Signalment:

Note: The viral challenge study and necropsy were performed under biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) conditions. The research was conducted under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 1996. The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

Gross Description:

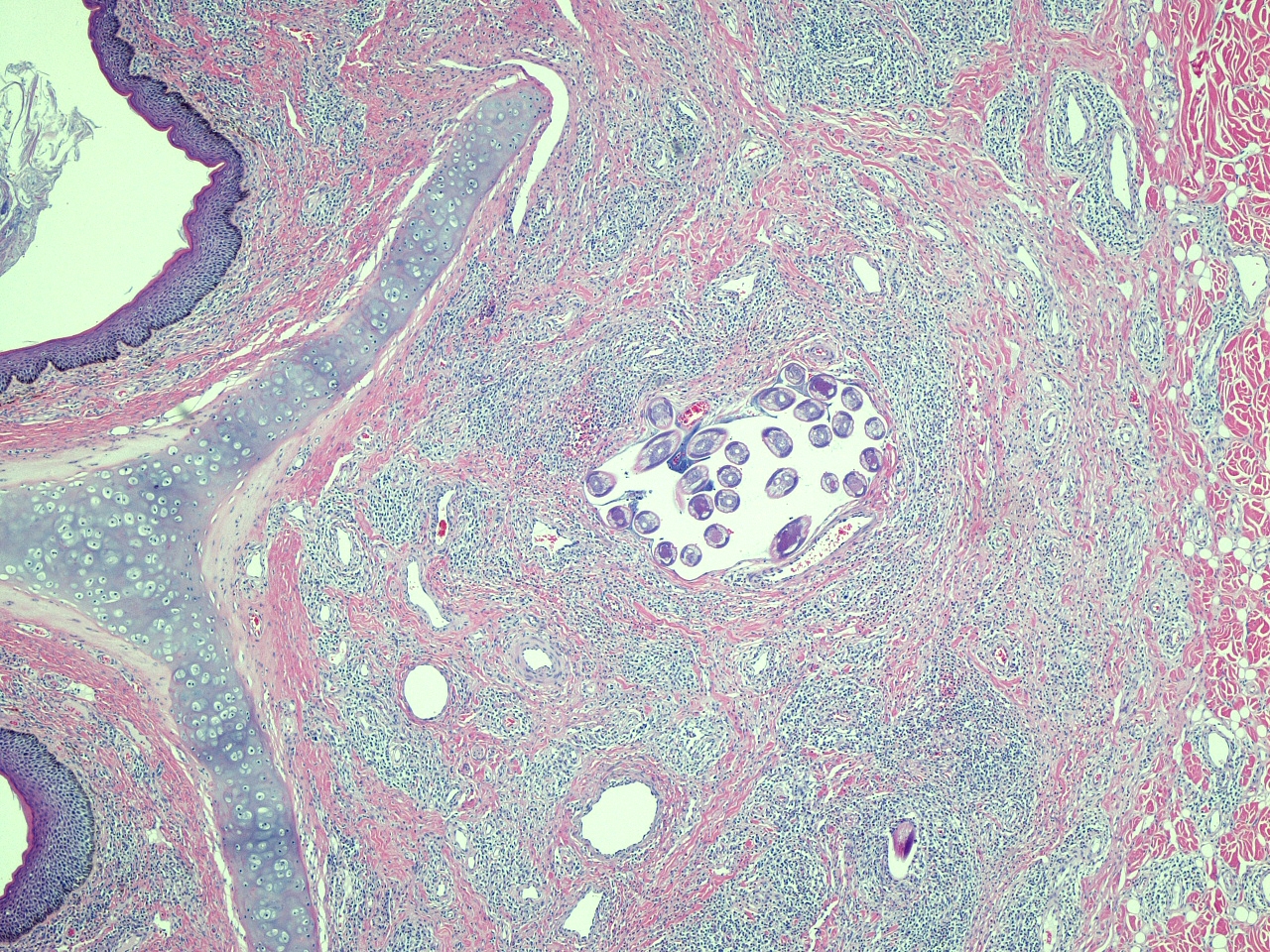

Histopathologic Description:

