CASE I:

Signalment: 1.5-year-old male New Zealand white rabbit (Oryctolaguscuniculus)

History: This 1.5-year-old rabbit (R-857) was found dead in his cage on 4/25/2023. He was on a behavioral study with a high cholesterol diet. An autopsy was performed, and formalin fixed liver, heart, and kidney were submitted to the Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

Gross Pathology: Veterinarian who performed the autopsy noted the liver was diffusely dark green and stomach contained food but was not distended.

Laboratory Results: Not applicable.

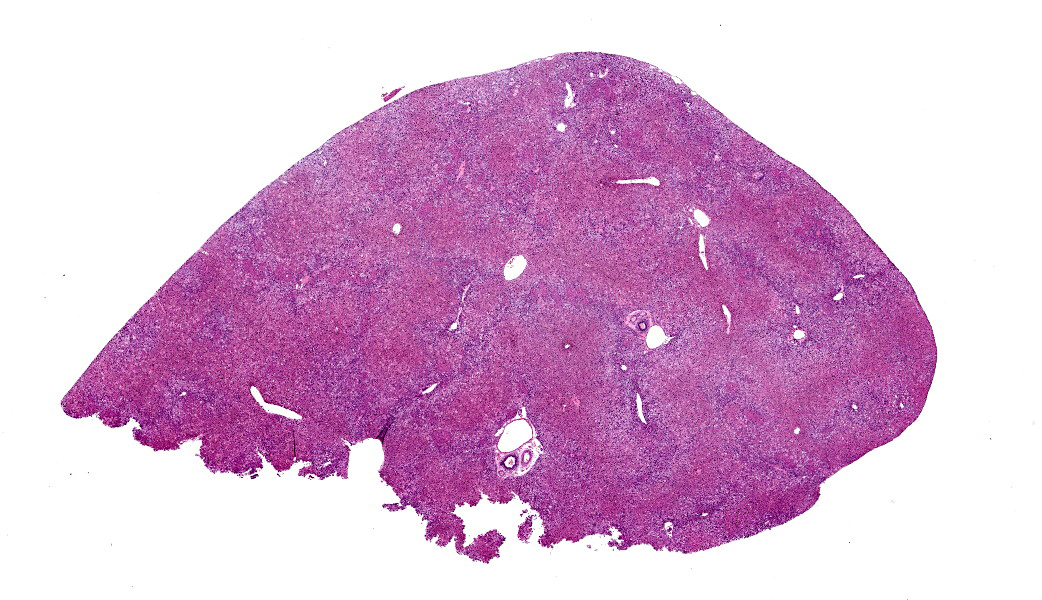

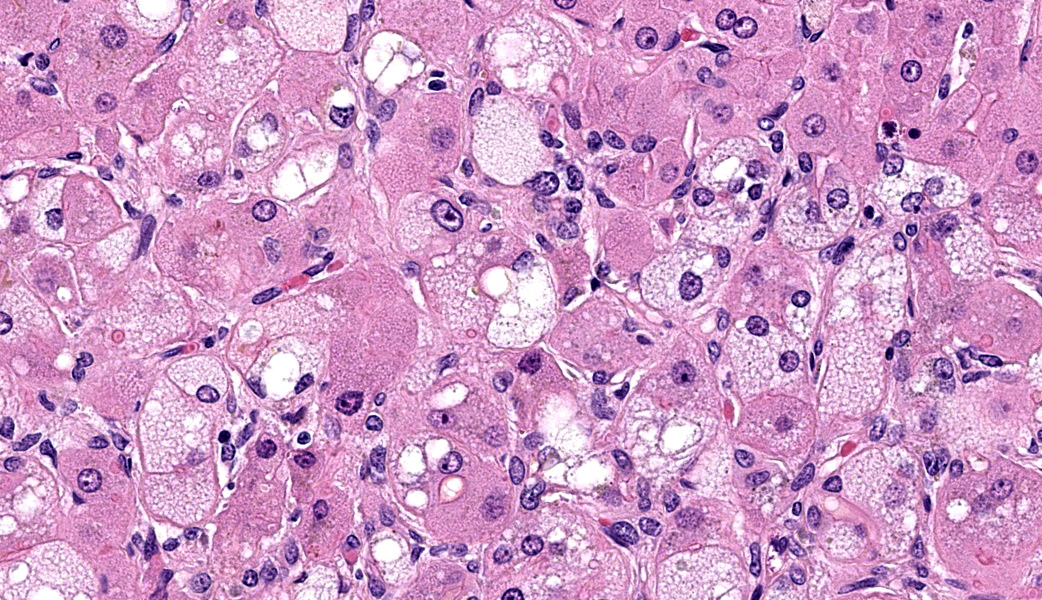

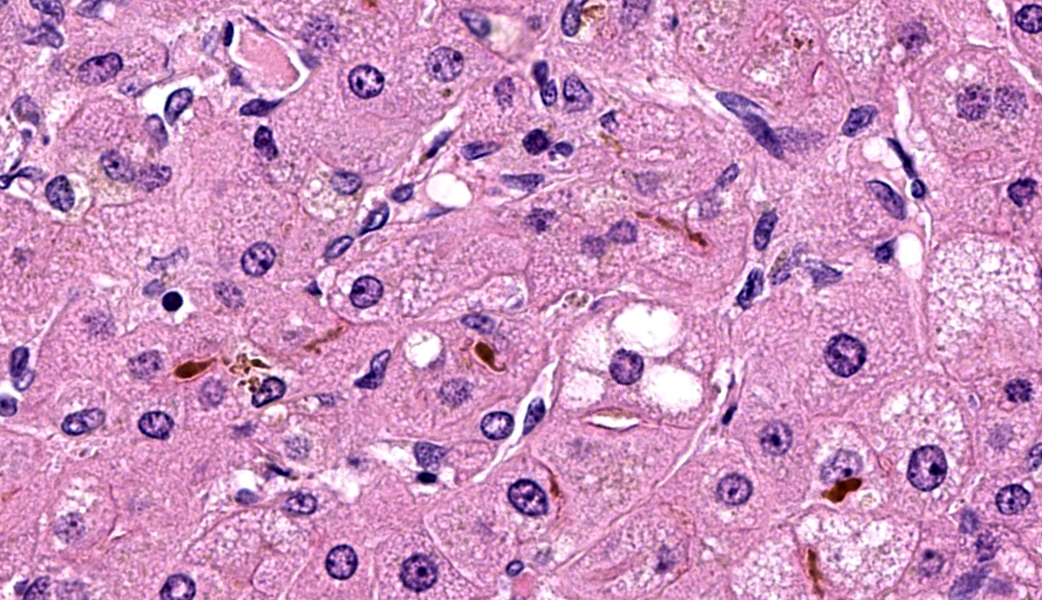

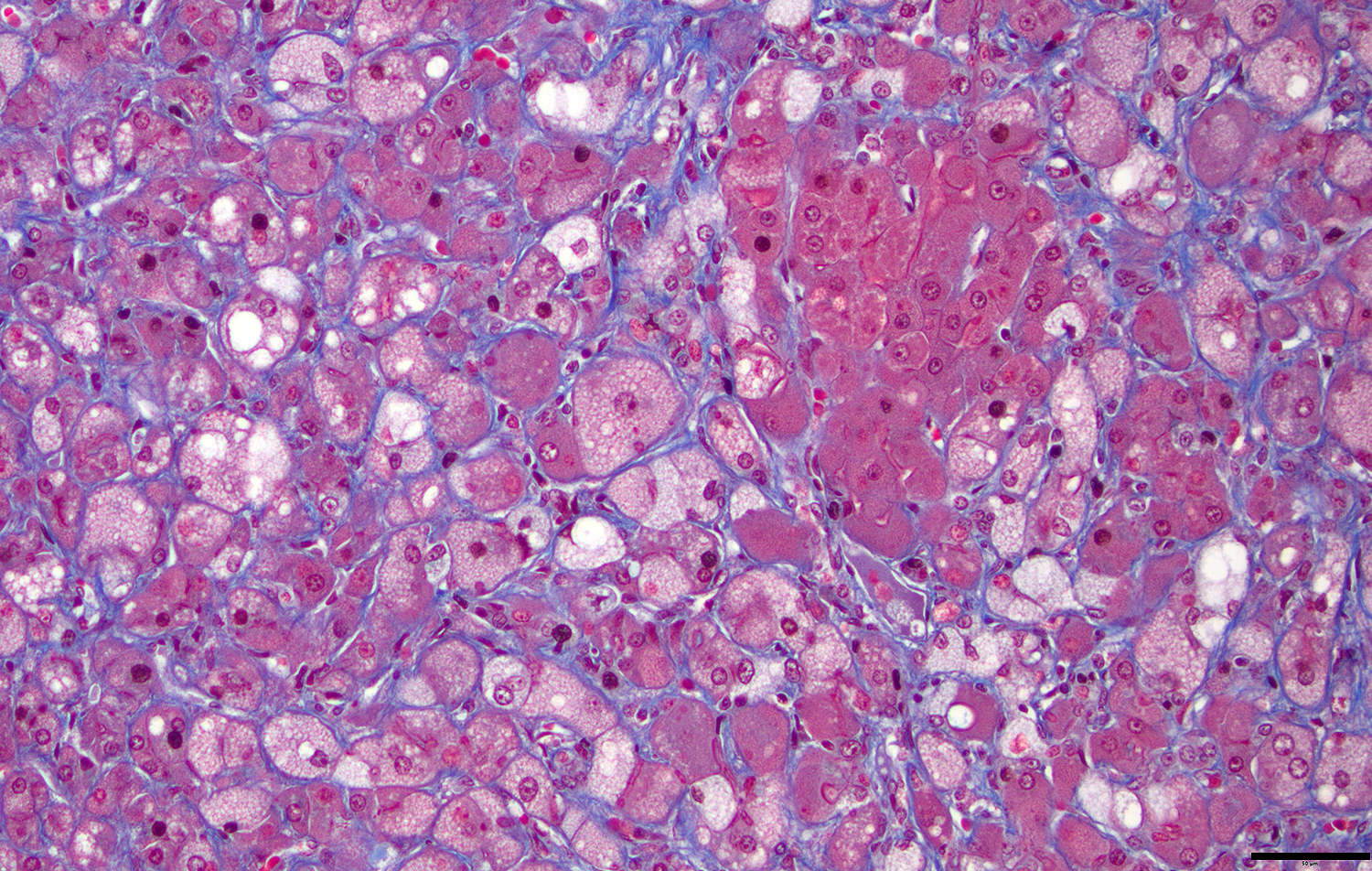

Microscopic Description: Approximately 60% of the hepatocytes in mostly periportal and centrilobular regions are markedly expanded by high numbers of microvesicular vacuolations (steatosis/lipid) and more rarely macrovesicular vacuolations or a mixture of the two. Sinusoids contain increased myofibroblasts (activated hepatic stellate cells) causing multifocal collapse of hepatocellular cord architecture. The myofibroblasts extend near portal areas, but distinct biliary hyperplasia is not appreciated. Occasionally hepatocytes are dissociated and composed of hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and lack a nucleus (necrosis). There are occasional binucleated hepatocytes. Canaliculi are multifocally, mildly expanded by tan to brown material (bile). Very rare lymphocytes are within sinusoids and in portal areas.