Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 18

30 January, 2019

CASE II: B or blank (JPC 4066242)

Signalment: 40 year old male Orange-winged Amazon parrot, Amazona amazonica

History: A 40 year old male Orange-winged Amazon parrot (Amazona amazonica) presented to the Ontario Veterinary College, Health Sciences Center, Avian and Exotics service for a one day history of severe weakness, falling from his perch and inability to right himself or stand. The bird was initially purchased as a hatchling, and lived with the current owners for the last 40 years. There were no other birds in the house. The bird had a previous clinical history of feather plucking and hypovitaminosis A.

On physical examination, the bird was dull and lethargic. There was mild overgrowth of the rhampotheca and nails. Complete blood count and serum biochemistry revealed leukocytosis (white blood cells 28.2 x 10^9/L [reference 1.2-10.1 x 10^9/L], heterophils 21.96 x 10^9/L [78 %; reference 21.9-40.7 %]5) and increased concentration of liver enzymes (AST 1012 U/L [reference range 150-344 U/L]2). Due to the age of the patient and severity of clinical signs, the owners declined further diagnostics and the bird was euthanized.

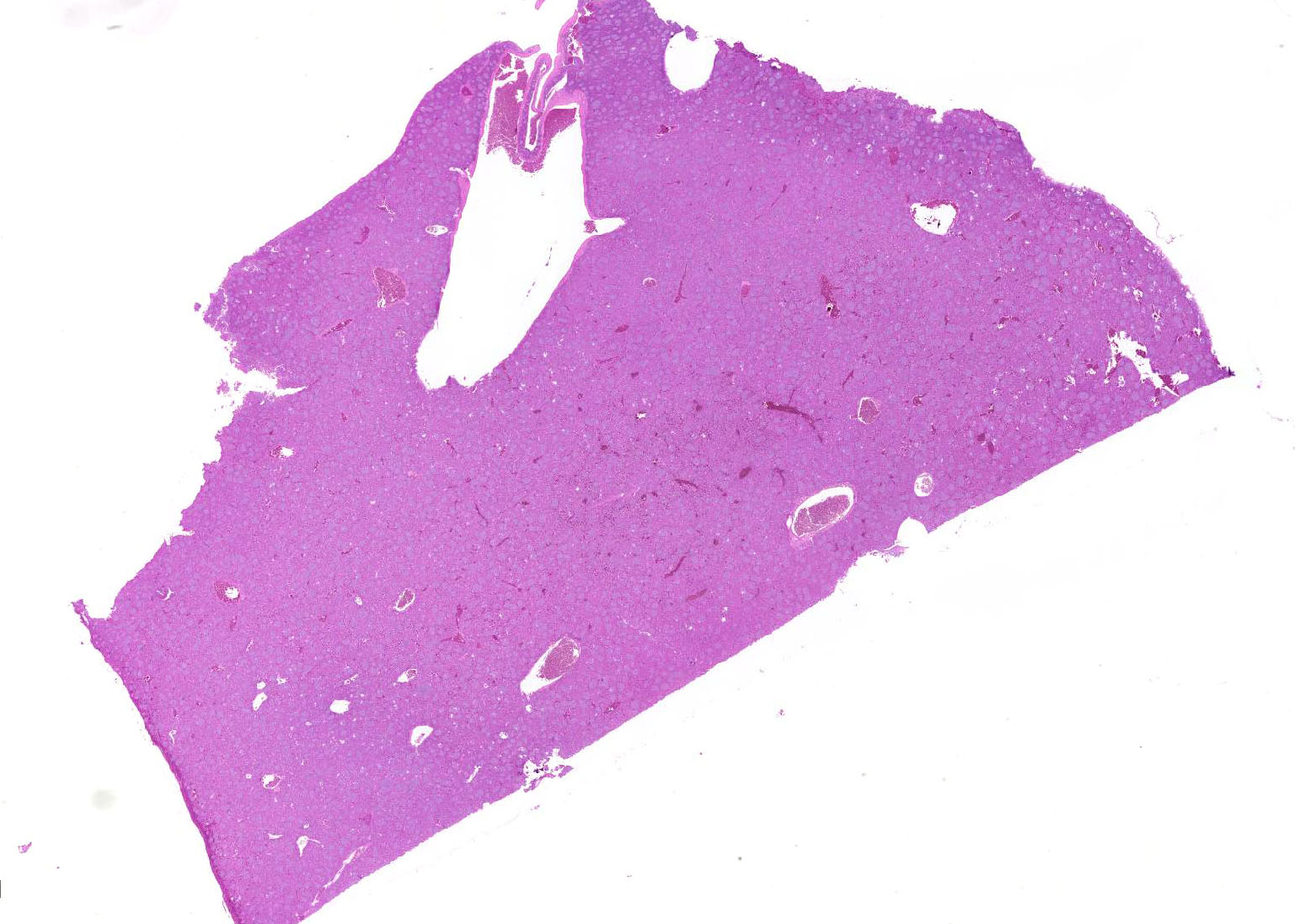

Gross Pathology: The bird was in thin body condition, with decreased subcutaneous fat stores and mildly depleted pectoral muscle mass. The majority of the contour feathers were missing from the ventrum, but down feathers were still present. The gnathotheca was overgrown, with flaking of keratin at the lateral edges. On internal examination, the liver was enlarged and mottled tan-red. The liver weighed 9 grams (2.8 % of body weight). The gastrointestinal tract was empty, with the exception of a small amount of gravel in the ventriculus.

Laboratory Results:

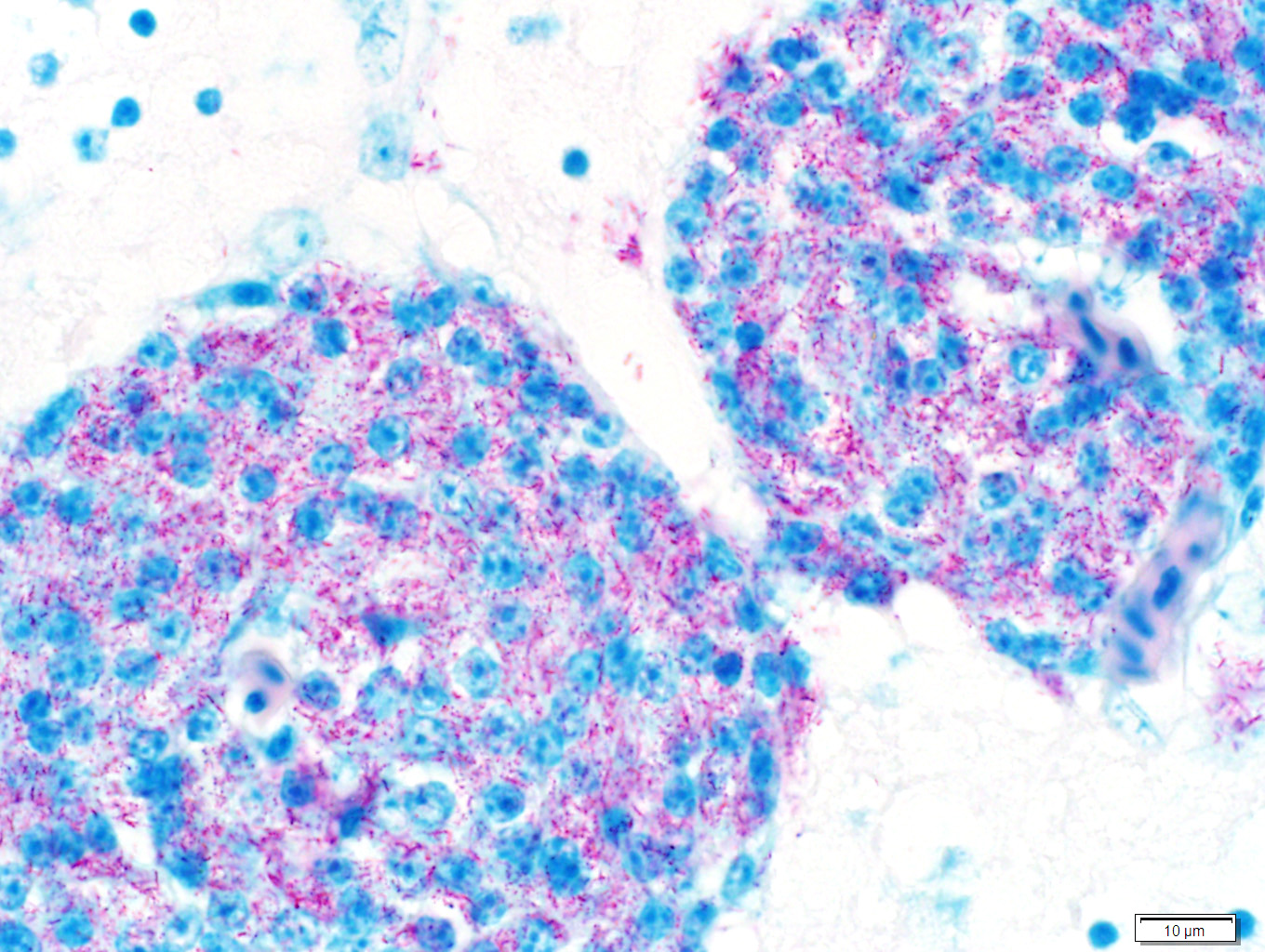

Sections of liver and brain were stained with Ziehl Neelsen acid-fast stain, revealing myriad acid-fast bright red intracytoplasmic bacilli, morphologically compatible with mycobacteria.

