Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 2

August 30th, 2017

CASE I: 16040206 (JPC 4084138).

Signalment: 1 month-old, intact female, Thoroughbred horse (Equus caballus).

History: The owner found her dead in the stall. She was behaving normally the night before. (per rDVM)

Gross Pathology: The conjunctiva, sclera, and adipose tissue are yellow. The liver is enlarged and skeletal muscle is pale. (per rDVM)

Laboratory results: None provided.

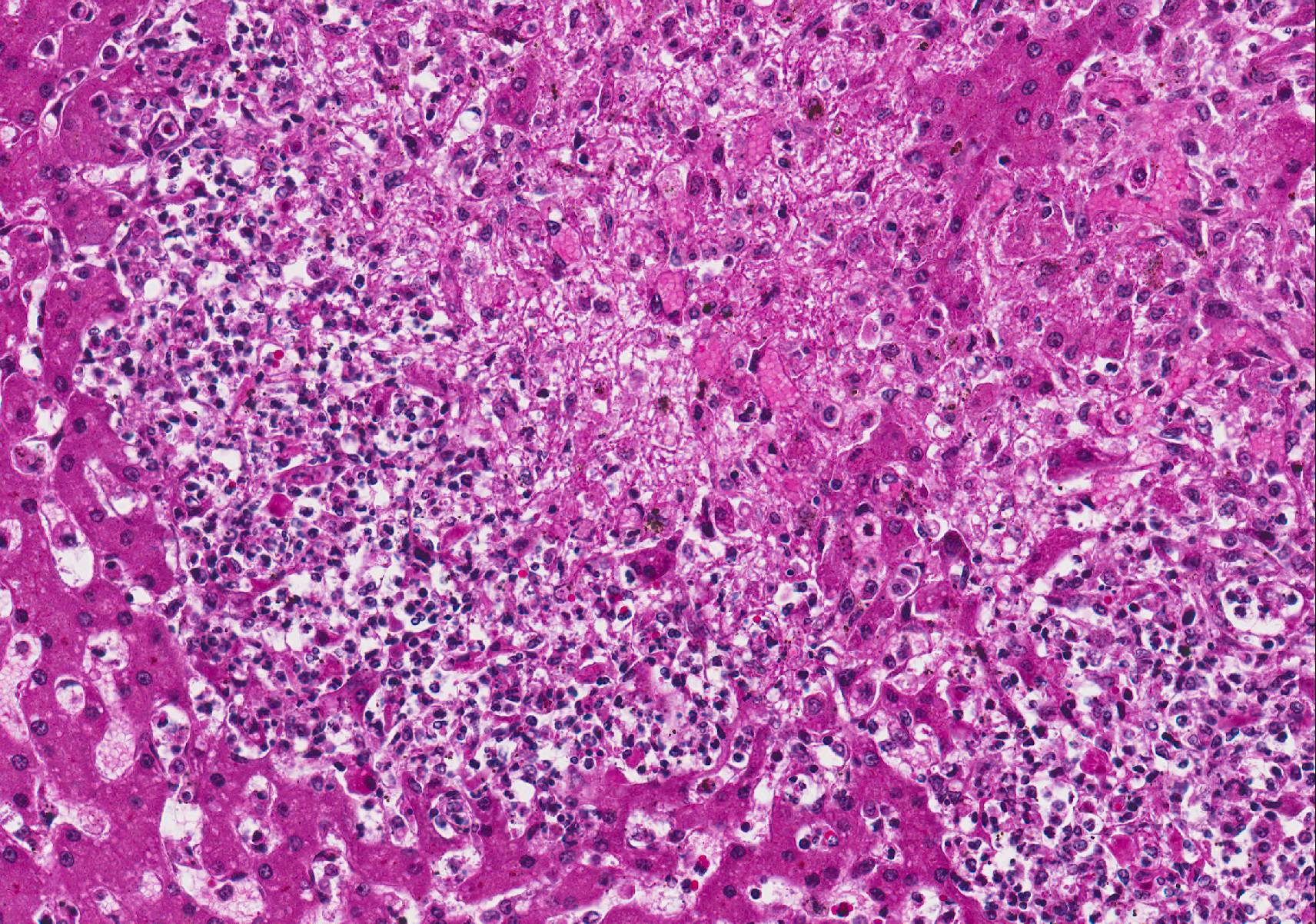

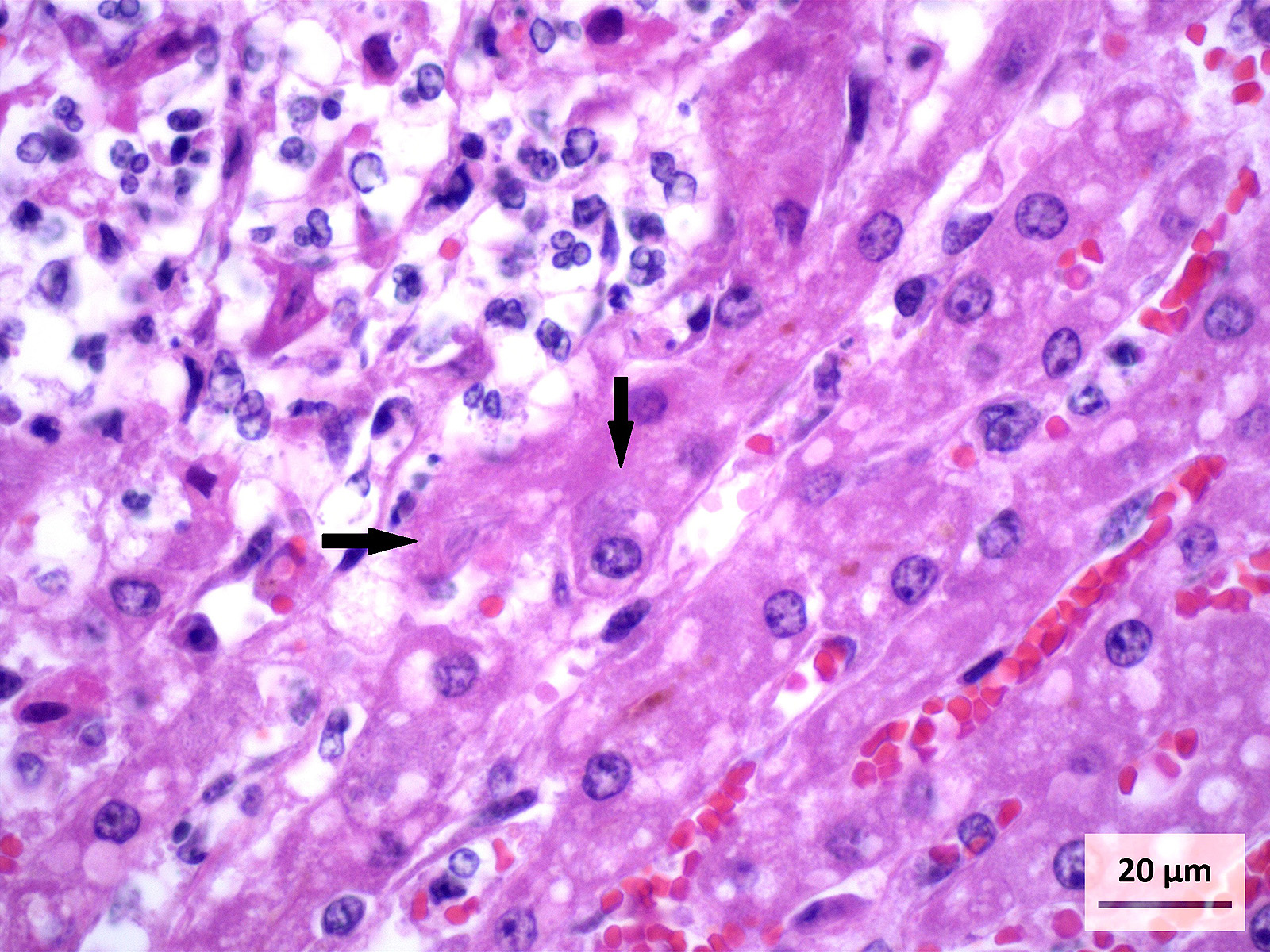

Microscopic Description: Liver (H&E): The liver contains large, individual to coalescing, randomly-placed foci of degenerate neutrophils with fewer macrophages surrounding foci of necrotic hepatocytes admixed with cellular debris. Adjacent peripheral hepatocytes are shrunken, angular, and hypereosinophilic with small, pyknotic nuclei and contain intracytoplasmic, long, slender, parallel to cross-hatched bundles of lightly basophilic to negatively staining, 3.5 to 14 microns in length bacilli. Bile canaliculi in areas less affected by inflammation are distended multifocally with golden brown intracanalicular bile. Randomly, many sinusoids are modestly to moderately congested.

