Conference 16, Case 2

Signalment:

8-month-old, castrated male domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus)

History:

The cat was neutered and was recovering well until the evening following surgery. After then, the cat was inappetent and lethargic. He developed diarrhea the second day after surgery. The cat was found dead the third day after surgery.

Gross Pathology:

At postmortem examination, the cat was in good body condition with minimal postmortem decomposition. The skin of the scrotum, prepuce and perineum was swollen with large amounts of subcutaneous edema and emphysema. The right and left inguinal areas and medial aspect of the thighs were swollen by subcutaneous edema and emphysema, but the right rear leg was particularly swollen. The skin of the medial aspect of the thigh of the right rear leg was mottled red and green. The semitendinosus and semimembranosus muscles of the right and left rear legs were dark red to black, edematous and emphysematous with the most severe lesions in the right rear leg. There was marked subcutaneous edema consisting of light red fluid cloudy fluid in the skin of the dorsal lumbar area extending ventrally into the right and left flanks.

Laboratory Results:

Fluorescent antibody testing of the affected skeletal muscle was positive for Clostridium novyi and negative for Clostridium chauvoei, Clostridium septicum and Clostridium sordellii.

Moderate numbers of Clostridium novyi and rare Clostridium perfringens were isolated on anaerobic culture. There were no bacteria isolated on aerobic culture.

