Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 12

11 December 2019

CASE IV: L19-3350 (JPC 4135947). Tissue from a rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus).

Signalment: 7-year-old, intact female, Flemish giant domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

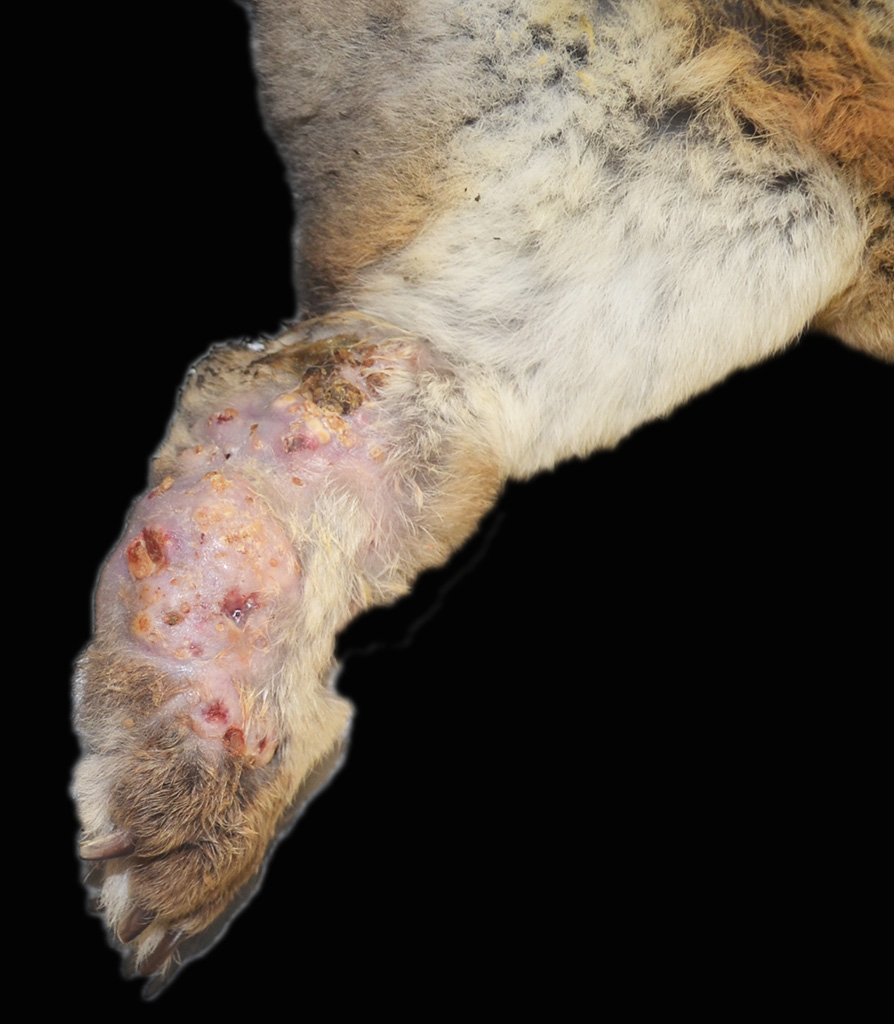

History: The rabbit presented with a 1-month history of severe subcutaneous swelling, erythema, ulceration and abscess formation of the left hindlimb extending from the hock to the digits. A focal area of mild subcutaneous swelling was also noted on the plantar surface of the right hindlimb metatarsal area with a similar exudate on cut surface. The animal was housed on a wire cage outdoors with no bedding. Decreased borborygmi were noted on auscultation and the haircoat in the perineal region was stained with feces. Due to the severity of the lesions, which would require limb amputation, euthanasia was elected.