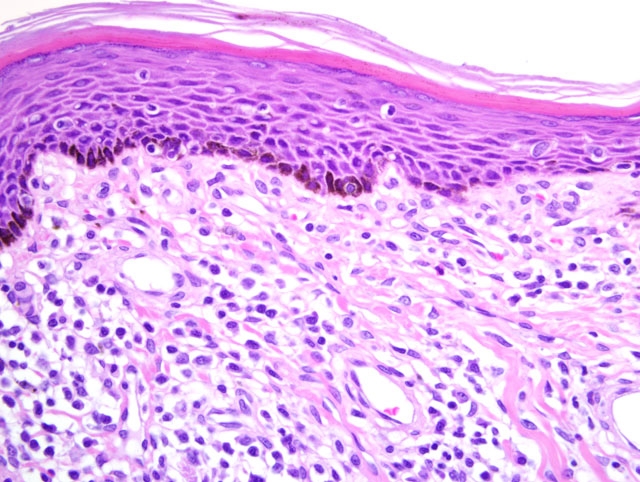

Nasal vestibule: There are multifocal and coalescing infiltrates of moderate numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fewer eosinophils and macrophages within the lamina propria and the submucosa. These inflammatory cell infiltrates usually have a perivascular orientation and often extend into and disrupt the vessel walls. The deep dermis adjacent to the submucosa also has multifocal perivascular infiltrates of similar, but fewer, inflammatory cells. There is multifocal moderate orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis of the mucosal epithelium accompanied by aggregates of keratinized debris and numerous coccoid and bacillary bacteria along the luminal surface of the epithelium. Multifocally, infiltration of the epithelium by low numbers of neutrophils is also present.

Lip: There are multifocal infiltrates of low to moderate numbers of lymphocytes and fewer plasma cells within the submucosal labial glands, often accompanied by atrophy and loss of glandular cells.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Nasal vestibule: Multifocal and coalescing lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic rhinitis, moderate to marked, with mucosal hyperkeratosis and perivascular dermatitis.

