WSC 2023-2024, Conference 20, Case 3

Signalment:

5-year-old female Holstein (Bos taurus)

History:

This adult cow was admitted to the clinic with sudden onset of weakness, abdominal pain, and bloody feces. In the preliminary report, an embryo wash was performed three weeks prior to submission. A suspected diagnosis of hemorrhagic bowel syndrome was made. The animal underwent abdominal surgery (manual blood clot dissolution) and symptomatic treatment; however, the cow spontaneously died the following night.

Gross Pathology:

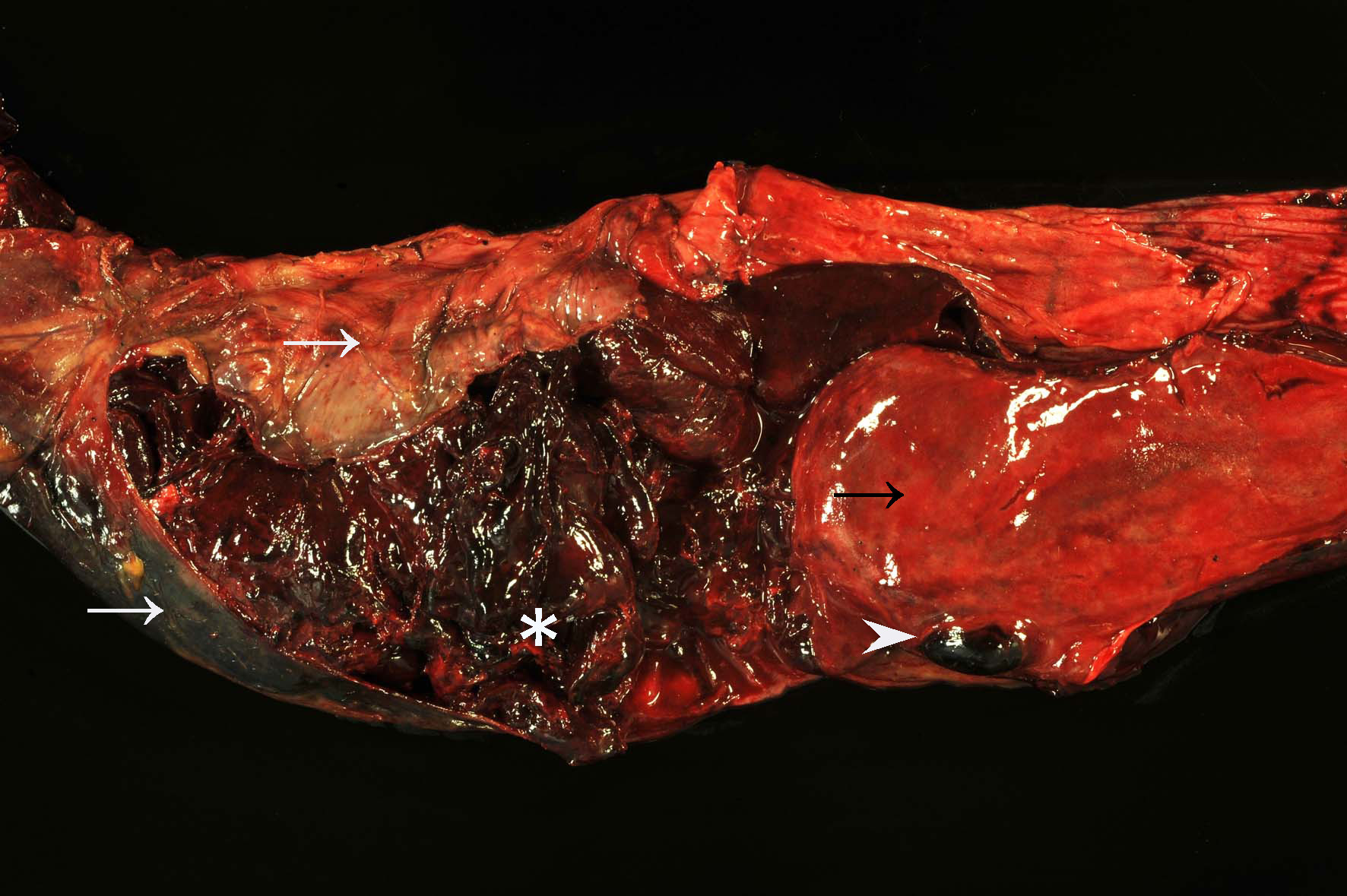

The distal jejunum was distended and filled with coagulated blood. Multifocal intramural hematomas (approximately 3 x 2 x 1 cm) as well as blood coagula adherent to the intestinal mucosa (approximately 40 cm length, on average) were present in the affected segment.

