WSC 2023-2024, Conference 24, Case 4

Signalment:

Adult female koala (Phascolarctos cinereus).

History:

A free-ranging koala was found in poor body condition, surrendered to a wildlife hospital, and euthanised on welfare grounds.

Gross Pathology:

Consolidation of the left caudal lung lobe with pleural adhesions.

Laboratory Results:

Heavy growth of anaerobic bacteria from the left caudal lung lobe. Cultured bacteria were identified by bacterial 16S rRNA gene as a novel Actinomyces spp.

Microscopic Description:

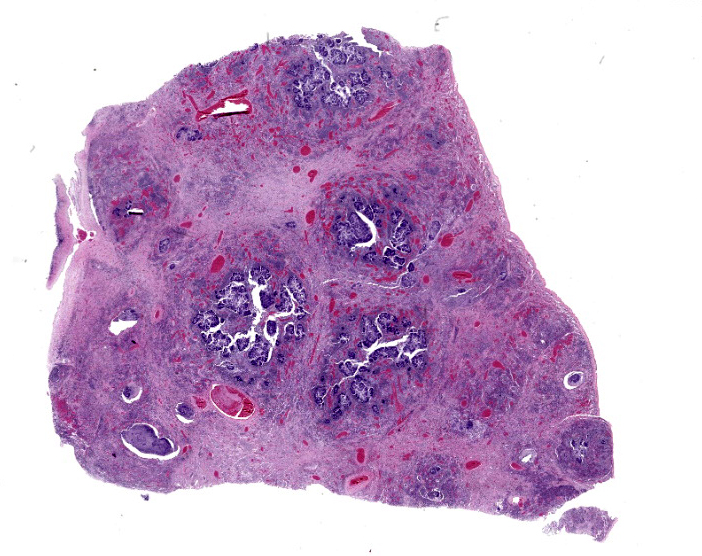

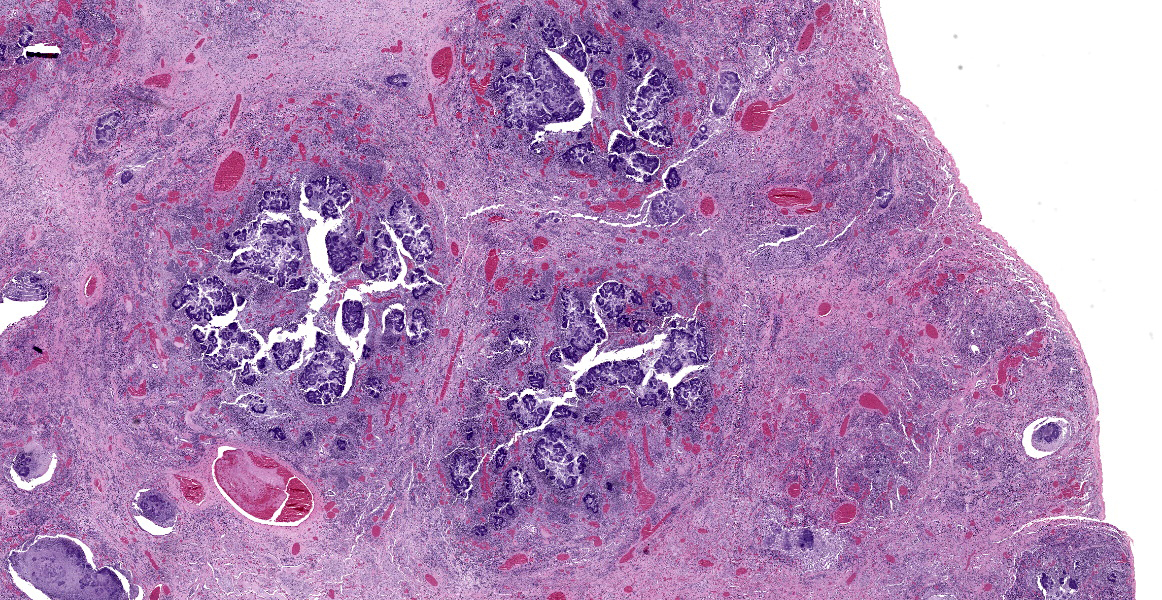

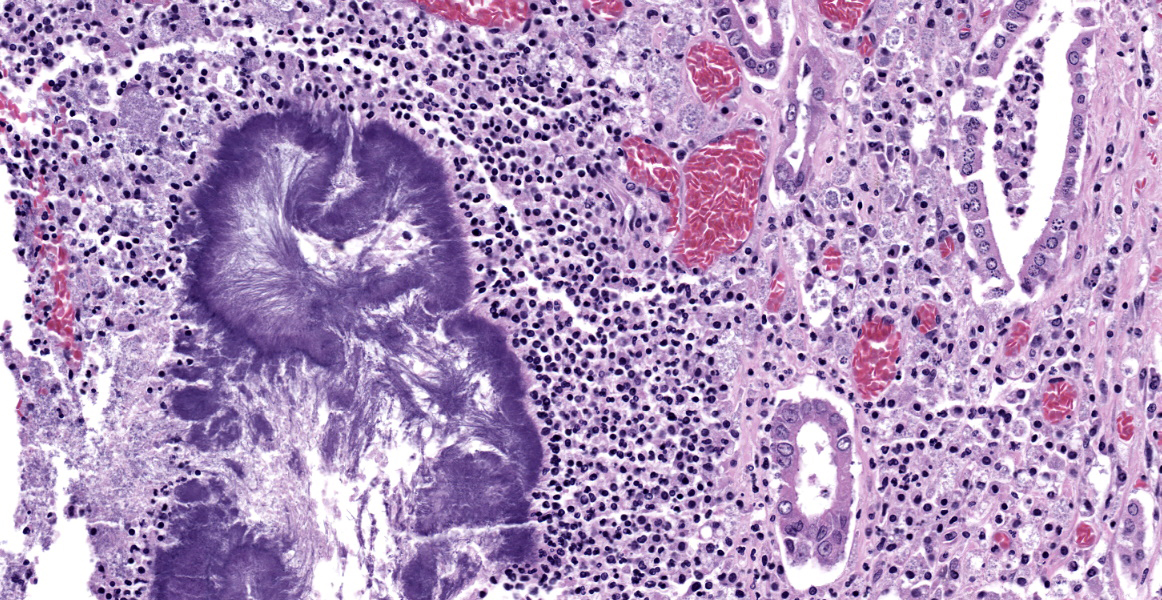

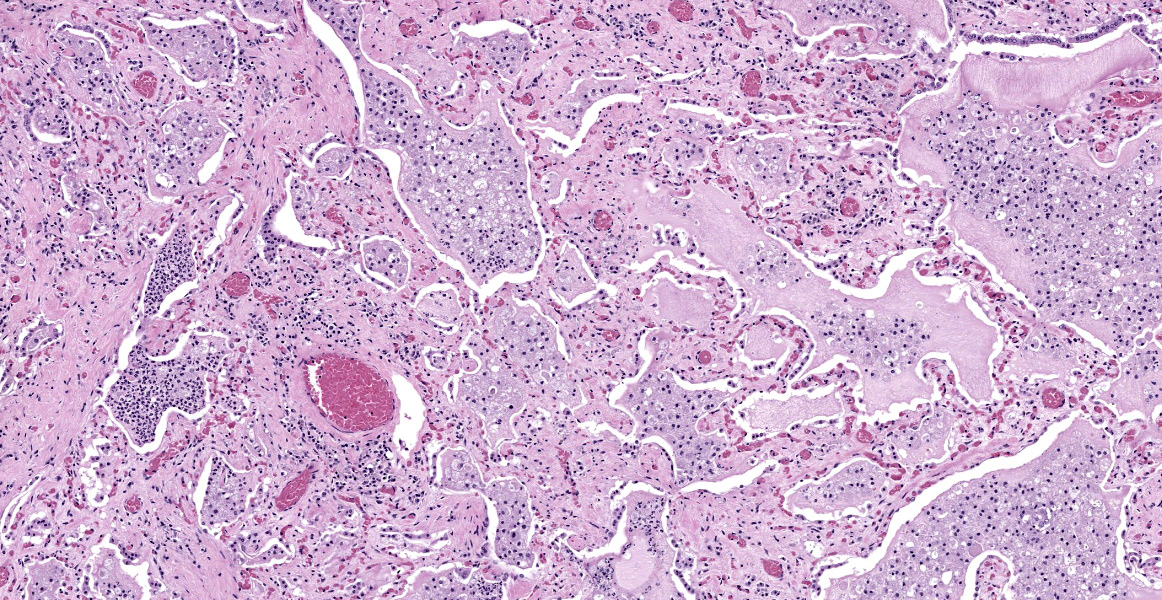

Lung: The normal lung parenchyma is effaced and replaced by branching coarse fibrocollagenous connective tissue (fibrosis), which dissects between multifocal to coalescing densely cellular infiltrates of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Inflammatory infiltrates often cluster around lakes of amorphous necrotic debris and intensely eosinophilic radiating material which surround or are admixed with fine filamentous bacteria (pyogranulomas with central club colonies and Splendore-Hoeppli material). There is moderate to marked irregular expansion of the pleura by immature granulation tissue, haemorrhage, fibrin, and leukocytes.

