WSC 2022-2023

Conference 24

Case I:

Signalment:

13-day old male Holstein calf.

History:

This male Holstein calf was unable to stand since birth. There were increased lung sounds and bilateral nasal discharge. There was asymmetry in the right tuber- coxae. Radiographic changes suggested congenital unilateral hip dysplasia.

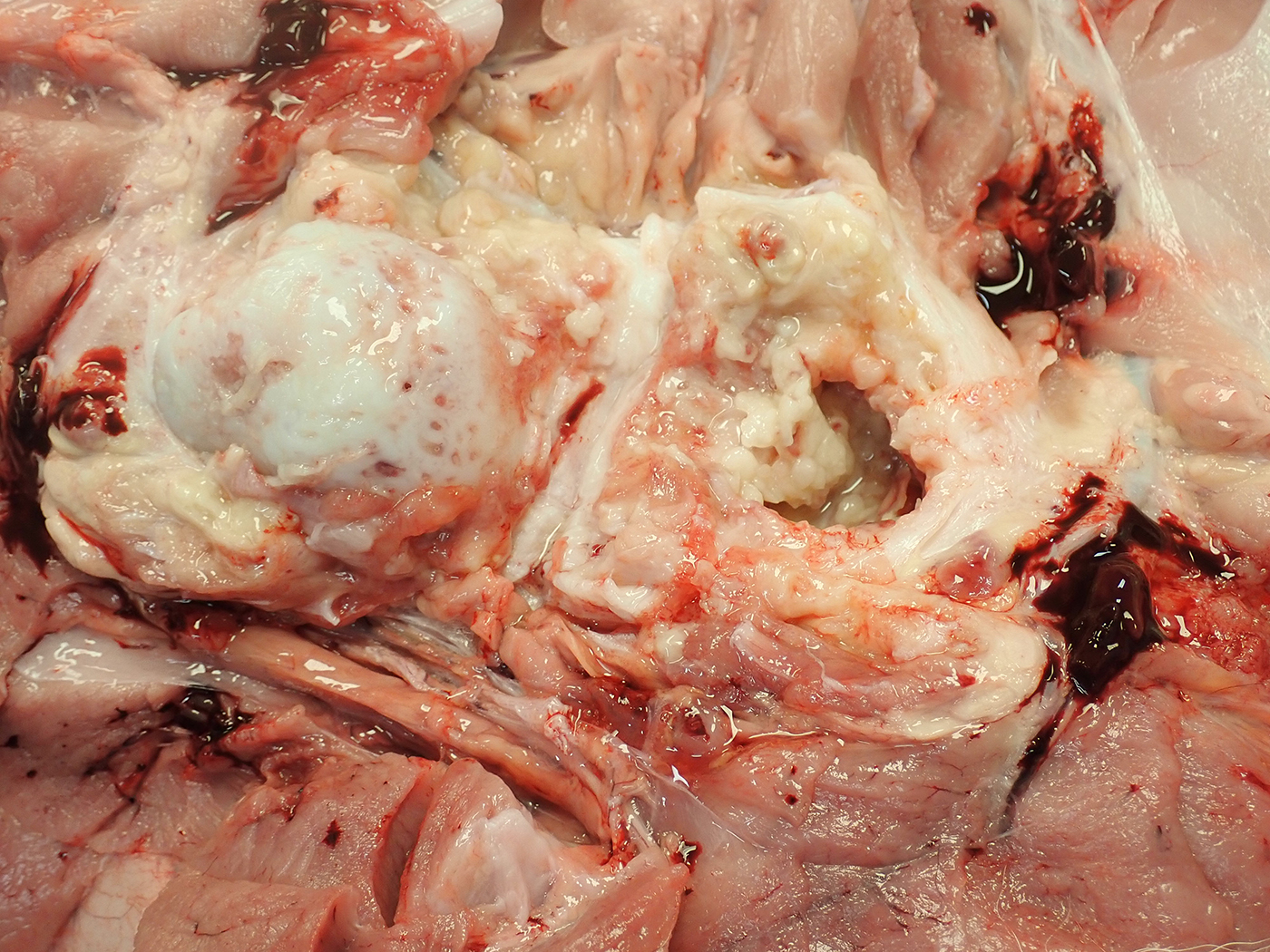

Gross Pathology:

The calf was in good body condition with symmetrical muscle mass but was smaller than normal. The umbilical stump is dry.

