Signalment:

On initial neurologic examination, the animal had a left head turn and tilt, thoracolumbar kyphosis and extensor rigidity of the pelvic limbs. The animal was tetraplegic but could move all limbs when supported ventrally. The animal would alligator roll to the left when attempting to stand. Placing responses and hopping were absent in all four limbs. Muscle tone was increased in all four limbs, most markedly in the pelvic limbs. Spinal reflexes were increased in the pelvic limbs (with a crossed extensor). Menace response was absent in both eyes and there was a resting ventrolateral strabismus in the left eye. Pain could be elicited on palpation over the calvarium and cervical spine. Complete blood count, chemistry profile and preprandial and postprandial bile acids testing showed no significant abnormalities.

The animals neurologic status improved somewhat after treatment with prednisone, and the animal was no longer painful. Two weeks after starting the steroid medication, a neurologic examination showed no change to the cranial nerve deficits and a continued head tilt and turn; however, the animal was able to walk again (with tetraparesis and tetrataxia). The animal continued to show improvement on steroids for six weeks but then began to show worsening neurologic symptoms. At final examination, the animals demeanor was dull, and it was unable to stand with or without support. Proprioception was decreased to absent in all four limbs. In addition to previously observed cranial nerve symptoms, the animal now had mild anisocoria (left > right) and positional slow rotary nystagmus. The owner elected euthanasia.

Gross Description:

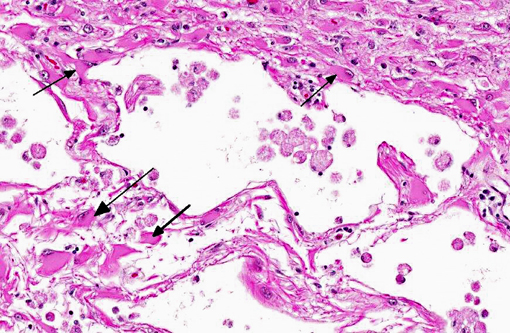

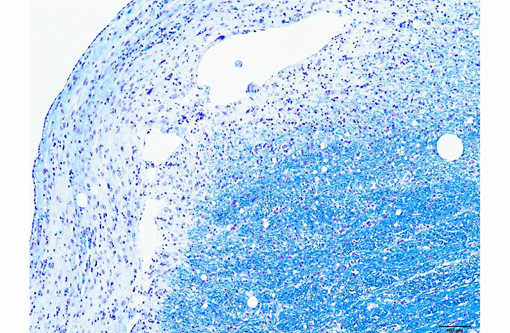

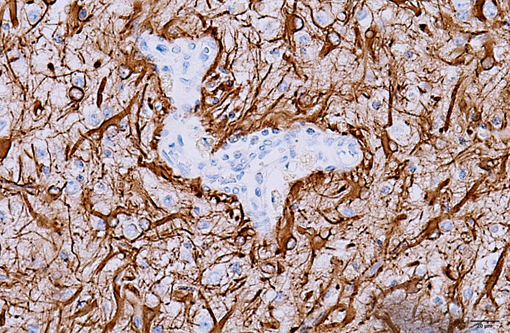

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

CBC:

| Value | Reference Range | Units | |

| HCT | 55.8% | 35-52% | |

| MCHC | 31.3 | 32.0-36.0 | g/dL |

| Eosinophils | 0.081x103 | 0.1-1.0 x103 | /μL |

- Anisocytosis: 1+

- Polychromasia: rare

- Target cells: 4+

Chemistry:

| Value | Reference Range | Units | |

| Globulin | 2.6 | 2.7-4.4 | g/dL |

| Alb/Glob ratio | 1.3 | 0.6-1.1 | |

| ALT | 93 | 8-65 | U/L |

| Total T4 | 14.3 | 15.0-48.0 | nmol/L |

| Bile acids (preprandial) | 15.5 | 0.0-7.5 | nmol/L |

| Bile acids (postprandial) | 16.0 | 0.0-25.0 | nmol/L |

Microbiology:

Aerobic culture:

- Brain: Pasteurella multocida few

- Brain: Alpha strep non-Enterococcus rare

- Brain: Escherichia coli - rare

Anaerobic culture:

- Brain: Clostridium perfringens - v. few

- Brain: Prevotella - few

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

NLE is commonly grouped with Necrotizing Meningoencephalitis (NME) or pug dog encephalitis(7) in veterinary literature. While breed predilection and lesion topography vary between the two diseases (NME affects gray and white matter primarily in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and thalamus,(4) while NLE affects the cerebra and brainstem), the hallmark of both diseases is lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis and bilateral, asymmetric, cerebral necrosis.(7) There is some debate as to whether these diseases are two distinct entities or one disease with a similar pathogenesis but histopathologic differences as a result of minor genetic differences between breeds, modifying genes and/or variations in antigenic exposures.(7)

NLE was first described in Yorkshire terriers in 1993,(9) and has since been diagnosed in French bulldogs as well.(6,8) It primarily affects young adult dogs, with a mean age of onset of 4.5 years (range, 4 months to 10 years old).(8) It appears to affect male and female dogs equally.(9) Clinical signs on initial presentation are referable to the location of the cerebral lesions, and commonly include visual deficits or blindness, depression, seizures, circling, ataxia and head tilt.(6) Conventional treatment is with immunosuppressive doses of glucocorticoids. Survival after diagnosis varies between 3 and 18 months(2) and the disease is invariably progressive and fatal.