Samples of liver and spleen were sent to an external laboratory (Public Health Laboratory, Toronto) for culture and mycobacteria species identification. On tissue smears of both organs, 4+ acid-fast bacilli were seen. GenoType® Mycobacterium molecular genetic test systems (Hain Lifescience) identified the bacilli as Mycobacterium genavense. No mycobacteria were isolated after 7 weeks of mycobacterial culture.

Microscopic Description:

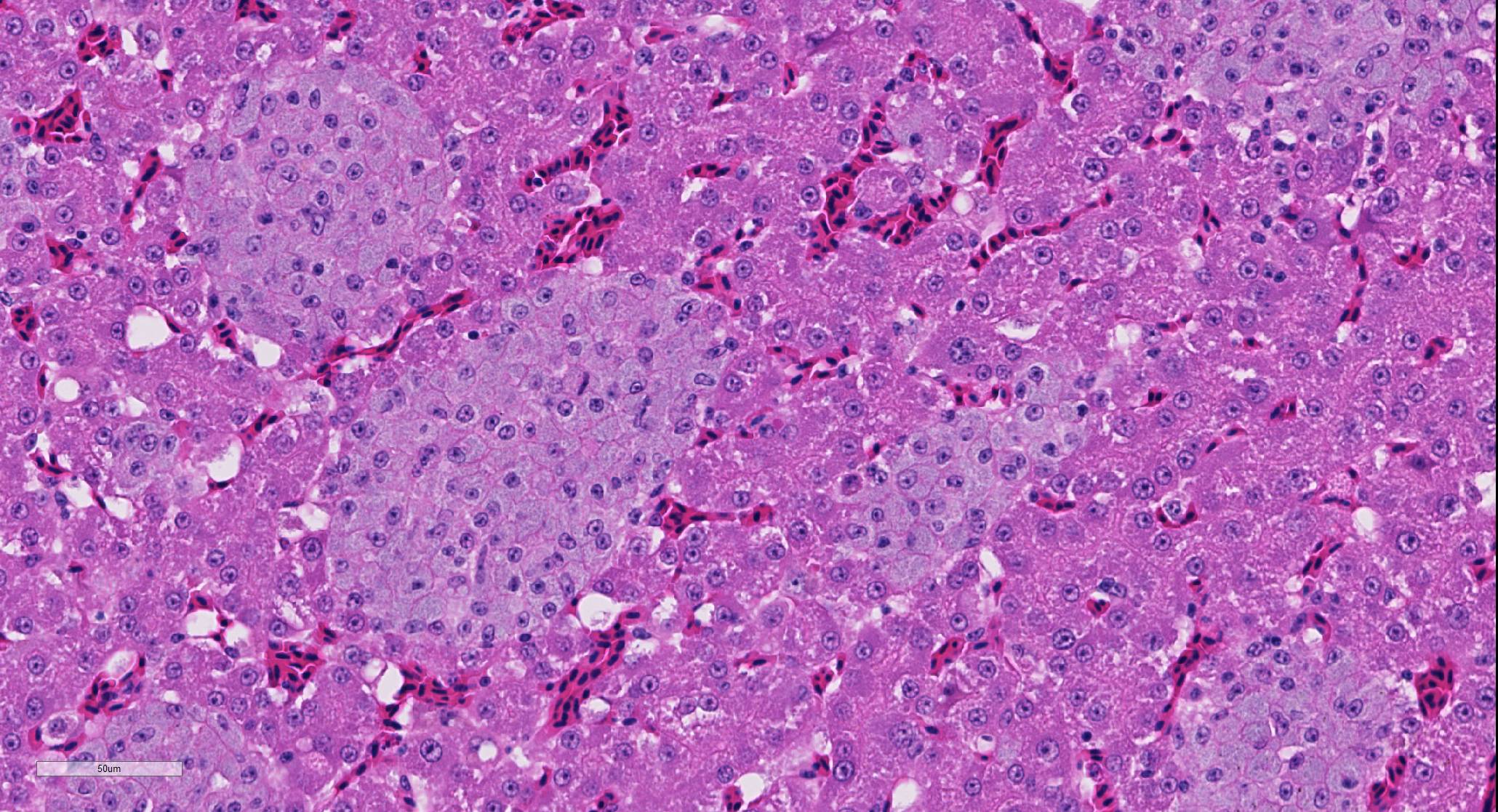

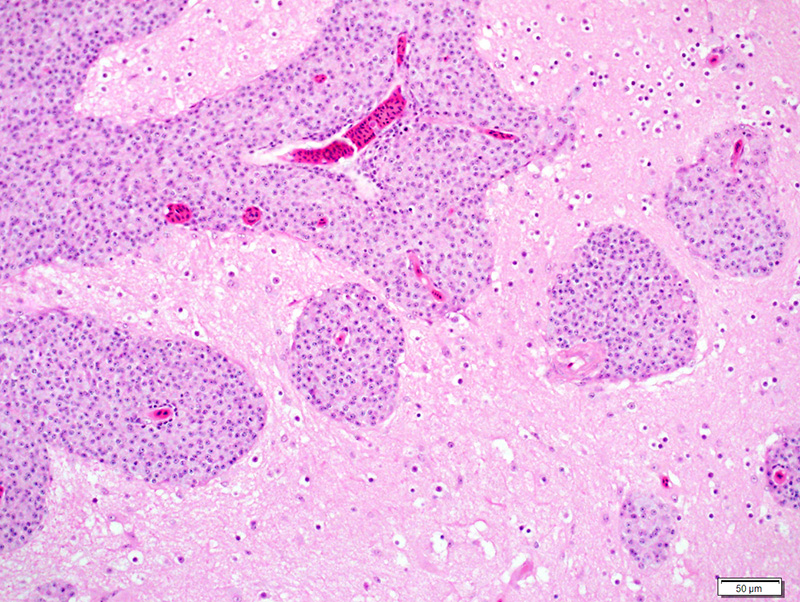

Liver: There are numerous, multiple, well-demarcated, expansile to coalescing, variably-sized (up to 250 µm in diameter) nodular infiltrates scattered randomly throughout the hepatic parenchyma, comprising up to 40% of the tissue. The infiltrates are composed of relatively uniform, approximately15 µm diameter polygonal round cells morphologically compatible with epithelioid macrophages, with distinct cell margins and abundant faintly basophilic cytoplasm containing large numbers of faintly discernable, 1-2 µm long organisms. Nuclei are round and eccentric, with finely stippled chromatin and prominent basophilic nucleoli. Rare larger nodules contain central aggregates of pyknotic cellular debris and amorphous eosinophilic fibrillar material (necrosis).

Brain (tissue not included on slides submitted): Similar infiltrates of macrophages are present beneath the leptomeninges and within Virchow-Robins spaces throughout the sections of brain examined.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: Hepatitis, multifocal nodular, histiocytic with intracytoplasmic bacilli (Mycobacterium genavense).