The joint capsule of the right coxofemoral joint is thickened up to 2 cm by tough white fibrous tissue and gelatinous or clear to yellow fluid. Within the joint capsule are thick mats of yellow-tan friable material resembling fibrin. The synovial fluid is yellow and less viscous than normal. The cartilage of the femoral head is dull and irregular with a punctate to moth-eaten appearance. There is gelatinous thin strands of fibrin with focal hemorrhage within the left stifle and right tarsal joint. The rest of the body was normal.

Laboratory Results:

No aerobic or anaerobic bacteria were isolated from the hip joint. The joint capsule was positive for Ureaplasma sp by PCR

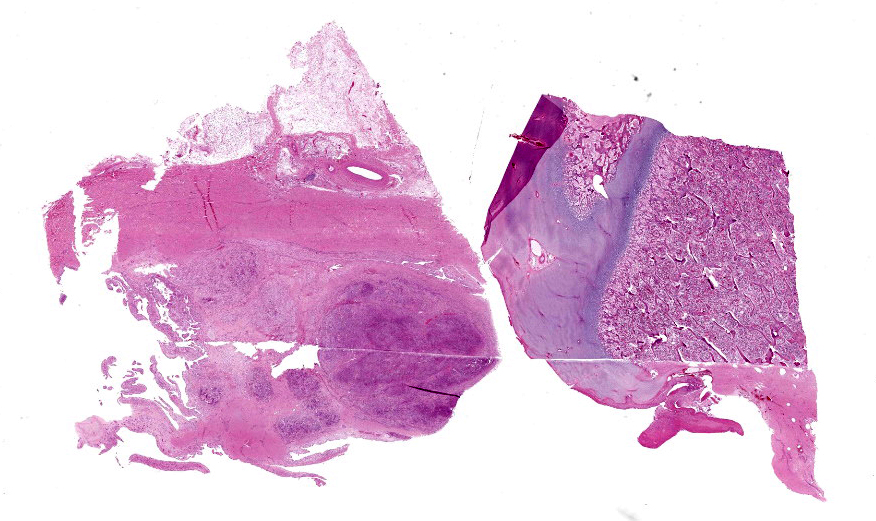

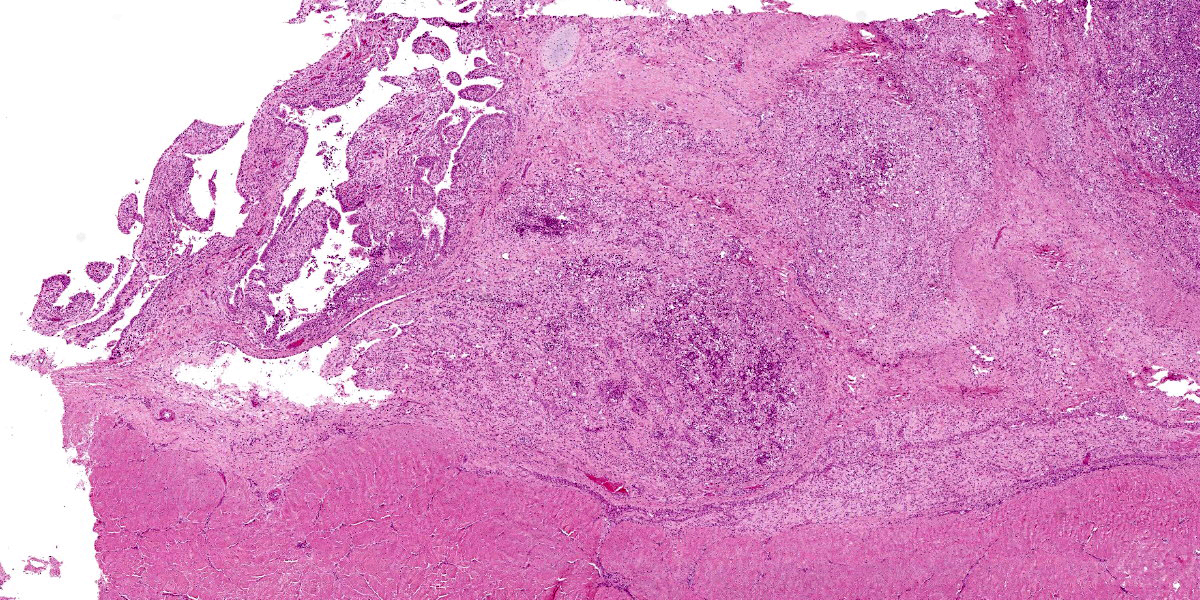

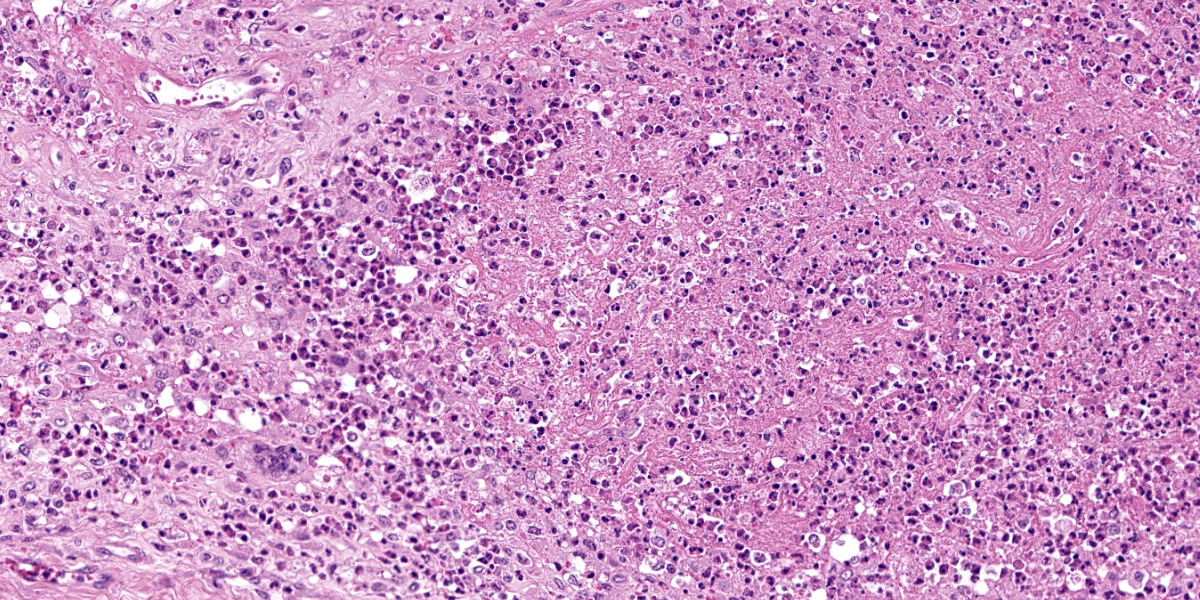

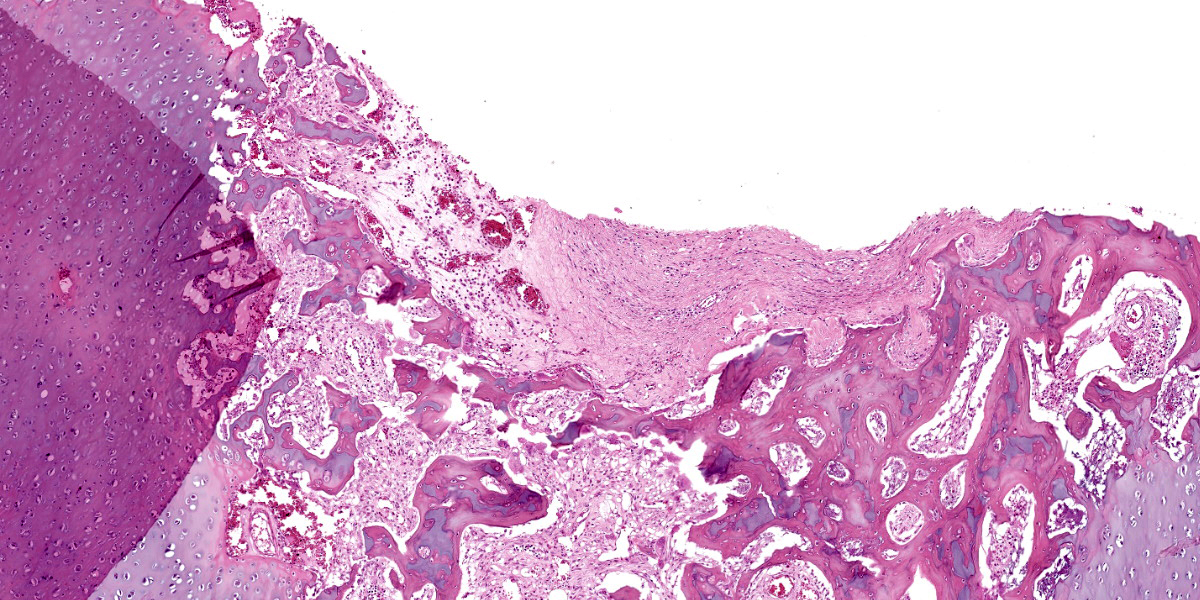

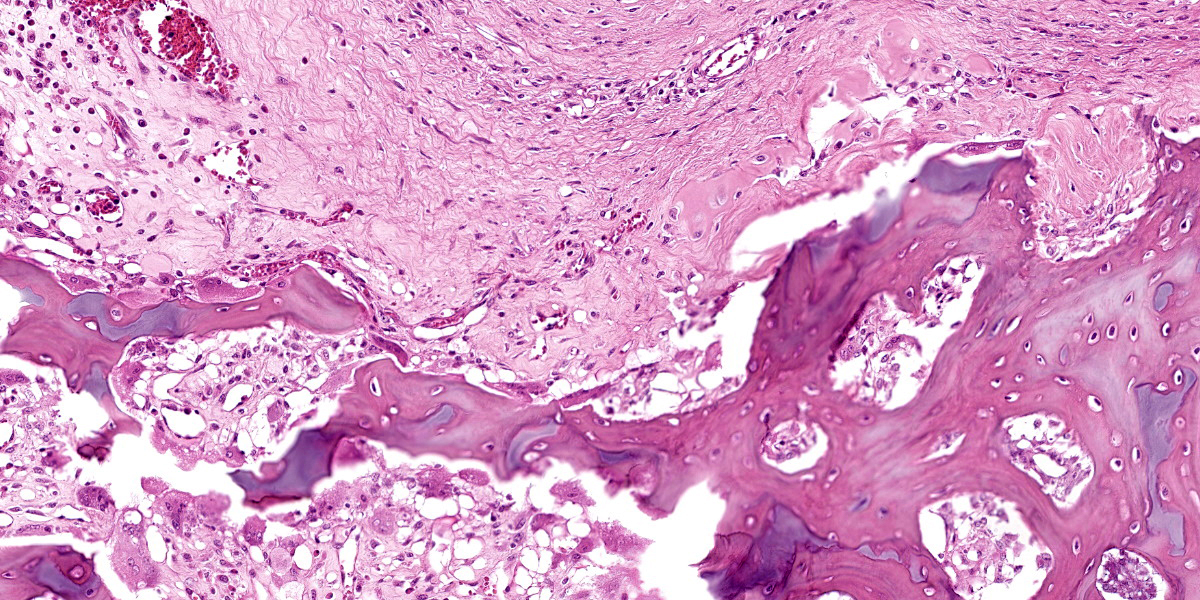

Microscopic Description:

The tissue on this slide includes joint capsule with synovial membrane, femoral head with articular epiphyseal cartilage complex, epiphysis, physeal cartilage and metaphysis. Within the wall of the joint capsule are aggregates of neutrophils and macrophages with high-protein fluid including fibrin. There is fibrous tissue surrounding these areas. The synovial membrane has villus formation and synoviocytes are hypertrophied and up to 3 cells thick.

There is fibrin with neutrophils beneath the synovial membrane at the transition zone, the junction between joint capsule and periosteum. The articular epiphyseal cartilage complex is mostly normal however within the epiphysis is a region of fibrosis and connective tissue replacement of hematopoietic marrow of the intertrabecular spaces. Some of this fibrous tissue has mature collagen.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Osteomyelitis of femoral head, neutrophilic and histiocytic fibrosing joint capsulitis/periarthritis and synovial hyperplasia.

