WSC 2023-2024 Conference 1, Case 3

Signalment:

4-year-old, female, Southern Pre-alps sheep (Ovis aries).

History:

Several animals of a herd showed neurologic symptoms including amaurosis for several weeks. Some animals progressed to death, others were euthanized and submitted for necropsy. This case was referred (alive) to the veterinary hospital for pedagogic purposes. The animal presented depressed, with a left head tilt, circling to the left, and a hypermetric forelimb gait. MRI showed a 4 cm liquid mass in the left cerebral hemisphere compressing the lateral ventricle. The mass was surgically removed; 2 days later the animal was euthanized because of status epilepticus.

Microscopic Description:

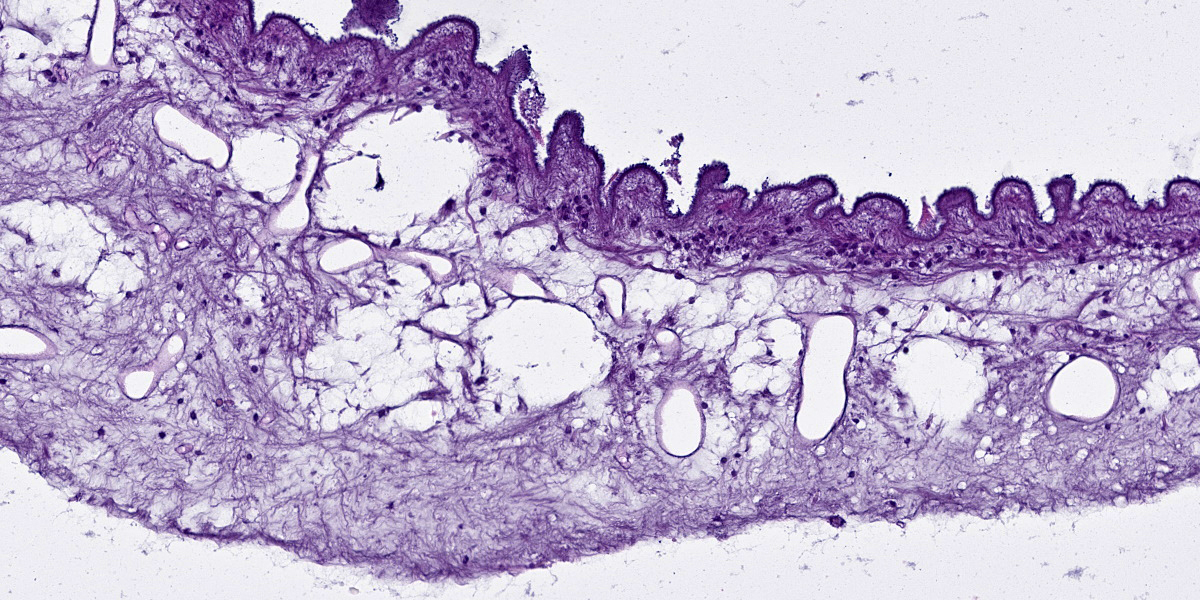

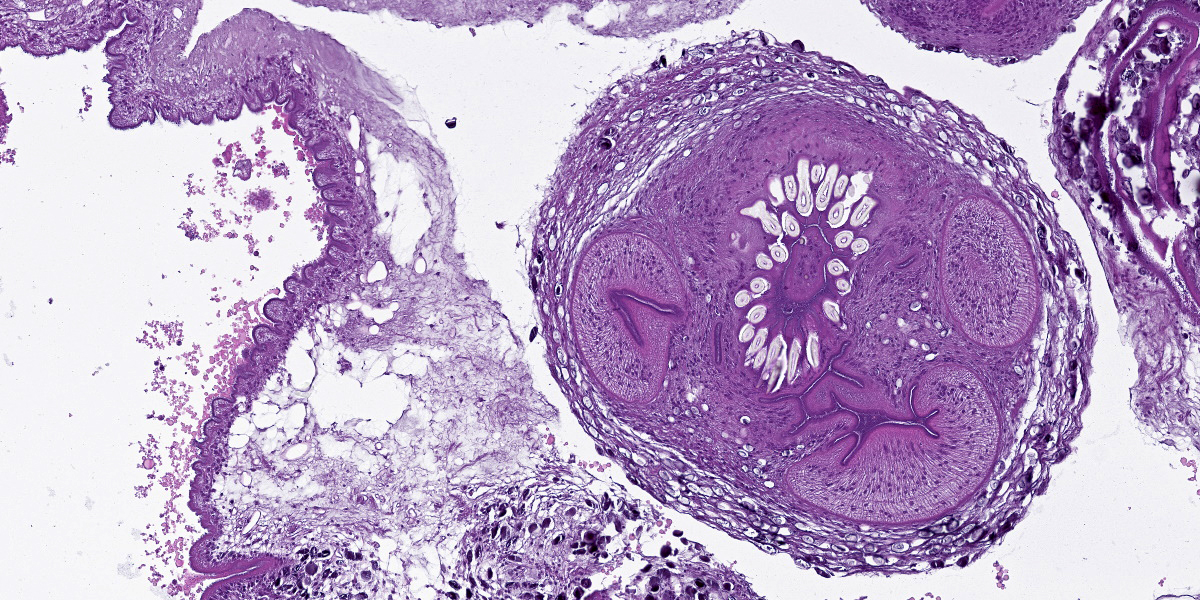

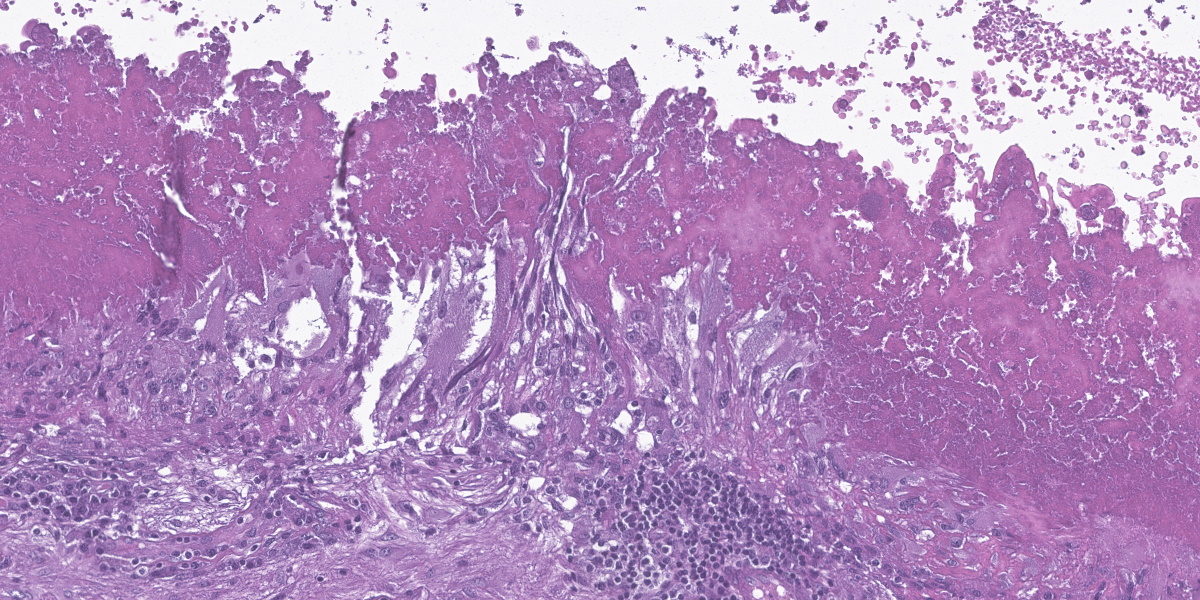

Cerebrum: The cerebral parenchyma is characterized by a compressive cystic nodular lesion lined by diffuse, moderate to severe inflammation composed of a large number of lymphocytes and plasma cells surrounding several macrophages, epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells with up to 11 nuclei. Multifocally, between the granulomatous inflammation and the cyst wall there is a large amount of amorphous eosinophilic material and cellular debris (liquefactive necrosis). The cyst wall is composed of a thin outer undulating hyaline layer with microtriches (microvilli) and an inner layer of areolar tissue (germinative membrane). Arising from the germinative membrane, multiple larval metazoan parasites are visible (protoscolices). They are up to 1mm in diameter, lined by an eosinophilic smooth, ridged tegument, which is also visible inside the parasite (inverted tegument). They contain a solid parenchyma with many basophilic to clear oval, up to 15µm basophilic bodies (calcareous corpuscles), an invaginated scolex containing multiple anterior suckers composed of muscular rings comprising radial striations of muscle fibers, and a rostellum with multiple birefringent hooks. Digestive tract, reproductive tract, and pseudocoelom are absent. Lymphocytes and plasma cells are multifocally visible in perivascular areas (lymphocytic cuffs).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Cerebrum: Encephalitis, granulomatous, focally extensive, chronic, moderate with intralesional coenurus protoscolices.

