Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 9, Case 3

Signalment:

1 year and 11 months old, Mare, Standardbred Horse (Equus cabal/us)History:

Gross Pathology: The horse was in slightly poor body condition, with a mild generalized muscle atrophy and dull hair coat with multifocal alopecia, most evident on the ventral neck, abdomen and distal extremities. On closer inspection of the alopecic areas, there were abundant crusting, erosions and ulcerations of the skin, especially around the coronary bands and pastern on all four limbs. A moderate subcutaneous edema was evident on ventral abdomen and distal extremities. Free within the abdominal and thoracic cavity respectively, there were 2 liters of a straw-coloured transsudate. In the mucosa of the small intestine, large intestine and cecum, there were multifocal to coalescing, variably brownish coloured, round "button like" ulcers of approximately 0.5-4 cm in diameter, with elevated borders of firm consistency. The ulcers were often covered by light, dry, fibrinonecrotic material. There was also a diffuse, mild to moderate submucosal edema. In the non-glandular parts of stomach, there was severe hyperkeratosis. The liver was slightly decreased in size with a firm consistency, and on cut surface abundant fibrous streaks were evident, especially dissecting along bile ducts. The pancreas was moderately enlarged, firm in consistency and diffusely light in colour. Visceral and peripheral and lymph nodes varied from mildly to moderately enlarged, were slightly edematous, and varied in appearance; some showed distinct follicle formation and some were more homogenously light on cut surface. The bone marrow was light to dark red in colour.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