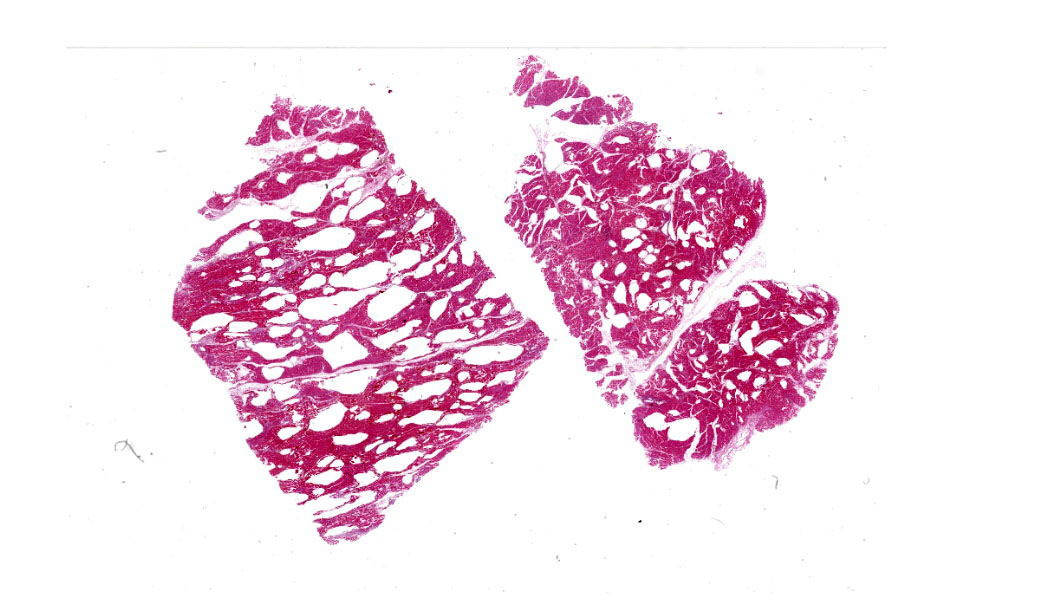

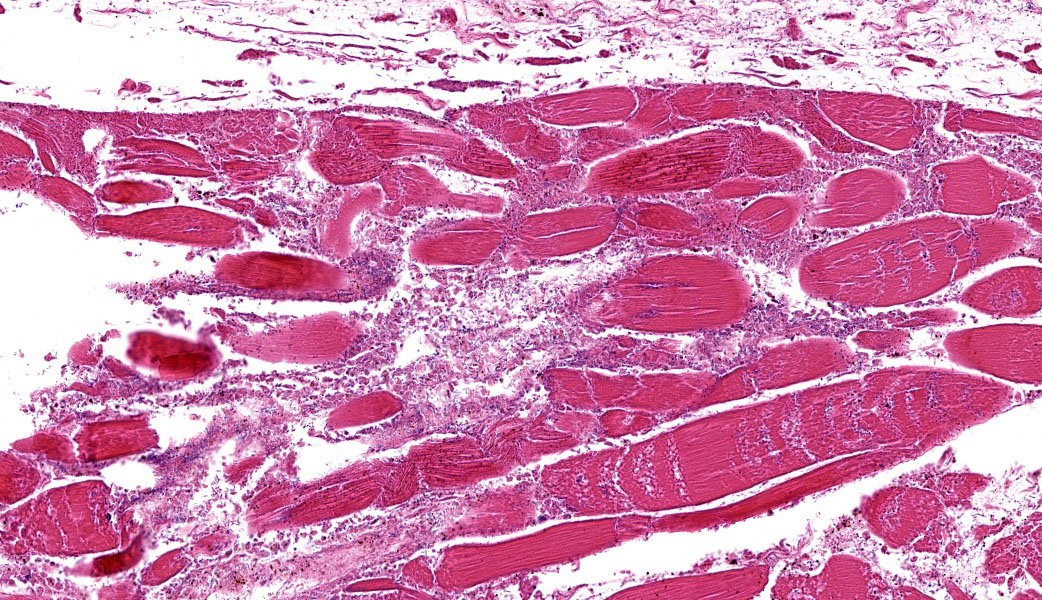

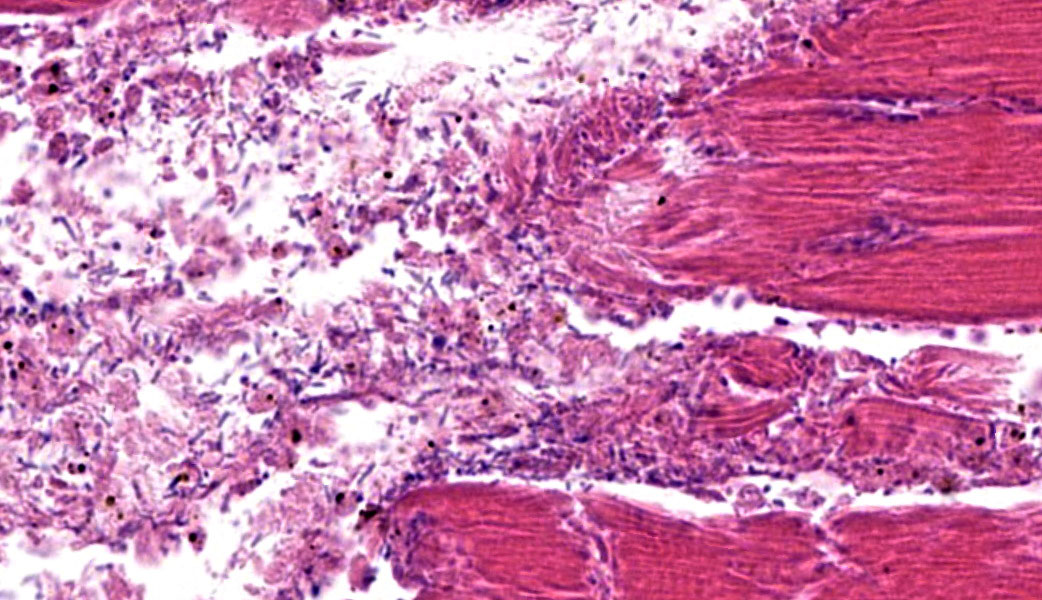

Microscopic Description:

The grossly affected skeletal muscle is necrotic with swollen, hypereosinophilic to pale staining myofibers that have lost their cross striations. The sarcoplasm of small numbers of myofibers is fragmented and replaced by eosinophilic flocculent material. The interstitium is emphysematous and contains small amounts of hemorrhage and edema that separate individual myofibers and the endomysium. There are also numerous large bacilli and a few perivascular to random multifocal infiltrates of small numbers of degenerate neutrophils in the interstitium. There are small numbers of arterioles and venules with necrosis of the vascular wall.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Skeletal muscle: Acute necrosis with emphysema, hemorrhage, mild suppurative myositis and numerous intralesional bacilli; etiology, Clostridium novyi.

