WSC 23-24 Conference 9, Case 2:

Signalment:

10-year-old, female spayed mixed breed, canine (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

This dog presented with an approximately 3- month history of chronic coughing. Thoracic radiographs revealed a multifocal alveolar pattern extending to the caudodorsal lung fields. The alterations appeared to have progressed compared to a radiograph taken 7 weeks prior. The tracheobronchial lymph nodes were enlarged but appeared to be of similar size as noted in the previous radiograph. Due to poor prognosis, humane euthanasia was elected.

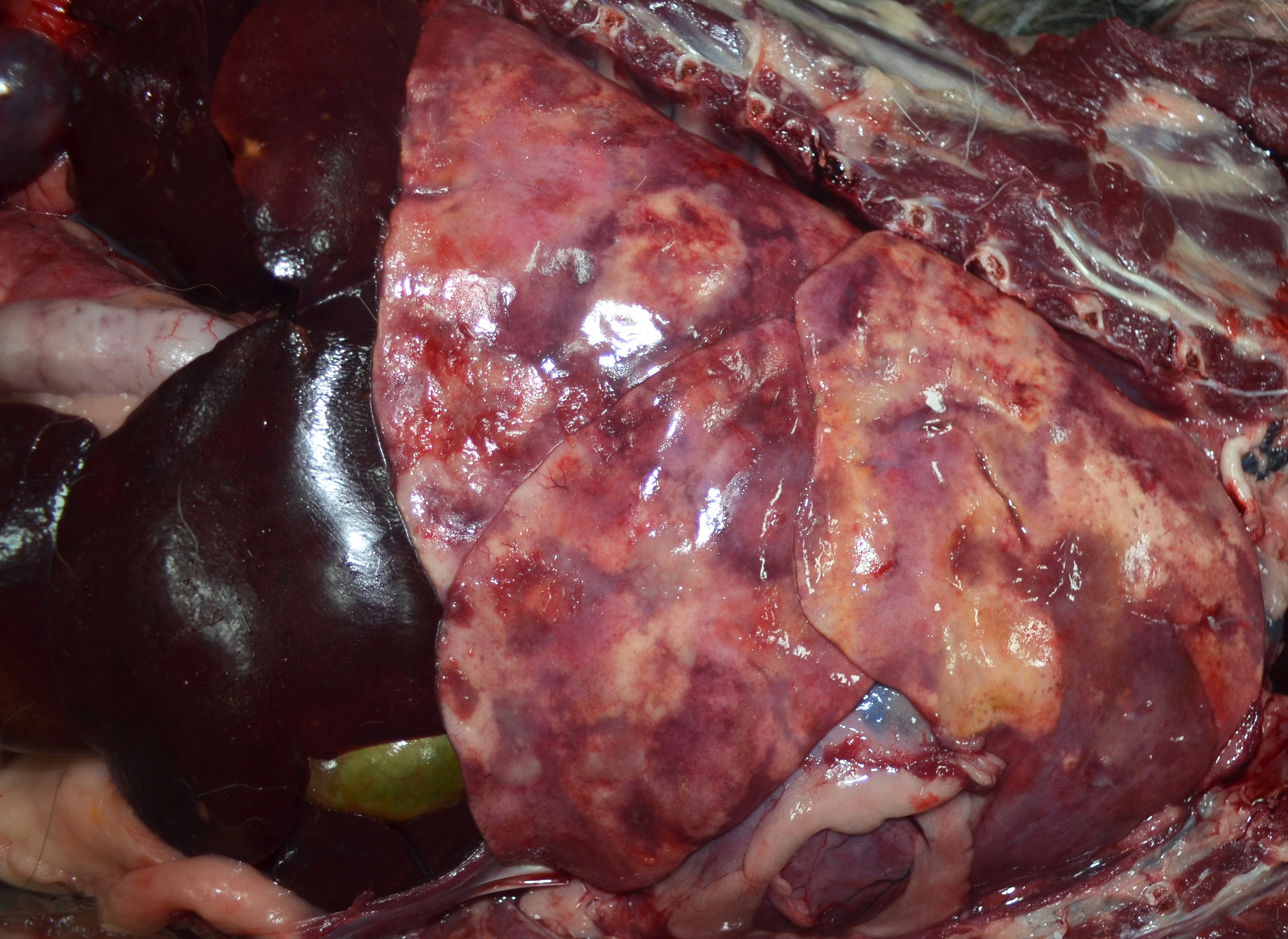

Gross Pathology:

The lungs were diffusely mottled red to dark red with numerous coalescing firm, tan nodules embedded in the pulmonary parenchyma of all lobes. Representative tissue samples floated in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The tracheobronchial lymph nodes were enlarged, ranging in size from 1x2x1 cm to 1.7x4.0x1.5 cm. On the cut surface of these nodes, there were multiple variably sized, random, light to dark brown areas. The liver had several pinpoint to 0.3 cm diameter tan foci throughout.