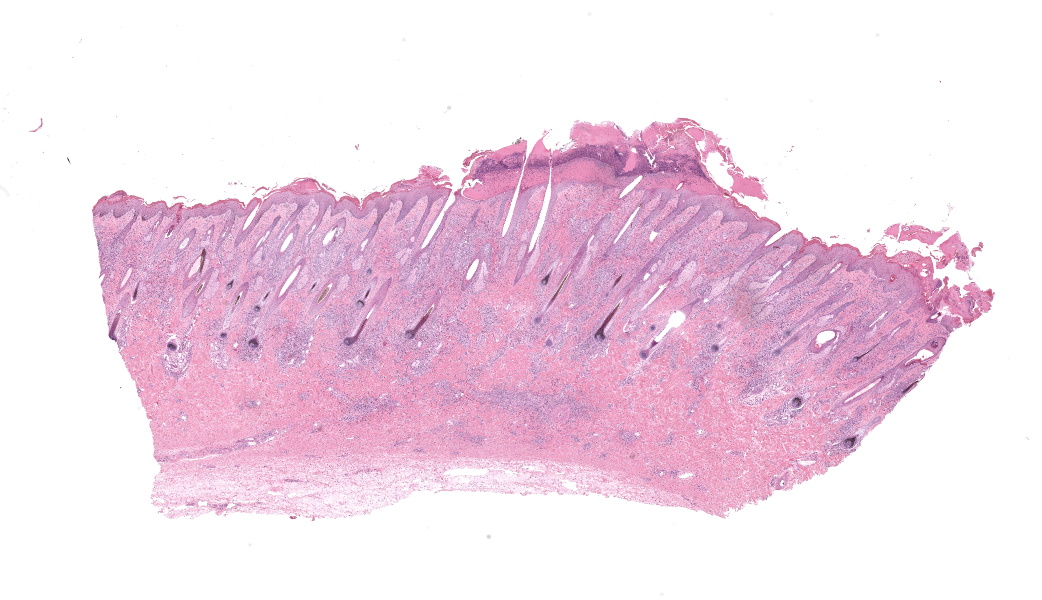

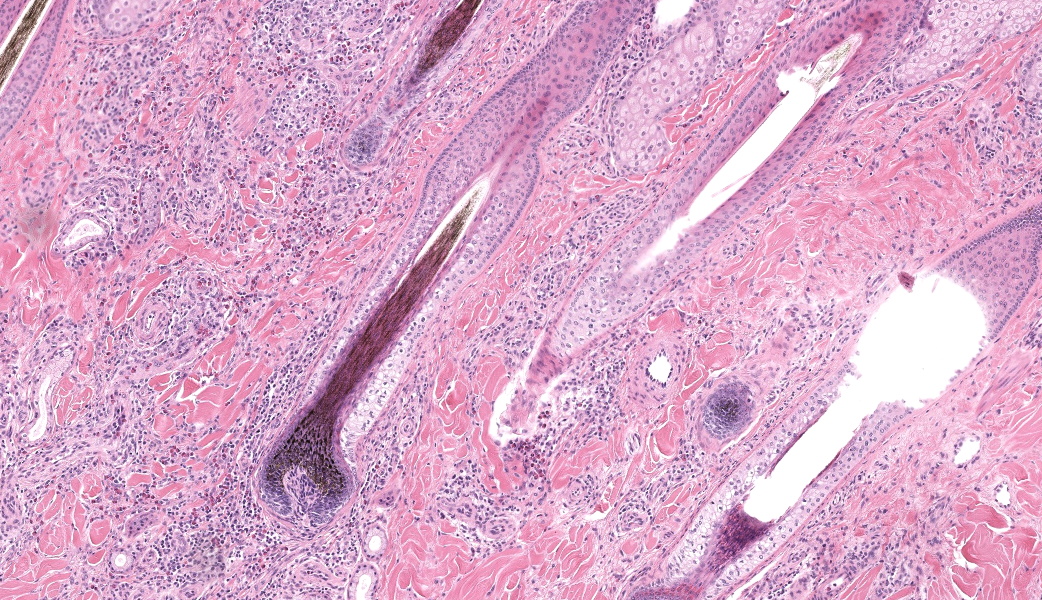

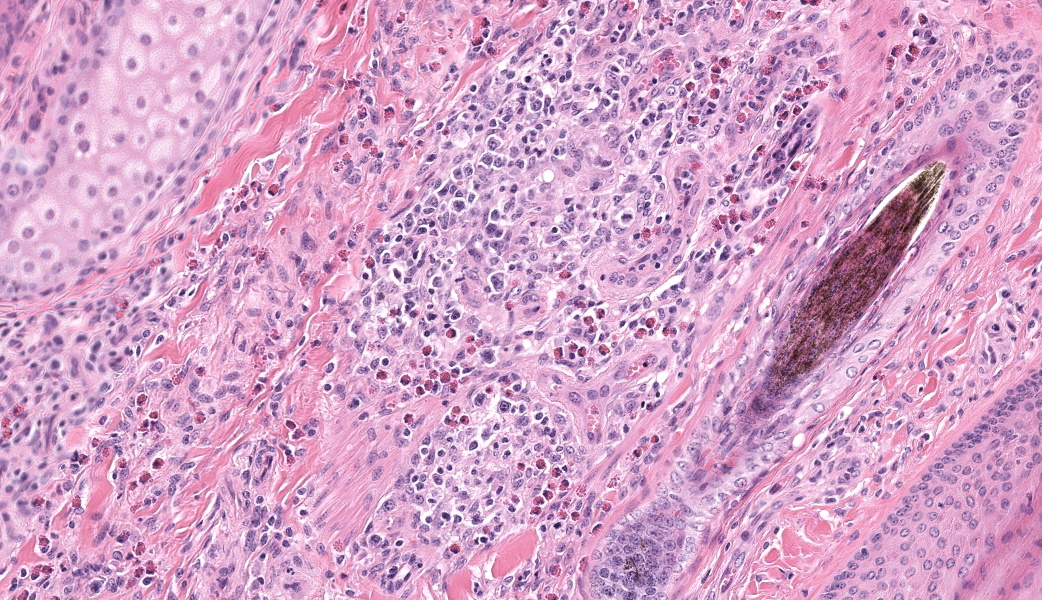

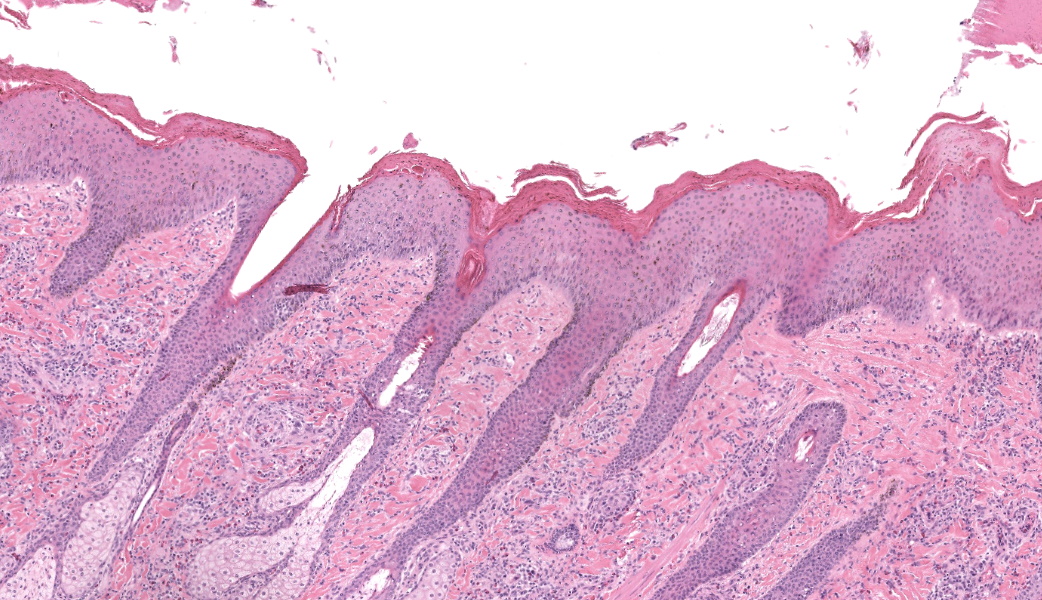

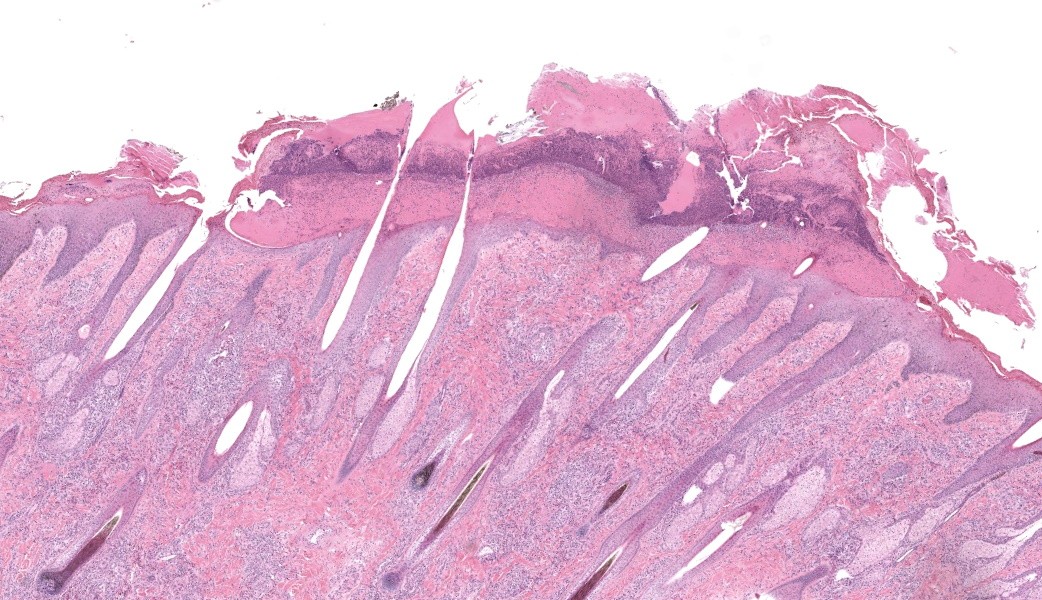

Haired skin, coronary band. Expanding and infiltrating the entire dermis are multifocal to coalescing perivascular, periadnexal and interstitial aggregates of moderate numbers of lymphocytes, eosinophils and histiocytes, fewer plasma cells and occasional neutrophils. Multifocally within dermis are few small areas of intensely eosinophilic, fragmented collagen fibers admixed with eosinophilic cellular- and basophilic nuclear debris, surrounded by epitheloid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells (eosinophilic granulomas). Intramurally and intraluminally within multiple hair follicles are moderate numbers of eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes and few multinucleated giant cells (mural and luminal folliculitis), and adjacent follicular epithelium display moderate spongiosis. In the dermal-epidermal interface, there is a multifocal mild edema. The epidermis shows mild lymphocytic infiltration, mild spongiosis and occasional apoptotic keratinocyte, diffuse mild acanthosis and mild rete ridge formation (epidermal hyperplasia), moderate parakeratotic and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and multifocal erosions and ulcerations, the latter being covered by large serocellular crusts spanning over several adnexal units. Serocellular crusts show abundant viable and degenerated neutrophils, occasional eosinophil, cellular debris, fibrin, free keratin and hair fragments and occasional small basophilic bacterial colonies. There are also small epidermal intracorneal pustules multifocally. Several arteriolar walls in deep dermis show infiltration of few eosinophils and lymphocytes (vasculitis). The deep dermis displays mild diffuse edema.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Haired skin, coronary band: Dermatitis and folliculitis, lymphoplasmacytic, histiocytic and eosinophilic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with eosinophilic granulomas, epidermal intracorneal pustules, serocellular crusts and orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosisEquine multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease (MEED)

