Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 3

Sept 12, 2018

CASE IV: AFIP Canine 315010212_lungs (JPC 4067411-00).

Signalment: 1 year-old female Weimeraner dog, Canis lupis familiaris.

History: After undergoing anesthesia for laminectomy of T10 this dog failed to regain independent breathing and was euthanized during recovery.

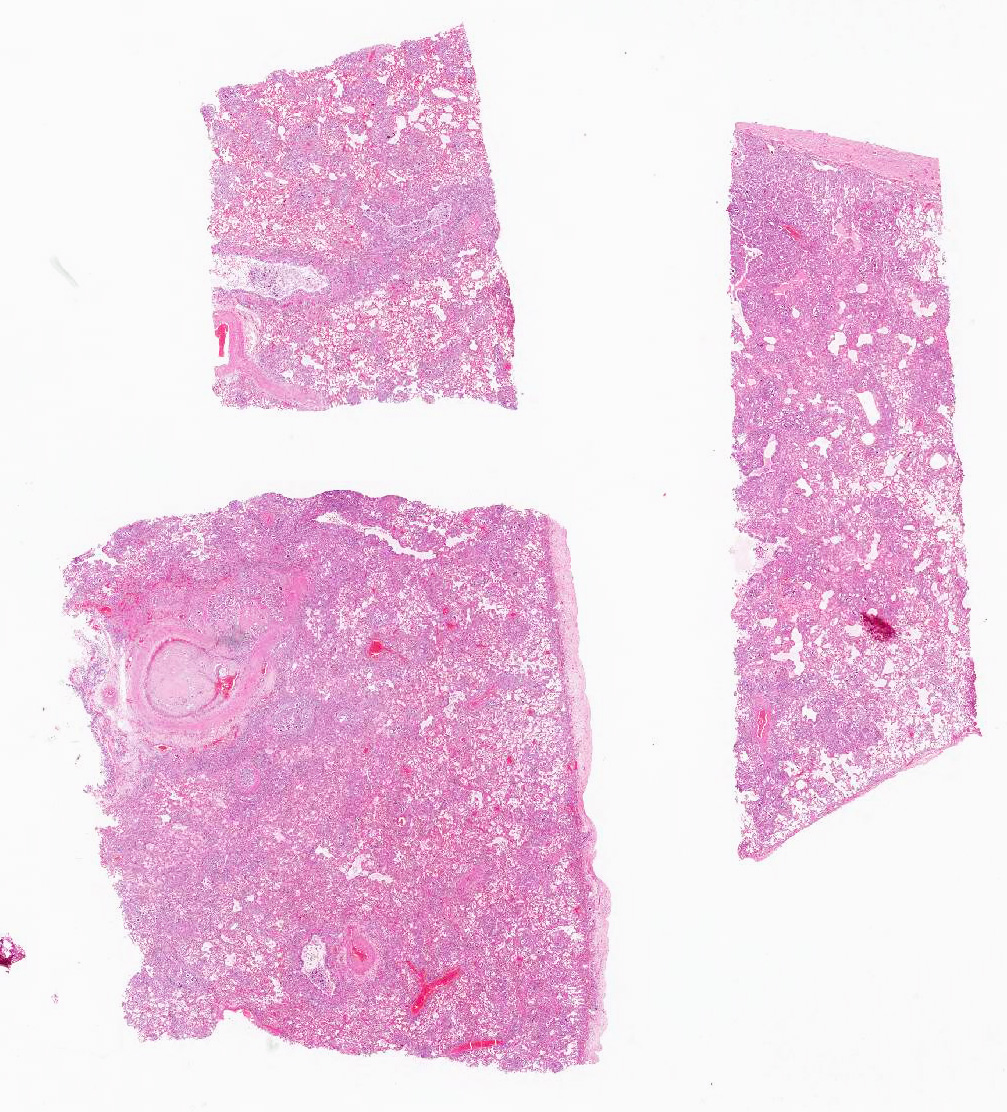

Gross Pathology: The lungs have a mottled appearance composed of small areas of hemorrhage intermixed with coalescing areas of pale grey to tan tissue with multifocally slightly raised whitish nodules of a few millimeters in diameter. Both lungs are markedly oedematous, have an increased consistency and are firm to touch. There is a small amount of fibrin on the pleura of the cranioventral lobes.

Laboratory results: None.