Laboratory Results:

Bacteriology (Aerobic culture), lung: No bacteria isolated.

Mycology (Fungal culture), lung: No fungi isolated.

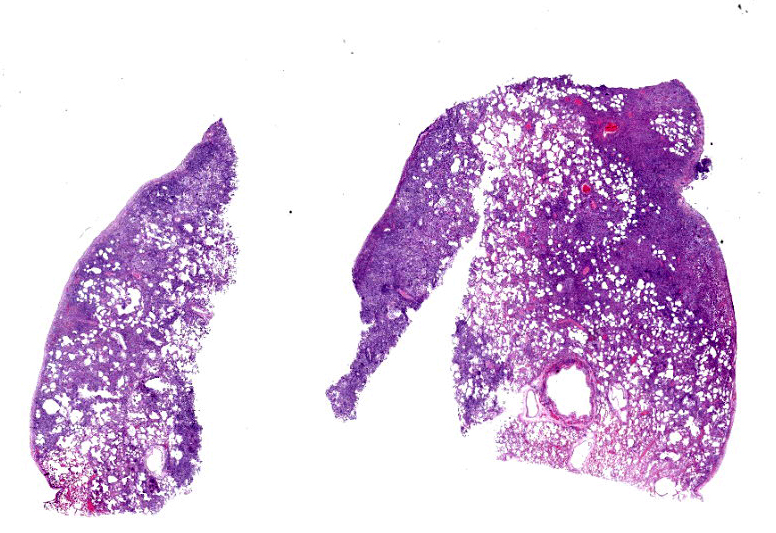

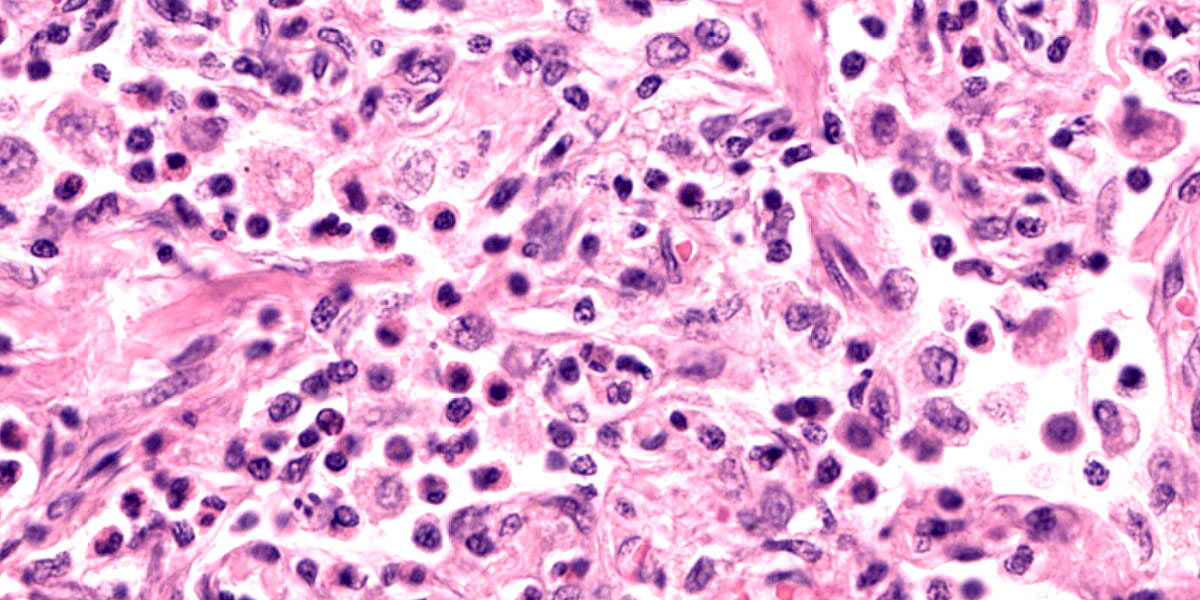

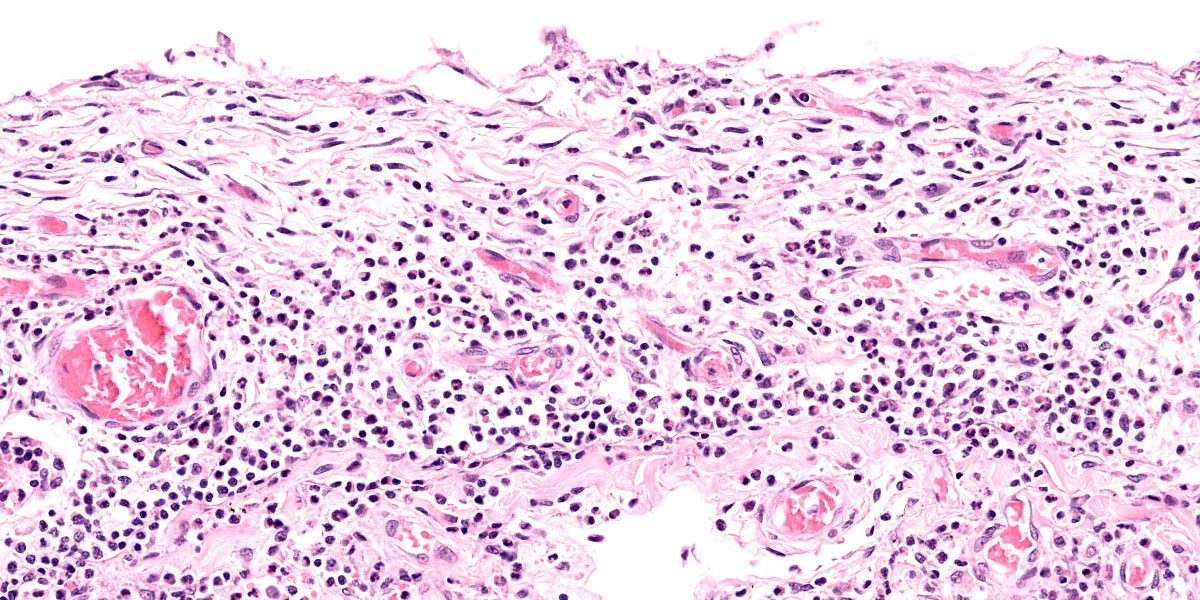

Microscopic Description:

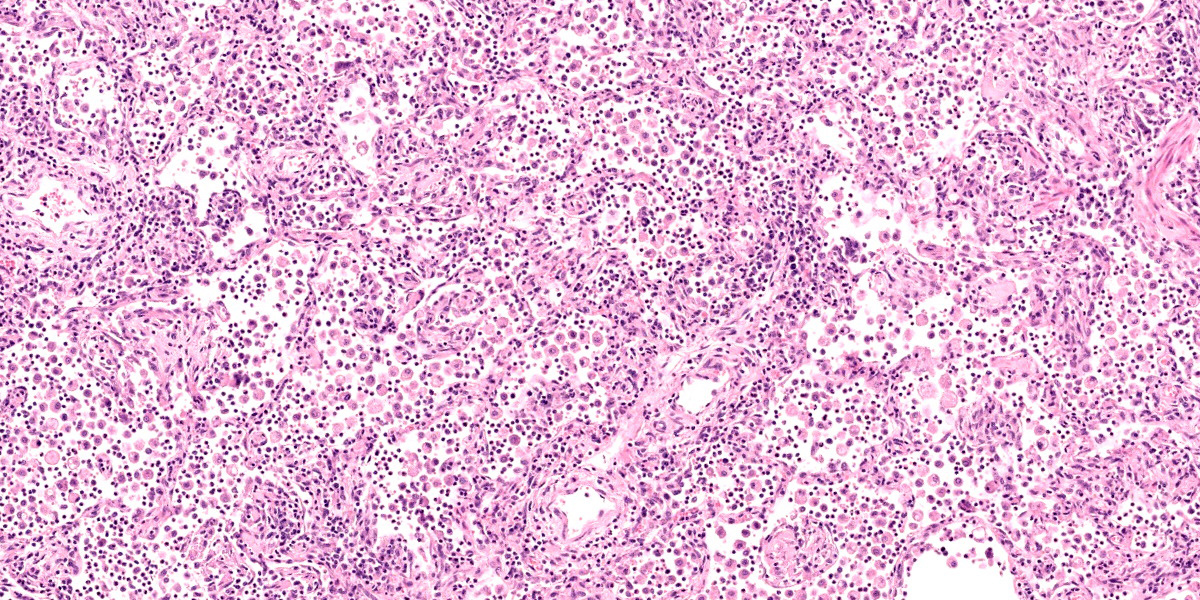

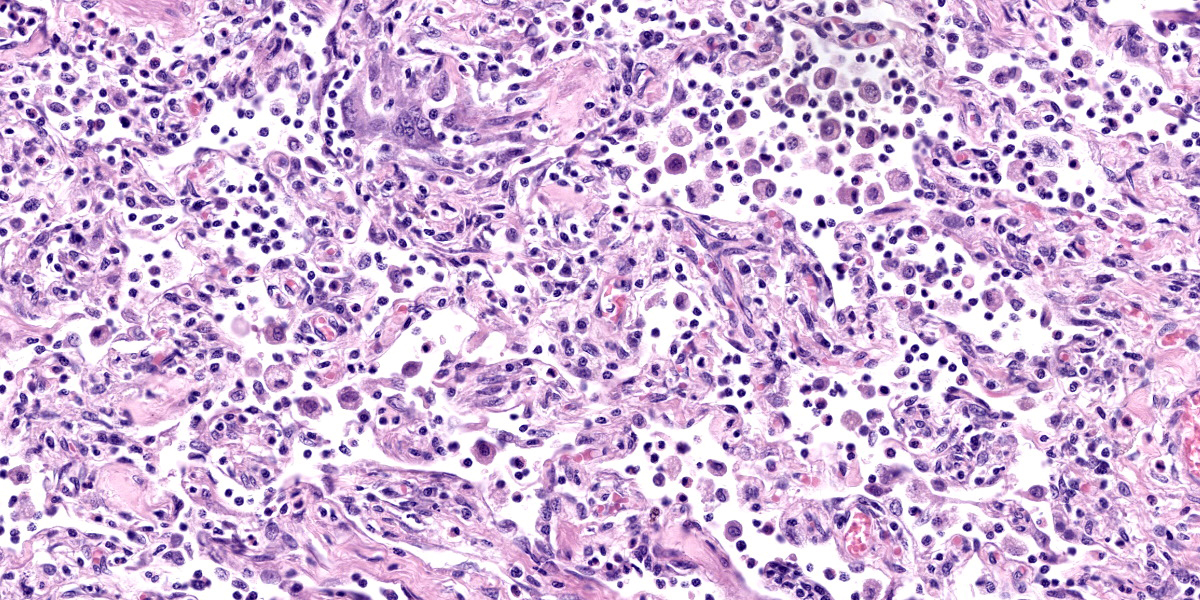

Lung: Corresponding to the coalescing firm tan nodules noted grossly, there is multifocal to coalescing infiltration of the pulmonary parenchyma by large number of mixed inflammatory cells consisting predominantly of macrophages and eosinophils, fewer neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, and occasional multinucleated giant cells, amidst a background of multifocal polymerized fibrin deposits, occasional mild hemorrhage, multiple plump type II pneumocytes, and spindle cells. In some areas, the inflammation concentrates in the bronchiolar and perivascular interstitium, variably extending into the airways (often as epithelium-lined fibrous polypoid structures) and the vascular wall. No microorganisms are apparent, and Gomori's methenamine silver (GMS) staining is negative. Within the remaining areas of the pulmonary parenchyma, the alveoli often contain moderately increased numbers of alveolar macrophages and fibrin strands. In addition, in some sections the pleural surface is multifocally expanded by villous fibrous proliferation with a mixed, predominantly eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate.

Additional histologic findings (sections not submitted) include marked eosinophilic and granulomatous lymphadenitis of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes, mild eosinophilic and granulomatous portal hepatitis, and mild to moderate extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, eosinophilic and granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, marked, chronic (consistent with eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis).