Contributor’s Comment:

Coenurus cerebralis is the intermediate stage of Taenia multiceps. C. cerebralis has a worldwide distribution, affecting primarily sheep and goats, though it has been described in other animals, including cattle, buffalos, yak, horse and pig.4

T. multiceps has an indirect life cycle. Canids, including domestic dogs, are definitive hosts. Adult worms, up to 100 cm in length, live in the small intestine of definitive hosts, who shed embryonated eggs and gravid proglottids in their faeces, contaminating pasture and water. When eaten by intermediate hosts, eggs release oncospheres (larvae) in the intestine. The oncospheres burrow through the intestinal wall, enter the circulation and migrate to the central nervous system, most often the cerebrum, where they form one or more unilocular bladder cysts.4 Cerebral coenurosis is caused by Coenurus cerebralis, the larval stage of T. multiceps. The cysts grow over 6-8 months, eventually causing clinical signs.4 T. multiceps protoscolices develop from the inner cyst wall and can reproduce asexually so that each coenurus may contain up to 400-500 scolices. The life cycle is completed when a definitive host eats the coenurus, releasing protoscolices, which attach to the intestinal wall and develop into adults in 42 to 60 days. This requires canids to have access to the brain of an infected animal.4

The cerebral clinical disease is commonly referred as “sturdy” or “gid.” Acute and chronic forms exist. The acute disease is caused by larval migration through the brain. Its severity depends on the number of ingested eggs and migrating parasites. The chronic form is more commonly observed and it occurs in older animals.4 It is due to cyst development in the brain, and less frequently in the spinal cord, causing parenchymal compression which leads to significant neurological signs and death.4 Clinical signs of C. cerebralis include ataxia, blindness, head pressing and circling towards the affected side of the brain.4,5,7 Signs progress to coma and death if untreated. Spinal cord lesions cause progressive hind limb paresis/paralysis.4,5 Diagnosis is made using a combination of clinical signs, neurological examination, ultrasound and necropsy. 4

Coenurus has been rarely reported in extra-cerebral locations. These reports are mostly from Asian countries. Non-cerebral coenurus has been described in the skeletal muscle, fascia, adipose tissue, lungs, peritoneum and pelvic cavity of sheep and goats.1,4 Non-cerebral coenurus is often asymptomatic and only detected at slaughter, but may cause muscle pain.4

Grossly, C. cerebralis is composed of thin walled, fluid-filled, unilocular cysts up to 7cm in diameter. The cyst walls have multifocal white nodules comprising clusters of protoscolices.6 Cysts more commonly occur in the cerebrum than in cerebellum or spinal cord. The cysts cause cerebral compression and can be responsible for hydrocephalus and cerebral or cerebellar herniation.4,7

Histologically, the cyst wall comprises an external eosinophilic layer with basophilic microtriches (microvilli) and an inner germinative layer made up of areolar tissue.2 Multiple T. multiceps protoscolices arise from invaginations of the cyst wall. Protoscolices have four muscular anterior suckers, a rostellum with up to 34 hooks arranged in 2 rows, and an eosinophilic invaginated tegument. They also have standard features of cestodes including a parenchyma containing calcareous corpuscles, no pseudocoelom and no digestive or reproductive tract.6

Changes to the cerebral/cerebellar parenchyma range from mild to severe liquefactive necrosis and lymphocytic/ granulomatous inflammation with an infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and foreign-body multinucleated giant cells. Accompanying changes include neuronal degeneration and necrosis, satellitosis, neuronophagia, demyelination, gliosis and formation of microglial nodules, non-suppurative meningitis and meningeal hyperaemia and oedema.2,6

Humans are rarely infected. The main location of intermediate forms in humans is the subcutaneous tissue, but cerebral coenurosis is also described.4

Contributing Institution:

VetAgro Sup

Campus Vétérinaire

Anatomie Pathologique

89 Av. de l’Europe

63370 Lempdes, France

www.vetagro-sup.fr

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Encephalitis, granulomatous, focally extensive, severe, with coenurus.