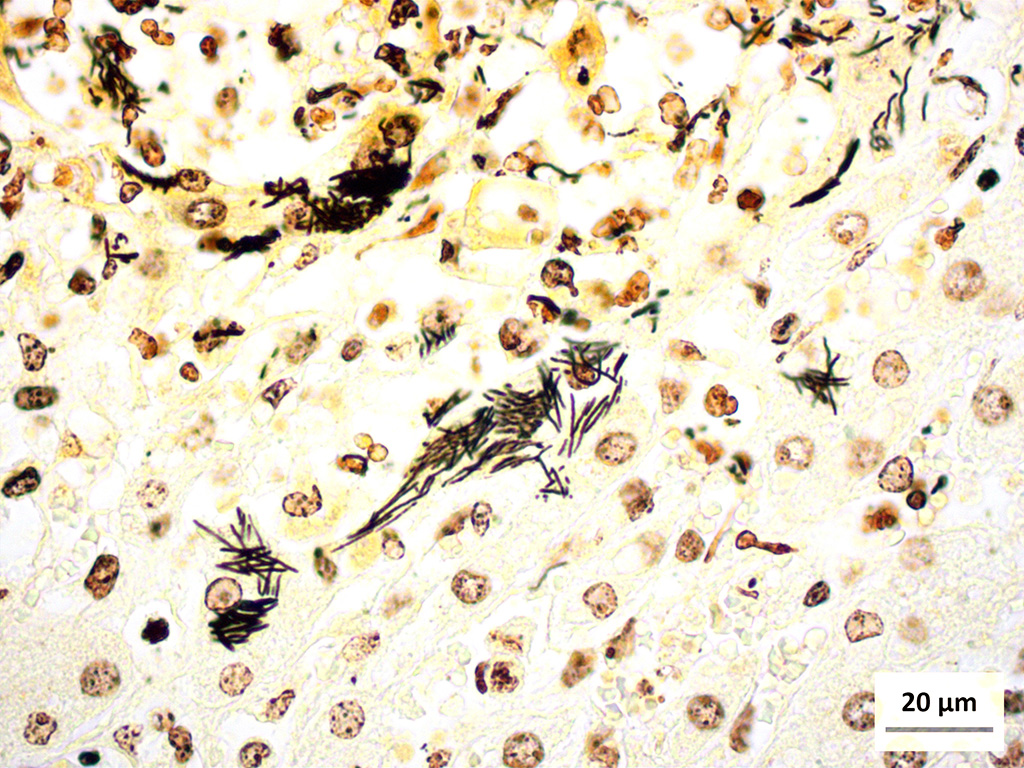

Liver (Steiners silver stain): Myriads of multifocal to coalescing intracytoplasmic, long, slender, parallel to crosshatched bundles of argyrophilic bacilli measuring 3.5 to 14 microns in length are within hepatocytes peripheral to foci of necrosis and inflammation throughout the section.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Liver: Severe, acute, multifocal to coalescing, random, necrosuppurative hepatitis with intralesional bacilli and moderate bile stasis.

Contributors Comment: Tyzzers disease is a bacterial infection that has been reported to affect many different species4. The etiologic agent, originally deemed Bacillus pilifomis, was reclassified in 1993 to the class Clostridia based on genetic sequencing of the 16S rRNA4. Clostridium piliforme is a filamentous, spore forming, gram negative, argyrophilic, obligate intracellular bacterium.

Adult horses are relatively resistant to clinical infections and harbor C. piliforme as part of their normal gastrointestinal microbiota. The upregulation of IL-12 has been explored in laboratory mice experimentally infected with C. piliforme which aids in resistance to this infection and others7. Foals under 6 weeks of age however are typically fatally affected. Transmission in foals is thought to be via a fecal-oral route due to coprophagia of the dams feces during the early weeks of neonatal life6.

Bacteria gain access to intestinal mucosal cells and by an unknown mechanism travel to and infect hepatocytes where it replicates and causes hepatocellular death. The incubation period can be as long as seven days until clinical signs first appear. At this time, nonspecific signs including anorexia, depression, fever, jaundice, and diarrhea may be observed6. These signs can be subtle, which is why many foals present as a found dead case. Due to the rapid course of disease, treatment typically is unrewarding.