Contributor's Comment:

Equine multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease (MEED) is a rare chronic disease and constitutes part of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in horses.13,15,17 MEED typically affects young Standardbred and Thoroughbred horses even though horses of older age and other breeds also may be affected.3,8,9,10,11,13,14,18,19,24 Seasonality with cases occurring in spring or summer is reported in some studies.11,14 Clinically, horses with MEED present with progressive weight loss, pitting edema, alopecia and exudative, exfoliative dermatitis characterized by scaling, crusting and skin ulcerations.3,6,10,11,13,14 Lesions often originate around coronary bands, sometimes with associated loss of chestnuts, and progressively becomes more generalized to also include head and the rest of the body.3,11,13,14 Most affected horses die or are euthanized within 8 months of diagnosis.13 In clinical cases described in the literature, pruritus is variably evident, as well as fever, diarrhea and peripheral eosinophilia.3,6,10,11,13,14,19 Peripheral eosinophilia is reported in approximately 14% of cases.3,13 Serum biochemical evidence of liver disease and/or hypoproteinemia may also be seen, and in a few cases, respiratory symptoms have been noted.3,6,8,9-11,18,19 In our case, there was no peripheral eosinophilia and no hypoproteinemia present at clinical work-up. Serum biochemistry was not investigated; hence, liver values were unknown.On postmortem examination, several organs are commonly affected in cases of MEED, including skin, pancreas, liver, common bile duct, gastrointestinal tract and lungs.13 Histologically, the disease is characterized by eosinophilic and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, sometimes with eosinophilic granuloma formation.13 In the skin, various inflammatory patterns have been reported in MEED, including perivascular, lichenoid interface, interstitial, diffuse, and granulomatous.13,14 Eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells are the main cellular elements.13,14 Other histological findings in the skin include epidermal hyperplasia, orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, epitheliotropic infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes, apoptotic keratinocytes, eosinophilic folliculitis, furunculosis, eosinophilic granulomas, and lymphoid nodules.13 Coagulated protein and collagen degeneration may be seen within deep dermal vessel walls.14 In our case, most of these lesions were present in examined sections of the skin. Within the gastrointestinal tract, lesions include ulcers on the tongue and/or within oral cavity, hyperkeratosis of the esophagus and non-glandular stomach, and mucosal ulcerations within the small and/or large intestine, as well as marked fibrosis in some organs, such as pancreas and liver; in the liver especially dissecting along bile ducts.11,14 Fibrosis may be so severe that loss of exocrine tissue is evident within pancreas, and in the liver, there may also be biliary hyperplasia.11,14 Lymph nodes may be enlarged due to eosinophilic infiltration, and increased numbers of eosinophils can be seen in bone marrow.6,9,13,14,18,19 In our case, all of these findings were present except oral ulcerations.

Cases of equine MEED has been reported since 1960's in Sweden, and was in 1985 described under the name of eosinophilic granulomatosis (EG).11 A case series was also reported from Canada the same year.14 Since then, various case reports of MEED have been published from around the world, including the US, Germany, Ireland, Belgium, Brazil, Italy and Spain.3,6,8,9,10,18,19,24 Systemic eosinophilic disorders, often referred to as hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), have also been described in other species, such as dogs, cats, ferrets, donkeys, and humans.4,5,7,16,20

The underlying cause of MEED is yet unknown.13 For equine IBD, a delayed hypersensitivity reaction has been proposed.15 For MEED specifically, recurrent type I hypersensitivity reactions caused by dietary, inhaled, or parasitic antigens have been suggested.11,13 In one recently published report, authors suggest that larval migrans seen in their case could have contributed to development of MEED.24 In our case, there was no evidence of ecto- or endoparasitism on either gross or histological examination. A genetic cause of MEED has been discussed, since Standardbreds and Thoroughbreds are over-represented in MEED cases.13 Another hypothesis is that clonal proliferation of T-lymphocytes trigger eosinophil proliferation through secretion of cytokines such as interleukin-5, which has been proposed as an underlying cause for

HES in humans.4 In the horse, MEED has been seen concurrently with intestinal T cell lymphoma, which may support this theory. Also in other species, such as the cat, dog and ferret, hypereosinophilic syndromes have been reported together with various T cell neoplasms. 1,2,9,12 In our case, there was no evidence of concurrent lymphoma.