JPC Comment:

Cerebral coenurosis is thought to have been reported for the first time by Hippocrates, who described a condition causing epilepsy in sheep and goats that was characterized by an excess of fluid in the brain.8 More recently, studies from 1656 and 1724 reported the presence of water-filled sacs or bladders in sheep and cattle, remarking that these bladders were frequent causes of vertigo and death in affected animals.8 It took until 1853, and feeding cysts taken from infected brains to unsuspecting dogs, to work out the life cycle that the contributor so nicely details.

Today, while coenurosis is reported sporadically in sheep and goats in many European countries (with a relatively high prevalence in Sardinia), the disease is a major endemic disease of small ruminants in the Middle East, particularly in Turkey, Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan.8 In this group, prevalence rates range from 2.9% of Jordanian sheep to 22.8-23.68% of Iraqi sheep and goats.8 A wide range of prevalence is reported in Africa, from a low of 4-8% prevalence in Ethiopian sheep and goats to 42.1% in Tanzanian sheep and goats.8 The disease burden borne by animals and farmers in these regions is significant, and transmission is difficult to control given that wild canids and herding dogs have the ability to travel and spread eggs and proglottids widely.

Infection prevention in endemic areas focuses heavily on educating farmers about proper sanitation and carcass disposal. In Sardinia, Italy, a recent novel preventive measure featured controlled feeding stations, accessible only to birds, where carrion and offal were fed to vultures.8 Though not yet currently commercially available, vaccination against coenurosis is under development, with the first successful field test of a vaccine based on an oncosphere secretory antigen conducted in Sardinia in 2009.9 Once neurologic signs of coenurosis are manifest, treatment options include antihelminthic treatments such as praziquantel, and surgical removal, which is frequently successful though uncommonly performed.

As the contributor notes, cerebral coenurosis is zoonotic and humans may become infected by ingesting eggs present in the feces of definitive hosts.3 Once ingested, oncospheres hatch from the eggs, penetrate the intestinal wall, and travel via the circulation to target organs, including the brain, eyes, and muscle tissue.3 Luckily, such transmission are rare, with only approximately 40 reported human cases; nevertheless, for those unlucky few, treatment requires invasive treatments with results as generally unsatisfactory as in other species.3

Conference discussion focused on the general approach to histologic evaluation of parasites. The moderator emphasized that the ability to recognize the broad category of parasite, such as cestode, trematode, or nematode, was often sufficient to get to a diagnosis when coupled with host species and anatomic location.

References:

- Amrabadi O, Oryan A, Moazeni M, Shari-Fiyazdi H, Akbari M. Histopathological and molecular evaluation of the experimentally infected goats by the larval forms of Taenia multiceps. Iran J Parasitol. 2019 Mar;14:95–105.

- El-Neweshy MS, Khalafalla RE, Ahmed MMS, Al Mawly JH, El-Manakhly E-SM. First report of an outbreak of cerebral coenurosis in Dhofari goats in Oman. Braz J Vet Parasitol. 2019 Aug 1;28(3):479–488.

- Labuschagne J, Frean J, Parbhoo K, et al. Disseminated human subarachnoid coenurosis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7 (12):405.

- Oryan A, Akbari M, Moazeni M, Amrabadi OR. Cerebral and non-cerebral coenurosis in small ruminants. Trop Biomed. 2014 Mar;31:1–16.

- Ozmen O, Sahinduran S, Haligur M, Sezer K. Clinicopathologic observations on Coenurus cerebralis in naturally infected sheep. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2005 Mar;147:129–134.

- Rahsan Y, Nihat Y, Bestami Y, Adnan A, Nuran A. Histopathological, immunohistochemical, and parasitological studies on pathogenesis of Coenurus cerebralis in sheep. J Vet Res. 2018 Mar; 62:35-41.

- Scott PR. Diagnosis and treatment of coenurosis in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2012 Sep 30;189:75-78.

- Varcasia A, Tamponi C, Ahmed F, et al. Taenia multiceps coenurosis: a review. Parasites & Vectors. 2022;15:84.

- Varcasia A, Tosciri G, Sanna, Coccone GN, et al. Preliminary field trial of a vaccine against coenurosis caused by Taenia multiceps. Vet Parasitol. 2009 Jun 10;162:285-289.