Contributor’s Comment: A presumptive diagnosis of mycobacterial hepatitis (avian mycobacteriosis) was initially made based on the presence of intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli. As there was potential zoonotic risk in this case,1 samples of liver and spleen were submitted for mycobacterial culture and species identification at a local public health laboratory (Public Health Laboratory, Toronto). The lab identified acid-fast bacilli on direct smears of the tissues and speciated the sample using GenoType Mycobacterium test, which can differentiate between 16 different mycobacterial species (including Mycobacterium genavense).6 Despite the large numbers of bacilli noted histopathologically and on tissue smear, the laboratory was unable to isolate the mycobacteria after 7 weeks of culture.

Avian mycobacteriosis is one of the most common diseases of birds world-wide, affecting pet birds, domestic poultry, zoo collections and wild avian species.8 The disease is often insidious, presenting as a chronic wasting disease with relatively non-specific clinical signs or sudden death with no premonitory signs at all. 1,3,8,10 Antemortem diagnosis is challenging, and diagnosis is often made on characteristic post-mortem and histopathological findings, with or without confirmatory culture and speciation.7, 8 Lesions may exist as multifocal, multi-organ granuloma formation, intestinal paratuberculosis-like histiocytic infiltration, or grossly apparent organomegaly.8 The gross and histological appearance may be impacted by the species of bird affected, or the immune status of the affected bird.8