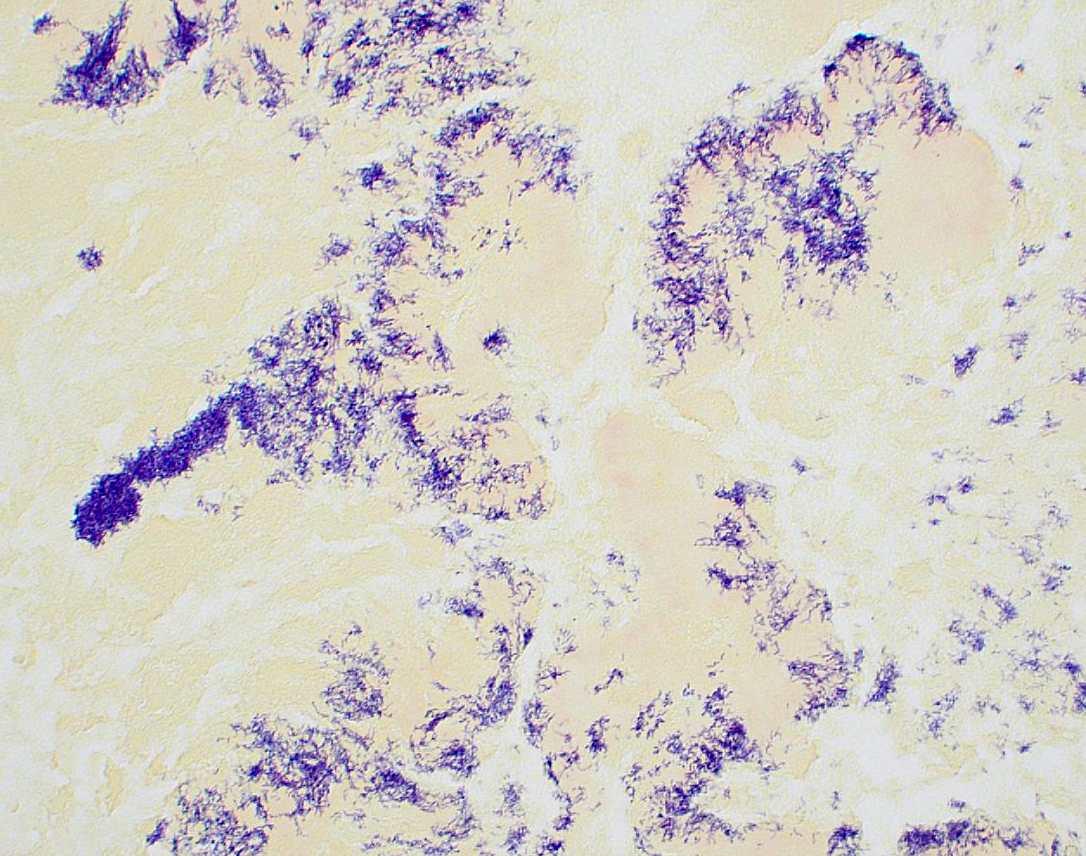

Bacteria are gram-positive, Ziehl-Neelsen and modified Ziehl-Neelsen negative. No organisms are visualized with PAS or Alcian blue stains.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Severe chronic fibrosing pyogranulomatous pleuropneumonia with intralesional filamentous bacteria and Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon.

Contributor’s Comment:

In recent years, free-ranging and captive koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) from the Mount Lofty Ranges of South Australia have been identified with chronic pyogranulomatous bronchopneumonia or lobar pneumonia, most frequently involving the left caudal lung lobe.17 Within lesions, numerous gram-positive or gram-variable, non-acid-fast filamentous bacteria are observed in association with Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. Culture in this case yielded growth of anaerobic bacteria, subsequently identified by molecular techniques as a novel Actinomyces species (pulmonary actinomycosis).

