Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 7

October 18th, 2017

CASE III: S9004764 (JPC 4019378).

Signalment: 7-week-old, male, Holstein calf, Bos taurus, bovine.

History: A live, 7-week-old, male calf with history of diarrhea, knuckling of the fetlocks, incoordination and stiffness was submitted for necropsy. Some animals in the group showed dyspnea and coughing. Animals were treated with a broad spectrum antibiotic for 4 days.

Gross Pathology: The calf was in good nutritional condition. The abdomen was moderately distended with gas. Tissues were in good state of postmortem decomposition. The forestomachs and abomasum contained a mixture of ingested feed (grain and green forage). There was about 3 liter of straw-colored fluid with fibrin strands in thoracic and abdominal cavities; thick loosely-adherent sheets of yellow fibrin on serous surfaces; and copious amounts of yellowish fibrinous exudates in multiple joints (polyarthritis). Three other in-contact calves had similar necropsy findings

Laboratory results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

Aerobic culture from liver yielded mixed coliforms

Salmonella culture on the colon and liver was negative

Chlamydia culture on tissue pool was negative (guinea pig inoculation, chicken embryos and cell culture).

Virus isolation on tissue pool (lung, brain, spleen) was negative

Immunofluorescent test for Chlamydia on the liver and spleen was negative

Immunofluorescent test for bovine corona virus, IBR, BVD was negative

Immunology for IBR was negative (1:4); and BVD was 1:32.

Heavy metal screen, selenium (liver) and cholinesterase (brain) had normal background levels.

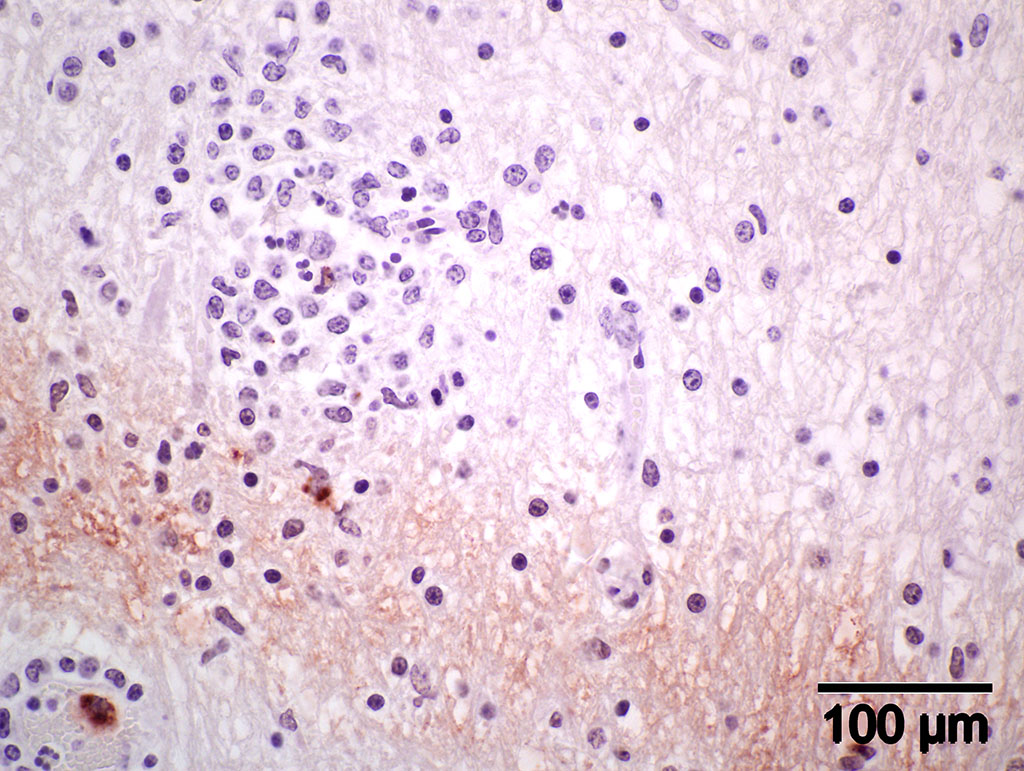

Immunohistochemistry using genus-specific Chlamydia antiserum on brain and liver sections from parafinized tissue blocks (archived for 22 years): Positive for Chlamydia (new name, Chlamydophila) elementary bodies.