Contributor’s Comment:

Clostridium species are large, gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria that produce endospores.4 They are obligate anaerobes with some species being difficult to grow (Clostridium novyi and C. haemolyticum) because they can rapidly die (within fifteen minutes) after being exposed to oxygen. The pathogenic Clostridium can be divided into three general groups based on the disease they cause. The neurotoxic clostridia include C. botulinum and C. tetani. The histotoxic clostridia include C. chauvoei, C. haemolyticum, C. novyi types A and B, C. perfringens type A, C. septicum and C. sordelli. The enteric clostridium include C. perfringens types A-E, C. difficile, C. spiroforme and C. colinum. Some authors will placed C. piliforme in a group by itself and classify it as an atypial clostridium. The histotoxic clostridia produce toxins, are invasive, and are responsible for the various forms of clostridial myonecrosis (clostridial myositis) such as malignant edema, gas gangrene, blackleg, and pseudoblackleg.2,5,6 Other than blackleg in ruminants being specifically caused by C. chauvoei, the other forms of clostridial myonecrosis are not specifically caused by any species of Clostridium. The clostridia causing myonecrosis are typically found in the soil or are part of the flora of the gastrointestinal tract. Clostridial myonecrosis can be the result of endogenous latent clostridial spores that reside in the skeletal muscle or exogenous bacteria that are introduced as wound contaminants. In both cases, the pathogenesis of myonecrosis is the same. Trauma to the skeletal muscle results in localized tissue hypoxia and anaerobic conditions allowing the clostridia to proliferate. As the pH and oxygen content of the traumatized skeletal muscle decreases, the conditions for clostridial growth and toxin production become ideal.

The clostridial toxins inhibit neutrophil infiltration into the lesion as well as weakening endothelial cell-to-cell contact. The clostridial toxin’s effects on endothelial cells can result in vascular thrombosis causing further tissue hypoxia and necrosis. The clostridial toxins are eventually absorbed systemically and can result in hypovolemia, cavitary effusion, low cardiac output, low cardiac contractility, shock and death.

In the submitted case, the histotoxic clostridium C. novyi was detected in the skeletal muscle by fluorescent antibody testing as well as being isolated from the affected skeletal muscle. Clostridium novyi has three types.2,4Clostridium novyi type A produces alpha toxin (a cytotoxin) and causes clostridial myonecrosis. Clostridium novyi type B produces both the cytotoxic alpha toxin and a beta toxin (a phospholipase). Clostridium novyi type B causes infectious necrotizing hepatitis (black disease) following liver fluke infections in ruminants. Clostridium novyi type C does not produce toxins and is not pathogenic. The C. novyi alpha toxin as well as four other large clostridial cytotoxins function by glucosylating cellular GTPase proteins.1,2 The clostridial cytotoxins have a particular affinity for the GTPase proteins that are involved in maintaining the cytoskeletal function. Inhibition of the cytoskeletal proteins results in loss of endothelial cell integrity that results in edema and thrombosis locally as well as hypovolemia, hypotension, organ failure and death systemically.

Clostridial myonecrosis can develop in multiple species, but is most common in ruminants, horses, and swine.3 In all species, skeletal muscle necrosis in the primary lesion. The muscle necrosis is accompanied by edema, hemorrhage, and often emphysema. The hemorrhage and lysis of erythrocytes cause the affected skeletal muscle to be dark red to black.