Contributor’s Comment:

Eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis (EPG) is an uncommon, idiopathic disease of dogs with clinical signs of progressive coughing, exercise intolerance, variable dyspnea, and eosinophilia.2,3,6,8,13 EPG is differentiated from the other eosinophil-rich conditions, such as eosinophilic pneumonia and eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP), by the formation of nodules and masses composed of eosinophils, macrophages, and various combinations of other leukocytes within fibrous tissue.1 Some authors have speculated that EPG might represent a progressed form of EBP, which is a more commonly diagnosed idiopathic condition in young dogs.1,2,6,7,9,12 Although eosinophilic airway inflammation and peripheral eosinophilia may be seen in both conditions, EBP is microscopically characterized by airway and pulmonary involvement without granuloma formation or lymph node involvement.2,8 Clinically, EBP responds to immunosuppressive treatment far better than EPG.2,6,8

The cause and pathogenesis of EPG have yet to be determined.4,8 Multiple reports in the veterinary literature have discussed an association between Dirofilaria immitis infection and EPG.1,2,4-6 However, affected dogs do not always have gross, microscopic, or serologic evidence of dirofilariasis.1,2,6,8,10,13 In this case, there was no gross or microscopic evidence of concurrent or previous D. immitis parasitism. In addition, bacterial and fungal cultures of the lung were negative.

Typical gross findings of EPG include firm, consolidated pulmonary parenchyma with multifocal to regionally extensive discrete nodules.2,5,6,10 Similar nodules may be found in the regional lymph nodes, heart, liver, and spleen.1,2,5 Microscopically, the nodules are predominantly composed of eosinophils, macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, and small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes,and plasma cells, and are separated and surrounded by variably thick fibrous connective tissue.1,2,5,6,10 In some cases, eosinophilic and/or granulomatous inflammation is also described in the trachea, kidney, stomach, and small intestine.1 In this case, the tracheobronchial lymph nodes and the liver had similar but milder inflammation as that in the lung, likely all part of the same disease process.

The diversity of the reported affected canine breeds does not suggest a breed predisposition. Although 6 of the 26 dogs with EPG included in a literature review were German Shepherd or German Shepherd crossbred dogs, the authors speculated that this might simply represent the popularity of the breed.1 There does not appear to be sex predilection for EPG in dogs.1

Brown Norway rats, which have been used to study the pathogenesis of asthma, may also develop a spontaneous eosinophil-rich granulomatous pneumonia in the absence of any experimental procedure. While lesions have been observed in rats of various ages, they seem to affect particularly young adult animals. Both sexes are susceptible. Typical gross findings are multiple 1-3 mm diameter, pale tan to gray to red foci scattered throughout the pulmonary parenchyma. Microscopic findings are characterized by multifocal to diffuse granulomatous pneumonia composed of epithelioid cells with or without prominent multinucleated giant cells. There may be marked perivascular and peribronchiolar edema with mixed leukocytic infiltrates rich in eosinophils. Detection of possible infectious agents by serology, bacterial culture, and special stains on affected lungs have all been negative.11

Treatment of EPG includes administration of immunosuppressive and cytotoxic drugs, based on a presumed immune-mediated pathogenesis.6,7 Immunosuppressive doses of prednisone, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide are among the documented treatments; the efficiency of other immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., cyclosporine) is not known.2,6-8,10 The prognosis is poor due either to partial response to treatment or rapid recurrence of respiratory clinical signs after cessation of treatment.2,6,10

Contributing Institution:

Louisiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (LADDL)

School of Veterinary Medicine

Louisiana State University http://www1.vetmed.lsu.edu/laddl/index.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, eosinophilic, organizing, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, severe.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor notes, there is a long-standing debate, referenced in every review of EPG, of a potential association between D. immitis infection and the development of the eosinophilic granulomas that characterize the disease. In the earliest cases, reported in the 1980’s, D. immitis infection was common.2,5,10 Since that time, however, D. immitis infection has become uncommon in reported cases, perhaps indicating the development and widespread adoption of heartworm prophylaxis in the intervening years.1 In fact, a recent study notes that, of the 19 cases of EPG reported before 1988, 8 were infected with D. immitis; of the 7 cases reported since, none had evidence of D. immitis disease.1

Many cases of EPG present with concurrent peripheral eosinophilia and basophilia. The presence of basophilia is a particularly uncommon clinical pathology finding that tends to narrow a differential list significantly. Among the causes for peripheral basophilia are allergic diseases, including eosinophilic granulomas; neoplastic diseases such as mast cell tumors, thymomas, and lymphomatoid granulom atosis; drug reactions; stress (in birds); and parasitism, including Dirofilaria immitis.14 The fact that EPG and D. immitisinfection both provoke this uncommon clinical pathology further stokes suspicion that a casual link underlies this association. Whether the eosinophilia and basophilia is useful diagnostically and whether there is a causal link between D. immitis infection and EPG are currently both open questions that require further investigation.1