Actinomyces is an anaerobic or facultative aerobic, gram-positive, filamentous bacteria, which is non-spore forming and non-motile.14 Actinomyces species can be found in the normal healthy microbiota of the human oropharynx and gastrointestinal tract and on nasal, oral, or oropharyngeal mucosal surfaces of other animals and are most often associated with opportunistic infections.4,14,18,20 Pulmonary actinomycosis is rare in animals but has been described in a small number of free-ranging species including two chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra),15 a black-tufted marmoset (Cal-lithrix penicillata),16 and in a captive red kangaroo (Osphranter rufus).8

Actinomyces spp. have been reported as commensals of the oral microbiome and associated with similar pulmonary lesions in other species. Examination of resin lung casts from healthy koalas suggests greater laminar flow of air to the left caudal lung lobe in koalas.

Considering the predilection for involvement of the left caudal lung lobe observed in multiple in koalas with this condition, aspiration is suggested as the likely cause in at least some cases of pulmonary actinomycosis in koalas.

Other pathogens reported to cause pneumonia in koalas include Bordetella bronchiseptica,3,11 Chlamydia spp.,1,5,9 Cryptococcus gattii (previously Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii),3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa,2,13 Nocardia asteroides,19 Staphylococcus epidermidis,19 Mycobacterium ulcerans,12 and parasitic pneumonia associated with Marsupiostrongylus sp.10

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences University of Adelaide

Roseworthy, South Australia

https://sciences.adelaide.edu.au/animal-veterinary-sciences/

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Bronchopneumonia, pyogranulomatous, chronic, diffuse, severe, with colonies of filamentous bacilli and Splendore-Hoeppli material.

JPC Comment:

This stunning histologic slide is a remarkable example of bacterial pneumonia caused by Actinomyces, one of the members (along with Yersinia, Actinobacillus, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus spp.) of the “YAACSS” large colony forming bacteria. As the contributor nicely describes, pulmonary actinomycosis is an increasingly recognized disease of koalas, and the history and gross and histologic findings described in this case are characteristic.

The contributor provides an excellent summary here; a more fulsome discussion is provided in the published case series from which this case was taken.17 Pulmonary actinomycosis in koalas affects the left caudal lung lobe in 82% of cases, and is the only affected lobe in 21% of cases.17 In 43% of cases, both the left caudal and the right middle lung lobes are affected.17 Resin cast studies provided a possible answer for this apparent site predilection as the left primary bronchus in the koala follows a relatively straight caudal path without branching into lobar bronchi until deep in the pulmonary parenchyma. In contrast, the right primary bronchus is less linear, branches from the trachea in a more lateral direction, and branches into lobar bronchi much earlier than the left primary bronchus.17 Researchers speculate that the more linear bifurcation pattern creates greater laminar flow, essentially creating a more direct path for bacterial colonization of the left caudal lobe.17

Microbial culture and isolation were performed on five koalas from this case series and a variety of anaerobic agents were identified. PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene matched most closely with Actinomyces timonensis, though due to only 95% sequence homology with the reference A. timonensis genome, researchers speculate that the etiologic agent could be a novel Actinomyces species.17

Pulmonary actinomycosis in South Australian koalas is occasionally accompanied by hypertrophic osteopathy.6 In a recent case study describing this combination of lesions, imaging findings included periosteal reaction on multiple appendicular skeletal bones, including the scapula, humerus, ulna, radius, femur, tibia, fibula, and carpal bones. Gross findings included thick, roughened periosteum on the metaphyses and diaphysis of long bones, and histologic findings included proliferative trabecular bony spicules oriented perpendicular to the cortical bone.6

The moderator began discussion of this case by noting that tissue identification is difficult since the pulmonary architecture is almost entirely obliterated by the florid pyogranulomatous inflammation. The moderator noted that there are many clues to pathogen identity here, including the filamentous morphology of the bacteria, the pyogranulomatous nature of the inflammatory reaction, and the presence of Splendore-Hoeppli material.