The necrotic skeletal muscle often has a rancid odor. The microscopic lesions mirror the gross lesions. The primary microscopic lesion is necrotic myofibers that are separated by edema, hemorrhage and lysed erythrocytes. The skeletal muscle may be emphysematous. There typically are very few neutrophils within the lesion. The number of bacteria in the lesion varies widely with the lesions in some animals containing large numbers of bacteria with the lesions in other animals containing small numbers of bacteria. Most lesions have small numbers of bacteria. Fragmentation of the necrotic myofibers in the deeper aspects of the lesions may be present. The affected animals die quickly usually within twenty-four hours if not treated. The histotoxic clostridia spread quickly throughout the carcass postmortem resulting in rapid decomposition. Because these bacteria spread quickly throughout the carcass postmortem, one has to be careful in interpreting positive identification of histotoxic clostridia within muscle lesions as the Clostridium species identified may be a postmortem contaminant rather than the cause of the muscle necrosis.

Contributing Institution:

New Mexico Department of Agriculture

Veterinary Diagnostic Services http://www.nmda.nmsu.edu/home/divisions/vds/

JPC Diagnoses:

Skeletal muscle: Myositis, necrotizing, acute, diffuse, severe, with emphysema and large, occasionally sporulating bacilli.

JPC Comment:

This contributor’s outstanding comment pretty much covers it all! The few points from the conference discussion not covered in the write-up above focused on a review of some of the terminology utilized to describe degenerative and necrotic lesions in skeletal muscle (“loss of cross striations,” “vacuolation,” “fragmentation,” “myofibrillolysis,” “contraction bands”, etc.). Contraction bands, in particular, take some practice to see on an H&E and are characterized by hypercontracted, intensely eosinophilic transverse bands within the sarcoplasm of myocytes. These represent focal myofibrillar disruption and are often seen in rhabdomyolysis, trauma, or ischemia.7 They correspond to extremely shortened sarcomeres with obliterated I-bands and H-zones and are an indication of myocyte necrosis.7 The contraction bands in these cases can be beautifully revealed with a PTAH stain. For both written and oral descriptions of slides in which a clostridial organism is suspected, Dr. Uzal additionally made a point to mention that there should be mention of whether the bacteria are sporulating or non-sporulating. In this case, there were a few sporulating bacteria present on the H&E; this is reflected in the JPC’s morphologic diagnosis.

Dr. Uzal ran immunohistochemical stains on this case for multiple gas gangrene-causing clostridial species in his lab, as gas gangrene cases are frequently infected with multiple organisms. In this case, there was immunoreactivity for both Clostridium novyi and Paraclostridium sordellii (previously C. sordellii). Of the types of C. novyi listed by the contributor, type A was most likely the offender in this case. The Type A toxin of C. novyi behaves similarly to the A-B toxin of C. difficile discussed above in Case 1. Participants also took note that C. perfringens had been cultured by the contributor and speculated that the C. perfringens were present as bystanders and were not actively contributing to the infection in this cat.

References:

- Aronoff DM. Clostridium novyi, sordellii, and tetani: mechanisms of disease. Anaerobe. 2013;24:98-101.

- Aronoff DM and Kazanjian PH. Historical and contemporary features of infections due to Clostridium novyi. Anaerobe. 2018;50:80-84.

- Cooper BJ and Valentine BA. Muscle and tendon. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th vol. 1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:230-233.

- Markey BK, Leonard FC, Archambault M, Cullinane A, Maguire D. Clostridium species. In: Markey BK, Leonard FC, Archambault M, Cullinane A, Maguire D, eds. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology. 2nd St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2013:215-229.

- Nagahama M, Takehara M, Rood JL. Histotoxic clostridial infections. Microbiol Spectrum. 2019;6(4):1-17.

- Stevens DL, Aldape MJ, Bryant AE. Life-threatening clostridial infections. Anaerobe. 2012;18:254-259.

- Venance SL, Burns KL, Veinot JP, Walley VM. Contraction bands in visceral and vascular smooth muscle. Hum Pathol. 1996;27(10):1035-1041.