CASE III:

Signalment: A juvenile (<1 year old), male bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

History: The eagle was admitted to a local raptor rehabilitation center in Connecticut two days before death, The bird was reported to be 10% dehydrated, showing neurologic signs including seizures and ventral flexion of the neck. The lead level was 4 ug/dL. The eagle received subcutaneous fluid therapy of unreported volume every six hours. The eagle was fed with quail once with assistance but regurgitated all the stomach contents afterward. The eagle was found deceased in the cage on the day of the necropsy submission.

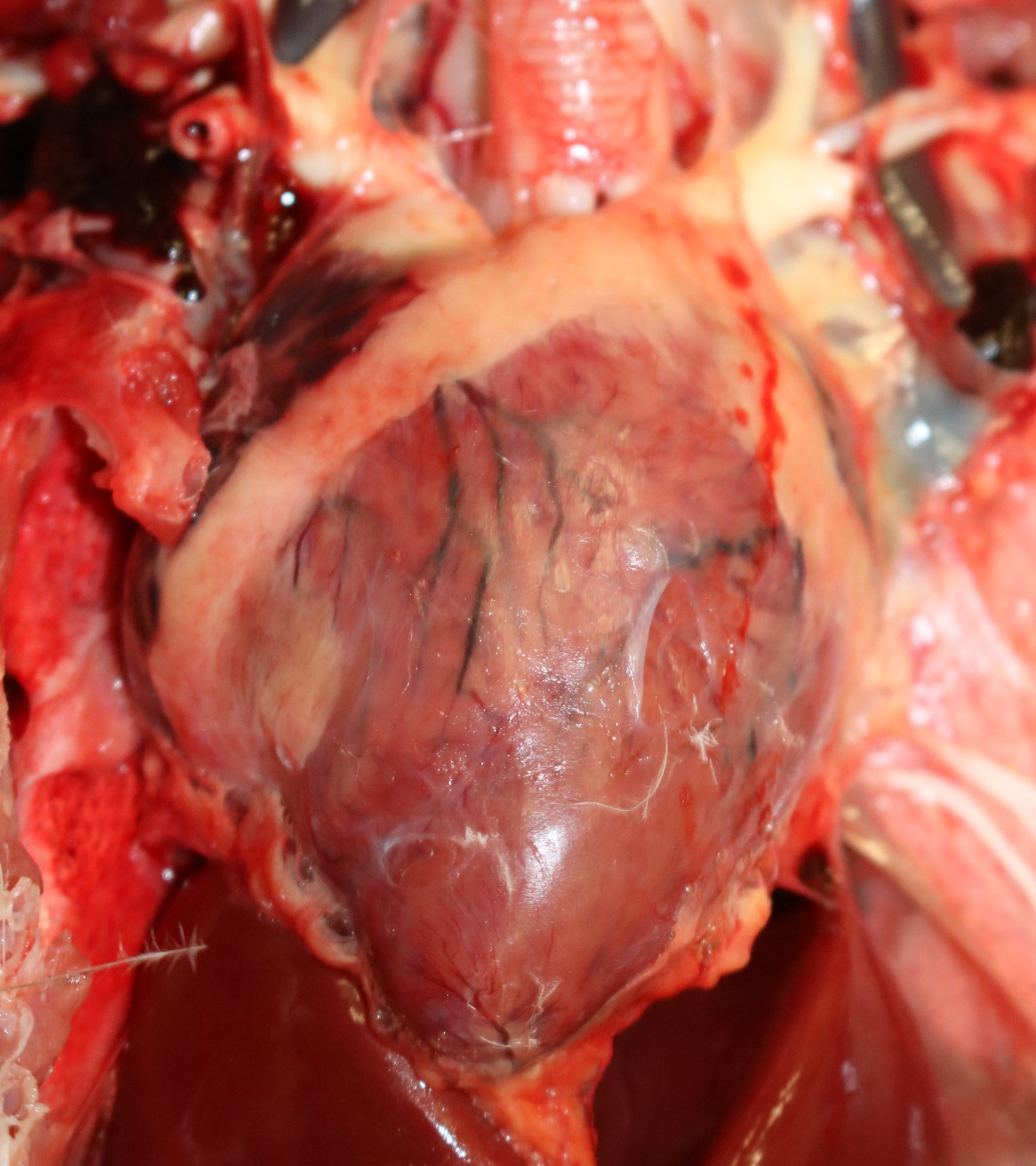

Gross Pathology: This eagle was in adequate nutritional condition, with intra-coelomic adipose stores. A small amount (2-3 mL) of mildly greenish seromucous nasal fluid was discharged from the nostrils, along with two bright red threadlike, 1 cm-long nematodes. The myocardium had multifocal pale areas.

Laboratory Results: Frozen brain tissue was positive for West Nile virus via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) performed by the Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory. A cloacal swab sample was submitted for avian influenza virus (IAV) testing via PCR, and the result was not detected.