This case was a classic presentation of clinical disease. The age of the foal (4 weeks old) places it in the susceptible age range for acquiring the bacteria from coprophagic practices6 and allows for a week long incubation period. Foals become coprophagic during the second week of life and continue the practice through the fifth week6. Typically foals born late in foaling season, from mid-March through May, have a higher prevalence of infection.5, 6 Seventy-seven percent of cases occur in these foals where as 23% of cases occur foals born between January to early March6. This is thought to be due to environmental changes and diet which impact the mares microbiota6. Heavy rainfalls, wildlife reservoirs, and spores contaminating the soil perpetuate the bacteria within the environment for extended periods of time7. Nutrient-dense diets are thought to increase incidence of infection as well and correlate with the overrepresentation of Thoroughbreds and other performance breeds associated with this disease.

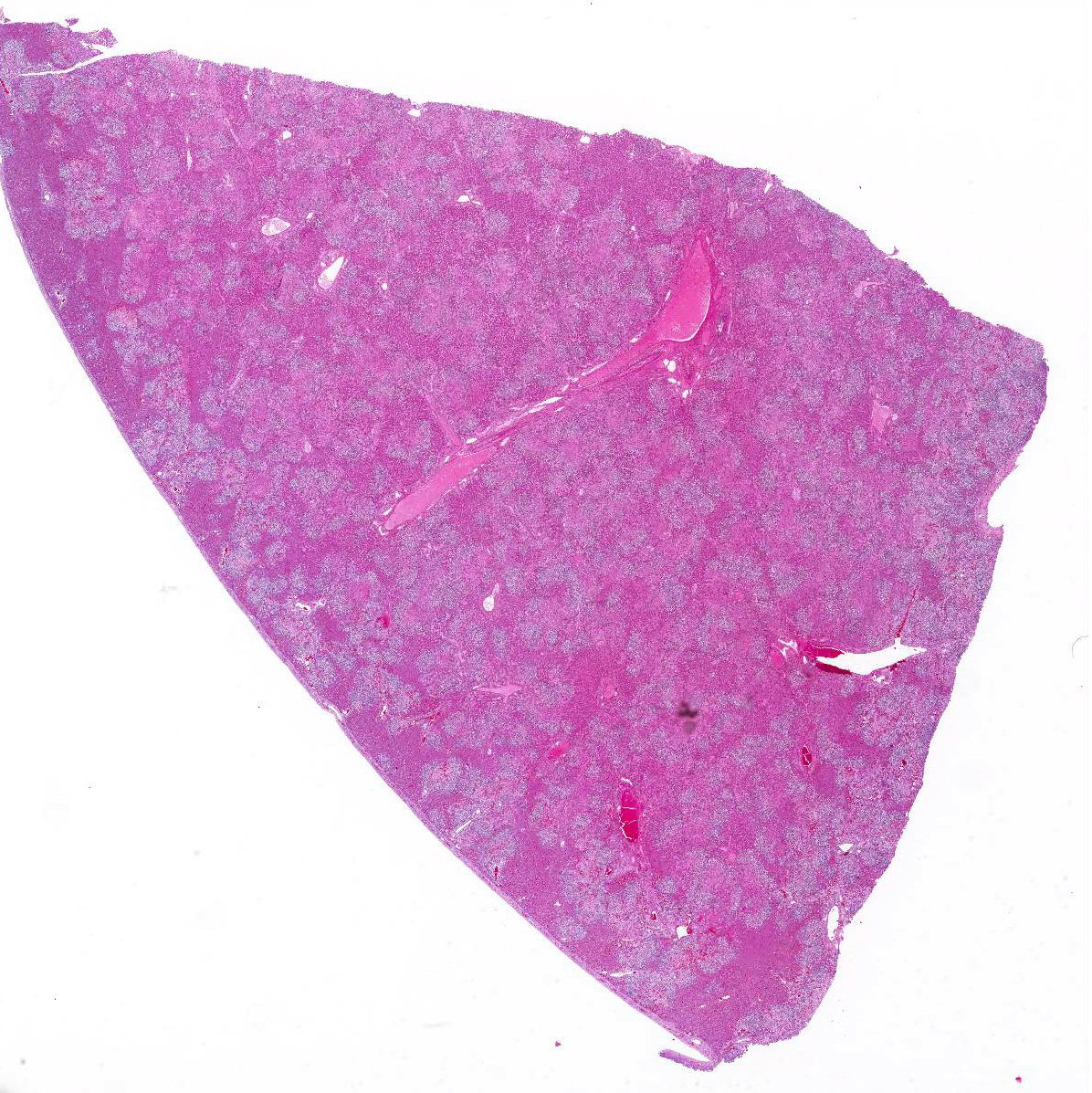

The provided history of behaving normally and then finding the foal dead is also typical of this infection, especially in younger foals. Foals closer to the six weeks of age typically display the nonspecific signs described above for 24-48 hours before death; whereas younger foals usually are found dead with no outward signs of illness6. Icterus is a common sequelae of hepatic damage; however, hepatomegaly is not a common gross finding. We interpret this to be due to the prominent inflammatory cell infiltrate in the necrotic lesions (fig. 1). Our initial suspected diagnosis of Clostridium piliforme (fig. 2) was confirmed by the positive Steiners silver stain demonstrating black, argyrophilic bacilli bordering foci of necrosis (figs. 3, 4). An antemortem diagnosis of Clostridium piliforme has been historically challenging as the bacteria does not grow on conventional media; however, a nested PCR has been developed for in vivo clinical diagnosis using feces as an inexpensive way of confirming the Clostridium piliforme5.

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, random, marked, with numerous intracytoplasmic bacilli, Thoroughbred, equine.

Conference Comment: This case demonstrates a classic example of Tyzzers disease in a foal resulting in acute necrotizing hepatitis. Participants description and discussion mirrored much of what was offered by the contributor. A Warthin-Starry stain was viewed during the conference which beautifully demonstrates the argyrophilic intracellular bacteria lying in sheaves or bundles within hepatocytes located at the periphery of necrotic foci.3 As the contributor aptly notes, C. piliforme-induced lesions in the liver are generally acute and began as foci of coagulative necrosis. As neutrophils are recruited to phagocytize necrotic hepatocellular debris, additional tissue damage results in foci of lytic necrosis, the predominant type of necrosis in this case.