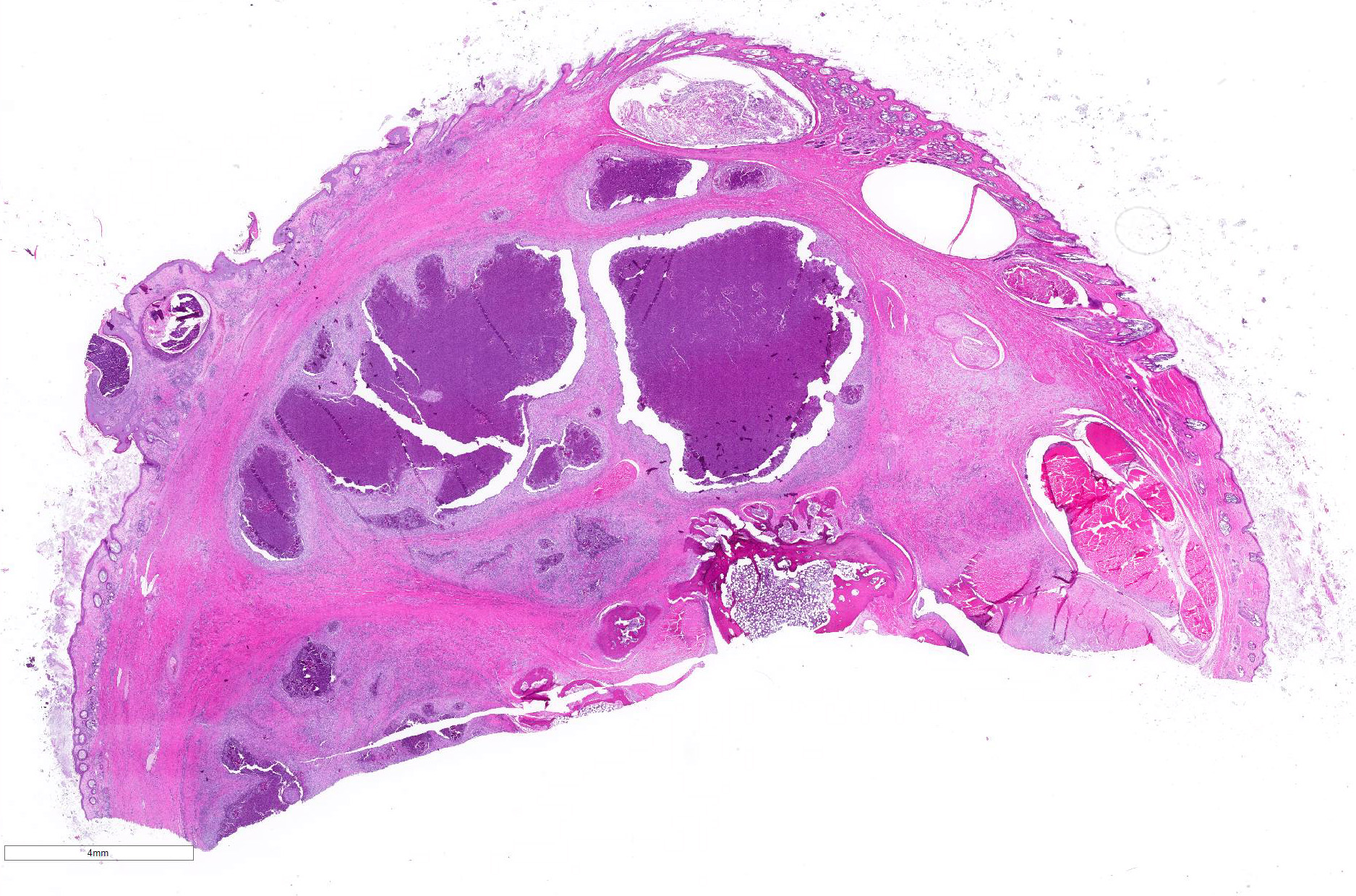

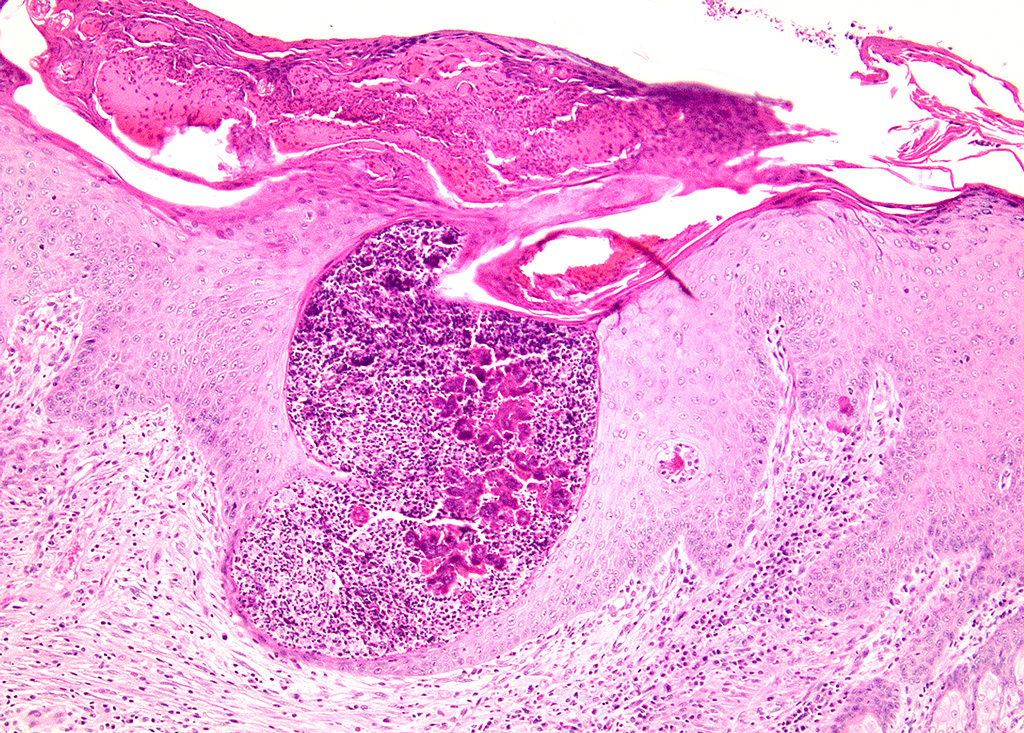

Gross Pathology: The left metatarsal region is markedly swollen, with multifocal ulceration and fistulous tracts that extend to the plantar surface of the paw (Figure 1). On cut surface, the subcutis is effaced by multifocal abscesses containing abundant, inspissated, white to pale yellow, granular exudate extending to the periosteum of the underlying metatarsal and phalangeal bones (Figure 2). The distal right metatarsal region has a 0.5 cm diameter focal abscess within the subcutis.

Laboratory results: Bacteriology: Skin ? Moderate growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Microscopic Description:

