Signalment:

Gross Description:

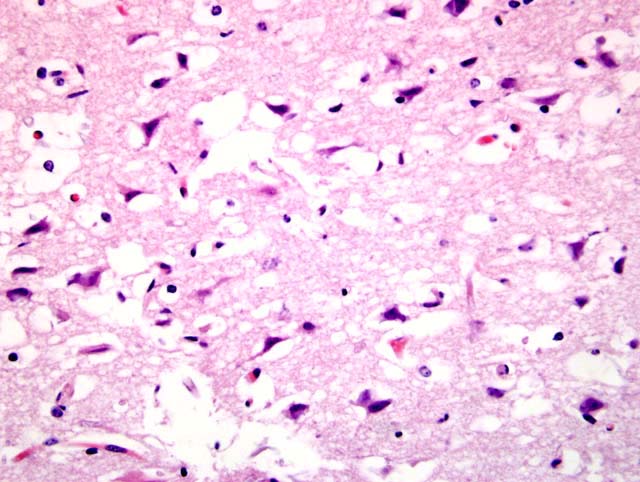

Histopathologic Description:

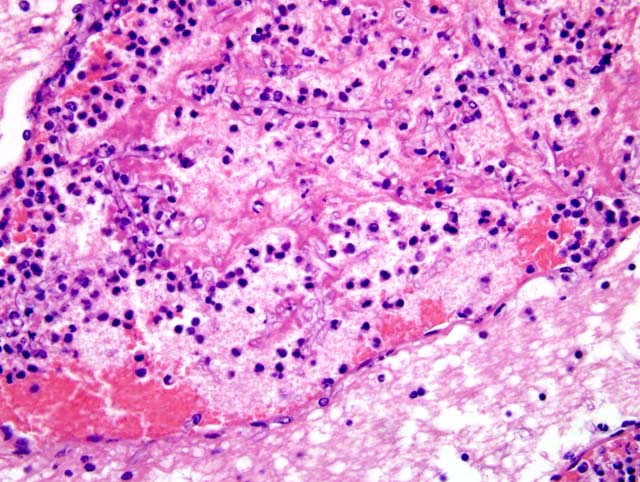

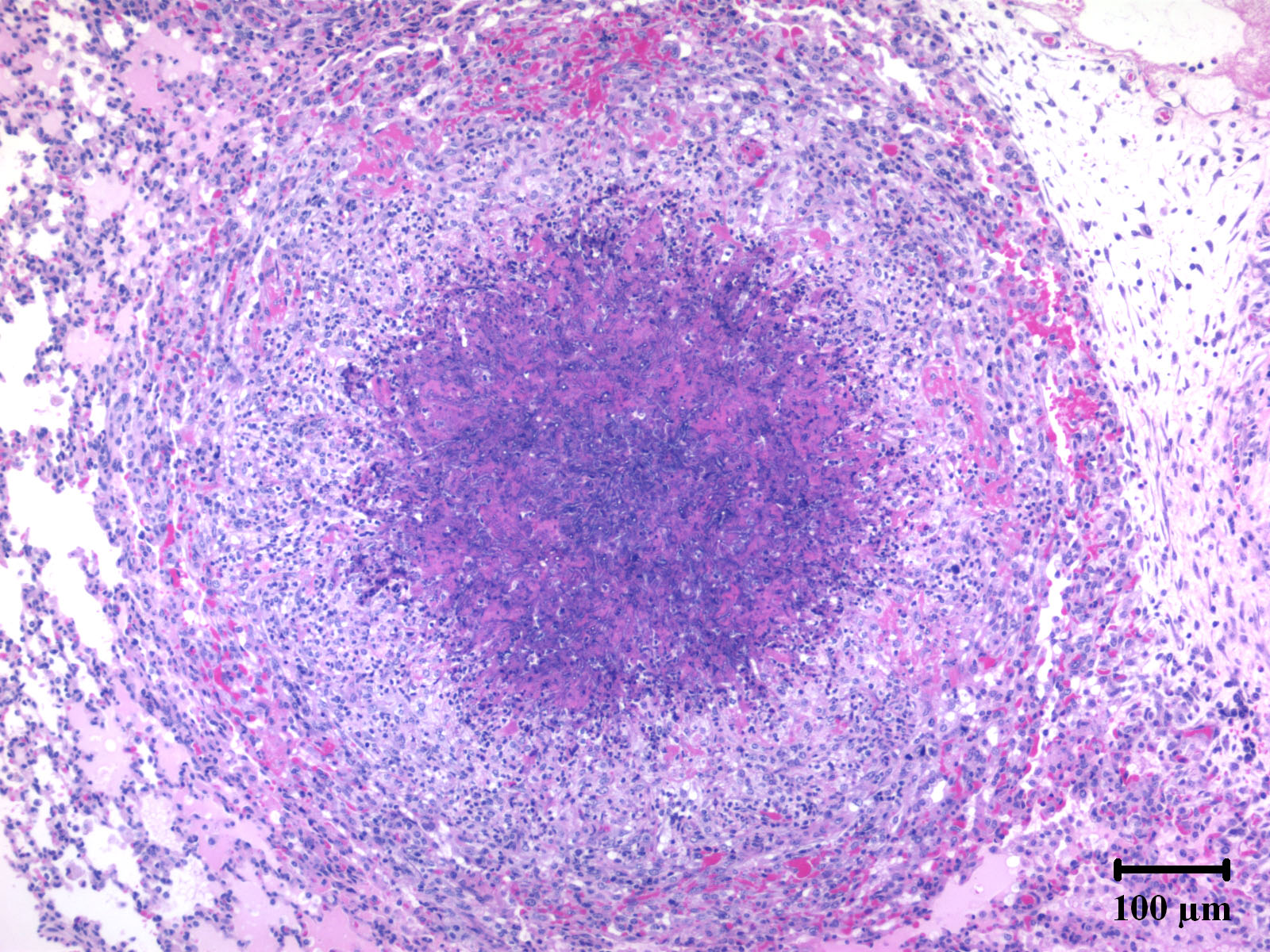

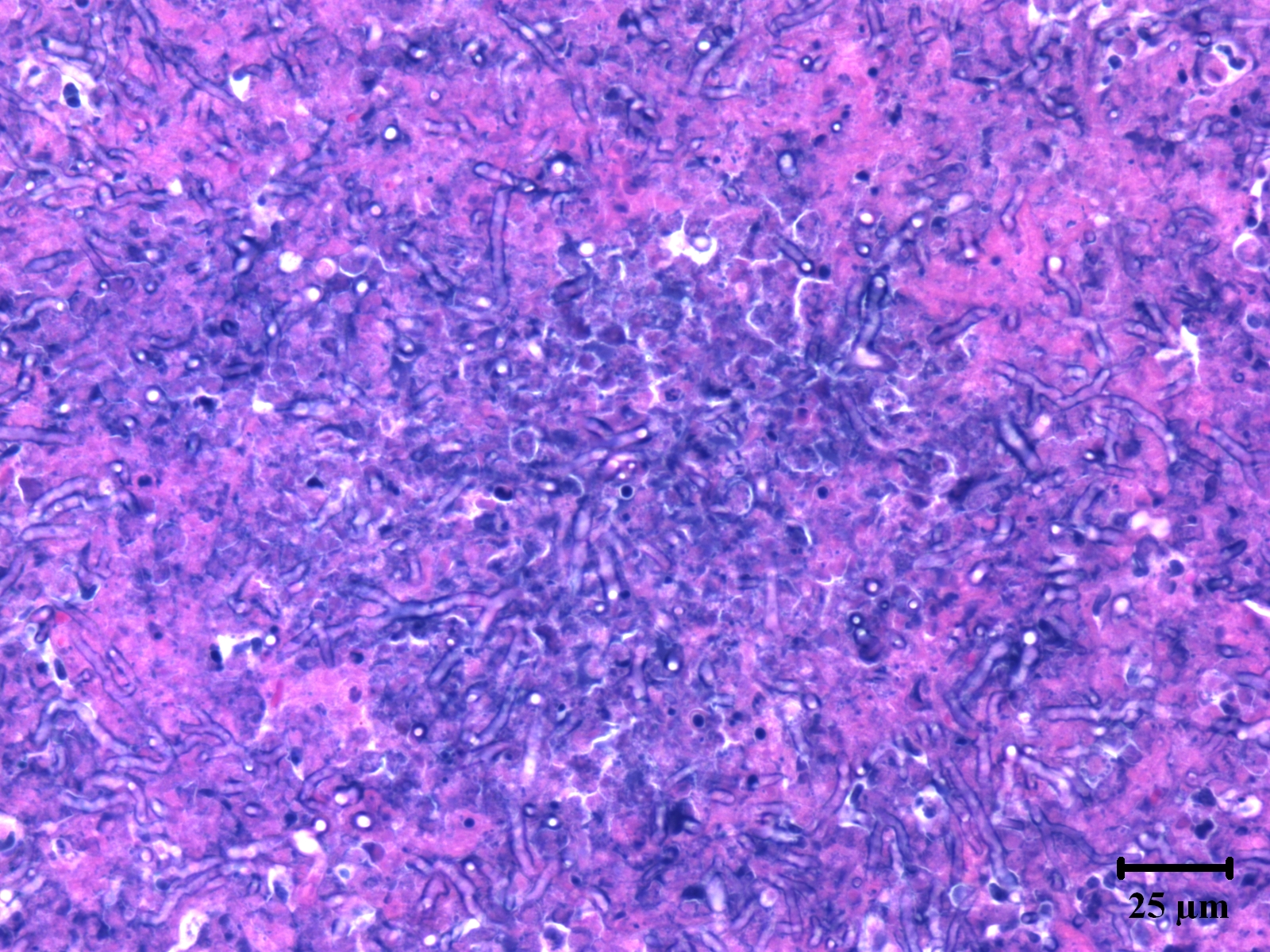

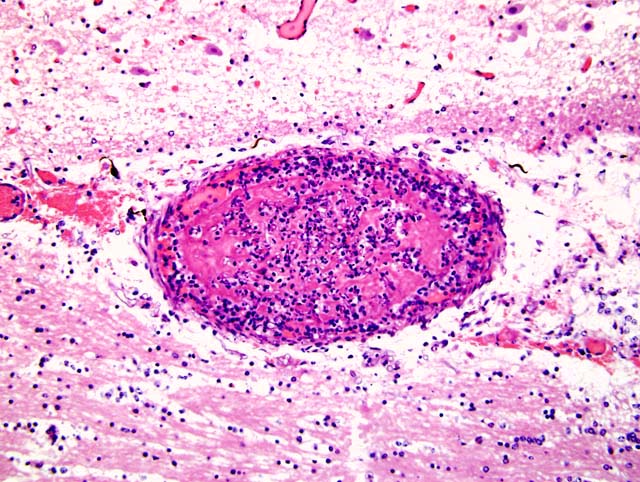

Within the lung (Fig. 2-2) (not submitted) are multifocal to coalescing nodular infiltrates (Fig. 2-3) of macrophages and lymphocytes surrounding cores of numerous neutrophils, necrotic debris and aggregates of fungal hyphae with morphology similar to that seen in the brain (Fig. 2-4) . Similar lesions were present in the kidney (not submitted).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Disseminated aspergillosis, due to A. fumigatus, with involvement of the lungs, brain and kidneys has been previously described in an adult white-tailed deer.10 Pulmonary aspergillosis has been reported in fallow deer (Dama dama) due to A. fumigatus and A. corymbifera.4 Disseminated aspergillosis is often associated with debilitation, immunologic suppression or prolonged antibiotic or corticosteroid administration. In the present case, debilitation, or prolonged use of antibiotics or corticosteroids were not factors; however, an unknown immunologic deficiency cannot be ruled out.

The two main portals of entry for fungal spores that cause systemic aspergillosis in cattle are the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Mycotic placentitis in cattle can lead to abortion. Systemic aspergillosis in 4-day-old calves where lesions included well developed hepatic granulomas with intralesional hyphae