2. Lip: Multifocal lymphocytic labial gland adenitis, mild.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

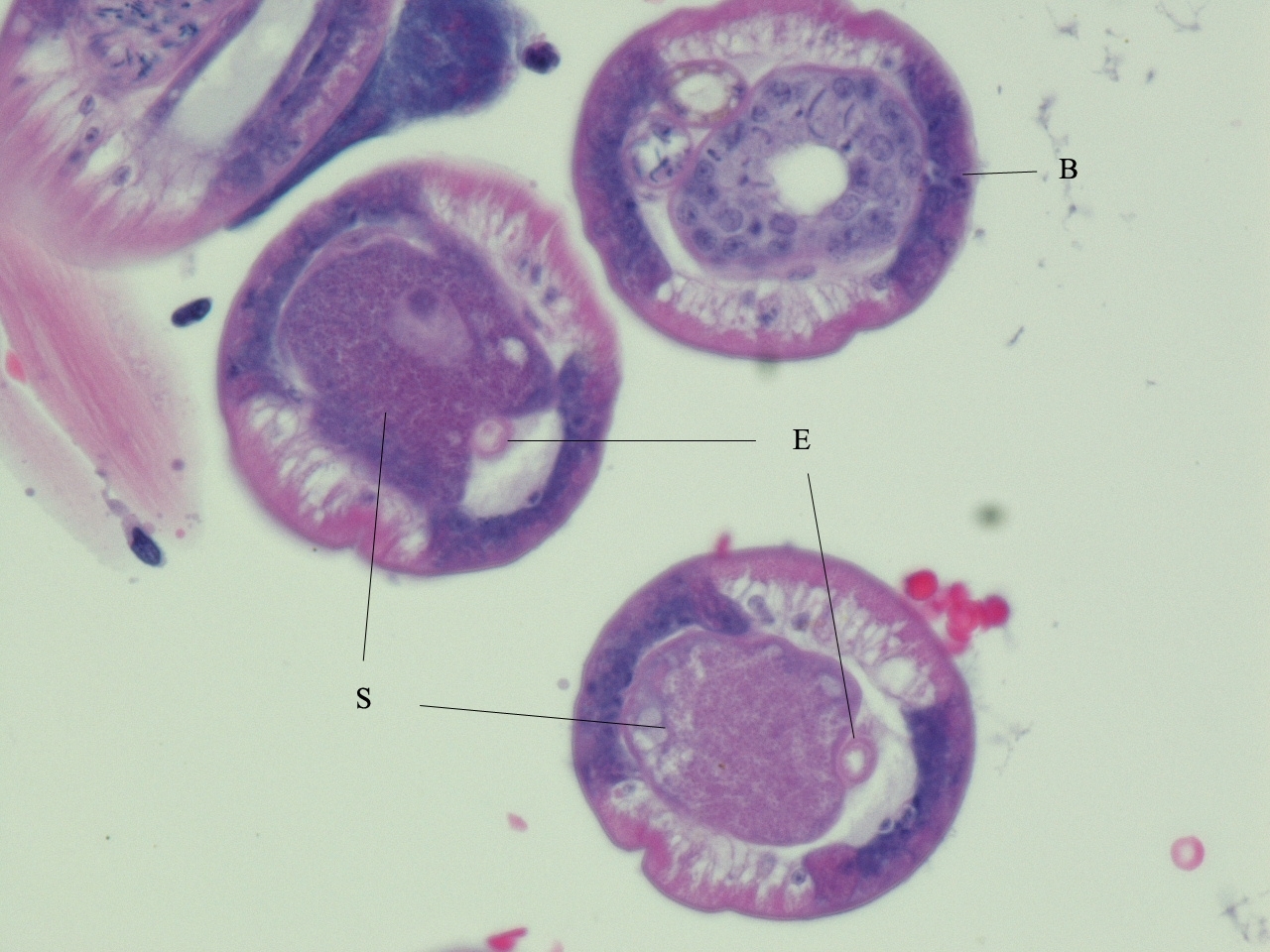

Two species of Anatrichosoma have been described in macaques, A. cynamolgi and A. cutaneum, and each species can infect both cynomolgus and rhesus macaques.(1,3,8,10) The first of these parasite species discovered, A. cutaneum, was initially described in association with significant inflammatory lesions in the skin and subcutis of the hands and feet of rhesus macaques. However, these were apparently aberrant locations for the parasites;(1) the mucosa and submucosa of the nasal vestibule is the normal site of parasitism for both species of worms,(1,3) and infections in this location have not been associated with clinical signs or gross lesions. Differentiation of the two Anatrichosoma species is most reliably accomplished by examination of unfixed eggs and/or intact worms.(3,10)

Surveys of wild-caught macaques have indicated that the prevalence of infection in some free-ranging populations can range as high as 48%.(5) In one report concerning an experimental inhalation toxicity study, the parasites and/or nasal inflammation consistent with Anatrichosoma sp. infection were detected in 27 of 32 (84%) juvenile rhesus macaques.(6)

The full life cycle of these parasites is unknown. Mature female worms are located within the stratified squamous epithelium of the nasal vestibule where they are associated with epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis and varying degrees of inflammation of the epithelium and underlying tissues.(1,6,7) The female worms and released eggs are often present within intra-epithelial tunnels made by the worms. Immature parasites and mature males are usually located in the lamina propria and submucosa and are often intravascular (as in this case).(1,3,7,10) It is postulated that the male worms migrate up to the epithelial layer for mating and then return to the deeper tissues afterwards.(7) Eggs may be released directly by the females into the nasal vestibular lumen or reach the lumen from the intra-epithelial tunnels during epithelial desquamation.

There have been limited and unsuccessful attempts to experimentally infect macaques by direct transmission of the eggs.(10) This has led to speculation that one or more intermediate hosts are required.(9)

Although fecal samples from Anatrichosoma-infected monkeys may contain the parasite eggs, examination of nasal swabs for presence of eggs has been shown to be a more reliable method for ante mortem detection of parasitized individuals.(5)

The inflammation present in the labial glands of this case is mild; this is a common, incidental finding in macaques and is unlikely to be associated with the ebolavirus challenge or the nematode parasitism. At our institution, we routinely include a section of lip in the histology block with the nasal vestibule.

Note: Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations above are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army or Department of Defense.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Haired skin and nasal vestibule: Rhinitis, lymphoplasmacytic, histiocytic, and eosinophilic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with epithelial hyperplasia, orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and perivasculitis.

2. Mucocutaneous junction, lip, minor salivary gland: Sialoadenitis, interstitial, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, chronic, multifocal, mild.

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML, Alcaraz A: Georgis Parasitology for Veterinarians, 8th ed., pp. 225-230, 391-393. Saunders, St. Louis, MO, 2003

3. Chitwood MB, Smith WN: A redescription of Anatrichosoma cynamolgi Smith and Chitwood, 1954. Proc Helmin Soc Wash 25:112-117, 1958

4. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, pp. 40-42. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1999

5. Karr SL, Henrickson RV, Else JG: A survey for Anatrichosoma (Nematoda:Trichonellida) in wild-caught Macaca mulatta. Lab An Sci 29:789-790, 1979

6. Klonne DR, Ulrich CE, Riley MG, Hamm TE, Morgan KT, Barrow CS: One-year inhalation toxicity study of chlorine in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Fundamen Appl Toxicol 9:557-572, 1987

7. Little MD, Orihel TC: The mating behavior of Anatrichosoma (Nematoda: Trichuroidea). J Parasit 58:1019-1020, 1972

8. Reardon LV, Rininger BF: A survey of parasites in laboratory primates. Lab An Care 18:577-580, 1968

9. Ulrich CP, Henrickson RV, Karr S: An epidemiological survey of wild caught and domestic born rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) for Anatrichosoma (Nematoda: Trichinellida). Lab An Sci 31:726-727, 1981

10. Wong MM, Conrad HD: Prevalence of metazoan parasite infections in five species of Asian macaques. Lab An Sci 28:412-416, 1978