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis with sinusoidal fibrosis and cholestasis

Contributor’s Comment: Hepatic steatosis or lipidosis is a common sequela to high cholesterol diets in rabbits, including New Zealand white rabbits.6 Rabbits are highly susceptible to hypercholesterolemia and subsequent atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis.1,6 Hypercholesterolemia and hyperlipidemia also occur in rabbits affected by inflammatory processes and disease, without a high cholesterol diet.9 In rabbits, hypercholesterolemia is accompanied by increased circulating very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and low-density lipoproteins (LDL).1 The VLDL (specifically β- VLDL) lead to the lesions of atherosclerosis, and both VLDL and LDL are transported to and from hepatocytes via LDL receptors.1,11 In rabbits and humans, hepatic steatosis can occur if cholesterol and triglycerides, in the form of VLDL and LDL, overload hepatocytes. In humans and animals with metabolic syndrome, ruminants, and cats, adipose tissue is broken down, releasing triglycerides or free fatty acids which go to the liver and similarly overload the hepatocytes.3,11 Synthesis of VLDL in hepatocytes occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and there is some mitochondrial oxidation normally. When overloaded, there can be ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction associated with lipotoxic metabolites of fatty acids, thus leading to more steatosis.5 Therefore, hepatic steatosis pathogenesis includes both the triglycerides themselves, as well as lipotoxic metabolites.

Steatosis occurs in a macrovesicular or microvesicular form. Macrovesicular steatosis is more often associated with hepatic lipidosis as seen in cats, ruminants, and animals with metabolic syndrome. Both macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis are due to triglyceride accumulation. Microvesicular steatosis is also associated with mitochondrial dysfunction4 and is most common in toxic hepatopathies, like Reye’s syndrome in humans3,4. The mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity are likely why microvesicular steatosis has a poorer prognosis.

Hepatic steatosis in humans is referred to as non-alcoholic or metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (NAFLD and MAFLD) and can lead to steatohepatitis (NASH or MASH) 7. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is associated with steatosis, inflammation, hepatocellular degeneration, and fibrosis, almost all clearly displayed in this rabbit and in a rabbit model2. This rabbit and humans with MASH often also have concurrent hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis2.