also suggests that a local or transitory mycotic placentitis could lead to calves that are born alive and survive.2 In mature cows it is suggested that the gastrointestinal tract is almost exclusively the portal of entry for A. fumigatus and that placentitis and pneumonia are secondary to hematogenous dissemination from the gastrointestinal lesions.8

The precise virulence factors of Aspergillus spp. are not well characterized. However, the common features of necrosis, angioinvasion and hematogenous dissemination may serve as clues to key factors in pathogenesis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Aspergillus sp. can produce several virulence factors including adhesins, antioxidants, enzymes, and toxins. The role of these virulence factors has not been fully defined. Restrictocin and mitogillin are two ribotoxins produced by Aspergillus that degrade host mRNA, thereby inhibiting host-cell protein synthesis. In addition, melanin pigment, mannitol, catalases, and superoxide dismutases are all antioxidant defenses produced by Aspergillus.7

Aspergillosis, primarily caused by A. fumigatus, is commonly encountered in birds.6,9 Captive penguins, turkeys, raptors and waterfowl appear to be particularly susceptible to infection. Certain physical and immunological characteristics of avians may make them more susceptible to infection. Birds lack an epiglottis to prevent particulate matter from being inhaled. Also, they are not able to produce a strong cough reflex due to their lack of a diaphragm. Avian heterophils use cationic proteins, hydrolases and lysosymes