Mycobacterium genavense has been reported to be the most common mycobacterial species isolated from pet birds,4,8 but Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare are other commonly identified species. Other mycobacterial species (of which there are at least ten identified in various species of birds) are uncommon.7 Mycobacteria are often ubiquitous in the environment, and can be isolated from acidic or wet soil or contaminated water sources.8 Environmental contamination is the presumed source of the organism, and infection is contracted by ingestion of the bacteria. Disease susceptibility is variable depending on the species of bird, with a species predilection (amongst pet birds) for amazons, parakeets, pionus parrots and budgerigars.8 The propensity for a bird to develop disease likely depends on several compounding factors, including nutritional status, stress and overall immune status. Once infected, mycobacteria are phagocytosed by macrophages, often within the intestinal tract, and stimulate a cell-mediated immune response. The exact mechanism of survival of mycobacteria in avian macrophages is not completely understood, but is thought to be the result of impaired enzyme function and phagosome-lysosome fusion.8

Contributing Institution:

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, granulomatous (histiocytic), multifocal to coalescing, marked with numerous intracytoplasmic bacilli.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent and concise review of mycobacteriosis (often incorrectly referred to as “avian tuberculosis”) in birds. Mycobacteriosis is the result of infection by non-tuberculous mycobacteria – over 160 species of ubiquitous environmental bacteria, a small percentage of which have been documented to cause disease in humans and other species. In humans, pulmonary disease is the most common manifestation, and there is well-documented variation in the most common clinical isolates based on location, even within individual countries.9

Once a problem in commercial poultry, today mycobacteriosis is a rare finding due not only to improved husbandry conditions, but most importantly, the rapid turnover of birds from hatching to market – which essentially does not leave enough time for the development of this chronic disease.

A very interesting study performed at the Zoological Society of San Diego (ZSSD) investigated the characteristics and risk factors associated with avian mycobacteriosis in often rare and expensive species.10 The true incidence in many zoo populations is likely underestimated as a result of the chronic nature and long latency period. While previously considered largely an intestinal disease in zoo birds, retrospective study at the ZSSD identified respiratory lesions in 76% of cases, and 27% of cases with only respiratory signs (contrasting with 58% of cases which had intestinal lesions and only 8% with intestinal lesions only) citing a need for screening for respiratory disease as well. The study showed that animals imported into the ZSSD had higher odds of being infected than those born on the property – previous exposure to infected birds prior to import, as well as immunosuppression related to shipping stress (and other forms of stress including conspecific aggression and concurrent disease were considered as potential reasons for this finding. Additional factors included birds that were moved more often between enclosures, species of infected birds, and likely species of infecting mycobacteria.10

The moderator noted the presence of occasional karyomegalic hepatocytes in this section, musing that these may be polyploid and may reflect the age of the bird. The moderator’s preference in the morphologic diagnosis of this lesion is histiocytic which is absolutely acceptable, understandable, and has launched heated discussions around the world for many years. Conference participants showed amazing restraint and tolerance in this instance. The moderator concluded the discussion with a review of mycobacterial disease in a number of species, to include fish, amphibia, reptiles, ruminants, and elephants.

References:

- Boseret G, Losson B, Mainil JG, Thiry E, Saegerman C. Zoonoses in pet birds: review and perspectives. Vet Res. 2013, 44: 36.

- Harr KE. Clinical chemistry of companion avian species: a review. Vet Clin Path. 2002, 31 (3): 140-151.

- Hoop RK, Bottger EC, Ossent P, Salfinger M. Mycobacteriosis due to Mycobacterium genavense in six pet birds. J Clin Microbiol. 1993, 31 (4): 990-993.

- Medenhall MK, Ford SL, Emerson CL, Wells RA, Gines LG, Eriks IS. Detection and differentiation of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium genavense by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme digestion analysis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000, 12: 57-60.

- Polo FJ, Peinado VI, Viscor G, Palomeque J. Hematologic and plasma chemistry values in captive psittacine birds. Avian Diseases. 1997, 42: 523-535.

- Ruiz R, Guttierrez J, Zerolo FJ, Casal M. GenoType mycobacterium assay for identification of mycobacterial species isolated from human clinical samples by using liquid medium. J Clin Microbiol. 2002, 40 (8): 3076-3078

- Shivaprasad HL, Palmieri C. Pathology of mycobacteriosis in birds. Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2012, 15: 41-55.

- Tell LA, Woods L, Cromie RL. Mycobacteriosis in birds. Rev sci tech Off int Epiz. 2001, 20 (1): 180-203.

- Wassilew N, Hoffmann H, Andrejak C, Lange C. Pulmonary disease caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Respiration 2016:91:386-402.

- Witte CL, Hungerford LL, Papendick R, Stalis IH, Rideout BA. Investigation of characteristics and factors associated with avian mycobacteriosis in zoo birds. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008, 20: 186-196.