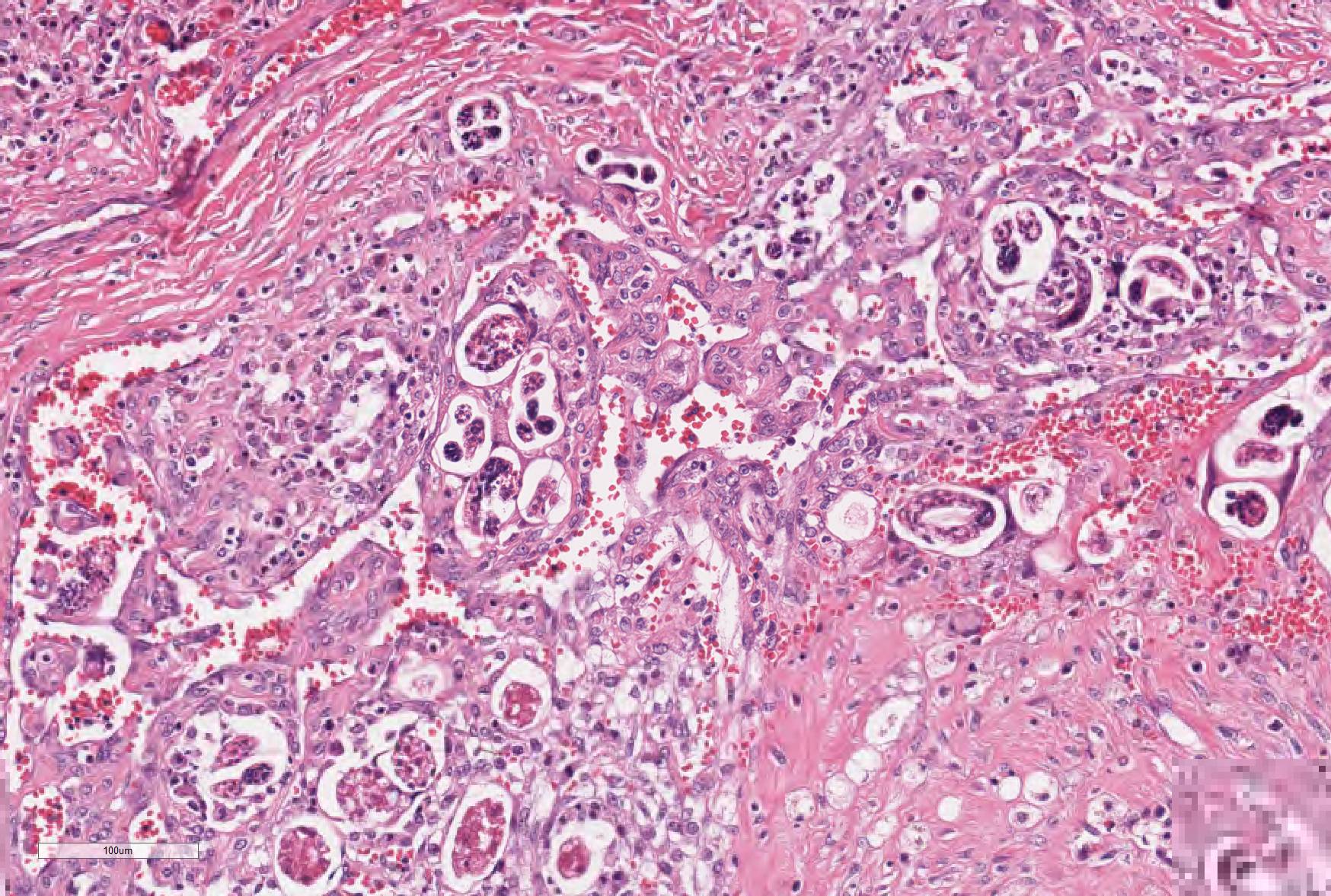

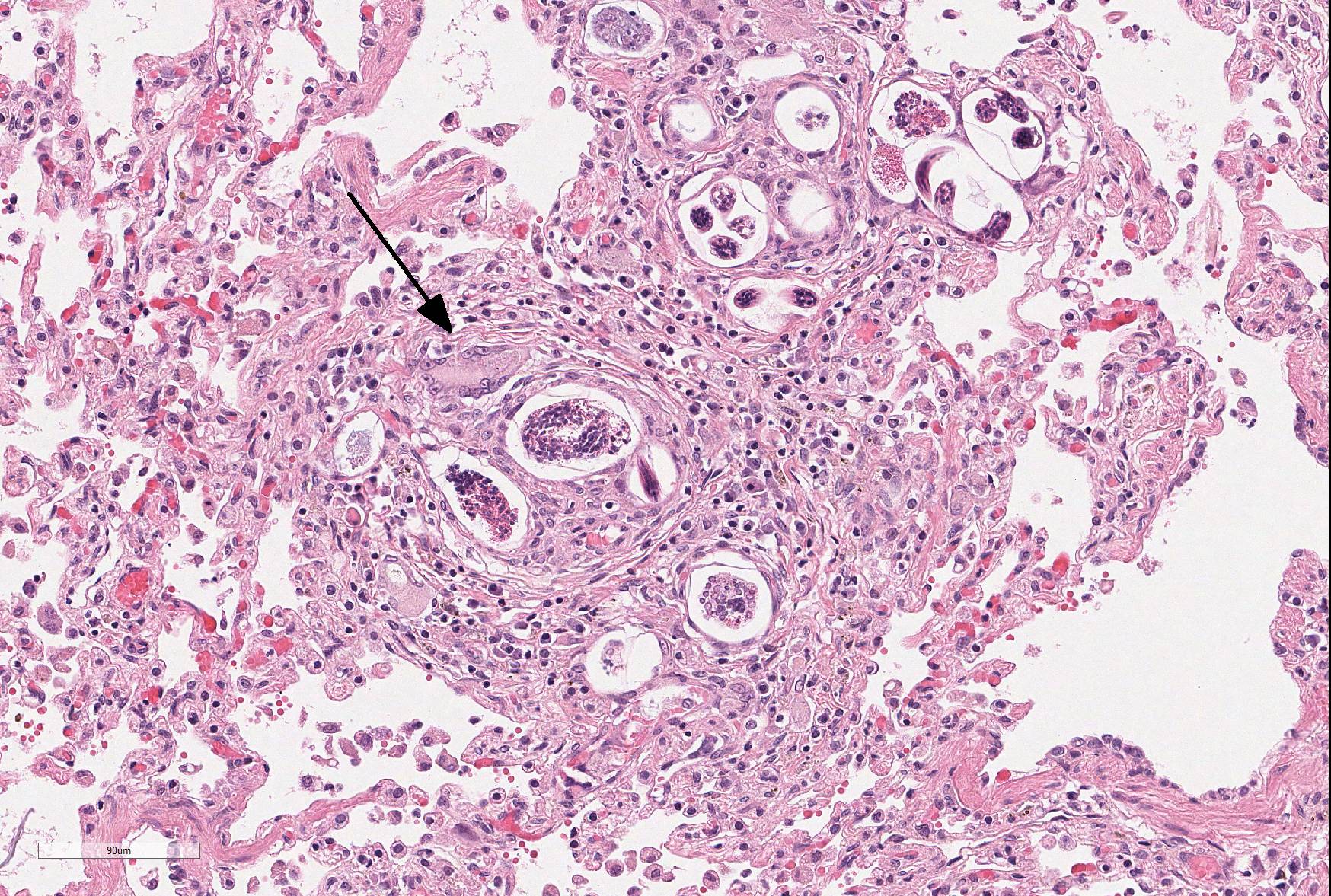

Microscopic Description: Lung: The normal architecture of the lung is severely distorted by the presence of a predominantly granulomatous interstitial infiltrate associated with the presence of numerous Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae and eggs.