to kill fungal hyphae, which may be less effective than mammalian myeloperoxidase and oxidative destruction mechanisms. A unique feature of avian aspergillosis is the presence of reproductive phases of the fungus in tissue. This unique finding maybe due to the presence of cavernous air sacs, a warm core body temperature, or birds sensitivity to gliotoxin, which results in tissue necrosis and thus produces a nutrient rich environment for fungus growth.9

References:

2. Cordes DO, Royal WA, Shortridge EH: Systemic mycosis in neonatal calves. NZ Vet J 15:143-149, 1967

3 Emmons CW, Binford CH, Utz JP, Kwon-Chung KJ: Medical Mycology, 3rd ed, pp. 285-304. Lea & Febiger, London, Great Britain, 1977

4. Jensen HE, Jorgensen JB, Schonheyder H: Pulmonary mycosis in farmed deer: allergic zygomycosis and invasive aspergillosis. J Med Vet Mycol 27:329-334, 1989

6. Martin MP, Bouck KP, Helm J, Dykstra MJ, Wages DP, Barnes HJ: Disseminated Aspergillus flavus infection in broiler breeder pullets. Avian Dis 51:626-631, 2007

7. McAdam AJ, Sharpe AH: Infectious diseases. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Kumar V, Abbas, AK, Fausto N, 7th ed., pp. 399-400. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2005

8. Safarti J, Jensen HE, Latge JP: Route of infections in bovine aspergillosis. J Med Vet Mycol 34:379-383, 1996

9. Tell LA: Aspergillosis in mammals and birds: impact on veterinary medicine. Med Mycol Suppl 1:S71-S73, 2005

10. Wyand DS, Langheinrich K, Helmboldt CF: Aspergillosis and renal oxalosis in a white-tailed deer. J Wild Dis 7:52-56, 1971