The liver histopathology in this case also provided opportunity to review the classic lesions of liver repair. One group of progenitor cells in the liver (also termed oval cells in rodents) is located within the canals of Hering. When the liver is damaged, these cells are activated and lead to histopathologic “biliary duct hyperplasia”, “ductular reaction”, or “oval cell activation” 8. In addition to this population of progenitor cells are hepatic stellate cells. Hepatic stellate cells reside in the space of Disse along the sinusoids and are activated from relatively quiescent cells into myofibroblasts when there is liver damage3,8. This case highlights early fibrosis within the sinusoids or space of Disse due to activation of hepatic stellate cells.

Contributing Institution:

Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

4125 Beaumont Road

Lansing, MI 48910-8104

https://cvm.msu.edu/vdl

JPC Diagnoses: Liver: Hepatocellular micro- and macrovesicular lipidosis, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with marked stellate cell hyperplasia and cholestasis.

JPC Comment: Conference 13 was moderated by the Dr. Louis Huzella, a previous graduate of this program during the AFIP years. As his conference was held the day before the Thanksgiving holiday here in the U.S., he selected cases that he felt were loosely in keeping with that theme. This made for an enjoyable and light-hearted conference to with which to wrap up the 2025 conferences.

The contributor in this case provided a well-thought and informative writeup of hepatic lipidosis and hyperlipidemia, and much of what was discussed in conference is covered in their comment. Conference participants were, for the most part, readily able to achieve the reach the correct morphologic diagnosis in this case, but there was some speculation on the origin of the hyperplastic spindle cell population on the H&E. As mentioned by the contributor, there are two main possibilities: oval cells or stellate cells. Oval cells are bipotential progenitors of both hepatocytes and biliary ductular epithelial cells. Hepatic stellate cells, also called Ito cells, live primarily in the space of Disse, store Vitamin A, and can be activated into myofibroblasts following injury that will produce connective tissue components.3,8 Participants wondered if there was both oval cell and stellate cell hyperplasia in this case due to the presence of mild ductular reaction, cholestasis, and fibrosis, but unanimously agreed that there was at least stellate cell activation due to the fibrosis highlighted by a Masson’s trichrome. This is a difficult distinction to make on H&E alone.

Of laboratory animal species, rabbits are more similar to humans in lipoprotein metabolism, atherosclerosis, and myocardial function than are rats and mice.10 The Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbit is a specific strain of New Zealand White rabbit that was developed in Japan and is used as an animal model of familial hypercholesterolemia. Within the WHHL strain, there are two additional advanced strains used for specific hyperlipidemia-related diseases processes and include the coronary atherosclerosis-prone WHHL rabbit and the myocardial infarction-prone WHHL rabbit.10 Hypercholesterolemia in the WHHL rabbit family is due to reduced LDL uptake by the liver.10 Watanabe rabbits have played an important role in advancing these research areas and enabling a better understanding of these diseases in humans and animals alike. Additionally, studies in Watanabe rabbits have led to the development of a number of statins, which are inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis, to help treat hypercholesterolemia in humans.10

References:

- Fan J, Kitajima S, Watanabe T, et al.. Rabbit models for the study of human atherosclerosis: from pathophysiological mechanisms to translational medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;146:104-119.

- Hayashi M, Kuwabara Y, Ito K, et al. Development of the Rabbit NASH Model Resembling Human NASH and Atherosclerosis. Biomedicines. 2023;11(2):384.

- Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's pathology of domestic animals Pathology of domestic animals). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, 2016.

- Natarajan SK, Eapen CE, Pullimood AB, Balasubramanian KA. Oxidative stress in experimental liver microvesicular steatosis: role of mitochondria and peroxisomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1240-1249.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology. 2010;52:774-788.

- Percy DH, Barthold SW, Griffey SM. Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016.

- Pipitone RM, Ciccioli C, Infantino G, et al. MAFLD: a multisystem disease.

Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2023;14:20420188221145549. - Roskams T. Relationships among stellate cell activation, progenitor cells, and hepatic regeneration. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:853-860,ix.

- Sharma D, Hill AE, Christopher MM. Hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia as biochemical markers of disease in companion rabbits. Vet Clin Pathol. 2018;47:589-602.

- Shiomi M. The History of the WHHL Rabbit, an Animal Model of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (I) - Contribution to the Elucidation of the Pathophysiology of Human Hypercholesterolemia and Coronary Heart Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(2):105-118.

- Zhou F, Sun X. Cholesterol Metabolism: A Double-Edged Sword in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021;9.