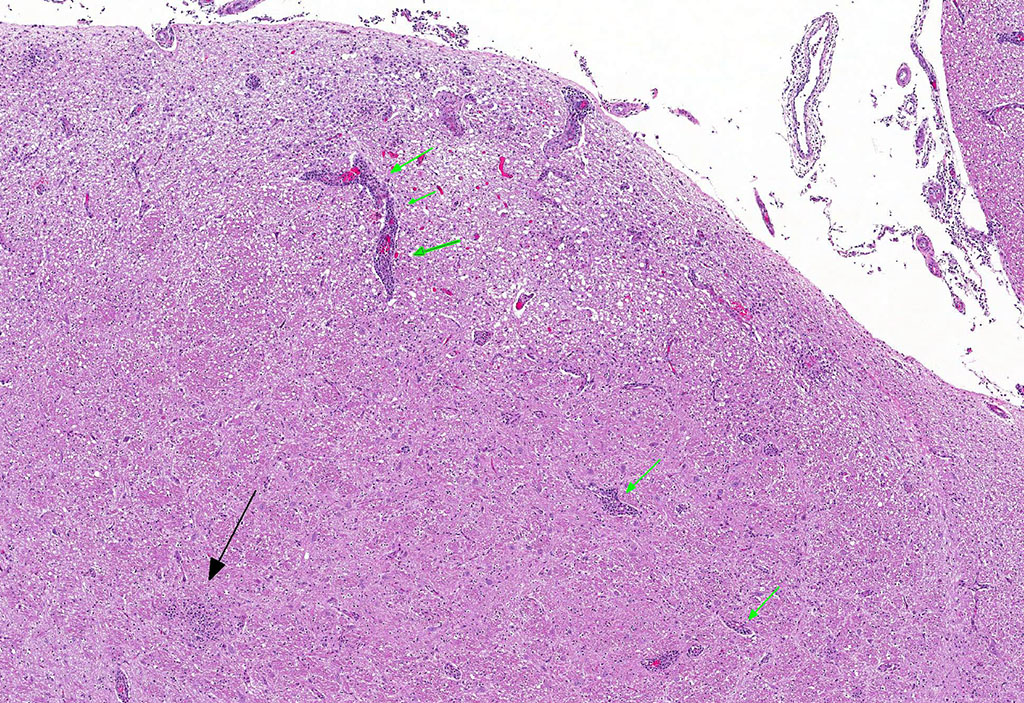

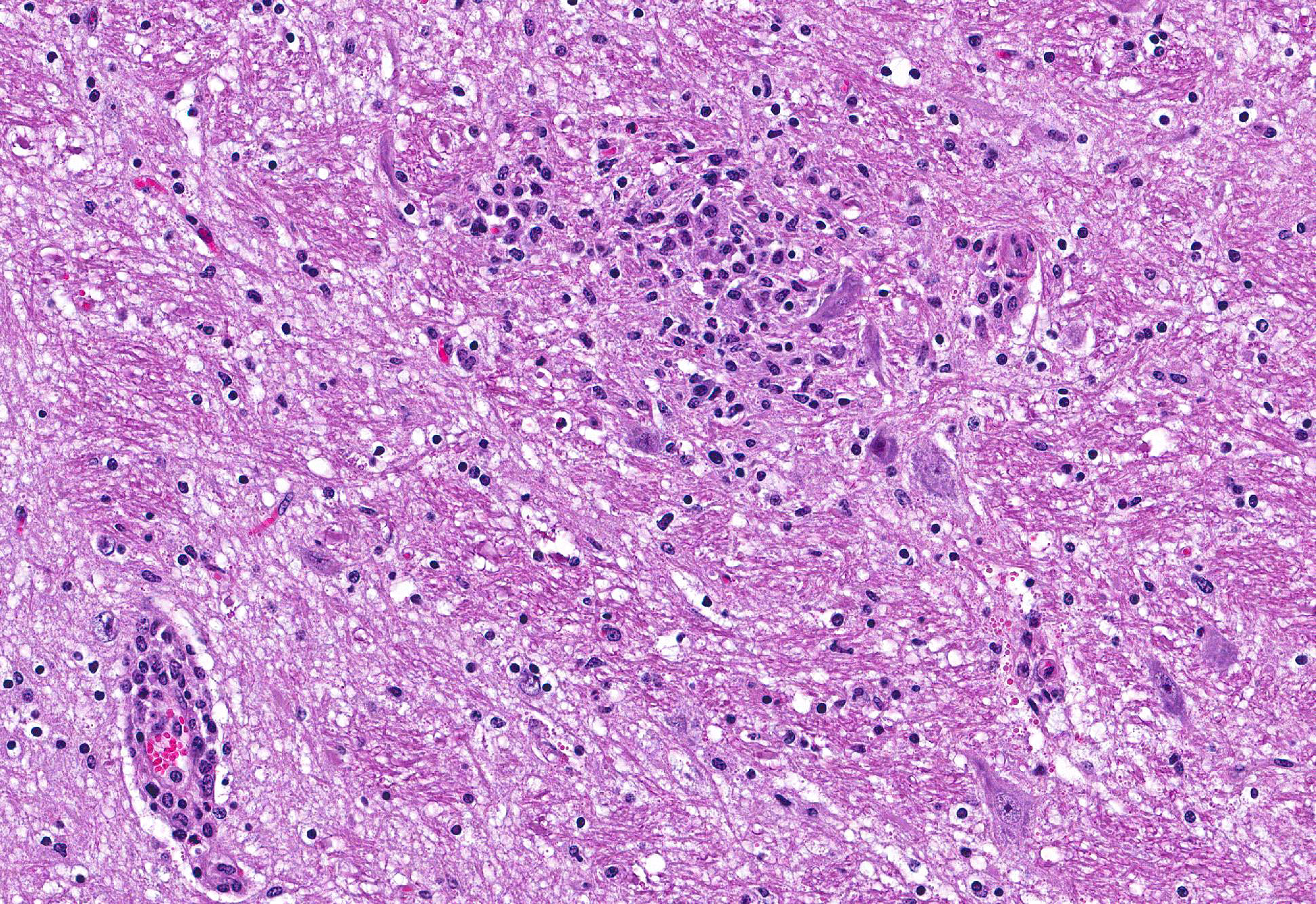

Microscopic Description: Brain: Thromboembolic malacia, multifocal, with proliferation of glial cells, vasculitis, perivascular cuffing, axonal degeneration, meningitis; lymphocytic, moderate to severe.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of the brain is positive for elementary bodies (EB) of Chlamydophila; presumptive, Cp. pecorum. Photomicrograph of brain IHC is included (see positive staining of elementary bodies in macrophages and endothelial cells).

Contributors Morphologic Diagnoses:

Brain: Encephalitis, lymphocytic, multifocal with thromboembolic malacia, vasculitis, perivascular cuffing and meningitis; moderate to severe.

Contributors Comment: When this case was submitted about 22 years ago, a presumptive diagnosis of sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis was made based on clinicopathological findings. the attempt to isolate chlamydial agent was negative, perhaps because of medication with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Serum sample from another sick calf in the group with similar clinical signs and lesions was positive by complement fixation test for Chlamydia antibodies. Recently, because of the availability of IHC, the paraffin block of the brain was retrieved from our repository and tested. We detected positive staining elementary bodies of Chlamydophila (new name for Chlamydia) using genus-specific Chlamydia trochomatis (MONOTOPETM) antiserum.9 According to the manufacturer, the antiserum has cross reactivity with C. pneumoniae and C. psittaci.