The contributor provides an excellent review of the clinical findings, pathogenesis, gross and microscopic lesions in foals. Additionally, the conference moderator reviewed several susceptible laboratory animal species which present with characteristic lesions not necessarily associated with the classic target tissues (liver, intestine, and heart). Mongolian gerbils are particularly susceptible to C. piliforme infection which can additionally cause diffuse suppurative encephalitis. In rats, infection usually occurs in young animals during the postweaning period and is typically an enterohepatic disease. The typical manifestation in rats is necrotizing and hemorrhagic ileitis with adynamic ileus (also known as megaloileitis). Rabbits usually present with severe, watery colitis that result in high mortality. Microscopically, the characteristic foci of hepatic necrosis are present, as well as, severe focal to segmental necrosis of the cecal mucosa that usually extends transmurally.1

Finally, participants discussed differential diagnoses for random necrotizing hepatitis in foals. Equine herpesvirus-1 causes systemic disease in neonates including multifocal necrosis in liver, spleen, adrenal glands and other tissues with concurrent bronchointerstitial pneumonia. However, there are often prominent intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatocytes and occasional syncytial cells in the lungs.2 Septicemia due to Salmonella sp. or E. coli results in watery foul smelling diarrhea as well as joint lesions, pneumonia, and meningitis (with Salmonella sp.).10 Lastly, sleepy foal disease, caused by Actinobacillus equuli, causes multifocal hepatitis, severe enteritis, and embolic nephritis.3

Contributing Institution:

Oklahoma State University Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Department of Pathobiology

http://cvhs.okstate.edu/Veterinary_Pathobiology

References:

- Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016:137, 201-202, 275-276.

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:568.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:314-315, 317.

- Duncan AJ, Carman, RJ, Olsen GJ, Wilson KH. Assignment of the gent of Tyzzers disease to Clostridium piliforme comb. nov. on the basis of 16S rRNA sequence analysis. 1993. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1993; 43: 314-318.

- Fosgate GT, Hird DW, Read DH, Walker RL. Risk factors for Clostridium piliforme infection in foals. JAVMA. 2002; 220: 785-790.

- Francis-Smith K, Wood-Gush DGM. Coprophagia as seen in Thoroughbred foals. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1977; 9: 155-157.

- Neto RT, Uzal FA, Hodzic E, Persiani M, Jolissaint S, Alcaraz A, Carvallo FR. Coinfection with Clostridium piliforme and Felid herpesvirus 1 in a kitten. J Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2015; 27: 547-551.

- Niepceron A, Licois D. Development of a high-sensitivity nested PCR assay for the detection of Clostridium piliforme in clinical samples. The Veterinary Journal. 2010; 185:222-224.

- Swerczek TW. Tyzzers disease in foals: retrospective studies from 1969 to 2010. Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2013; 54: 876-880.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:166-167, 172-173.

- Van Andel RA, Hook RR, Franklin CL, Besch-Williford CL, Riley LK. Interleukin-12 has a role in mediating resistance of murine strains to Tyzzers disease. Infection and Immunity. 1998; 66: 4942-4946.