Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 23

15 April, 2020

CASE II: PV300 (JPC 4119013).

Signalment: A 6.9 years old, female spayed, mixed breed (canis familiaris).

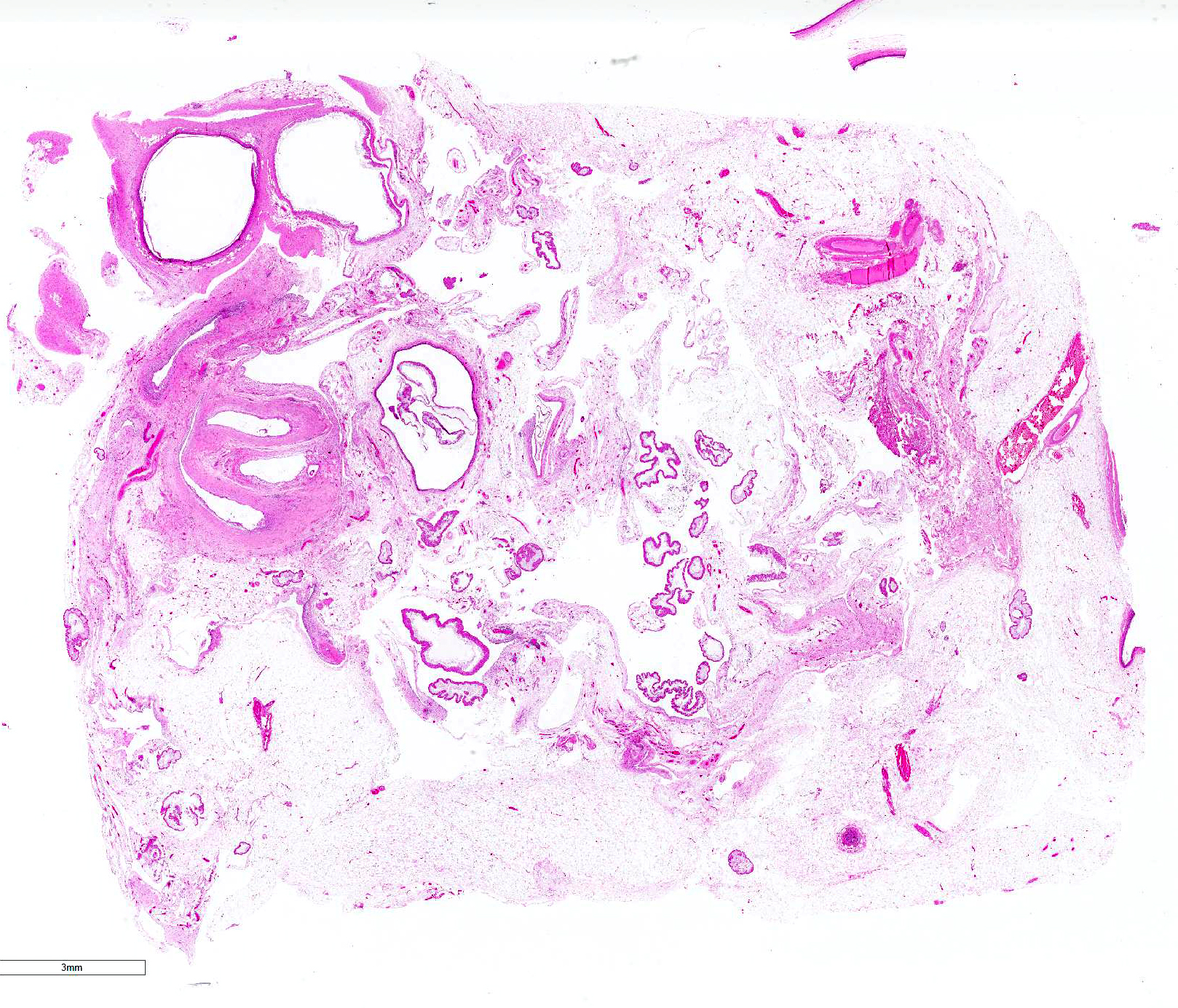

History: Ascites. Ultrasound examination revealed many cysts in the abdominal cavity. The cysts were sampled on exploratory laparotomy.

