CASE 4: 18-081 (4132734-00)

Signalment:

22-month-old Holstein steer, Bos taurus, bovine.

History:

In June 2018, a Holstein steer in a group of 37 steers in a ?300-hectare farm in Colonia, Uruguay, developed progressive neurological sings including unusual behavior, aimless walking, circling, ataxia, repetitive and uncoordinated tongue movements, and recumbency. The herd grazed on an annual oat pasture and was supplemented with corn silage. A presumptive clinical diagnosis of cerebral listeriosis by the veterinary practitioner prompted treatment with penicillin and streptomycin, however the animal died spontaneously after a clinical course lasting 3 days.

Gross Pathology:

No gross findings.

Laboratory results:

Aerobic and anaerobic bacterial cultures, selective culture for Listeria monocytogenes, PCR for bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 and 5 (BoHV-1 and -5, Varicellovirus), immunohistochemistry for rabies virus (Lyssavirus), West Nile virus (WNV, Flavivirus), and Chlamydia spp. were all negative/unremarkable.

Microscopic description:

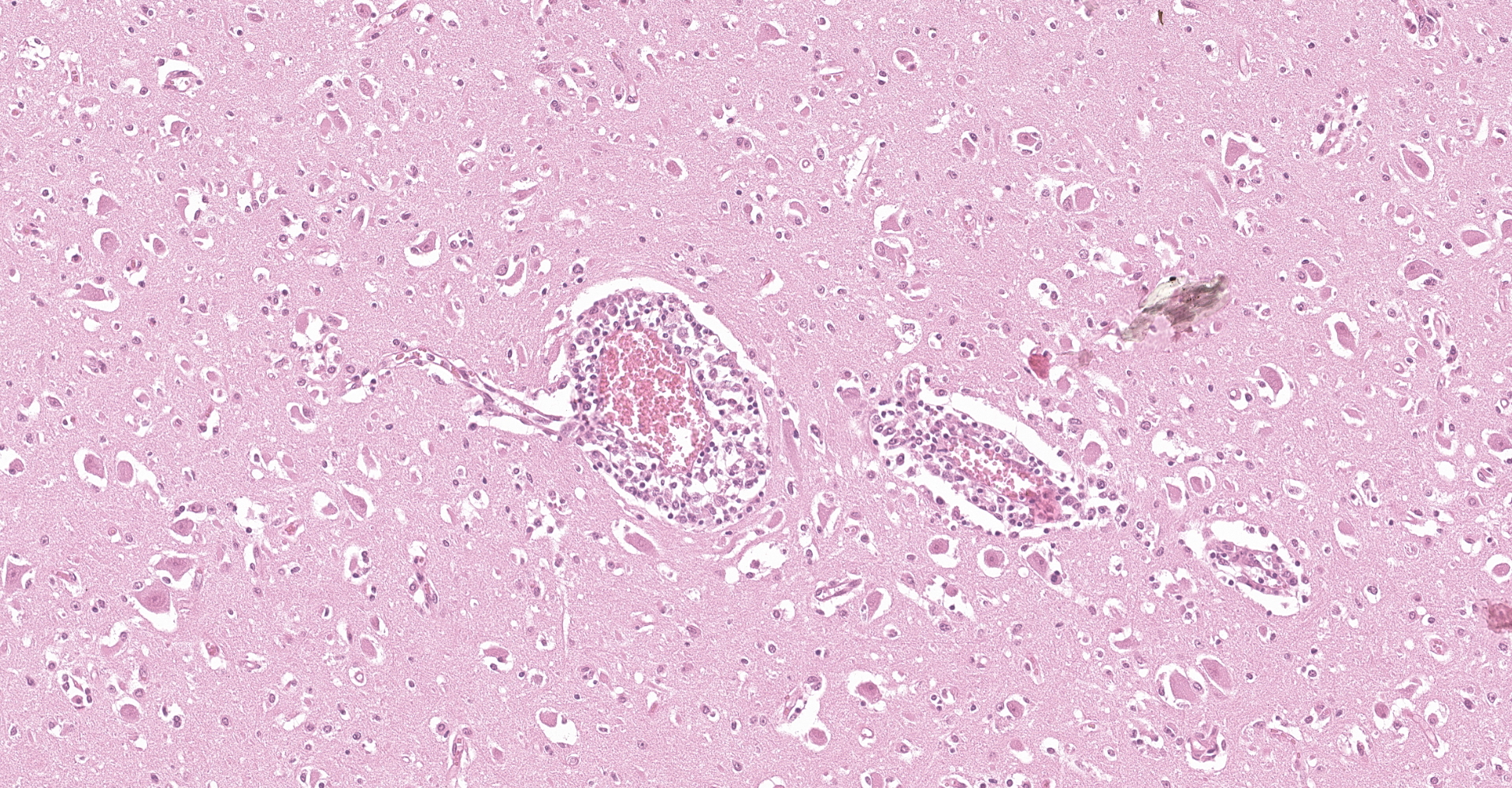

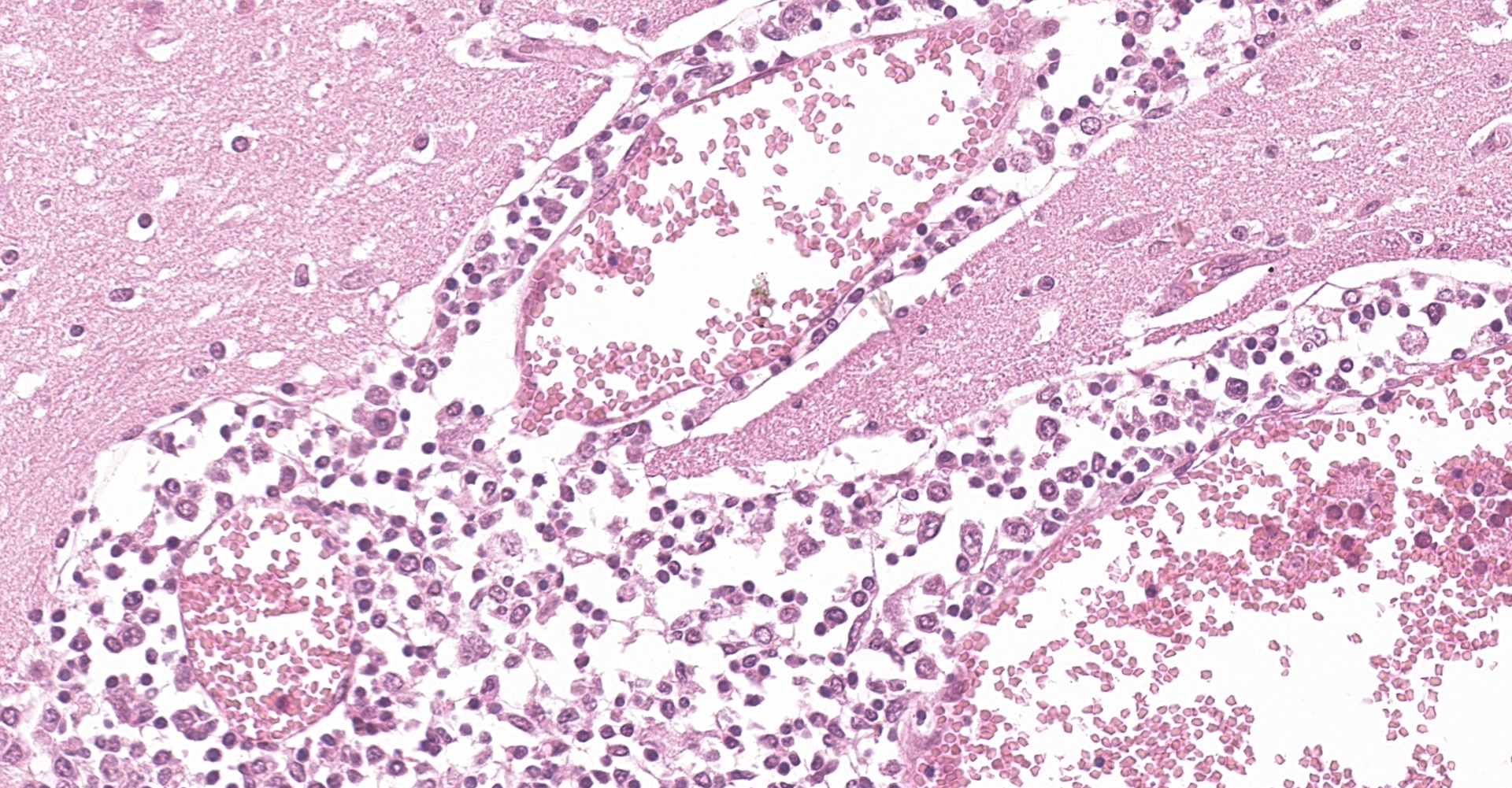

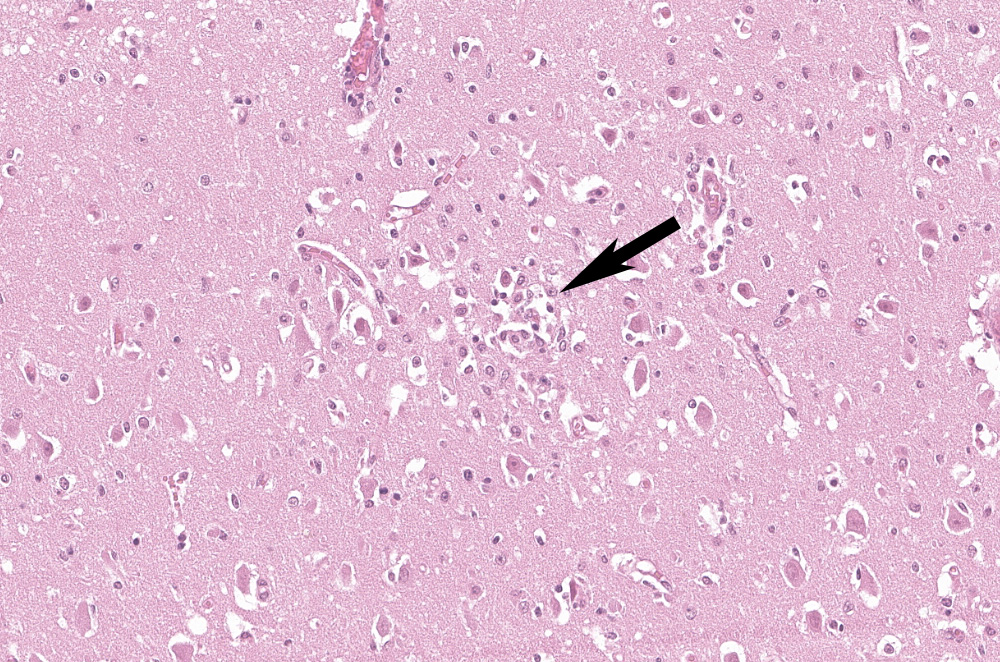

Examined is a section of brain (some slides contain telencephalon and other brainstem). Multifocally and predominantly in the gray matter, the perivascular spaces are expanded by numerous lymphocytes, histiocytes and fewer plasma cells, forming layers up to 20 cells thick (variable in different sections). The inflammatory infiltrate extends into the neuropil in the gray matter, and occasionally limiting areas of the white matter. There are multifocal aggregates of glial cells (microglia, astrocytes) sometimes associated with areas of neuropil rarefaction. Scattered neurons show perikaryal hypereosinophilia, shrinkage, angular borders, and nuclear fading, pyknosis or karyorrhexis (necrosis). Necrotic neurons are sometimes surrounded by inflammatory and glial cells (satellitosis) or invaded by them (neuronophagia, not present in all sections). Some axons are swollen and hypereosinophilic (spheroids/torpedoes). The leptomeninges are multifocally infiltrated by small numbers of lymphocytes, histiocytes and fewer plasma cells (not present in all sections).

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Brain (telencephalon or brainstem): meningoencephalitis, lymphocytic, histiocytic and plasmacytic with neuronal necrosis, multifocal, subacute, moderate to severe, bovine.