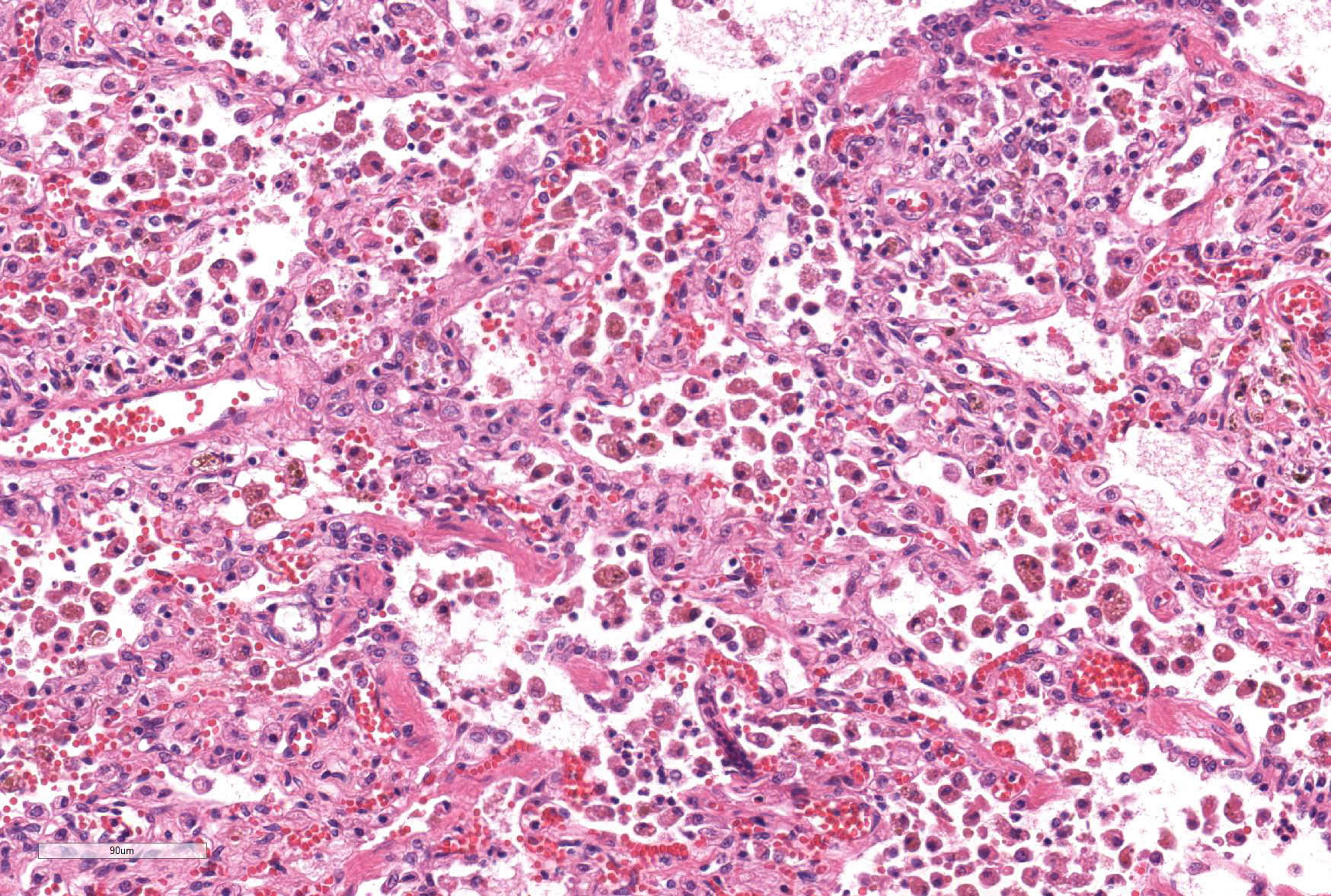

In both the alveolar interstitium and free within the alveolar spaces are moderate to large numbers of transverse or longitudinal sections of nematode larvae measuring approximately 20x80 µm and fewer multinuclear (embryonated) and uninuclear (non-embryonated) eggs, recognizable as approximately 60x90 µm, oval-shaped accumulations of coarsely granular eosinophilic material. These are typically surrounded by moderate numbers of extravascular erythrocytes, epithelioid macrophages (which occasionally show erythrophagy and contain cytoplasmic hemosiderin granules) and scattered multinucleated giant cells. The alveolar septa are often indistinct and are markedly expanded by moderate numbers of macrophages, fewer plasma cells and lymphocytes, and occasional eosinophils as well as moderate edema, and parasites. Alveoli are frequently lined by plump cuboidal epithelial cells (type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia).