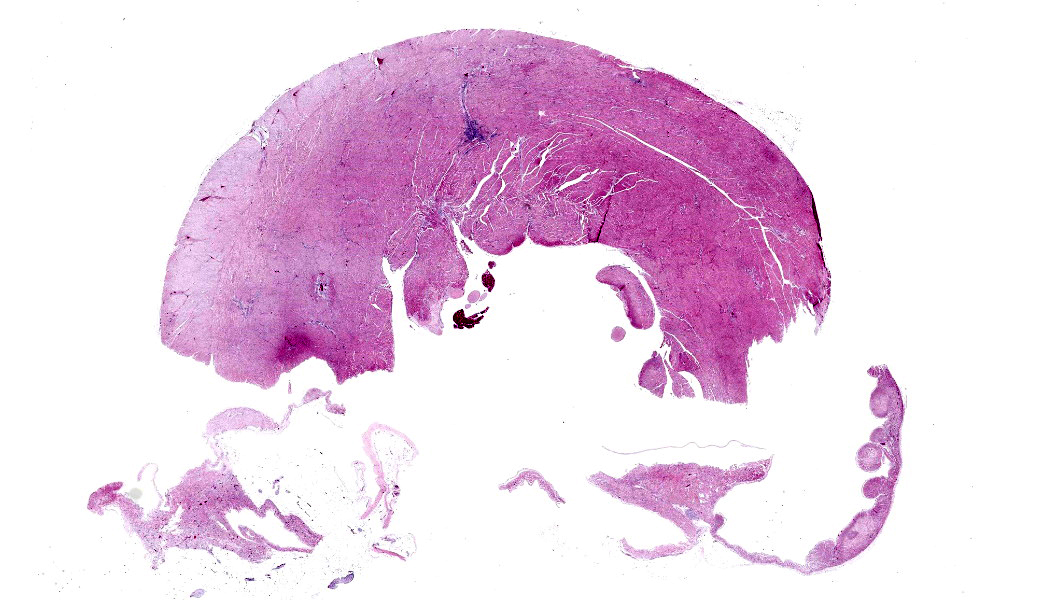

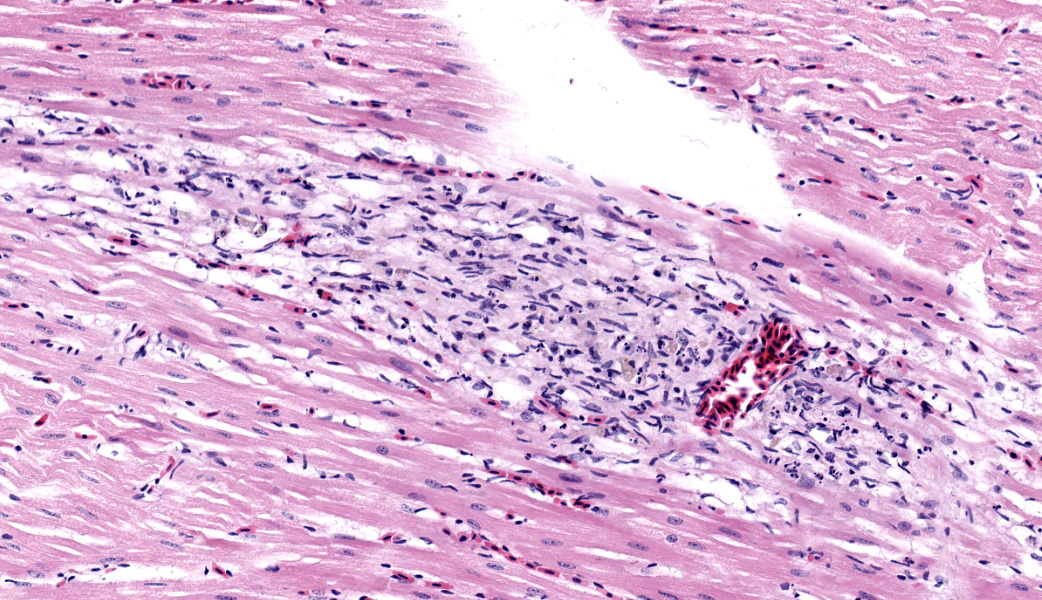

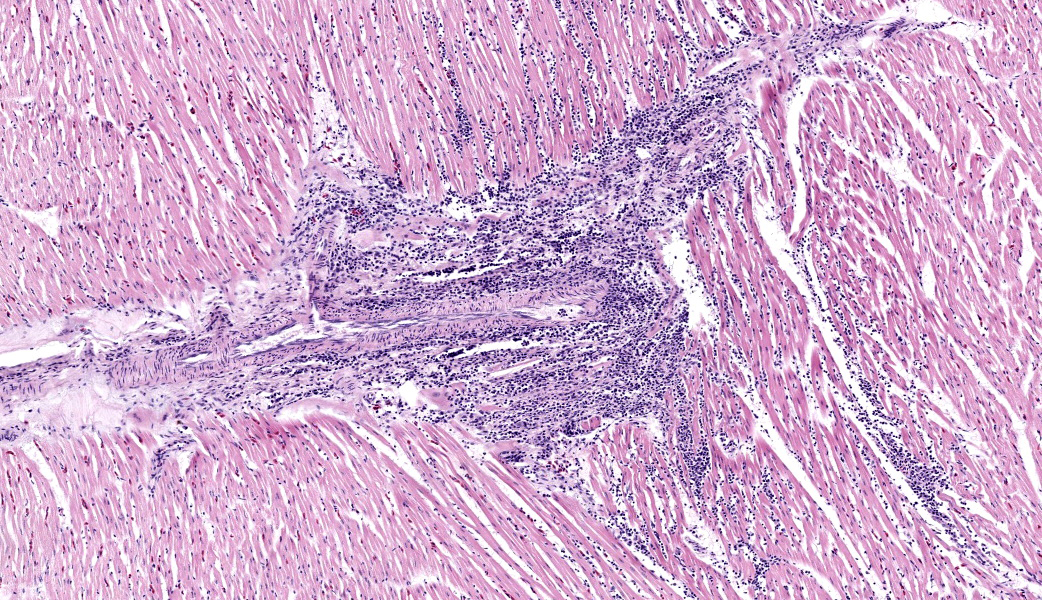

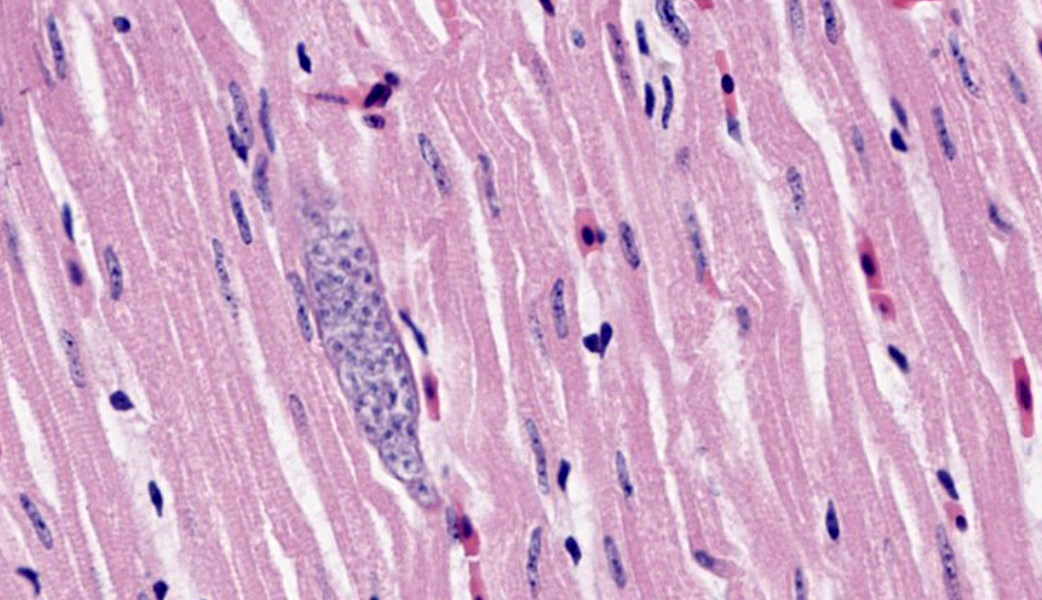

Microscopic Description: Heart: Multifocally infiltrating the myocardial interstitium are small to moderate numbers of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and fewer heterophils admixed with scattered cell debris. Adjacent cardiomyocytes are fragmented with loss of cross striation (myocardial necrosis). Occasionally, the myocardium contains protozoal cysts measuring up to 70 x 20 µm, containing numerous bradyzoites.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lymphohistiocytic myocarditis, multifocal, moderate, with myocardial necrosis and protozoal cysts, heart.

Contributor’s Comment: Additional histologic findings in this case included lymphohistiocytic encephalitis with perivascular cuffing. The histopathological findings in the heart