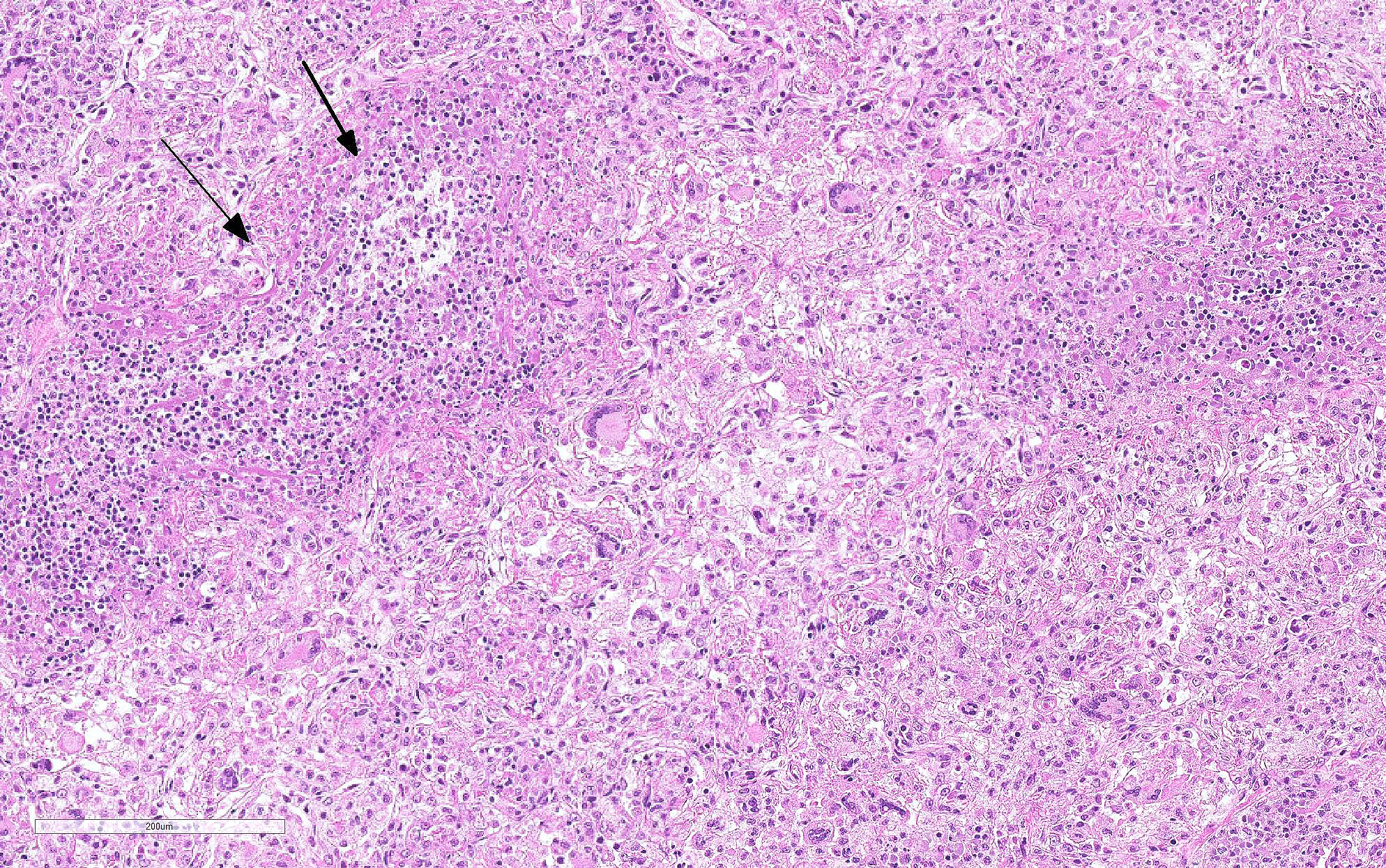

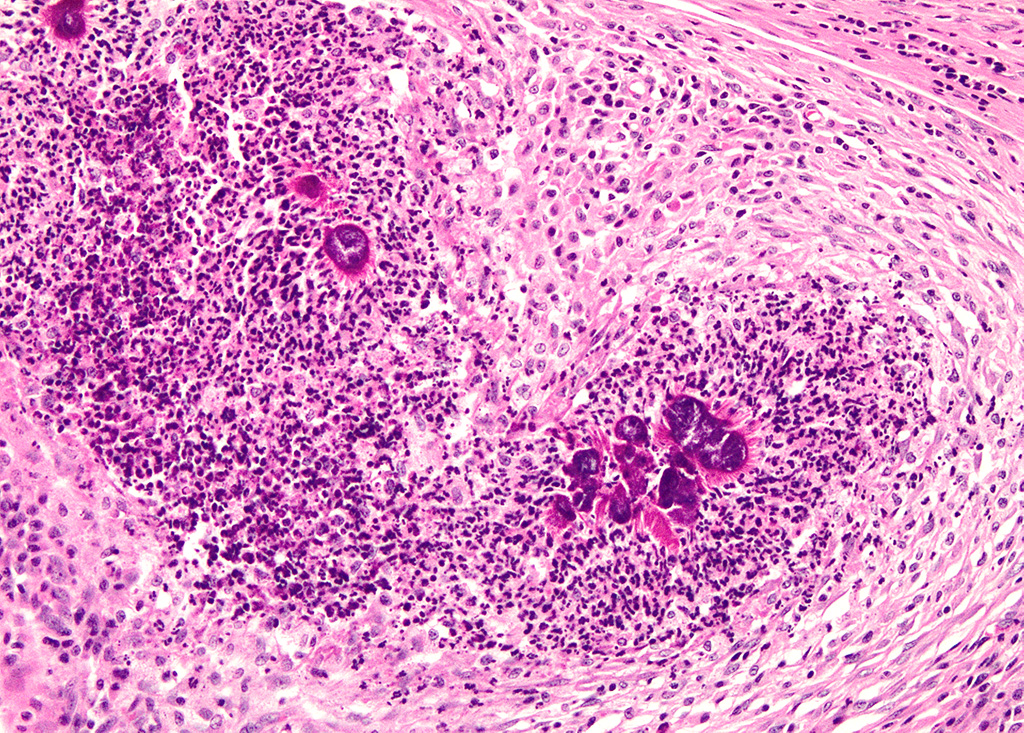

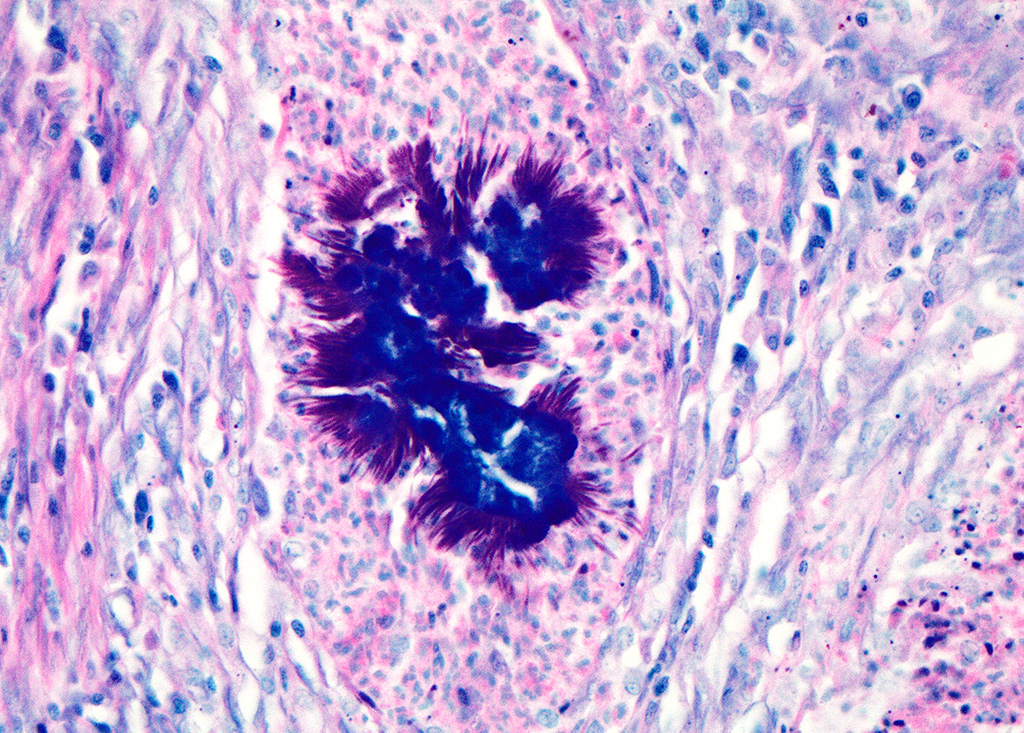

Haired skin (left distal hindlimb): The dermis and panniculus are effaced by multifocal to coalescing areas of liquefactive necrosis characterized by abundant hypereosinophilic cellular debris, hemorrhage, numerous heterophils and intralesional colonies of coccobacillary bacteria surrounded by abundant intensely eosinophilic (hyalinized) material frequently forming radiating, club-like projections (Splendore-Hoeppli reaction) (Figure 3). The areas of necrosis are peripherally delimited by abundant foamy histiocytes and proliferation of dense fibrous connective tissue. There are occasional dilated lymphatic vessels. The cortical bone of the metatarsal and phalangeal bones represented in the sections have variable areas of periosteal bone proliferation and occasional Howship?s lacunae containing osteoclasts. Other histologic changes variably represented in the sections include proliferation of the synovial membrane within tendon sheaths along with moderate infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells; skeletal muscle atrophy, regeneration and replacement by fibrous connective tissue characterized by shrunken myofibers, multinucleated myocytes and moderate endomysial infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells; and peripheral nerve fiber degeneration and loss characterized by marked vacuolization and deposition of mucinous matrix and/or fibrous connective tissue within the endoneurium. Histologic changes within the epidermis and adnexa are also variably represented in the sections. The epidermis is markedly hyperplastic with occasional pustules and crusts, and multifocal transepidermal elimination of necrotic debris and bacterial colonies into the epidermal surface or into the lumen of hair follicles is also noted (Figure 4). Multiple hair follicles are markedly dilated and filled with abundant keratin (comedone), and the adnexa are frequently delimited by moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Special stains performed (Gram, Gridley, Giemsa, Steiner, and Fite?s) characterized bacterial colonies as being composed by short rod-shaped gram-negative bacteria that also stain strongly basophilic with Giemsa (Figures 5 and 6). No fungal organisms, spirochetes or acid-fast bacteria were identified.

Additional histologic findings (not represented in the sections) include marked myeloid hyperplasia with a left shift, mild to marked extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver and spleen, and abundant intravascular heterophils within pulmonary capillaries and larger vessels.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Skin (left distal hindlimb): Dermatitis and panniculitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with abundant large intralesional gram-negative bacterial colonies and Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.