Intracellular bacteria of the order Chlamydiales were first associated with diseases of cattle (Bos taurus) when McNutt isolated such organisms from feedlot cattle with sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis.6 Menges7 and Wenner10 in 1953 studied the disease further and proved it was due to an agent belonging to the psittacosis-lymphogranuloma group of viruses. There are currently four families, six genera and 13 species within the order Chlamydiales that have valid published names.4 Two species of the genus Chlamydophila cause disease in ruminants: Cp. abortus (formerly Chlamydia psittaci serotype 1) and Cp. pecorum (formerly Chlamydia pecorum).8 Jee et al reported that the prevalence of C. pecorum in calves to be approximately five times as high as that of C. abortus, with the highest detection rate being with vaginal swabs, compared to rectal or nasal swabs.3 The intestinal chlamydial infection may represent the initial event in the pathogenesis of such disease syndrome as polyarthritis, pneumonia, and encephalomyelitis and probably also transplacental infection and abortion.2

Chlamydophila pecorum is a small, obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium that grows in eukaryotic cells. It has many characteristics of a gram-negative bacterium but it differs in that it lacks peptidoglycan. C. pecorum infects certain mammalian hosts like goats, koalas, sheep, swine and cattle. Because C. pecorum grows slowly within the natural host, actual disease syndromes are not as evident until later in the infectious process. C. pecorum is found mostly in mammals like cattle, sheep, goats, koalas and swine. In koalas, it causes urinary tract disease, infertility, and reproductive diseases. In other mammals, it is associated with abortion, conjunctivitis, encephalomyelitis, pneumonia, polyarthritis and enteritis.5