Gross Pathology: Open and friable cyst approximately 7 cm in diameter. On section many spaces, approximately 2 cm in diameter that contain clear fluid.

Laboratory results: NA.

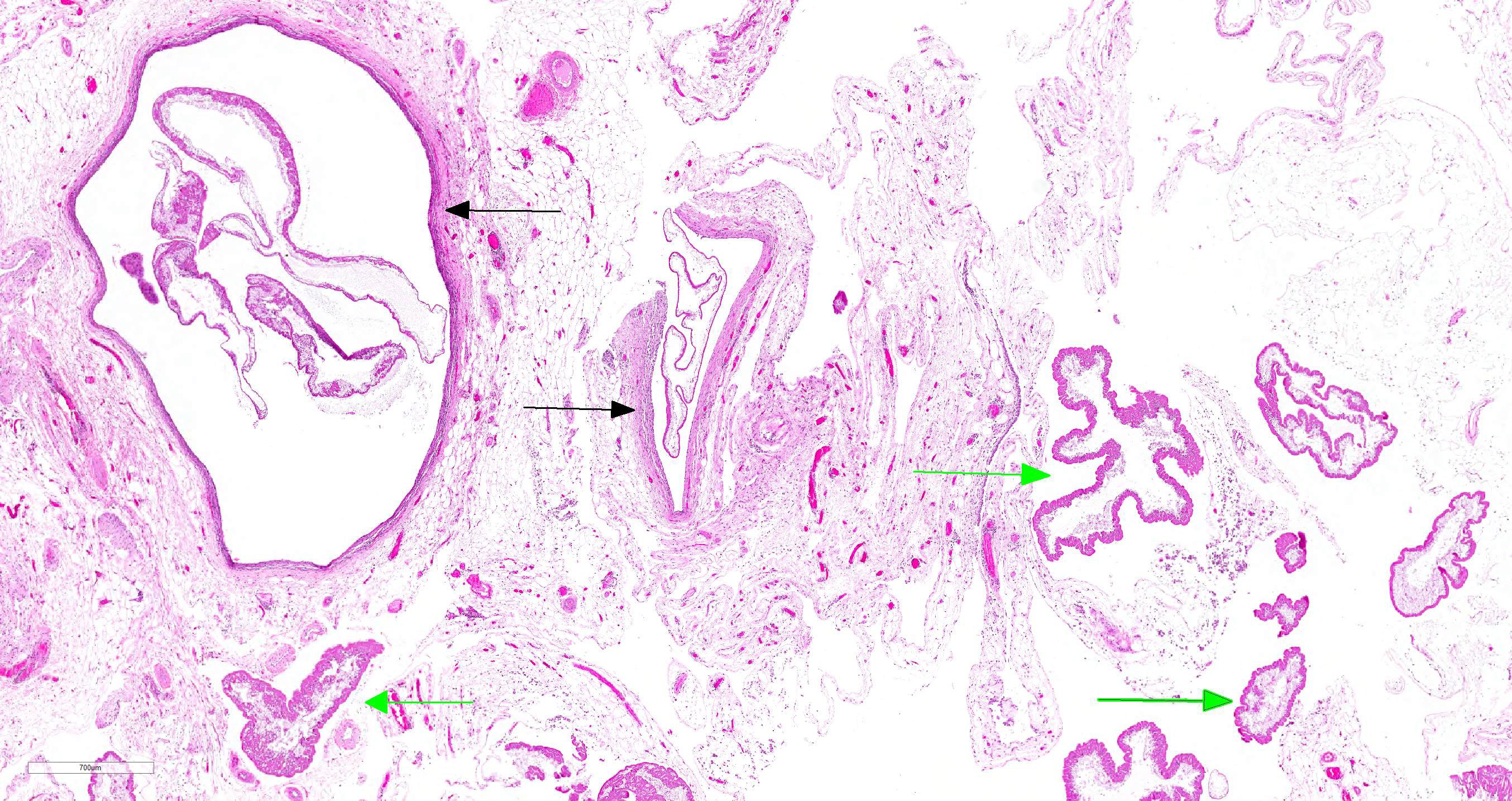

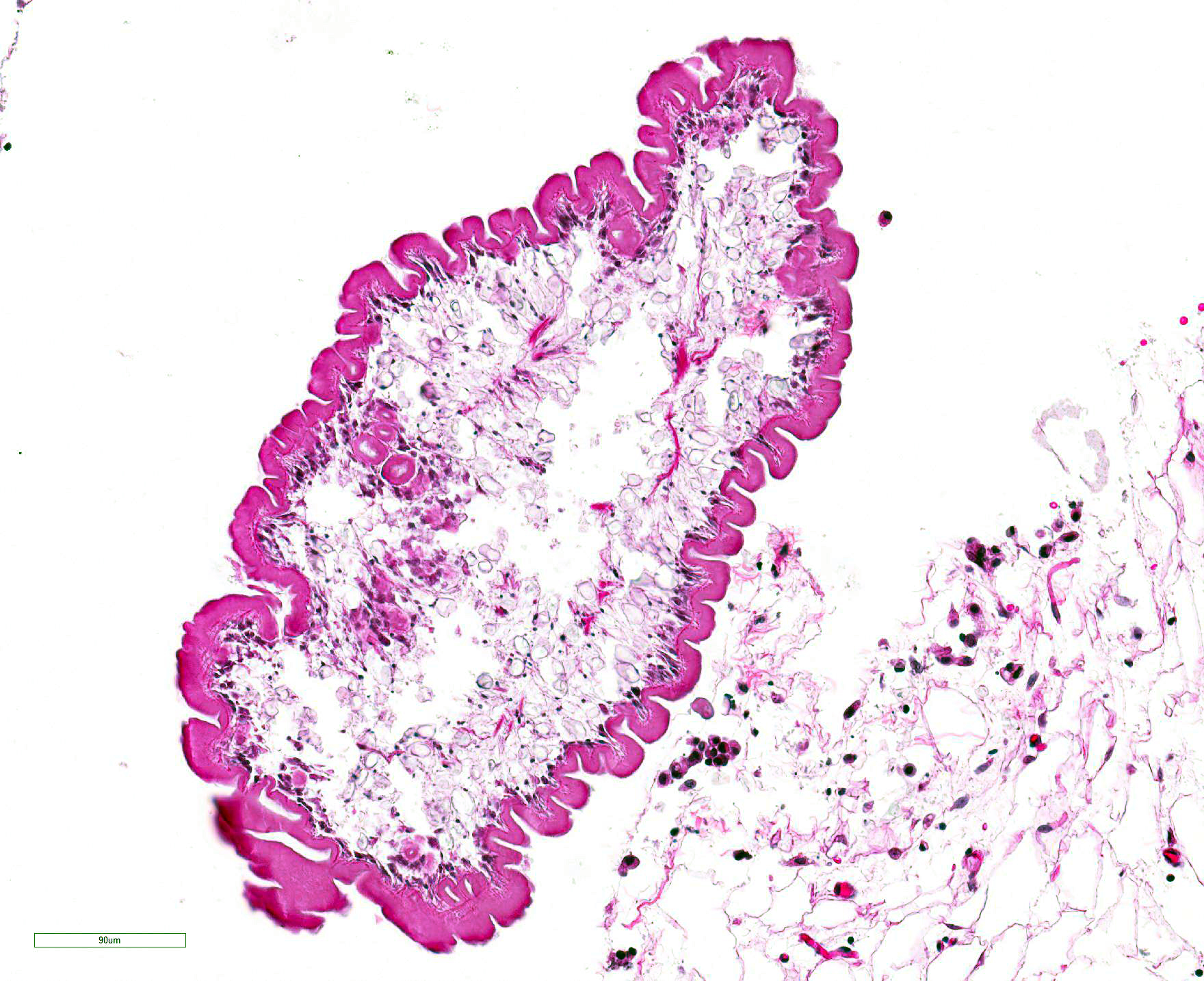

Microscopic Description: The tissue sections consist of mesenteric/peritoneal fat with peritoneal connective tissue with minimal fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. There is formation of many cystic spaces composed of a wall of mature fibrous tissue with an inner layer of palisading macrophages surrounding degenerate cestode larvae with a thick, smooth capsule, a subjacent layer of somatic cells and a loose body cavity with numerous calcareous corpuscles. No scolices are observed.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mild chronic peritonitis with cestode larvae - most compatible with canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis

Contributor Comment: Most parasites found in the peritoneal cavity occur during their normal migration to another site. Only a few larval and adult helminths use the abdominal cavity as their normal habitat. Cysticerci may be found on the peritoneum