Contributor’s Comment:

The history, diagnostic imaging findings, gross pathology findings and histopathology indicates this is a congenital infectious arthritis and osteomyelitis. The identification of Ureaplasma confirms this as fetal infection and arthritis with Ureaplasma diversum. This is an uncommon manifestation of Ureaplasma infection, which is better known for inducing amnionitis and fetal pneumonia with large lymphoid follicles around bronchi. The location of the reaction in the coxofemoral joint is typical of this entity.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiology, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph,

Guelph, Ontario, Canada

https://ovc.uoguelph.ca/pathobiology/

JPC Diagnosis:

Coxofemoral joint: Arthritis, pyogranulomatous and proliferative, diffuse, severe, with osteomyelitis and articular cartilage necrosis and erosion.

JPC Comment:

In large animals, neonatal polyarthritis is commonly the result of systemic infection secondary to omphalophlebitis and/or failure of passive transfer with subsequent immunodeficiency. In calves, the most common organisms associated with neonatal polyarthritis are coliforms and streptococcus. Both agents result in systemic lesions, including fibrinosuppurative meningitis and polyarthritis. Streptococcus septicemia also characteristically causes embolic iridocyclitis with hypopyon and corneal clouding.3

Another important differential for polyarthritis in calves is Mycoplasma bovis¸ which belongs to the same order as Ureaplasma.3 M. bovis causes a variety of diseases in cattle including pneumonia, mastitis, otitis media in calves, and polyarthritis.3 Calves are infected by consuming the bacterium in the milk of infected cows and often develop concurrent pneumonia. Histologically, affected joints have fibrinosuppurative and erosive arthritis with synovial hyperplasia.3

Ureaplasma diversum differs from these neonatal infections as infection in calves begins in-utero. U. diversum is a common commensal organism found in the nasal passage and male and female reproductive tracts of cattle.6 The bacteria is transmitted by coitus and as a major cause of reproductive loss in cattle.5 It causes urogenital infections such as vaginitis and endometritis in cows and seminal vesiculitis in bulls.6 Pregnant cows infected with virulent strains may have third trimester abortions or give birth to weak or stillborn calves.5 The bacterium causes necrotizing placentitis and mild arteritis which affect the amnion more severely than the chorioallantois.5 Aborted calves are well preserved and fetal membranes may be retained. Calves may have erosive conjunctivitis and nonsuppurative alveolilis.5 Interstitial pneumonia in a calf due to U. diversum was recently seen in WSC, year 2021-2022, Conference 24, Case 2; readers are encouraged to review that case for a full histologic picture of the infection in calves.

This case illustrates another sequela to U. diversum infection in utero: severe erosive polyarthritis3,4. The infection may affect one or multiple joints and tends to target the coxofemoral joint, shoulders, elbows, stifle, and carpal and tarsal joints.3,4 In affected joints, articular surfaces are deformed, with irregularly thinned cartilage and extensive granulation tissue that extends into the subchondral bone.3,4

One last differential to consider for severe polyarthritis in calves is Chlamydia pecorum. Infection may occur due to ingestion of the bacteria or in-utero infection.3 Virulent strains of this obligate intracellular bacteria spread from the intestine via portal circulation to the liver and then systemically were it ultimately finds the joints.3 Affected animals are febrile, depressed, and reluctant to move.3 In addition to severe polyserositis and meningoencephalitis, there is severe serofibrinous arthritis with edema and petechiation in the adjacent soft tissue.1,3

Conference participants discussed the quality of the primary and secondary spongiosa in this section. The thin, delicate spicules that with retained cartilage cores led some conference participants to consider osteogenesis imperfecta as a secondary process. According to the history provided by the contributor, this animal was never able stand, so participants also considered disuse osteopenia as a potential cause for these findings.

References:

- Cantile C, Youssef S. The nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed., Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd.; 2016:391-392.

- Carli SD, Dias ME, da Silva M, Breyer GM, Siqueira FM. Survey of beef bulls in Brazil to assess their role as source of infectious agents related to cow infertility. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022;34(1): 54-60.

- Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson KG. Bones and Joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 154.

- Himsworth CG, Hill JE, Huang Y, Waters EH, Wobeser GA. Destructive polyarthropathy in aborted bovine fetuses: a possible association with Ureaplasma diversum infection? Vet Pathol. 2009; 46(2): 269-72.

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female Genital System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:399-402, 411-416.

- Strait EL, Madsen ML. Mollicutes. In: McVey DS, Kennedy M, Chengappa MM, eds. Veterinary Microbiology. 3rd Ames, IO: Wiley Blackwell. 283-292.