There is speculation that EPG might be a more progressed form of eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP), an uncommon, typically steroid responsive condition of young dogs.3 The eosinophilic bronchitis with epithelial hyperplasia, ulceration, and/or squamous metaplasia that characterize this condition tends to destroy airway walls and leads to bronchiectasis in 25% of cases.3 EBP is currently thought to be immune-mediated, but a diagnosis of EBP requires that more specific conditions be ruled out. These include the tracheobronchial parasites Crenosoma vulpis, Eucoleus aerophilus, and Oslerus osleri; the lung worms Angiostrongylus vasorum and Filaroides hirthi; Dirifilaria immitis infection; and neoplasia, including pulmonary carcinoma, histiocytic sarcoma, lymphoma, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.3

Conference discussion initially focused on the lesion distribution, which is predominantly parenchymal and is curiously concentrated subjacent to the pleura. Dr. Williams prefers to describe this distribution, which most closely resembles an interstitial pattern but isn’t an exact fit to any of the establish patterns, as simply pneumonia. Conference participants also remarked on the lack of a clear nodular pattern that is typical of EPG.

A particular striking histologic feature in this slide is the irregular, eosinophilic, densely cellular material found protruding into airways and multifocally adhered to alveolar walls. Though most conference participants interpreted this as alveolar fibrosis, Dr. Williams interpreted these areas as ancient remnants of previously suffered bouts with an extremely exudative inflammatory process. The fibrous tissue left behind represents attempts by the lung to repair the damage, referred to as organizing pneumonia. In less affected areas of lung, alveoli are multifocally mineralized, a lesion that likely represents a more recent stage of injury, providing multiple temporal stages in the disease process in one slide.

Participants also discussed the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate at length. While eosinophils are clearly the main driver of disease in this case, the remainder of the inflammation was characterized by the conference participants as mixed, with large numbers of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes.

Based on these discussions, the JPC morphologic diagnosis highlights the eosinophilic nature of the inflammation and eschews the reference to granulomatous due to the heterogenous nature of the infiltrate. Conference participants also felt that the multifocal foci of organizing pneumonia was an important histologic feature to highlight as it provides a window into pathogenesis and an indicator of chronicity.

References:

- Abbott DEE, Allen AL. Canine eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis: case report and literature review. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2020;32(2):329-335.

- Calvert CA, Mahaffey MB, Lappin MR, Farrell RL. Pulmonary and disseminated eosinophilic granulomatosis in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1988;24:311–320.

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed., vol. 2. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:501-502,513.

- Clercx C, Peeters D. Canine eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2007;37:917–935.

- Confer AW, Qualls Jr CW, MacWilliams PS, Root CR. Four cases of pulmonary nodular eosinophilic granulomatosis in dogs. Cornell Vet. 1983;73:41–51.

- Dehghanpir SD, Leissinger MK, Jambhekar A, et al. Pathology in Practice: Eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis (EPG) with extension into the mediastinal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;254(4):479-482.

- Hawkins EC. Chapter 22: Disorders of the pulmonary parenchyma and vasculature. In: Nelson RW, Couto CG, eds. Small Animal Internal Medicine. 6th ed. Elsevier;2019:348–349.

- Katajavuori P, Melamies M, Rajamäki MM. Eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis in a young dog with prolonged remission after treatment. J Small Anim Pract.2013;54(1):40-43.

- Marolf AJ, Blaik MA. Bronchiectasis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2006;28:766–775.

- Neer TM, Waldron DR, Miller RI. Eosinophilic pulmonary granulomatosis in two dogs and literature review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1986;22:593–599.

- Percy DH, Barthold SW, Griffey SM. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 4th ed. Blackwell Publishing;2016: 160.

- Reinero C. Interstitial lung diseases in dogs and cats, part II: known cause and other discrete forms. Vet J. 2019;243:55–64.

- Von Rotz A, Suter MM, Mettler F, Suter PF. Eosinophilic granulomatous pneumonia in a dog. Vet Rec. 1986;118:631-632.

- Webb JL, Latimer KS. Leukocytes. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan & Prasse’s Veterinary Laboratory Medicine Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Wiley-Blackwell;2011:76.