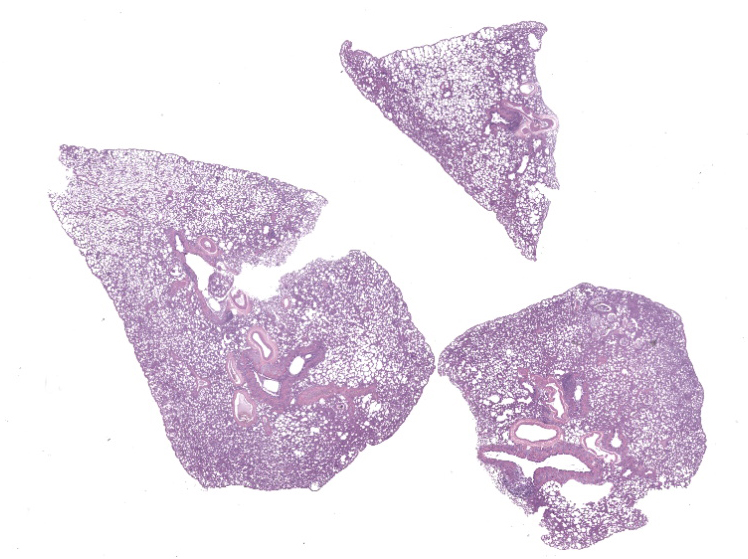

WSC 2023-2024, Conference 19, Case 2

Signalment:

Adult male white-eared opossum (Didelphis albiventris)

History:

The animal was found dead in an urban park in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, and was immediately submitted to necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

There was an extensive area of skin laceration with exposure of bone and muscle in the dorsal proximal portion of the tail. Lungs were pale pink with diffuse decreased crepitation. The myocardium had multifocal to coalescing 0.2 to 0.4 cm white areas. The liver was diffusely yellow and friable. The spleen was markedly enlarged with multifocal to coalescent white-red areas. The kidneys were diffusely yellow with pinpoint multifocal white areas. The pelvis of the right kidney was moderately dilated, as was the right ureter, which was partially obstructed by a white friable plug. The gastric and duodenal lumens had multiple cylindrical white worms which were 3 cm long and 0.3 cm in diameter (morphologically compatible with nematodes).

Laboratory Results:

Samples of liver, spleen and kidney were submitted for bacterial culture. Streptococcus didelphis was isolated from all samples.

The nematodes found in the stomach and duodenum were identified as Turgida turgida.

Microscopic Description:

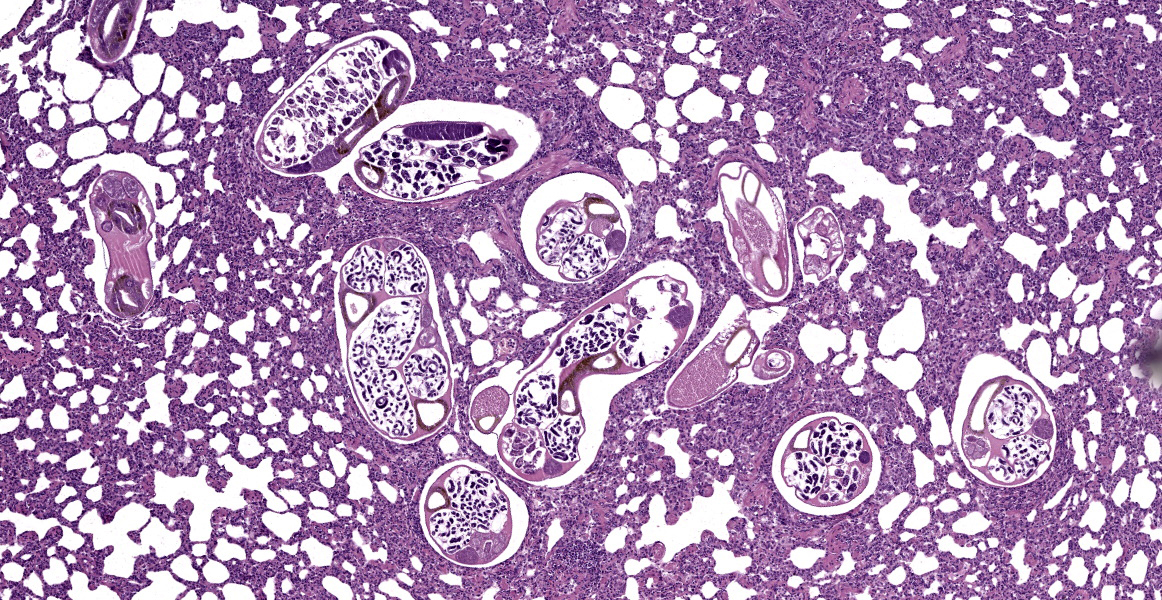

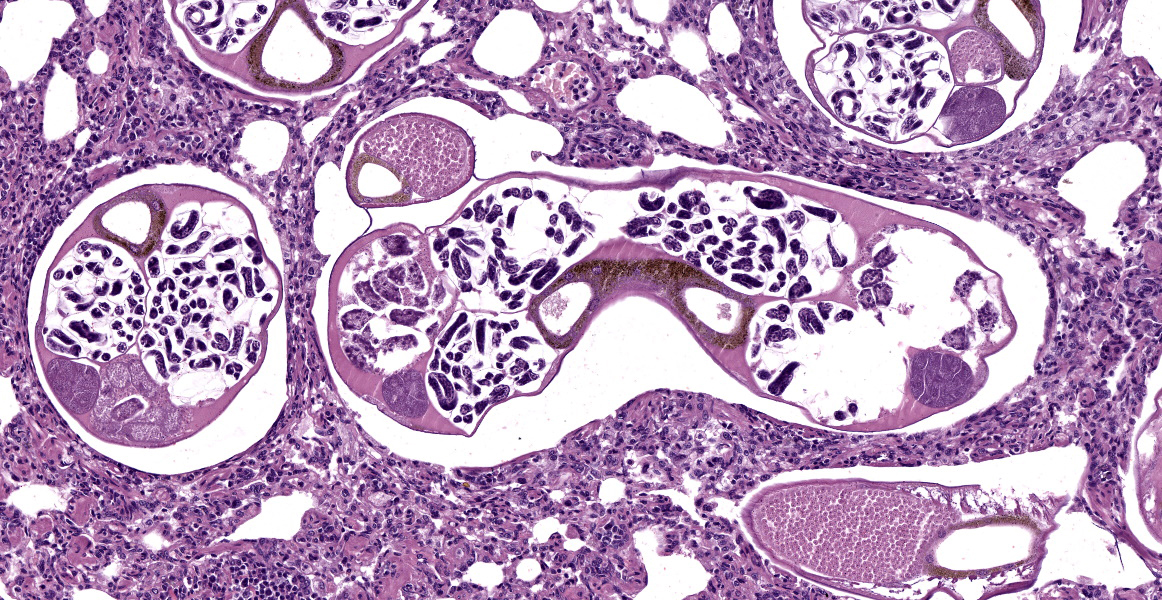

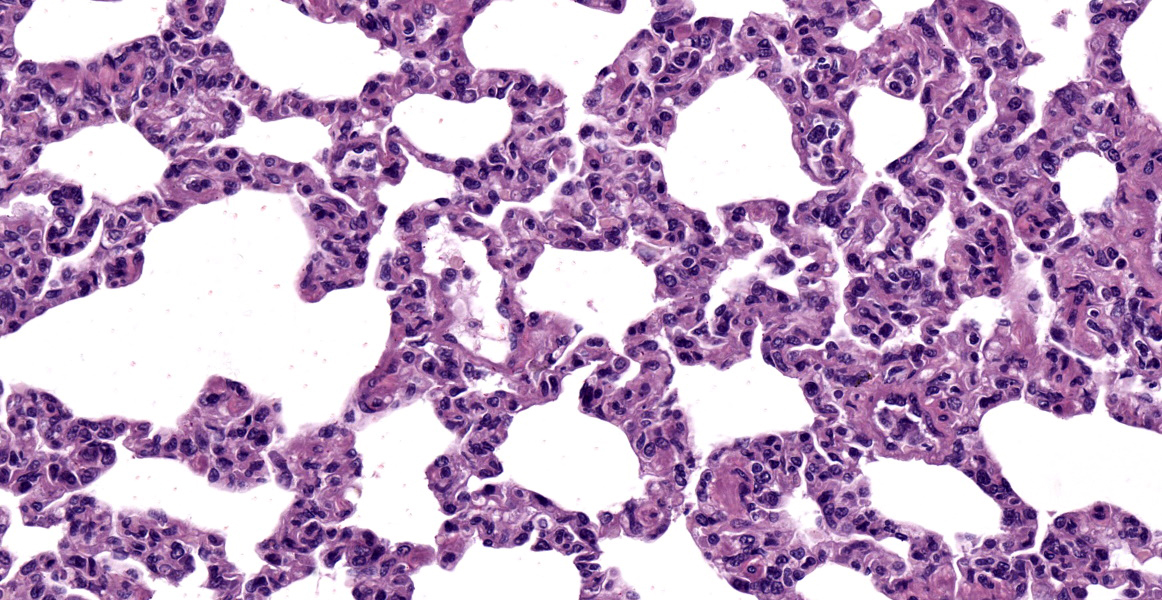

Lung: Bronchi and bronchioles are expanded by moderate amount of mucus, intact and degenerate neutrophils, and some macrophages. Interspersed with the mucus, there was a moderate number of nematode larvae approximately 50 µm in length x 7 µm in diameter. Alveolar septa were diffusely and moderately thick and filled by neutrophils and histiocytes. Multifocally, in the alveolar lumena and terminal bronchioles there are multiple adult metastrongyles approximately 260 µm in diameter. The parasites have a small and ornamented cuticle, a pseudocoelom, an intestine with cuboidal cells full of brown intracytoplasmic granules, a uterus with numerous larvae in females and testes with globose spermatozoa in males. There are mild multifocal areas of rupture and coalescence of alveolar septa (emphysema). Additionally, multifocally there are foamy macrophages in the alveolar septa and lumena adjacent to the adult parasites. Blood vessels are filled with leukocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Lung: Bronchitis and bronchiolitis, catarrhal, neutrophilic and histiocytic, multifocal, moderate, with intraluminal nematode larvae.

- Lung: Interstitial pneumonia, neutrophilic and histiocytic, diffuse, moderate, with nematodes morphologically compatible with Didelphostrongylus hayesi in the lumen of alveoli and terminal bronchioles, and mild multifocal emphysema.

Contributor’s Comment:

White-eared opossums (Didelphis albiventris) are marsupial mammals that inhabit forests and peri-urban areas in Brazil, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, and, according to the IUCN red list, the species is considered of Least Concern for the risk of extinction.3 Parasitic infections are frequently reported in these opossums, often by parasites that also can affect domestic animals and humans, such as ectoparasites, protozoans (Leishmania spp., Toxoplasma gondii, and Trypanosoma cruzi), and helminths (Toxocara sp., Ancylostoma caninum, and Schistosoma spp.).1

Didelphostrongylus hayesi is a nematode of the Order Strongylida and superfamily Metastrongyloidea that infects the lungs of opossums. Infection occurs by ingestion of snails (Mesodon perigraptus and Triodopsis albolabris) which are the intermediate hosts.9 The infection can be mild to severe, and the animals may be asymptomatic or symptomatic, with dyspnea, fever and apathy. Radiographically, the lungs may have a bronchial pattern and fecal examination may support the in vivo diagnosis by