and the brain are consistent with West Nile virus (WNV) infection, confirmed by the molecular testing of frozen brain tissue via qPCR. West Nile virus is an arthropod-borne, enveloped RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. The virus is primarily transmitted by mosquitoes, but direct contact with infected animals and via oral uptake of virus-infected tissues have also been reported.1,3 WNV causes fatal diseases in humans, horses, and a wide variety of birds, including bald eagles.7 Gross lesions caused by WNV in bald eagles included bilaterally symmetrical cerebral pan-necrosis with hydrocephalus ex vacuo, retinal scarring, myocardial pallor, and rounded heart apex.7 Histologic lesions included lymphoplasmacytic encephalitis, myocarditis, pectenitis, and choroiditis.7 Diagnosis of WNV requires a combination of detection of viral antigen and/or RNA or virus-specific antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Differential diagnoses for the protozoa observed in the cardiomyocytes included Sarcocystis and Toxoplasma. Protozoal encephalitis seemed to be unlikely based on the absence of protozoal organisms in the H&E-stained sections, although the co-existence of protozoal encephalitis cannot be ruled out entirely in this case.

The histological characteristics of the nematode in the trachea are consistent with tracheal worm (Syngamus trachea), and this finding is considered incidental in this case.

Contributing Institution:

University of Connecticut Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

61 N Eagleville Rd (yes, Eagleville), Storrs, CT 06269

JPC Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Heart: Myocarditis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, chronic, multifocal, moderate, with cardiomyocyte necrosis.

- Heart, cardiomyocytes: Intrasarcoplasmic apicomplexan schizonts, multiple.