in rabbits and ruminants during their normal development; they are nonpathogenic and incite no tissue response beyond a thin bland fibrous capsule. Rarely, cysticerci are reported in the abdomen of carnivores, which are abnormal hosts.10

The etiology in this case is most compatible with infection with the tapeworm Mesocestoides spp. The larvae of Mesocestoides can proliferate extensively in the abdominal cavity of carnivores and cause a pyogranulomatous and proliferative peritonitis known as parasitic ascites or canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (CPLC).1,9,10The diagnosis in this case was confirmed by PCR. The differential diagnosis is infection with Spirometra spp. which may also encyst in the peritoneal cavity of carnivores.

Canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (CPLC) is an unusual parasitic disease in dogs that is caused by asexual proliferation of larval Mesocestoides. Mesocestoides spp. are tapeworm parasites. Adult worms reside in the intestinal tracts of their final hosts, which include carnivores, birds and occasionally humans. Infection with adult worms is usually asymptomatic. In contrast, the third stage larvae, called tetrathyridium, live in the serosal cavities of second intermediate hosts, which include amphibians, reptiles, birds, and rodents. Dogs and cats can also harbor tetrathyridia in their peritoneal cavities.6,9 Proglottids from adult parasites are not directly infectious to definitive or secondary intermediate host species.6,9

Diagnosis of infection by Mesocestoides spp. can be confirmed by morphologic identification of tetrathyridia or by PCR.

Recommended treatment involves long term therapy with praziquantel.8 Praziquantel has been reported effective to eliminate peritoneal tetrathyridia definitely. Early recognition of CPLC improves the prognosis, as it may be an incidental, but severe finding.8

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Resources

Weizmann Institute

Rehovot 76100, Israel

http://www.weizmann.ac.il/vet/

JPC Diagnosis: Mesentery: Encysted and free tetrythyridia, multiple with mild lymphohistiocytic peritonitis.

JPC Comment: The

uniqueness of the cyclophyllidean cestodes belonging to the Family

Mesocestoidae is matched only by the continued mystery of its life cycle. First

identified in 1863, published life cycles remain presumptive 150 years later.