Orally to the described lesion, the jejunal mucosa was diffusely bright red with multifocal dark red areas and multiple, up to 1 mm in diameter large, submucosal hematomas. Intestinal contents in the cecum and colon were dark-red, viscous, and admixed with large amounts of coagulated blood, whereas the rectum was empty. Additionally, there were multifocal petechial hemorrhages on the serosal surfaces of internal organs. A small amount of serous, red fluid was found in the greater omentum. Moderate pharyngeal edema was present. Additionally, the liver was diffusely soft and beige-yellow with mildly rounded edges. Moreover, the nose and lungs showed diffuse, moderate hyperemia and the lung also a mild, diffuse, alveolar edema.

Laboratory Results:

Salmonella spp. were not isolated from a small intestine sample. Bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine herpesvirus-1 were not isolated in cell culture. PCR for Bluetongue virus and bovine herpesvirus-1 were negative as well. The test for the proteinase K-resistant prion protein was negative.

Immunohistochemistry on smooth muscle actin using the avidin-biotin peroxidase technique revealed a splitting of the lamina muscularis mucosae with accumulation of blood between the muscle layers.

Microscopic Description:

Approximately 90% of the tissue section shows a separation of the mucosa from the submucosa due to extensive submucosal hematoma formation. The overlying mucosal layer displays moderate necrosis but also autolysis with bright eosinophilic cellular debris and multifocal dilated villus lacteals. Furthermore, the mucosal layer is focally eroded. Also moderate numbers of rod-shaped bacteria can be observed on the luminal surface as well as mild fibrin formation in between the separated muscle layers.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Jejunum: Segmental mucosal necrosis and intramural hematoma formation, bovine.

Contributor’s Comment:

Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS), first described in the early 90s, is a sporadic, often fatal disorder characterized by acute extensive segmental jejunal hemorrhage and intramural hematoma formation predominantly affecting adult dairy cattle.2,3 A significant proportion of the affected animals are of Brown Swiss breed.2

Among other clinical symptoms, notable blackberry jelly-like blood clots within feces, decreased milk production, tachycardia and/or palor of mucous membranes are commonly reported.3 Post-mortem findings usually include one or more short jejunal segments with severe intramural hemorrhage/hematoma formation, which may completely or partially obstruct the intestinal lumen.5 These findings were also observed in this case. Intraluminal blood clots were mostly observed at the areas of ruptured mucosa. The histologic findings in this case are consistent with previously described lesions.1,2 A mild to moderate vasculitis, which has been described in some cases, was not observed in the presented case.1,2,5

The etiology and pathogenesis of this disorder is currently unknown. Several infectious factors, including the contribution of Clostridium perfringens or Aspergillus fumigatus, have been suspected, but no statistically significant relations have been detected so far.5 Thus, the observed bacteria are more likely secondary to the progressing disease and autolysis.5 Due to dilated villus lacteals and the moderate to severe submucosal vasculitis observed in other reported cases, it has been hypothesized that an initial vasculopathy or abnormal lymphatic function may be responsible for the prominent dissecting hemorrhages, but these theories have not been confirmed.1

Recent findings indicate that hemorrhages appear to originate within the lamina muscularis mucosa (Lmm) and lead to the eruption of the mucosa with severe intraluminal bleeding and blood clot formation within the jejunum.2 The splitting of the Lmm potentially leads to the rupture of the many arterioles that course through the Lmm and supply blood from the submucosa to the subepithelial capillary beds.2 This process is further accelerated by the arterial blood pressure, which results in a “zipper-mechanism” characterized by expanding, dissecting hemorrhages.2

In the present case, an immunohistochemical stain for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) was performed which identified SMA-positive fragments of Lmm beneath the mucosa adjacent to the hemorrhage as well as on the contralateral side framing the tunica muscularis. Furthermore, immunohistochemical cytokeratin staining visualized the intestinal epithelium. Overall, the described findings correspond to previously reported cases and support the assumption that the fragmentation of the Lmm, which surrounds the hematoma, is a consequence of the intramuscular hematoma formation.2 The cause of the spontaneous detachment of the Lmm layers remains unclear. Mucosal necrosis is considered as a change secondary to the resulting ischemia rather than a primary inflammatory entity such as described in hemorrhagic enteritis.2