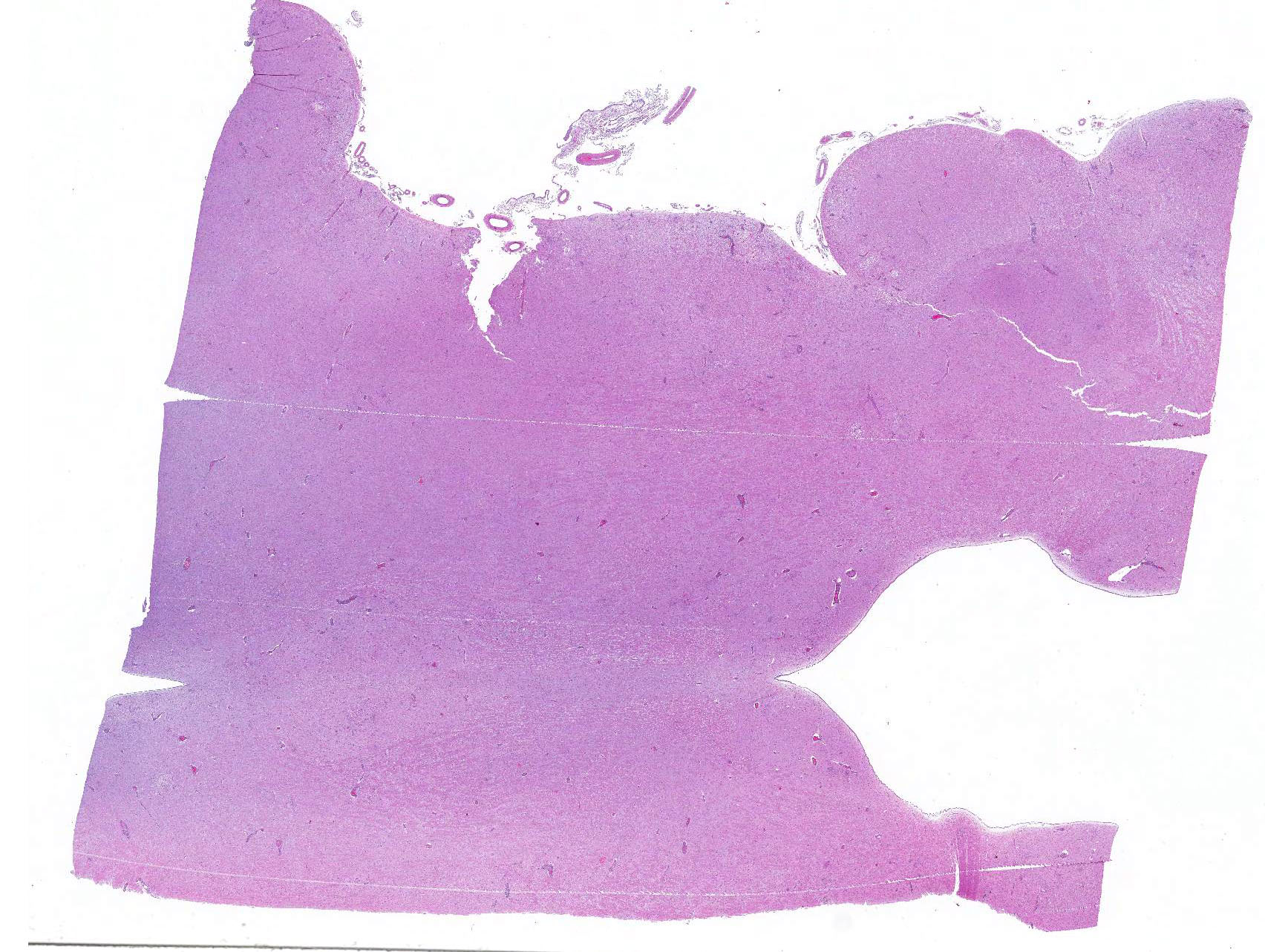

JPC Diagnosis: Brainstem and cerebellum (sections varied): Meningoencephalitis, lymphohistiocytic and neutrophilic, multifocal, moderate with necrotizing vasculitis, Holstein (Bos taurus), bovine.

Conference Comment: Sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis (SBE) is caused primarily by Chlamydophila pecorum (although C. psittaci has also been reported and causes identical disease) which induces severe, diffuse meningoencephalomyelitis in young calves (cattle and buffalo) less than six months old. C. pecorum is an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium that has a tropism for blood vessels, mesenchymal tissue, and serous membranes which explains its range of clinical syndromes: encephalomyelitis, polyarthritis, metritis, conjunctivitis, and pneumonia. Microscopically, vasculitis and polyserositis are hallmark lesions. Grossly, serofibrinous inflammation of serosal membranes (most commonly the peritoneum) and synovia are characteristic.

Gross lesions in the brain are typically sparse with possible fibrin tags and mild congestion of the meninges, which contrasts the remarkable microscopic findings of diffuse meningoencephalomyelitis, particularly severe around the base of the brain. Meningeal inflammation is composed predominately of histiocytes and plasma cells which expand Virchow-Robbins spaces, resulting in marked perivascular cuffing. Prolonged inflammation results in endothelial damage and encephalitis. Small numbers of chlamydiae can be found as elementary bodies within the cytoplasm of mononuclear cells. .1

Microscopic differentials in this case are: Histophilus somni (thrombotic meningoencephalitis), Listeria monocytogenes, and bovine herpesvirus-5.

Histophilus somni, the only member of the genus Histophilus in the family Pasteurellaceae, is a facultative anaerobic gram-negative coccobacillus which is normal flora of the male and female genital tracts and nasal cavity. H. somni initially begins as a septicemic process which may result in acute death, but if the animal lives, it can spread throughout the body causing widespread petechiation and necrosis. Images and literature often focus on the cerebral lesions because they are the most intense; however, microscopically, the hallmark of this disease is vasculitis with secondary thrombosis. Grossly, there is multifocal hemorrhage and necrosis throughout the brain and spinal cord.The pathogenesis is largely unknown, but there are several known important virulence factors: lipo-oligosaccharide (LOS), immunoglobulin Fc-binding proteins, inhibition of oxygen radicals, and intracellular survival. There are two proposed mechanisms of the vasculitis characteristic of this disease: (1) LOS induces activation of caspase-3 and subsequent apoptosis of endothelial cells and (2) LOS activates host platelets which initiate endothelial cell apoptosis by direct activation of caspase-8 and 9. Apoptosis is further boosted by endothelial cell cytokine production, adhesion molecule expression, and production of reactive oxygen species. Additional lesions include: synovitis with petechiae (atlanto-occipital common), pneumonia (when associated with the bovine respiratory complex), ulcerative laryngitis, , retinal hemorrhages, abscesses in the papillary muscles of the left ventricular free wall of the heart, and, less often, otitis externa/media, mastitis, and abortion.1