Contributor Comment: Botryomycosis, also known as bacterial pseudomycetoma, is a term that commonly refers to a chronic bacterial infection of the skin and subcutis caused by non-filamentous bacteria that tend to form grossly visible colonies as tissue grains within the lesions (noted in this case as a granular exudate).11 This condition affects multiple animal species including equids, cattle, dogs, hamsters, mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs.1-6,9,12,14-16 It has to be differentiated from actinomycotic and eumycotic mycetomas, which usually present with similar gross and histologic lesions. Actinomycotic mycetomas are frequently associated with subcutaneous Actinomyces spp. or Nocardia spp. infections, which can be differentiated histologically using special stains including Gram and modified acid-fast: Actinomyces spp. are gram-positive, non-acid-fast, filamentous bacteria, and Nocardia spp. are gram-positive and variably acid-fast filamentous bacteria. Eumycotic mycetomas are caused by a variety of fungi that can be readily identified using stains such as methenamine silver.

Botryomycotic lesions usually develop in the skin and subcutis, but frequently extend deeply, affecting the underlying muscle and bone. Visceral lesions are uncommon but have been reported in multiple species as well.2,4,15 Grossly, lesions are characterized by firm, focal to multifocal nodules containing a white to yellow exudate with a gritty texture (tissue grains) that tend to ulcerate and/or develop fistulous tracts as observed in this case. Additional histologic findings in this rabbit included marked myeloid hyperplasia with a left shift, mild to marked extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver and spleen, and abundant intravascular heterophils within pulmonary capillaries and larger vessels; all of these most likely related to the inflammatory response secondary to the infection.

The Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon has been reported as a classic histologic feature of botryomycosis. Although its composition is not fully characterized, it is reportedly composed of necrotic debris and deposition of immune complexes.8 While in some cases deposition of immunoglobulins was observed via immunohistochemistry and immunoelectron microscopy, in other instances this material may be composed of eosinophilic major basic protein.8,13 Differences in composition may be associated with the specific causative agent and probably other factors such as disease stage and previous treatments.8

Even though the pathogenesis of botryomycosis is not well understood, it is believed that the pyogranulomatous inflammation develops as a consequence of the complex interactions between the host response and the agent?s virulence factors. It is speculated that the inability to clear the infection may be associated with a polysaccharide coating synthesized by the bacteria. Coagulase-positive staphylococci (mainly S. aureus) are the most common causative agents of botryomycosis, but other bacteria including Pseudomonas spp., Streptococcus spp., Actinobacillus spp., Pasteurella spp., Proteus spp., Escherichia coli, Trueperella spp. and Bibersteinia spp. have also been identified. This condition is generally secondary to wound contamination or traumatic lesions; in this case it was likely associated with poor housing conditions with no bedding. Usually, the bacteria are not well recognizable on H&E sections, in which special stains can aid in ruling out actinomycotic bacteria (actinomycotic mycetoma) and fungi (eumycotic mycetoma). Bacterial and/or fungal culture is required in order to confirm the etiologic agent. In this case, bacterial colonies were gram negative and basophilic with a Giemsa stain, consistent with the culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The Gram and Giemsa stains highlighted the radiating, club-like projections within the Splendore-Hoeppli material.

Contributing Institution:

Louisiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (LADDL), School of Veterinary Medicine, Louisiana State University (http://www1.vetmed.lsu.edu/laddl/index.html)

JPC Diagnosis: Partial cross section of leg: Dermatitis and cellulitis, pyogranulomatous (heterophilic and granulomatous), multifocal to coalescing, severe, with Splendore-Hoeppli material and numerous bacilli.

JPC

Comment: The

contributor has provided an excellent review of the condition of botryomycosis,

a unique histologic lesion that may be seen in a variety of species and

tissues, and results from several common bacterial genera as mentioned by the

contributor. It should be stressed that while Splendore-Hoeppli material, which

may be composed of immunoglobulins, major basic protein, or both, is a

component of botryomycotic lesions, it may be seen in a number of other lesions

other than botryomycosis, including many fungal and helminth infections, as

well as surrounding a variety of inert materials within the skin and subcutis.8

Pseudomonas aeuginosa is a ubiquitous gram-negative organisms of soil

and aquatic environments, which, as a result of it intrinsic and expanding

antibiotic resistance, is a particulary worrisome opportunistic wound invader.

