Signalment:

Gross Description:

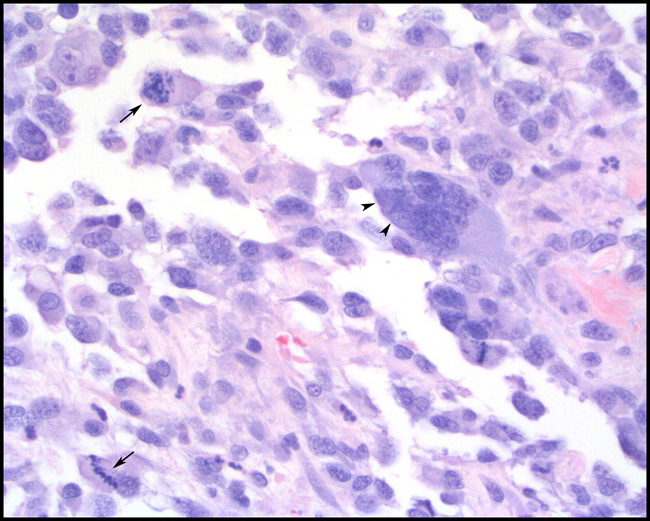

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Mesotheliomas in calves and other neonates are suspected to be due to spontaneous developmental disturbances.9 Dog and human mesotheliomas linked to mineral fibers such as asbestos and erionite exposure may be due to physical irritation of mesothelium, disruption of the mitotic process leading to chromosome damage, increased reactive oxygen intermediate generation and/or persistent kinase-mediated signaling.9,14 Mesotheliomas are also reported to be linked to exogenous hormones, metals and hydrocarbons as well as viruses (including SV40 virus).6

Mesotheliomas have three histological presentations with epitheloid, sarcomatous and biphasic forms. Epitheloid forms often have papillary structures lined by cuboidal basophilic mesothelial cells while sarcomatous forms have spindle cells and large anisocytotic cells with abundant eosinophlic cytoplasm and distinct cell margins.5 Biphasic forms have characteristics of both.

Differential diagnosis include serous carcinomas and normal activated / reactive mesothelium. Differentiation of these three entities can be challenging. Reactive mesothelium usually is not invasive and has less cytologic atypia while carcinomas form acinar structures.8 Immunohistochemistry is useful in differentiating mesotheliomas from carcinomas. Mesotheliomas often stain positive for vimentin, cytokeratin2, LP 34 and also stain for tumor glycoprotein BER EP4, S-100 and HMB 45.1 They stain negatively for carcinoembryonic antigen, CD15 (LEU M1).1 Electron microscopy of mesotheliomas often reveals long, slender, branching and undulate microvilli on apical surfaces while serous carcinomas have fewer, variably lengthed straight microvilli.11

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Cytologic diagnosis of mesotheliomas is difficult as neoplastic mesothelial cells are similar in appearance to reactive mesothelial cells in non-neoplastic effusions.8 Immunohistochemistry can be useful in distinguishing mesotheliomas from other epithelial or non-epithelial neoplasms, although in some instances electron microscopy (EM) is necessary. Characteristic EM features of mesothelial cells include long slender, branching and undulating microvilli on all cell surfaces and prominent desmosomes.1,11 The cytoplasm contains numerous bundles of tonofilaments that are arranged circumferentially around the nucleus.8

F344 rats are predisposed to mesotheliomas in the tunica vaginalis of the testes with occasional subsequent implantation on the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum.1,10,12

Other neoplasms that have positive immunoreactivity for both cytokeratin and vimentin include meningioma 8, chordoma8, clear cell adnexal carcinoma16, ciliary body adenoma/adenocarcinoma7, anaplastic carcinoma8, synovial cell sarcoma (biphasic)8, and carcinosarcoma.15

References:

2. Barker IK: The peritoneum and retroperitoneum. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals. eds. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, pp. 234. Academic Press Inc., San Diego, CA, 1993

3. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK: Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 294. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

4. Caswell JL, Williams KJ: Respiratory system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 578. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

5. Geninet C, Bernex F, Rakotovao F, Crespeau FL, Parodi AL, Fontaine JJ: Sclerosing peritoneal mesothelioma in a dog a case report. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 50: 402-405, 2003

6. Ilgren EB, Browne K: Background incidence of mesothelioma: animal and human evidence. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 13:133-149,1991

7. Lieb WE, Shields JA, Eagle RC Jr, Kwa D, Shields CL: Cystic adenoma of the pigmented ciliary epithelium. Clinical, pathologic, and immunohistopathologic findings. Ophthalmol 97:1489-1493, 1990

8. Meuten DJ: Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th ed., pp. 227-233, 477-478, 594, 721, 729. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2002

9. Misdorp WP: Tumours in calves: Comparative aspects. J Comp Pathol 127:96-105, 2002

10. Mitsumori K, Elwell MR: Proliferative lesions in the male reproductive system of F344 rats and B6C3F1 mice: incidence and classification. Environ Health Perspect 77:11-21, 1988

11. Ordonez NG: The diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in distinguishing between peritoneal mesotheliomas and serous carcinomas: A comparative study. Mod Pathol 19:34-48, 2006

12. Percy DH, Barthold SW: Rat. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 3rd ed., pp. 174-176. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2007

13. Robinson BW, Musk AW, Lake RA: Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet 366:397-408, 2005

14. S+�-�nchez J, Buend+�-�a AJ, Vilafranca M, Velarde R, Altimara J, Mart+�-�nez CM, Navarro JA: Canine carcinosarcomas in the head. Vet Pathol 42:828-833, 2005

15. Schulman FY, Lipscomb TP, Atkin TJ: Canine cutaneous clear cell adnexal carcinoma: histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and biologic behavior of 26 cases. J Vet Diagn Invest 17:403-411, 2005

16. Wilson DW, Dungworth DL: Tumors of the respiratory tract. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp. 398. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2002

17. Wilson TM, Brigman G: Abdominal mesothelioma in an aged guinea pig. Lab Anim Sci 32:175-176, 1982