JPC Comment: This case was challenging due to the subtlety of the myocardial necrosis, but conference participants astutely managed to come up with a reasonable list of differentials, all of which must be considered in cases of myocardial necrosis in Bald eagles: lead toxicosis, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), and West Nile virus (WNV). All participants basically waved “Hello”, to the protozoal bradyzoites in the myocardium and drove on, realizing that, although fun to look at, they were likely not the cause of this bird’s lesions and are a common finding in wild avians.

WNV was first isolated in Uganda in 1937 but did not rise to notoriety until its relatively recent spread throughout Europe and the Americans.2 Within the US, WNV broke onto the scene in the summer of 1999 in New York City as an unknown cause of high mortality in bird populations and an encephalitis of unknown origin in horses.5 These cases in animals preceded the disease in humans, which ultimately resulted in 62 deaths in this initial outbreak. From the US outbreak, WNV spread to Canada and Mexico, where it was identified in both countries in 2002. WNV continues to cause occasional outbreaks with severe neurological disease in both humans and horses, and is maintained in the environment predominantly within wild bird and mosquito populations.2,5

Birds are the main vertebrate hosts of WNV.2,5 They are usually asymptomatic, but if clinical signs do manifest, they most commonly include ruffled feathers, lethargy, difficulty moving, and loss of appetite that can be severe enough to cause emaciation. Affected birds may also have profuse oronasal secretions, dehydration, head tremors, and/or seizures.5 Death of infected birds typically occurs within 24hrs of the onset of clinical signs. Of bird species, corvids are exquisitely susceptible to WNV and the only sign of infection may be that they drop dead out of the sky. Histologically, the most common lesion of WNV in birds is necrosis +/- hemorrhages and the most frequently affected organs are the brain, liver, heart, kidney, and spleen.5 There may also be ocular lesions (i.e., neuritis, retinal inflammation, iris degeneration) that can result in clinical blindness.5

Circling back to the two other primary differentials to consider in this case, the histologic lesions in this case are less consistent with lead toxicosis, but blood lead levels should be considered in any case of this nature. Histologic lesions of lead toxicity in bald eagles are those of a primary vascular injury and are classically characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of small to medium-caliber arteries in the heart, brain, and eyes.4 Blood lead concentrations greater than 4ppm are associated with a higher likelihood of cardiac lesions in bald eagles.4 In cases of HPAI in bald eagles, gross and histologic lesions are similar to those seen in WNV and PCR is required to achieve definitive diagnosis. Histologic lesions of HPAI in bald eagles include a leukocytoclastic and fibrinoid vasculitis, as well as necrotizing and hemorrhagic encephalitis, myocarditis, pancreatitis, adrenalitis, histiocytic splenitis, and anterior uveitis.6

References:

- Banet-Noach C, Simanov L, Malkinson M. Direct (nonvector) transmission of West Nile virus in geese. Avian Pathol. 2003;32:489–494.

- Donadieu E, Bahuon C, Lowenski S, Zientara S, Coulpier M, Lecollinet S. Differential virulence and pathogenesis of West Nile viruses. Viruses. 2013;5(11):2856-80.

Komar N, Langevin S, Hinten S, et al. Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:311–322.- Manning LK, Wünschmann A, Armién AG, Willette M, MacAulay K, Bender JB, Buchweitz JP, Redig P. Lead Intoxication in Free-Ranging Bald Eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Vet Pathol. 2019;56(2):289-299.

- Saiz JC, Martín-Acebes MA, Blázquez AB, Escribano-Romero E, Poderoso T, Jiménez de Oya N. Pathogenicity and virulence of West Nile virus revisited eight decades after its first isolation. Virulence. 2021;12(1):1145-1173.

- Wünschmann A, Franzen-Klein D, Torchetti M, Confeld M, Carstensen M, Hall V. Lesions and viral antigen distribution in bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, and great horned owls naturally infected with H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Vet Pathol. 2024;61(3):410-420.

- Wünschmann A, Timurkaan N, Armien AG, et al. Clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical findings in bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) naturally infected with West Nile virus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2014;26:599–609.