an acute respiratory syndrome including dyspnea, tachypnea, coughing, anorexia, and hyperthermia, occasionally leading to death due to severe respiratory distress.6 Additionally, BRSV infection predisposes calves to secondary bacterial infections, such as M. haemolytica, P. multocida, and H. somni. It is estimated that the economic losses in cattle with BRD are in the range of US$23.23 and US$151.18 per animal, including deaths, decrease production and prevention and treatment costs.1 For detailed information on BRSV epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis, diagnosis, and immunology, please refer to the excellent review by Sacco et al. 2014.

In the case presented herein, the diagnosis of BRSV was made by intralesional detection of BRSV antigen by immunohistochemistry, and by detection of the viral genome by PCR in lung tissue. In cases of respiratory disease, the histologic lesions of bronchointerstitial pneumonia with necrotizing bronchiolitis and syncytial cells are highly suggestive of BRSV and should raise a suspicion for this agent. However, the observation of syncytial cells alone is not conclusive for the diagnosis, particularly if typical inclusion bodies are not observed upon histologic examination. PI3 infection may also produce syncytial cells and inclusion bodies similar to those produced by BRSV. Furthermore, fibrinous bronchopneumonia caused by several bacteria induces formation of macrophagic multinucleate giant cells morphologically similar to syncytial cells in the lumen of bronchioles and alveoli. Consequently, viral detection by PCR or IHC is necessary for the etiologic diagnosis of BRSV pneumonia.2 In this case, IBRV, PI3 and bacterial agents were ruled out in lung tissue by IHC, PCR and bacterial cultures, respectively.

In Uruguay, the distribution, frequency and economic impact of BRSV for the cattle industry are unknown. In a serologic study in 100 cattle from different regions of the country, 95% were positive to anti-BRSV antibodies by ELISA,3 which suggests that the agent has a wide geographic distribution. However, there are few reports of BRSV-associated pneumonia in cattle in this country.5

JPC Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, bronchointerstitial, necrotizing and fibrinosuppurative, diffuse, severe, with rare alveolar and bronchiolar multinucleated viral syncytia with intracytoplasmic viral inclusions, Normande, bovine.

Conference Comment: This is apparently a straightforward case of uncomplicated bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) in a young heifer. Uncomplicated cases are rare since BRSV impairs the mucociliary apparatus, predisposing affected animals to secondary bacterial infections.

Conference participants identified classic microscopic features of BRSV, centered on the bronchioloalveolar junction, including necrotizing bronchiolitis, alveolar edema and inflammation, and moderate numbers of viral syncytial cells within the bronchiolar and alveolar lumens containing eosinophilic intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies.

Attendees also discussed the possibility of bronchiolitis obliterans formation due to chronic bronchiolar damage. Bronchiolitis obliterans is a polypoid proliferation of fibrous connective tissue lined by attenuated epithelial cells that causes obstruction of airways, resulting in hypoxic vasoconstriction of the pulmonary parenchyma, pulmonary hypertension, and right heart failure.2

Bovine respiratory syncytial virus is common among beef and dairy herds in Europe and North America and is an important cause of acute outbreaks of respiratory disease and enzootic pneumonia in 2-week-old to 5-month-old calves.2 BRSV is spread via aerosol and targets the ciliated cells of the conductive system and alveolar type II pneumocytes of the gas exchange component of the respiratory system. The virus (like other Paramyxoviruses) attaches via heparin binding domains on envelope glycoprotein G, and enters the cell using envelope glycoprotein F, its fusion protein, which also induces the formation of syncytial cells. Viral syncytia allow interaction with and spread to adjacent unaffected cells. Once host cells are infected a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines is released, recruiting neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages to the lesion.

Experiments in tissue culture have revealed that the virus itself does not cause very much damage to respiratory epithelium. It has been presupposed that most of the damage is due to exuberant host defense mechanisms.7 Gross lesions associated with BRSV infection range from red, rubbery cranioventral lungs (atelectasis) to firm, heavy, edematous caudodorsal areas of lung that fail to collapse postmortem. However, there are frequent variations in the gross appearance for several reasons: (1) If calves die in respiratory distress, there is often marked subpleural and interlobular emphysema with bullae formation; and (2) Secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia can become so severe as to obscure more subtle viral lesions.2 The microscopic lesions noted above (necrotizing bronchiolitis with syncytial cells) are highly suggestive of BRSV; however, bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (BPIV-3) must also be considered.

Bovine parainfluenza virus 3 (BPIV-3) is also a member of the Paramyxoviridae family. Microscopic lesions can be identical to BRSV although there are usually fewer syncytial cells and the clinical course is typically less severe. Diagnosis requires virus isolation or detection of viral antigen by immunohistochemistry or nucleic acid by RT-PCR testing (as in this case). Unfortunately, definitive diagnosis is often problematic, as viral antigen can be cleared from the body long before the secondary bacterial pneumonia results in death of the animal.2

Animal Health Platform

National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA)

Uruguay

References:

1. Brodersen BW. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 2010. 26:323-333.

2. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer´s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 504, 539-546.

3. Costa M, García L, Yunus AS, Rockermann DD, Saml SK, Cristina J. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus: First serological evidence in Uruguay. Vet Res 2000. 31:241-246.

4. Griffin D, Chengappa MM, Kuskak J, McVey DS. Bacterial pathogens of the bovine respiratory disease complex. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 2010. 26:381-394

5. Rivero R, Sallis ESV, Callero JL, Luzardo S, Gianneechini R, Matto C, Adrien ML, Schild AL. Neumonía enzoótica asociado al virus respiratorio sincitial bovino (BRSV) en terneros en Uruguay. Veterinaria (Montevideo). 2013. 49:29-39.

6. Sacco RE, McGill JL, Pillatzki AE, Palmer MV, Ackermann MR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in cattle. Vet Pathol 2014. 51:427-436.

7. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 208-209.