Our case fits well with a diagnosis of MEED with regards to both clinical picture, gross findings, and histological findings. Differential diagnoses for lesions in the skin include autoimmune disorders, such as pemphigus foliaceus (PF), equine sarcoidosis, hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) intoxication, and insect bite hypersensitivity. PF presents with a similar clinical picture of crusting of the skin; however, on histopathological examination, consistent findings in PF patients are serocellular crusts or intraepidermal pustules and vesicles containing rafts of, or individualized, acantholytic cells, which were not seen in our case.13,22 In equine sarcoidosis, a nodular to diffuse lymphogranulomatous dermatitis with multinucleated giant cells and vasculitis is commonly seen.13 Hairy vetch toxicosis is mainly seen in cattle, but may also occur in horses.13 In horses, it is characterized by a nodular, granulomatous dermatitis. Eosinophilic infiltration may be seen in cattle with hairy vetch toxicosis but it is rarely seen in horses.13 Insect bite hypersensitivity, commonly caused by Culicoides spp in horses, is usually severely pruritic and presents as a superficial or superficial to deep perivascular dermatitis, dominated by eosinophils and lymphocytes. Eosinophilic folliculitis, erosions and ulcerations may also be seen as a result of self-trauma.13 Another differential diagnosis discussed for this case, mainly based on the ulcerative lesions within the intestine, was Rhodococcus hoagii infection. However, no pyogranulomatous lesions supporting Rhodococcus hoagii infection were present in the lymph nodes. Infection by Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica serovar typhimurium may as well give rise to button like ulcers within the large intestine, but taken all together, the combined clinical, gross and histological picture in this case supported a diagnosis of MEED.21

Contributing Institution:

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Biosciences, Section of Pathology Box 7023 SE 750 07, Uppsala, Swedenhttps://www.slu.se/enldepartments/Animal-Biosciencesf

JPC Diagnoses:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, perivascular, lymphohistiocytic and eosinophilic, chronic, moderate, with epidermal hyperplasia and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis.JPC Comment:

The contributor’s comment in this case provides an exceptional overview of multisystemic epitheliotropic eosinophilic disease (MEED) in horses and its major differentials, all of which were discussed during conference. MEED is currently considered to be an abnormal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in horses. The cutaneous manifestation of MEED classifies as a perivascular dermatitis pattern, and the depth of inflammation and affected vasculature can assist with the diagnosis of MEED compared to others that would be confined more to the superficial dermis (i.e. insect bite hypersensitivity). Conference participants ultimately all agreed with the contributor’s diagnosis of MEED in this case.If lesions are restricted to the GI tract, other causes of inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal parasitism, and idiopathic focal eosinophilic enteritis (IFEE) should rise higher on the differentials list. There was an excellent case of IFEE seen earlier this year in Conference 1, Case 3, the contributor of which provided a fantastic comparison between IFEE and MEED in their comment. Additionally, a thorough overview of eosinophils was covered in the JPC comment for Conference 2, Case 3 this year as well, and those two comments are great supplementals to this case.

As a quick refresher, the differentiation and maturation of eosinophils are dependent on expression and presence of certain transcription factors and cytokines, such as interleukin-5 (IL-5). IL-5 is the most important of these in eosinophil differentiation, maturation, and survival. As referenced by the contributor, there is a case report of MEED with concurrent GI lymphoma in a horse, contributing to the hypothesis that clonal expansion of T-lymphocytes may contribute to eosinophil proliferation via secretion of eosinophil-promoting cytokines, such as IL-5, in cases of hypereosinophilia seen in some lymphomas.4 Mature eosinophils contain granules that are full of cytotoxic compounds that are released in response to stimuli (i.e. certain infectious agents, allergens). Normally, T-helper type 2 (Th2) cells that are in proximity to the stressor produce high levels of IL-5, triggering eosinophil infiltration, activation, and subsequent release of additional cytokines, chemokines, and eosinophil granules. There is still substantial speculation on the cause(s) of MEED, but current literature suggests that it is likely a multifactorial, systemic presentation of a hypersensitivity reaction and that causes may vary between affected individuals, although parasites seem to be overrepresented in case reports.23

References:

- Barrs VR, Beatty JA, Mccandlish IA, Kipar, A. Hypereosinophilic paraneoplastic syndrome in a cat with intestinal T cell lymphosarcoma. J Small Anim Pract. 2002;43:401-405.