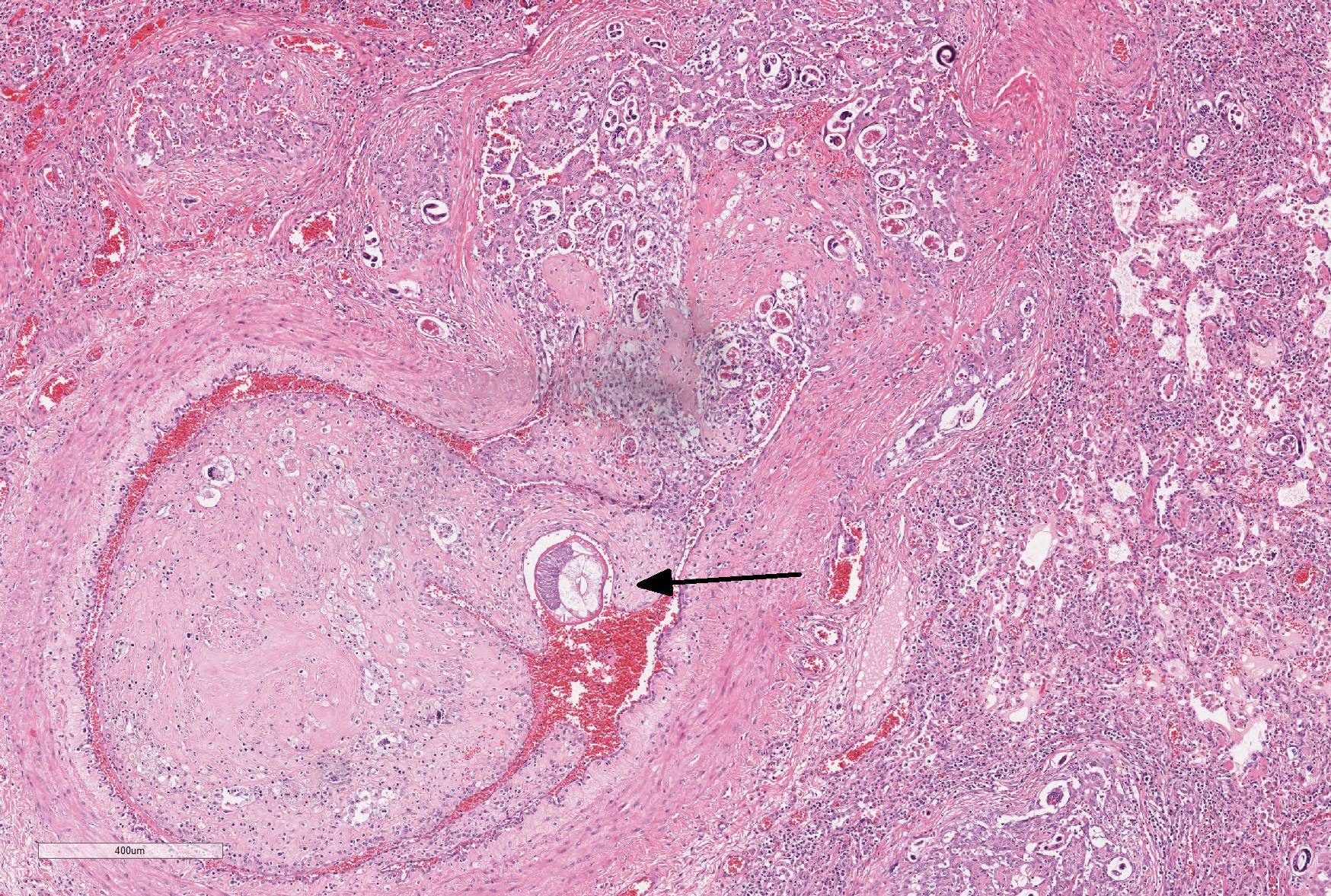

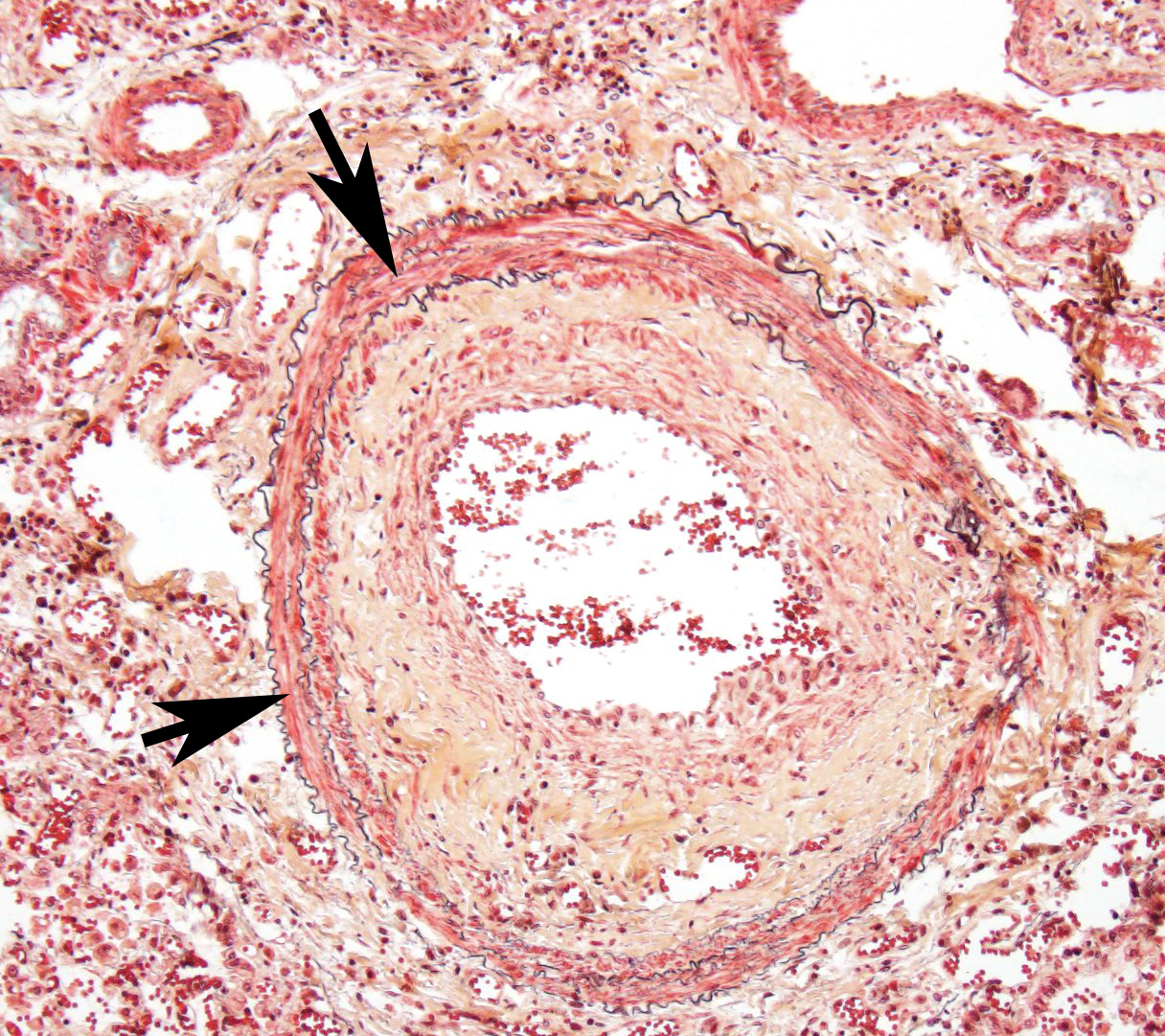

Throughout the section, there are mild to moderate vascular changes including moderate hypertrophy of the lamina media, separation of the collagen fibers of the tunica adventitia by fine reticular eosinophilic material (edema), and the presence of parasites within the vascular lumen. In the adventitia of some vessels, there are increased numbers of small-caliber blood vessels.