It is a common opportunist in hospital settings, and the second most common

isolate in ventilator-related infection.5

P. aeruginosa is a potent infectious agent in acute infections (with a

host of virulence factors) and chronic infections (which are facilitated by its

formation of biofilms). The bacterium possess flagella and type 4 pili, which

provide a means of motility and cellular adhesion respectively, but also can

stimulate an inflammatory response.5 Like many other pathogenic

gram-negative bacilli, it possesses a Type 3 secretion system, a needle-like

evolutionary flagellar derivative, which allows it to inject exotoxins directly

through a pore in the cell membrane. It possesses four exotoxins ? exoU, exoS,

exoS, and exoY ? although often not all. ExoS has a deleterious effect on the

actin cytoskeleton and exoU is a potent phospholipase. 5

Chronic infections

in wounds, burns, and ventilator-assisted patients (particularly patients with

cystic fibrosis who are often immunosuppressed) are largely mediated by P.

aeruginosa?s ability to create biofilms.10 Biofilms are highly

structured communities attached to each other and a surface, and act as a

single unit directed by the secretion of diffusible molecules called

autoinducers by dominant bacilli in their midst. Pathogenic strains of Pseudomonas

aeruginosa produce three autoinducers which help organize biofilms in a

variety of situations. 10

One of the most deleterious effects of biofilms is the diffusional resistance

they provide against antimicrobials and some autoinducers upregulate the

production of beta-lactamases by P. aeruginosa, deactivating beta lactam

antibiotics on the surface of the biofilm before they can diffuse into its

depths. Moreover, biofilms protect their community from humoral aspects of

immunity such as antibodies as well as impairing phagocytosis by their sheer

size.10

References:

1. Akiyama H, Kanzaki H, Tada J, Arata J. Staphylococcus aureus infection on cut wounds in the mouse skin: experimental staphylococcal botryomycosis. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;11(3):234-238.

2. Bostrom RE, Huckins JG, Kroe DJ, Lawson NS, Martin JE, Ferrell JF, et al. Atypical fatal pulmonary botryomycosis in two guinea pigs due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1969;155(7):1195-1199.

3. Bridgeford EC, Fox JG, Nambiar PR, Rogers AB. Agammaglobulinemia and Staphylococcus aureus botryomycosis in a cohort of related sentinel Swiss Webster mice. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(5):1881-1884.

4. Casamian-Sorrosal D, Fournier D, Shippam J, Woodward B, Tennant K. Septic pericardial effusion associated with pulmonary and pericardial botryomycosis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2008;49(12):655-659.

5. Gellatly SL, Hancock REW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathog Dis 2013: 67:159-173.

6. Grosset C, Bellier S, Lagrange I, Moreau S, Hedley J, Hawkins M, et al. Cutaneous Botryomycosis in a Campbell?s Russian Dwarf Hamster (Phodopus campbelli). J Exotic Pet Med. 2014;23(4):389-396.

7. Hedley J, Stapleton N, Priestnall S, Smith K. Cutaneous Botryomycosis in Two Pet Rabbits. J Exotic Pet Med. 2019;28(1):143-147.

8 Hussein MR. Mucocutaneous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(11):979-988.

9. Loader H, Lawrence KE, Brangenburg N, Munday JS. Cutaneous botryomycosis in a crossbred domestic pig. N Z Vet J. 2018;66(4):216-218.

10. Mulcahy LR, Isabella VM, Lewis K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in disease. Microb Ecol 2017

11. Padilla-Desgarennes C, Vazquez-Gonzalez D, Bonifaz A. Botryomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(4):397-402.

12. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

13. Read RW, Zhang J, Albini T, Evans M, Rao NA. Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon in the conjunctiva: immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(2):262-266.

14. Shapiro RL, Duquette JG, Nunes I, Roses DF, Harris MN, Wilson EL, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator-deficient mice are predisposed to staphylococcal botryomycosis, pleuritis, and effacement of lymphoid follicles. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(1):359-369.

15. Share B, Utroska B. Intra-abdominal botryomycosis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220(7):1025-1027, 1006-1027.

16. Shults FS, Estes PC, Franklin JA, Richter CB. Staphylococcal botryomycosis in a specific-pathogen-free mouse colony. Lab Anim Sci. 1973;23(1):36-42.