Contributor's comment:

The diagnosis of bovine astrovirus-associated encephalitis in this case was based on the microscopic lesions, typical of viral encephalitis, coupled with intralesional identification of BoAstV RNA within neurons by in situ hybridization, and molecular identification of BoAstV by RT-PCR followed by whole genome sequencing. Other viral and bacterial causes of encephalitis in cattle were ruled out by specific testing.

The Astroviridae family contains non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses within two genera, Mamastrovirus and Avastrovirus, which infect mammals and birds, respectively. Currently, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses11 recognizes 19 species, namely Mamastrovirus-1 through -19, within the Mamastrovirus genus; however, there are numerous strains awaiting classification, some of which are tentatively considered new species.8

Since 2010, several astroviruses have increasingly been recognized as neuroinvasive in various mammalian species, including humans,16,18 mink,1 cattle,14 sheep,17 pigs,2 and muskox.3 After initial recognition of bovine astrovirus-associated encephalitis in United States cattle,14 a retrospective study in cases of sporadic bovine encephalitis of undetermined etiology from Switzerland revealed that this neuroinvasive astrovirus had gone undetected for decades.23 Although the epidemiology and transmission routes of these astroviruses are unknown, cross-species transmission has been suggested based on the high level of identity (>98%), shared between bovine and ovine neuroinvasive astroviruses at the nucleotide and amino acid levels.4

Bovine astroviruses (BoAstVs), named BoAstV-NeuroS114 and BoAstV-CH13,6 were initially found in the brain of cattle with non-suppurative encephalitis in the United States and Switzerland, respectively. Despite the different nomenclature, both viruses represent the same genotype species5,21 that is still awaiting official classification by the ICTV. In 2015, a previously unknown BoAstV strain, named BoAstV-CH15, was identified in the brain of cows with encephalitis in Switzerland. Full genome phylogenetic comparison revealed a closer relationship of BoAstV-CH15 with an ovine astrovirus (OvAstV) than with BoAstV-CH13.24 Coinfection with BoAstV-CH13 and BoAstV-CH15 was also documented in one case.24 The same year in Germany, Schlottau et al. (2016)20 reported a novel astrovirus, namely BoAstV-BH89/14, in a cow with encephalitis, that was most closely related to OvAstV and BoAstV-CH15. Subsequently, BoAstV-CH13/NeuroS1 was identified in 2017 in cases of bovine encephalitis in eastern and western Canada.22,25 In 2018, a novel neuroinvasive BoAstV closely related with North American and European BoAstV-NeuroS1/BoAstV-CH13, was identified in a steer with non-suppurative encephalomyelitis in Japan, and the occurrence of intra-genotypic recombination between the North American and European strains was suggested.10

While in the northern hemisphere cases of BoAstV-associated encephalitis have been reported in North America, Europe, and Asia, in the southern hemisphere the disease so far has only been documented in Uruguay9 and is probably underdiagnosed. A Bayesian phylogeographic analysis including North American, European, Asian and the Uruguayan strain suggested that the common viral ancestor circulated in Europe between 1794-1940, and was introduced in Uruguay between 1849-1976, to later spread to North America and Japan.9

The clinical signs and epidemiological findings in the case described herein, albeit non-specific, were similar to those described in other cases of bovine astrovirus-associated encephalitis, which is usually described as sporadic,23 with a variety of neurological deficits,7 with a duration of clinical signs that typically ranges from 1 day to 3 weeks.7,10,20,25

Macroscopic examination of the brain and the C1 segment of the spinal cord did not reveal significant gross anatomic lesions. Histologically, there was moderate to severe, lymphocytic, histiocytic and plasmacytic meningoencephalomyelitis affecting the telencephalon (including the cerebral hemisphere and hippocampus), brainstem, and the only examined segment of spinal cord. Lesions were predominantly distributed in the gray matter and limiting areas of white matter. In affected areas there was perivascular cuffing and lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation and neuronal necrosis/neuronophagia with gliosis in the adjacent neuropil. There was satellitosis of affected, necrotic neurons. The lesions were much less frequent and severe in the cerebellar parenchyma, although there was multifocal moderate cerebellar leptomeningitis. No intralesional bacteria were found with H&E and Gram stains, and no viral inclusions were identified. In situ hybridization was performed using a probe generated from BoAstV-NeuroS1, and there was probe hybridization abundant within, and limited to the cytoplasm of neurons in the cerebral hemisphere and hippocampus.