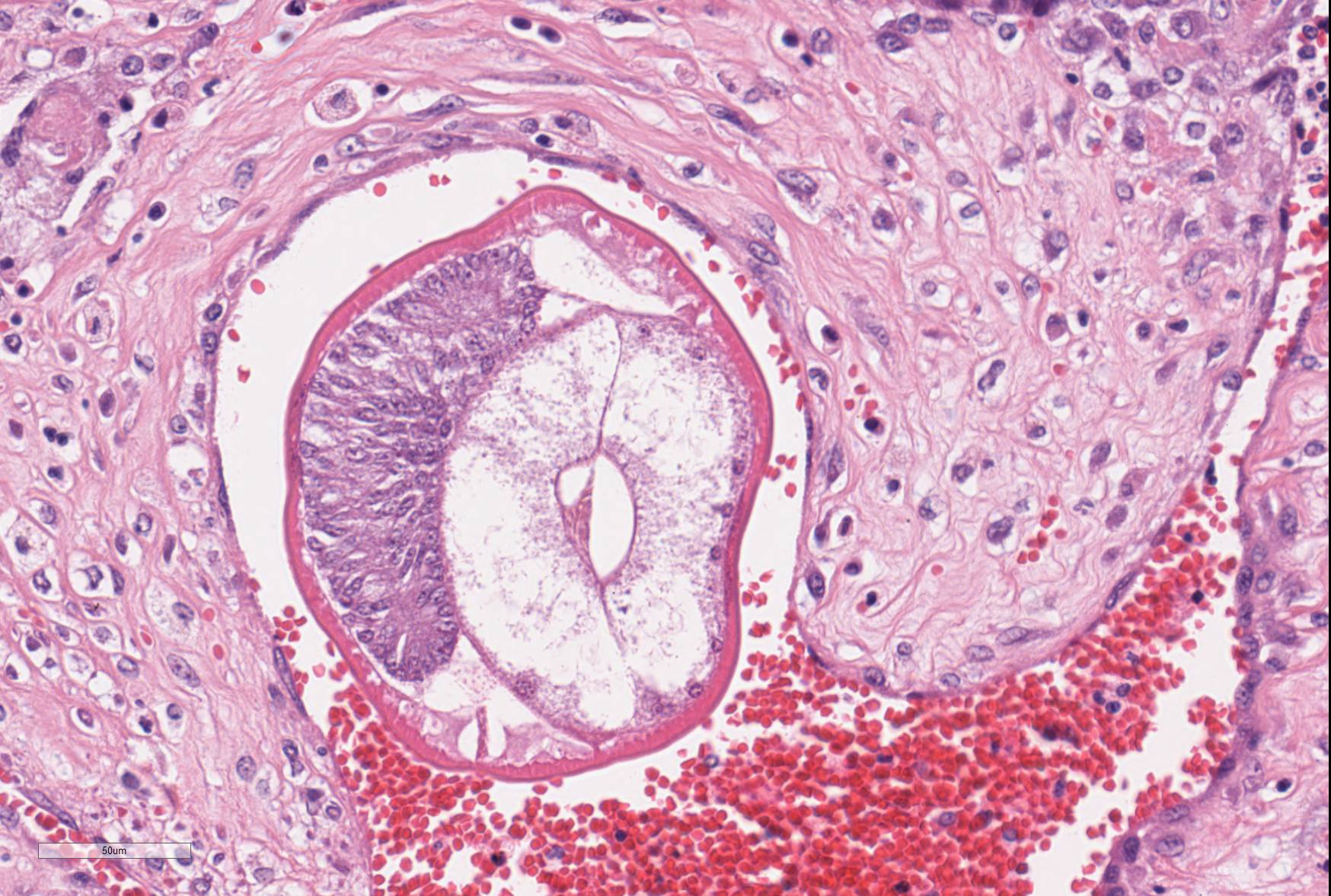

In some sections, adult nematodes are present within the lumen of large blood vessels; these are approximately 300µm in diameter and are characterized by a thin eosinophilic cuticle surrounding coelomyarian musculature and a pseudocoelom containing digestive and reproductive tracts. In some cases this is associated with partial occlusion of the lumen by an organizing thrombus composed of haphazardly arranged collagen bundles and fibroblasts, with endothelial cells forming small vascular channels (recanalisation) and scattered parasite eggs. Throughout the thrombotic material are moderate numbers of mixed inflammatory cells, predominantly plasma cells and macrophages. The lamina intima is markedly expanded by edema and moderate numbers of plasma cells and macrophages with fewer lymphocytes and occasional neutrophils. There is intimal hyperplasia characterized by the formation of multiple, endothelium-lined small, rounded, projections into the vessel lumen (proliferative endoarteritis).

Also in the less-severely affected areas, alveolar spaces and bronchiolar lumens contain moderate numbers of epithelioid macrophages, erythrocytes and protein-rich material. Bronchial epithelium shows mild hypertrophy and there are scattered intramucosal neutrophils.

The pleura is moderately expanded by mild fibrosis and edema and in some sections there are scattered groups of parasite eggs and larvae surrounded by macrophages, plasma cells and lymphocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Lung: Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing interstitial granulomatous pneumonia with Angiostrongylus vasorum in different stages of development, interarterial thrombosis and marked pleural fibrosis.

Contributor’s Comment: Angiostrongylus vasorum, or French heartworm, is endemic in the Americas, parts of Africa and some European countries but until the end of the last decade was not considered endemic in the Netherlands.5 The few cases reported before this time were typically seen in dogs which had been travelled outside of the country. Following the emergence of the disease in dogs which had never been outside the Netherlands, research was carried out to determine the prevalence of this parasite in Dutch foxes and intermediate hosts. Interestingly, concurrent to the increase in cases of A. vasorum seen in domestic dogs there has been an expansion of the range and population of foxes reported in the Netherlands. Combined with the wet Dutch environment that is conducive to the survival of the gastropod intermediate hosts, establishment of A. vasorum in the Netherlands is not surprising.5 Of particular importance is the finding that L3 or the infective stage can be released from the intermediate host in fresh water meaning that infection may occur not only by ingestion of slugs and snails but by drinking water from the many canals and ditches that are prominent features of the Dutch countryside. 5

There was no history available for this young dog which underwent surgery for suspected lymphoma of the spinal cord from which it did not recover. The severe parasitic pneumonia may explain the post-surgical failure to resume independent breathing.