Gravid proglottids are shed in the feces of a carnivore definitive host (which

is rarely man).2,7 Eggs are contained within the parauterine organ,

a structure unique to Meoscestoides and a diagnostic feature when

examining proglottids.7 Eggs lack a shell, and possess an

emybryophore enveloping the naked oncosphere.7 The eggs are

ingested by the first intermediate host (presumptively an arthropod) where it

develops into a second, as yet undescribed larval (or metacestode) stage. The

metacestode possesses all of the somatic structures of the eventual adult

cestode with the exception of reproductive organs. 7 The arthropod

host is then consumed by a vertebrate secondary host, usually an amphibian or

reptile (but rodents and birds may also serve as intermediate hosts), where

upon the larva passes through a series of post-larval forms, ultimately

becoming a tetrathyridia, the infective stage for the final carnivore host.2

Terrestrial carnivores includings dogs, cats, procyonids, mustelids, and

opossums, are most commonly identified as definitive hosts.2 While

in the secondary intermediate host or the definitive host, tetrathyridia posses

the ability to divide asexually, sometimes achieving large numbers and

infections similar to that illustrated in this case. Only in the definitive

carnivore host does the tetrathyridium evaginate, attach to the intestinal

mucosa, and mature into an adult cestode.2

Human infections with metacestodes are quite rare, and only two genera (M.

lineatum in Asia, Europe and Africa and M. variablilis in North

America) have been reported in these cases.4 Most cases involve the

consumption of uncooked viscera or blood containing metacestodes

(tetrathyridia).4

In the dog, the disease is referred to as canine peritoneal

larval cestodiasis, and this type of infection is less commonly seen in cats.1,3

Asexual proliferation of tetrathyridia results in variable degrees of granulomatous

peritonitis with occasional extension into abdominal organs and the thoracic

cavity. Clinical signs are generally vague, and include lethargy, weight loss,

vomiting, and ascites. Some cases are identified during routine OHE and

castration (including WSC 2014, Conference 3 Case 3.)1,3

In 2014, a similar asexually proliferative metacestode infection was first

identified in a captive juvenile Borneo orangutan which we had been American-born

and currently resided in a zoo in Michigan. Cestode parasites of the genus Versteria

are most commonly seen in small mammals including mustelids and weasels.

Atypical infection of this non-human primate manifested as cysts within the

liver, lung, and spleen containing numerous metacestodes which were identified

as unique members of the genus Versteria with 12% difference from the

DNA of the closest species (V. mustelae).5

References:

1. Boyce W et al. Survival analysis of dogs diagnosed with canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (Mesocestoides spp.). Vet Parasitol 2011. 180:256? 261

2. Centers for Diseases Control: DPDX ? Identifcation of Parasites of Public Health Concern. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/mesocestoidiasis/index.html

3. Crosbie PR, Boyce WM, Platzer EG. Diagnostic procedures and treatment of eleven dogs with peritoneal infections caused by Mesocestoides spp. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213:1578-1583.

4. Fuenza MV, Galan-puchdes MT, Maline JB. A new case report of human Mesocestoides infection in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 68(5)566-567.

5. Goldberg TL, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, Deering KM, Wallace RS, Clyde VL, Lauck M, Rosen GE, Bennett AJ, Greiner EC, O?Connor DH. Fatal metacestode infction in Bornean orangutan caused by unknown Versteria species. Emerg Inf Dis 2014; 20(1):109-113.

6. Kashiide T et al. Case report: First confirmed case of canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis caused by Mesocestoides vogae (syn. M. corti) in Japan. Vet Parasitol 2014. 20:154?157.

7. McAlister CT, Tkach VV, Conn DB. Morphological ad molecular characterization of post-larval pretetrathrydia of Mesocestoides sp. (Cestoda Cyclophyllida ) from Ground Skink from Southeastern Oklahoma. J Parasitol 2018; 104(1):246-253.

8. Papini R et al. Effectiveness of praziquantel for treatment of peritoneal larval cestodiasis in dogs: A case report. Vet Parasitol 2010. 170:158?16,

9. Uzal FA et al. Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Ed: M Grant Maxie. 6th ed. vol. 2, Elsevier, 2016:223.

10. Uzal FA et al. Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Ed: M Grant Maxie. 6th ed. vol. 2, Elsevier, 2016:255.

11. Wirtherle N et al. First case of canine peritoneal larval cestodosis causedby Mesocestoides lineatus in Germany. Parasitology International. 2007. 56:317?320