Astrovirus was detected in brain by RT-PCR. Nearly complete genome sequence analysis revealed a Mamastrovirus strain within the CH13/NeuroS1 clade, we named BoAstV-Neuro-Uy (GenBank under accession number MK386569). Phylogenetic analysis suggests that BoAstV-Neuro-Uy and other members of this clade should be classified within one same species; Mamastrovirus-13, as proposed by others,8,10 although definite species assignation by the ICTV is pending.

Additional details and figures of the case presented here were published elsewhere.9 A detailed review on neurotropic astroviruses in humans and animals is also available in the literature.19

Contributing Institution:

Plataforma de Investigación en Salud Animal, Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria (INIA), La Estanzuela, Uruguay, www.inia.uy

JPC diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, lymphohistiocytic, diffuse, moderate, with gliosis and rare glial nodules.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides an excellent and well researched summary of bovine astrovirus, with important knowledge gaps identified, but still remaining. Since their first description in 1975, astroviruses have become an important cause of gastroenteritis in human children and some domestic species, but also encephalitis in cattle, mink, sheep, pigs, and humans, and hepatitis and nephritis in avians. Astroviruses are so named because when visualized on TEM, the surface of some virus particles has a distinct star-like shape.15

It was recently hypothesized that the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract may serve as a reservoir for encephalitis causing astroviruses in cattle in Switzerland. Nasal and fecal swabbing of study veal calves resulted in two positive animals using RT-qPCR protocols, infected with BoAstV-CH13/NeuroS1. Additional research is required to determine whether the hypothesis is correct, but fecal samples may be a relatively simple method to determine infection status of specific animals.12

A recent case of neurotropic astrovirus was reported in an alpaca in Switzerland. The patient presented for anorexia, trembling, two day duration of colic, and general ill thrift. After several days with progressive neurologic signs, the animal was euthanized. Histology identified non-suppurative polioencephalomyelitis, with prominent lymphohistiocytic perivascular cuffs, multifocal neuronal degeneration and necrosis, and multifocal glial nodules. RT-qPCR, Next Generation Sequencing, IHC, and in situ hybridization determined that the causative agent was a virus almost identical to BoAstV-CH13/NeuroS1. In endemic areas, this virus should remain on the differential diagnosis list in cattle and other domestic species.13

During the conference, the moderator emphasized the different between astrocytosis and astrogliosis. Astrocytosis indicates a raw increase in number of astrocytes, while astrogliosis indicates an increased in reactive astrocytes. The two terms are easily confused, but are often consistent with different pathologic processes.

References:

- Blomström AL, Widén F, Hammer AS, Belák S, Berg M. Detection of a novel astrovirus in brain tissue of mink suffering from shaking mink syndrome by use of viral metagenomics. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4392?4396.

- Boros Á, Albert M, Pankovics P, Bíró H, Pesavento PA, Phan TG, et al. Outbreaks of neuroinvasive astrovirus associated with encephalomyelitis, weakness, and paralysis among weaned pigs, Hungary. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1982?1993.

- Boujon CL, Koch MC, Kauer RV, Keller-Gautschi E, Hierweger MM, Hoby S, Seuberlich T. Novel encephalomyelitis-associated astrovirus in a muskox (Ovibos moschatus): A surprise from the archives. Acta Vet Scand. 2019;61:31.

- Boujon CL, Koch MC, Wüthrich D, Werder S, Jakupovic D, Bruggmann R, et al. Indication of cross-species transmission of astrovirus associated with encephalitis in sheep and cattle. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1604?1608.

- Bouzalas IG, Wüthrich D, Selimovic-Hamza S, Drögemüller C, Bruggmann R, Seuberlich T. Full-genome based molecular characterization of encephalitis-associated bovine astroviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;44:162?168.