The histological lesions in this case are typical of a chronic, patent infection with multiple stages of parasite present and organizing thrombosis seen in the pulmonary vessels. The adults inhabit the right ventricle and pulmonary arteries releasing eggs after a pre-patency period of 35-60 days.2 These are transported to the pulmonary capillaries from which L1 larvae hatch and penetrate into the alveolar spaces before being coughed up and excreted in the faeces. L1 are taken up by intermediate hosts (including snails, slugs and frogs) in which larval development continues to the infectious L3 stage and infection occurs in definitive hosts when these are ingested and mature larvae and young adult worms migrate via the circulatory system ultimately inhabiting the right ventricle. The presence of adult worms in the circulatory system is thought to activate both intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways resulting in intravascular consumptive coagulopathy and bleeding tendencies.4 This may explain the persistent bleeding at the that was noted incision site during the operation preceding the death of this dog.

Whilst infection with A. vasorum can cause a range of other clinical signs the majority of cases develop cardiorespiratory problems, typically culminating in heart failure.2,3 Other clinical presentations may reflect aberrant larval migration to organs such as the eye and brain.2,3,5

JPC Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, granulomatous, diffuse, severe, with proliferative endarteritis, thrombosis, and recanalization, and rare adult and numerous metastrongyle larvae and eggs.

Conference Comment:

Angiostrongylus vasorum, termed French heartworm because it was reported first in France in the 1800s1, is a metastrongyle nematode considered to be the most pathogenic lungworm of dogs. A. vasorum has a worldwide distribution and the infection seems to be increasing in recent decades. Red foxes are the natural definitive hosts and are important reservoirs of infection for domestic dogs, however, natural infection has also been reported in other species including wolves, coyotes, and Eurasian badgers.1

Adults reside in the pulmonary artery and right heart ventricle in canids. Clinical signs run a gamut from mild coughing and exercise intolerance to fatal cardiopulmonary disease which may manifest as sudden death.

- vasorum may cause right heart failure and extensive pulmonary lesions as a consequence of egg embolization. Prepatent lesions are mild with adult worms in the pulmonary arteries and a few 1-2 mm diameter, red, firm, multinodular to confluent areas of hemorrhage and edema at the lung periphery.2 Female adults have a “barber pole” appearance due to their intertwined red intestine and white ovaries. At patency, lesions are more severe including proliferative endarteritis and interstitial granulomatous pneumonia, as displayed in this case. Vascular lesions are characterized by proliferative endarteritis, including thrombosis, thickening of tunica intima by fibromuscular tissue, and medial hypertrophy with infiltration of eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells.2

Coagulation abnormalities are commonly seen in association with A. vasorum infection. A prolonged activated partial thromboplastin or prothrombin times, thrombocytopenia, and increases in circulating D-diameters and fibrin degradation products suggests disseminated intravascular coagulation.2,4 Affected dogs may have petechiae and ecchymoses in multiple tissues. The cause of this coagulopathy is unknown but may represent thrombosis triggered by parasite proteins or endothelial damage from adult and larval nematodes.2

Cerebral lesions to include mass lesions and areas of hemorrhage are noted as a combination of aberrant larval migration as well as the previously described coagulopathy.

The moderator reviewed a Movat’s pentachrome stain and demonstrated a mural change in the branches of the pulmonary arteries which the moderator interpreted as myointimal proliferation. In this condition, vascular smooth muscle cells migrate into the tunica intima, undergoing both proliferation and secretion of extracellular matrix and collagen. This non-specific change results from endothelial activation and is often seen in cases of heartworm infection.

Contributing Institution:

Utrecht University

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathobiology

Yalelaan 1

3584 CL Utrecht

The Netherlands

www.uu.nl/faculty/veterinarymedicine/EN/labs_services/vpdc

References:

- Bourque AC, Conboy G, Miller LM, et al. Pathological findings in dogs naturally infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20(1):11–20.

- Caswell JL, Williams KG: In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., pp. 648. Elsevier Limited, Philadelphia, PA, 2007.

- Gallagher B, Brennan SF, Zarelli M, et al. Geographical, clinical, clinicopathological and radiographic features of canine angiostrongylosis in Irish dogs: a retrospective study. Ir Vet J. 2012;65(1):5.

- Ramsey IK, Littlewood JD, Dunn JK, et al. Role of chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation in a case of canine angiostrongylosis. Vet Rec. 1996;138:360–363.

- van Doorn DCK, van de Sande AH, Nijsse ER, et al. Autochthonous Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs in The Netherlands. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:163–166.