Shock gut syndrome and hemorrhagic enteritis should be considered as differential diagnoses. The “shock gut” syndrome is most common in dogs and results in decreased perfusion of the intestine. It is morphologically characterized by congestion of intestinal mucosa, as well as reddish intestinal content.5 Hemorrhagic enteritis in adult cattle can be caused by infectious (Salmonella spp., coronaviruses) and non-infectious factors (arsenic, oak, oleander poisoning) and manifests as reddish intestinal content, congested mucosa and diarrhea.5

Cattle affected by HBS often show acute onset of poor general condition, clotted blood in the feces, and sudden death.1 The treatment can be symptomatic or surgical; however, in either case the prognosis is rather poor with most animals dying or being euthanised.5

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology

University of Veterinary Medicine

Hannover, Germany

http://www.tiho-hannover.de/kliniken-institute/institute/institut-fuer-pathologie/

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Mural hemorrhage, segmental, acute, diffuse, severe.

JPC Comment:

The typical gross and histologic lesions of hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS), also known as jejunal hemorrhage syndrome, have been well described in the veterinary literature and are nicely summarized by the contributor.1-3 Other common causes of intraluminal intestinal hemorrhage include intussusception, volvulus, salmonellosis, bovine viral diarrhea virus infection, coccidioisis, coagulopathies, and intestinal foreign bodies; however, HBS differs from these differentials by the presence of large intraluminal or intramural blood clots that result in small intestinal obstruction, most commonly in the jejunum.2,3

Hematologic parameters of HBS-affected cattle largely reflect the acute, hemorrhagic nature of the disease. There is usually a neutrophilia and hyperglycemia, both attributable to the release of inflammatory cytokines and endogenous, stress-related steroid release.3 The physical obstruction of the proximal intestine results in sequestration of abomasal secretions, leading to electrolyte abnormalities, most commonly hypochloremia and hypokalemia.3 Liver enzymes, such as sorbitol dehydrogenase and gamma-glutamyltransferase may be elevated due to gastrointestinal obstruction or stasis and subsequent absorption of bacteria and toxins from the affected area of intestine.3 Other abnormalities include increased blood urea nitrogen, attributed to intraluminal digestion of blood, hyperlactatemia, and acidemia; inconsistent calcium and magnesium derangements have been reported.3,4

The acute nature of the disease and the poor prognosis despite treatment make HBS a source of high economic losses, and efforts are underway to determine the cause of the disease, the existence of any ante-mortem biomarkers, and the most promising treatments for acutely affected animals. Recent efforts have begun mining biosensor data, routinely collected from dairy cows to monitor estrus and milk yields, to determine if any clinically silent premonitory signs can be identified. The first such report on these efforts found that decreases in rumination time and activity, rumen mobility, rumen temperature, and milk yields preceeded clinically evident signs, offering a potential early alert mechanism to identify and treat dairy cows early in the course of disease.4

Conference participants appreciated the unique, striking subgross histologic appearance of this case and discussion focused largely on whether the mucosal changes represent necrosis or autolysis. Participants believed that the changes were largely autolytic due to the lack of visible thrombi in section and the fact that tissue in less-affected, normal areas of the section had a similar histologic appearance. Participants also reviewed a smooth muscle actin immunohistochemical stain which illustrated the dramatically thin rim of muscularis mucosae lining the hematoma and nicely illustrated the splitting of this histologic layer as described in a recently published article characterizing this entity.2

The moderator noted that, though HBS cases have become rare recently, his diagnostic lab has historically seen multiple cases of HBS per week. The moderator shared a wealth of gross and histologic HBS images from this historic caseload that delighted conference participants. The moderator challenged the textbook clinical presentation of blood clots in the feces. In his experience, most animals die of intestinal obstruction caused by the intramural hematoma; it is only if the animal survives the acute period that the hematoma ruptures the mucosa and blood appears in the manure.

References:

- Adaska JM, Aly SS, Moeller RB, et al. Jejunal hematoma in cattle: a retrospective case analysis. J Vet Diagn Inv. 2014; 26 (1):96 -103.

- De Jonge B, Pardon B, Goossens E, et al. Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle: Gross, histological, and micro-biological characterization. Vet Pathol. 2023;60(2):235–244.

- Dennison AC, VanMetre DC, Callan RJ, et al. Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle: 22 cases (1997-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221(5):686-689.

- Ha SM, Kang SG, Jung MY, et al. Retrospective study using biosensor data of a milking Holstein cow with jejunal haemorrhage syndrome. Vet Med (Praha). 2023; 68(9):375-383.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animal. 6th ed. Vol. 2. Elsevier; 2016:1-257.