- Bouzalas IG, Wüthrich D, Walland J, Drögemüller C, Zurbriggen A, Vandevelde M, et al. Neurotropic astrovirus in cattle with nonsuppurative encephalitis in Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3318?3324.

- Deiss R, Selimovic-Hamza S, Seuberlich T, Meylan M. Neurologic clinical signs in cattle with astrovirus-associated encephalitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31:1209?1214.

- Donato C, Vijaykrishna D. The broad host range and genetic diversity of mammalian and avian astroviruses. Viruses. 2017;9:E102.

- Giannitti F, Caffarena RD, Pesavento P, Uzal FA, Maya L, Fraga M, Colina R, Castells M. The first case of bovine astrovirus-associated encephalitis in the Southern hemisphere (Uruguay), uncovers evidence of viral introduction to the Americas from Europe. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1240.

- Hirashima Y, Okada D, Shibata S, Yoshida S, Fujisono S, Omatsu T, et al. Whole genome analysis of a novel neurotropic bovine astrovirus detected in a Japanese black steer with non-suppurative encephalomyelitis in Japan. Arch Virol. 2018;163 2805?2810.

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [ICTV] (2018). Master Species List (MSL32), Version 1. Available at: https://talk.ictvonline.org/files/master-species-lists/m/msl/7185 (accessed March, 2019).

- Kauer RV, Koch MC, Schonecker L, et al. Fecal Shedding of Bovine Astrovirus CH13/NeuroS1 in Veal Calves. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2020;58(5):e01964-19.

- Kuchler L, Rufli I, Koch MC. Astrovirus-Associated Polioencephalomyelitis in an Alpaca. Viruses. 2021;13(1):50.

- Li L, Diab S, McGraw S, Barr B, Traslavina R, Higgins R, et al. Divergent astrovirus associated with neurologic disease in cattle. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1385?1392.

- MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. Caliciviridae and Astroviridae. In: Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Ed. San Diego, CA:Elsevier. 2017:506-510.

- Naccache SN, Peggs KS, Mattes FM, Phadke R, Garson JA, Grant P, et al. Diagnosis of neuroinvasive astrovirus infection in an immunocompromised adult with encephalitis by unbiased next-generation sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60 919?923.

- Pfaff F, Schlottau K, Scholes S, Courtenay A, Hoffmann B, Höper D, et al. A novel astrovirus associated with encephalitis and ganglioneuritis in domestic sheep. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64:677?682.

- Quan PL, Wagner TA, Briese T, Torgerson TR, Hornig M, Tashmukhamedova A, et al. Astrovirus encephalitis in boy with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:918?925.

- Reuter G, Pankovics P, Boros A. Nonsuppurative (aseptic) meningoencephalomyelitis associated with neurovirulent astrovirus infections in humans and animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31:e00040-18.

- Schlottau K, Schulze C, Bilk S, Hanke D, Höper D, Beer M, et al. Detection of a novel bovine astrovirus in a cow with encephalitis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63:253?259.

- Selimovic-Hamza S, Boujon CL, Hilbe M, Oevermann A, Seuberlich T. Frequency and pathological phenotype of bovine astrovirus CH13/NeuroS1 infection in neurologically-disease cattle: towards assessment of causality. Viruses. 2017a;9:E12.

- Selimovic-Hamza S, Sanchez S, Philibert H, Clark EG, Seuberlich T. Bovine astrovirus infection in feedlot cattle with neurological disease in western Canada. Can Vet J. 2017b;58 601?603.

- Selimovic-Hamza S, Bouzalas IG, Vandevelde M, Oevermann A, Seuberlich T. Detection of astrovirus in historical cases of European sporadic bovine encephalitis, Switzerland 1958-1976. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:91.

- Seuberlich T, Wüthrich D, Selimovic-Hamza S, Drögemüller C, Oevermann A, Bruggmann R, et al. Identification of a second encephalitis-associated astrovirus in cattle. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e5.

- Spinato MT, Vince A, Cai H, Ojkic D. Identification of bovine astrovirus in cases of bovine non-suppurative encephalitis in eastern Canada. Can Vet J. 2017;58:607?609.