As discussed in the previous case of Austwickia chelonae dermatitis, the most commonly encountered filamentous bacteria are Actinomyces, Nocardia, Dermatophilus, and Streptobacillus. The moderator also noted a variety of conditions that are typically associated with Splendore-Hoeppli reaction, including fungal infections (sporotrichosis, zygomycosis, candidiasis, aspergillosis, blastomycosis, orbital pythiosis, pityrosporum folliculitis), bacterial infections (botryomycosis, nocardiosis, and actinomycosis), and parasitic infections (strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis, and cutaneous larval migrans). The intersection of these two differential lists raises a clinical suspicion of actinomycosis even before the inevitable google reveals the susceptibility of koalas to pulmonary actinomycosis. Nevertheless, the moderator noted that Chlamydia spp. is an important rule-out in this case, and participants reviewed a Giemsa stained section that was convincingly negative. Participants were amazed at the florid koality of the inflammation in this case which, even for a koala, is pretty severe, causing participants to spectulate that the koala might be immunosuppressed.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis was straight-forward, with a short aside dedicated to whether the process could be described as necrotizing. In this case, the necrosis is due to inflammatory by-stander damage and not to virulence factors deployed by Actinomyces, so participants preferred a morphologic diagnosis of pyogranulomatous bronchopneumonia.

References:

- Blanshard WH, Bodley K: Chapter 8: Koalas. In: Vogelnest L, Woods, R, eds. Medicine of Australian Mammals. CSIRO Publishing; 2008.

- Canfield PJ. A mortality survey of free range koalas from the north coast of New South Wales. Aust Vet J. 1987:64(11): 325-328.

- Canfield PJ, Oxenford CJ, Lomas GR, Dickens RK. A disease outbreak involving pneumonia in captive koalas. Aust Vet J. 1986:63(9):312-313.

- Couto SS, Dickinson PJ, Jang S, Munson L. Pyogranulomatous meningoenceph-alitis due to Actinomyces sp. in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:650-652.

- Gonzalez-Astudillo V, Allavena R, McKinnon A, Larkin R, Henning J. Decline causes of koalas in South East Queensland, Australia: a 17-year retro-spective study of mortality and morbidity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42587.

- Griffith JE, Stephenson T, McLelland DJ, Woolford L. Hypertrophic osteopathy in South Australian koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) with concurrent pulmonary actinomycosis. Aus Vet J. 2021;99(5):172-177.

- Krockenberger MB, Canfield PJ, Malik R. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus): a review of 43 cases of cryptococcosis. Med Mycol. 2003;41(3):225-234.

- Kunze PE, Sanchez CR, Pich A, Aronson S, Dennison S. Pulmonary actinomycosis and hypertrophic osteopathy in a red kangaroo (Macropus rufus). Vet. Rec Case Rep. 2018;6:e000666.

- Mackie JT, Gillett AK, Palmieri C, Feng T, Higgins DP. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia pecorum in a Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). J Comp Pathol. 2016;155(4):356-360.

- McColl KA, Spratt DM. Parasitic pneumonia in a koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) from Victoria, Australia. J Wildl Dis. 1982;18(4):511-512.

- McKenzie RA, Wood AD, Blackall PJ. Pneumonia associated with Bordetella bronchiseptica in captive koalas. Aust Vet J. 1979;55(9):427-430.

- McOrist S, Jerrett IV, Anderson M, Hayman J. Cutaneous and respiratory tract infection with Mycobacterium ulcerans in two koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). J Wildl Dis. 1985;21(2):171-173.

- Oxenford CJ, Canfield PJ, Dickens RK. Cholecystitis and bronchopneumonia associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a koala. Aust Vet J. 1986;63(10):338-339.

- Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Leonard FC, FitzPatrick ES, Fanning S, Hartigan PJ. Chapter 16: Actinobacteria. In: Quinn PJ, Markey, B.K., Leonard, F.C., FitzPatrick, E.S., Fanning, S., Hartigan, P.J., ed. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. 2 ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2011.

- Radaelli E, Andreoli E, Mattiello S, Scanziani E. Pulmonary actinomycosis in two chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra). Eur J Wildl Res. 2007;53(3):231-234.

- Sousa DER, Wilson TM, Machado M, et al. Pulmonary actinomycosis in a free-living black-tufted marmoset (Callithrix penicillata). Primates 2019;60(2):119-123.

- Stephenson T, Lee K, Griffith JE, et al. Pulmonary actinomycosis in South Australian koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Vet Pathol. 2021;58(2):416-422.

- Valour F, Senechal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197.

- Wigney DI, Gee DR, Canfield PJ. Pyogranulomatous pneumonias due to Nocardia asteroides and Staphylococcus epidermidis in two koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). J Wildl Dis. 1989;25(4):592-596.

- Zhang M, Zhang XY, Chen YB. Primary pulmonary actinomycosis: a retrospective analysis of 145 cases in mainland China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(7):825-831.