The etiology of NLE is poorly understood. No infectious agents have ever been identified in association with NLE; PCR screening in dogs with histopathologic diagnoses of NLE and NME for the presence of degenerate herpesvirus, adenovirus, and canine parvovirus viral proteins have revealed no viral proteins,(1) and IHC staining for Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum are routinely negative. However, negative PCR results for viruses does not rule out the possibility of a viral trigger for the disease via molecular mimicry, or the possibility that a pathogen is present at undetectable levels in the presence of a self-perpetuating immune response, a phenomenon that has been described for flavivirus infections.(7) Genetics may play a role in pathogenesis, as the disease is breed specific, and a strong familial inheritance pattern was detected in pugs with NME.(7) There is likely an immune-mediated component to NLE, as evidenced by the variable but generally positive response of the disease to treatment with glucocorticosteroids. In one case report of NLE, major infiltration of necrotic areas by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, IgG producing plasma cells, macrophages and microglial cells was identified, suggesting a possible delayed T-cell immune response in the pathogenesis of the disease.(3) It is most likely that NLE is a multifactorial disorder caused by an as yet unknown combination of the factors above.

Diagnosis of NLE can be made on a combination of factors: age, breed affected, clinical signs that can be localized to the cerebra and brainstem, and a chronic, progressive course should all be considered when making a diagnosis. MRI imaging can be a very helpful diagnostic tool, and allows the diagnosis of NLE with a high degree of suspicion based on lesion localization, lesion appearance in different sequences and contrast enhancement.(11) Protein levels and cell counts in the CSF may also be increased in cases of NLE,(5,6) but this is a non-specific finding and should only be used in conjunction with the factors above in making a diagnosis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The microscopic lesions in this case, particularly their cavitating nature and specific location within the white matter, are most consistent with the condition known as necrotizing leukoencephalitis of Yorkshire terriers (NLE). Conference participants speculated that the mild perivascular and leptomeningeal inflammation was likely a reactive change secondary to marked necrosis and that the presence of hydrocephalus ex vacuo was probably due to the filling of the large pseudocysts with CSF.Â

References:

1. Jung D, Kang B, Park C, Yoo J, Gu S, Jeon H, et al. A comparison of combination therapy (cyclosporine plus prednisolone) with sole prednisolone therapy in 7 dogs with necrotizing meningoencephalitis. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69(12):1303-1306.

2. Kuwamura M, Adachi T, Yamate J, Kotani T, Ohashi F, Summers B. Necrotising encephalitis in the Yorkshire terrier: a case report and literature review. J Small Anim Prac. 2002;43:459-463.

3. Lezmi S, Toussaint Y, Prata D, Lejeune T, Ferreira-Neves P, Rakotovao F, et al. Severe necrotizing encephalitis in a Yorkshire terrier: topographic and immunohistochemical study. J Vet Med Assoc. 2007;54:186-190.

4. Park E, Uchina K. Nakayama H. Comprehensive immunohistochemical studies on canine necrotizing meningoencephalitis (NME), necrotizing leukoencephalitis (NLE), and granulomatous meningoencephalitis (GME). Vet Pathol. 2012;49(4):682-692.

5. Schatzberg S, Haley N, Barr S, de LaHunta A, Sharp N. Polymerase chain reaction screening for DNA viruses in paraffin-embedded brains from dogs with necrotizing meningoencephalitis, necrotizing leukoencephalitis, and granulomatous meningoencephalitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:553-559.

6. Spitzbarth I, Schenk H, Tipold A, Beineke A. Immunohistochemical characterization of inflammatory and glial responses in a case of necrotizing leukoencephalitis in a French bulldog. J Comp Path. 2010;142:235-241.

7. Talarico L, Schatzberg S. Idiopathic granulomatous and necrotising inflammatory disorders of the canine central nervous system: a review and future perspectives. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:138-149.

8. Timmann D, Konar M, Howard J, Vandevelde M. Necrotizing encephalitis in a French bulldog. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48:339-342.

9. Tipold A, Fatzer R, Jaggy A. Necrotizing encephalitis in Yorkshire terriers. J Small Anim Pract. 1993;34:623-628.

10. Vernae KM, Runstadler JA, Brown EA, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies a mutation in the thiamine transporter 2 (SLC19A3) gene associated with Alaskan husky encephalopathy. PLOS One. 2013;8(3):e57195.

11. von Praun F, Matisek K, Grevel V, Alef M, Flegel T. Magnetic resonance imaging and pathologic findings associated with necrotizing encephalitis in two Yorkshire terriers. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 2006;47(3):260-264.