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that is ubiquitous and able to withstand extreme environmental conditions. L. monocytogenes is an intracellular bacteria that lives in macrophages, neutrophils, and epithelial cells, and has several important virulence factors: internalin (allows it to overcome intestinal, placental, and blood-brain barriers by internalizing with E-cadherin) and cholesterol-binding hemolysin (lysing phagosomes). Subsequently, the bacterium replicates in the cytoplasm of the host cell, and uniquely utilizes host cell actin to transfer from one cell to another. There are three distinct syndromes associated with listeriosis: (1) abortion from infection of the pregnant uterus, (2) septicemia and (miliary????) visceral abscesses, and (3) encephalitis. The septicemic form occurs in neonates and aborted fetuses due to multisystemic bacterial colonization. The encephalitic form occurs in the form of outbreaks of adult animals that have eaten partially fermented silage with a pH of 5.5 or above. The bacteriaenter through wounds in the mucosa (from rough feed) and travels via axons to the trigeminal nerve to the brain, with an unusual affinity for the brainstem. Gross lesions are rarely observed; however, microscopically, there are numerous microabscesses composed of viable and degenerate neutrophils, glial nodules, and marked lymphohistiocytic perivascular cuffing.1

Finally, bovine herpesvirus-5 (BoHV-5), the causative agent of bovine necrotizing meningoencephalitis, occurs as a sporadic disease in young calves. Bovine herpesvirus-5 is antigenically related to bovine herpesvirus-1 (the causative agent of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis), an alphaherpesvirus; both share a tropism for nervous tissue, are latent in the trigeminal ganglion, and exhibit viral recrudescence. Once the organism is introduced nasally or reactivated, it travels via olfactory nerves to the grey matter of the rostral cerebrum (including the olfactory bulb) where it causes severe necrotizing nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis, with marked gliosis. Gross lesions are rare; however, microscopically there is marked lymphoplasmacytic perivascular cuffs, typically more than 6 cell layers thick. There is neuronal necrosis with occasional intranuclear viral inclusions within neurons and astrocytes.1

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory

School of Veterinary Medicine

University of California, Davis

105 W. Central Ave.

San Bernardino, CA 92408

References:

1. Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:362-365, 381, 391-392.

2. Doughri AM, Yong S, Storz J. Pathologic changes in intestinal chlamydial infection of newborn calves. Am J Vet Res. 1974; 35(7):939-944.

3. Greub G. (2010). International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes Subcommittee on the Taxonomy of the Chlamydiae: minutes of the inaugural closed meeting, 21 March 2009, Little Rock, Arkansas, United States of America. Int. J. Syst. Evolut. Microbiol., 60, 26912693. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.0282250.

4. Jee JB, Degraves FJ, Kim TY, and Kaltenboeck B. High prevalence of natural Chlamydophila species infection in calves. J Clin Microbiol. 2004; 42(12): 56645672.

5. Mohamad KY, Rodolakis A. Recent advances in the understanding of Chlamydophila

6. pecorum infections, sixteen years after it was named as the fourth species of the Chlamydiaceae family. Vet. Res. 2010; 41:27.

7. McNutt SH, and Waller EF. Sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis. Cornell Vet. 1940; 30:437-448.

8. Menges RW, Harshfield GS, Wenner HA. Sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis. Studies on pathogenesis and etiology of the disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1953; 122 (913): 294-299.

9. Osman KM, , Ali HA, ElJakee JA, & Galal HM. Infección de cabras y ovejas por Chlamydophila psittaci y Chlamydophila pecorum en Egipto. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 2011; 30 (3): 939-948.

10. ViroStat. Immunochemical for Infectious Disease Research. http://www.virostat-inc.com/

11. Wenner HA, Harshfield GG, Chang TW, and Menges RW. Sporadic bovine encephalomyelitis II. Studies on the etiology of the disease. Isolation of nine strains of an infectious agent from naturally infected cattle. Amer. J. Hyg. 1953; 57: 15-29.