- Blomme EAG, Foy SH, Chappell KH, La Perle KMD. Hypereosinophilic syndrome with Hodgkin's-like lymphoma in a ferret. J Comp Pathol. 1999;120:211-217.

- Bosseler L, Verryken K, Bauwens C, et al. Equine multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease: A case report and review of literature. NZ Vet J. 2013;61 (3):177-182.

- Curtis C, Ogbogu P. Hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy lmmunol. 2016;50:240-251.

- Fox JG, Palley LS, Rose R. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with Splendore-Hoeppli material in the ferret (Mustela putoris furo). Vet Pathol. 1992;29:21-26.

- Gehlen H, Cehak A, Bag6 Z, Stadler P. Multisystemic eosinophilic disease in a Standardbred mare combined with generalized lymphadenitis. J Equine Vet Sci. 2003;23(5):216-219.

- Hendrick M. A spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes exemplified by six cats with eosinophilic enteritis. Vet Pathol. 1981; 18: 188-200.

- Horan EM, Metcalfe LVA, de Swarte M, Cahalan SD, Katz LM. Pulmonary and hepatic eosinophilic granulomas and epistaxis in a horse suggestive of multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease. Equine Vet Educ. 2013;25(12):607-613.

- La Perle KMD, Piercy RJ, Long JF, Blomme EAG. Multisystemic, eosinophilic, epitheliotropic disease with intestinal lymphosarcoma in a horse. Vet Pathol. 1998;35: 144-146.

- Laisse CJM, Castro do Nascimento L, Panziera W, et al. Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease in a horse in Brazil. Cienc Rural. 2017;47(5):e20160896.

- Lindberg R, Persson SGB, Jones B, Thoren-Tolling K, Ederoth M. Clinical and pathophysiological features of granulomatous enteritis and eosinophilic granulomatosis in the horse. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A. 1985;32:526-539.

- Marchetti V, Benetti C, Citi S, Taccini V. Paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia in a dog with intestinal T-cell lymphoma. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34:259-263.

- Mauldin EA., Peters-Kennedy J. lntegumentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers, Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016.

- Nimmo Wilkie JS, Yager JA, Nation PN, Clark EG, Townsend HGG, Baird JD. Chronic eosinophilic dermatitis: A manifestation of a multisystemic, eosinophilic, epitheliotropic disease in five horses. Vet Pathol. 1985;22:297-305.

- Olofsson KM. lmmunopathological aspects of equine inflammatory bowel disease. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; 2016.

- Paraschou G, Vogel PE, Lee AM, Trawford RF, Priestnall SL. Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease in three donkeys. J Comp Pathol. 2023;201:105-108.

- Schumacher J, Edwards JF, Cohen ND. Chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease of the horse. J Vet Intern Med. 2000; 14:258-265.

- Singh K, Holbrook TC, Gilliam LL, Cruz RJ, Duffy J, Confer AW. Severe pulmonary disease due to multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:189-193.

- Stucchi L, Lo Feudo CM, Valli C, et al. Equine multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease in two horses in Italy. Equine Vet Educ. 2022;34(10):413-417.

- Sykes JE, Weiss DJ, Buoen LC, Blauvelt MM, Hayden OW. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome in 3 Rottweilers. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:162-166.

- Uzal, FA., Plattner, BL., Hostetter, JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers, Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. Elsevier;2016.

- Vandenabeele SI, White SD, Affolter VK, Kass PH, Ihrke PJ. Pemphigus foliaceus in the horse: a retrospective study of 20 cases. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15:381-388.

- Villagrán CC, Vogt D, Gupta A, Fernández EA. Inflammatory bowel disease characterized by multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease (MEED) in a horse in Saskatchewan, Canada. Can Vet J. 2021;62(11):1190-1194.

- Vitale V, Troya-Portillo L, Corradini I, Serrano B, Armengou L. Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease subsequent to parasitic lymphadenopathy in a mare. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2023;11:e711.