visualizing larval stages.7 At necropsy, the lungs may be hyperemic with a cranioventral pattern. Lungs do not collapse when the thoracic cavity is opened, and they are firm, with disseminated micronodules and adult parasites of approximately 1.5 to 2.0 mm may be seen in the bronchi. In cases of mild to moderate infection, as in this case, gross changes may be mild or absent. Histologically, there are larvae and adult parasites in the lumen of bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli, with mucus and an inflammatory infiltrate that can be neutrophilic, eosinophilic, or histiocytic. The infiltrate associated with the adult parasites is mild or absent, whereas larvae and eggs induce a more exacerbated inflammatory response, with granulomatous or pyogranulomatous inflammation.7,8 There is also hyperplasia of the smooth muscle of the bronchi and bronchioles, hyperplasia of the respiratory epithelium, and emphysema.4, 8

Worm infections of the lower airways (trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in domestic and wild animals. Histological lung lesions by helminthic infections can range from mild, such as bronchitis and bronchiolitis in cases of mild infections by Dictyocaulus viviparus, to granulomatous, necrotizing, hyperplastic and emphysematous lesions. The intensity of the lesions will depend on the immune status of the host, as well as the parasite load and reproductive stages of the parasites.2

Traumatic injuries frequently occur in opossums due to their synanthropic habits, whether due to car accidents, or attacks by dogs or people. In this case, the animal presented with areas of skin laceration and systemic involvement by Streptococcus didelphis. Neutrophilic and histiocytic interstitial pneumonia, in addition to being associated with the parasites, may result from the systemic bacterial process. Streptococcus didelphis is a poorly known bacterium that is associated with cutaneous lesions in opossums.10 A study identified the bacteria in nine opossums that had skin lesions. It is believed that skin lesions may have been the entry point for this agent in this case and the cause of the subsequent development of systemic lesions.10

Contributing Institution:

Departamento de Clínica e Cirurgia Veterinária

Escola de Veterinária

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

Av. Presidente Antônio Carlos,

Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. www.vet.ufmg.br

JPC Diagnoses:

1. Lung: Bronchopneumonia, catarrhal and lymphohistiocytic, multifocal, mild to moderate, with metastrongyle adults, larvae, and eggs.

2. Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, lymphohistiocytic and neutrophilic, diffuse, moderate.

JPC Comment:

Didelphostrongylus hayesi is an opossum lungworm with a wide distribution and high prevalence, above 70% in some studies, in opossums in the Americas.8 Oppossums become infected after ingesting intermediate hosts which, as the contributor notes, are terrestrial snails. The migratory path of the nematode larvae from the gut to the lung is unknown, but once in the lung, third-stage larvae mature into adults in the airways, particularly the intrapulmonary bronchi.8 Unlike other lungworms, which produce eggs that are deposited in host tissues or feces for futher development, D. hayesi produces eggs which hatch within their uteri.6 The hatched stage one larvae migrate up the trachea, are coughed up, swallowed, and then passed in the feces where they contaminate the environment and are ingested by their intermediate gastropod hosts.6

Typical gross lesions include lungs that do not collapse, focal to coalescing areas of emphysema, white to tan raised nodules on the pleural surface that roughly track the branching of intrapulmonary airways, and visible adult forms of D. hayesi on the visceral pleura.8 Histologically, D. hayesi shares many common characteristics with its metastrongyle brothers and sisters, to include a smooth cuticle, a pseudocoelom, an intestine composed of few multinucleated cells with an indistinct brush border, and coelomyarian musculature. In the United States, opossum lungs are frequently co-infected with D. hayesi and the capillarid nematode Eucoleus aerophilus.8

Discussion of this case centered initially on the histologic appearance of the lungworm itself, with some participants noting an apparent eosinophilic fluid within the pseudocoelom, typically a feature of spirurids. The moderator noted that this is commonly seen in wildlife nematode infections and speculated that this could be a degenerative change. Other participants noted that spirurids typically have, among other distinguishing features, prominent lateral cords, which are not present in the examined section.

Participants noted the rather dramatic smooth muscle hyperplasia within vascular walls throughought the section, the extent of which seems inconsistent with the small number of organisms in section. Other participants noted that a prominent smooth muscle layer is normal in the vasculature of some species, such as the cat, and that opossum control tissue would be helpful in determining if the vascular “lesions” are, in fact, pathologic.

Finally, participants discussed the thickened alveolar septa and prominent diffuse interstitial pneumonia, lesions which are not typically associated with lungworm infection. Participants reviewed the clinical history and speculated that the interstitial pneumonia was likely due to bacterial sepsis. This separate pathogenesis warranted two separate differential diagnosis, with the bronchopneumonia attributed to the metastrongyles and the interstitial pneumonia attributed to sepsis.

References:

- Bezerra-Santos MA, Ramos RAN, Cam-pos AK, Dantas-Torres F, Otranto D. Didelphis spp. opossums and their parasites in the Americas: A One Health perspective. Parasitol Res. 2021; 120:4091-4111.

- Caswell JL, Willians K. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. 2016;536-590.

- Costa LP, Astúa D, Brito D, Soriano P, Lew D. Didelphis albiventris (amended version of 2015 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021.

- Duncan RBJ, Reinemeyer CR, Funk RS. Fatal lungworm infection in a opossum. J Wildl Dis. 1989;25(2):266-269.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. American Registry of Pathology. Washington, DC;1999:27-29.

- Jones KD. Oppossum nematodiasis: diagnosis and treatment of stomach, intestine, and lung nematodes in the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana). J Exot Pet Med. 2013;22(4):375-382.

- Lamberski N, Reader JR, Cook LF, Johnson EM, Baker DG, Lowenstine LJ. A retrospective study of 11 cases of lungworm (Didelphostrongylus hayesi) infection in opossums (Didelphis virginiana). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2002;33(2):151-156.

- López-Crespo RA, López-Mayagoitia A, Ramírez-Romero R, Martinez-Burnes J, Prado-Rebolledo OF, Garcia-Marquez LJ. Pulmonary lesions caused by the lungworm (Didelphostrongylus hayesi) in the opossum (Didelphis virginiana) in Colima, Mexico. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2017;48(2):404-412.

- Prestwood AK. Didelphostrongylus hay-esi gen. et sp. n. (Metastrongyloidea: filaroididae) from the opossum, Didelphis marsupialis. J Parasitol. 1976;62 (2):272-275.

- Rurangirwa FR, Teitzel CA, Cui J, et al. Streptococcus didelphis sp. nov., a streptococcus with marked catalase activity isolated from opossums (Didelphis virginiana) with suppurative dermatitis and liver fibrosis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:759-765.