WSC 2022-2023

Conference 12

Case III

Signalment:

3-month-old castrated male Angus Cross (Bos taurus) bovine.

History:

6 out of 30 calves showed acute clinical signs including: bruxism, rapid breathing, dehydration, difficulty rising, and difficulty passing manure. All animals were normothermic (99.5-99.9 F). The herd was pastured in a native grass meadow with oak trees. The area recently received 3 feet of snow, during which the herd sheltered under the oak trees. The submitted animal died shortly after being tubed with fluids. The referring veterinarian submitted kidney, liver and ruminal contents to the diagnostic laboratory for evaluation

Laboratory Results:

Gallic acid was strongly positive in the submitted rumen contents, confirming exposure to gallotannins.

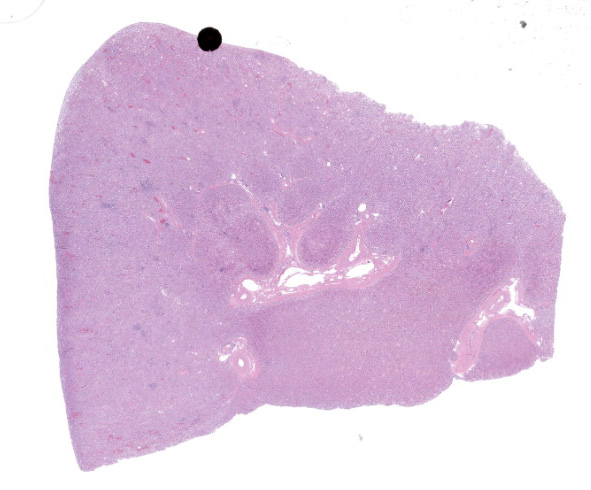

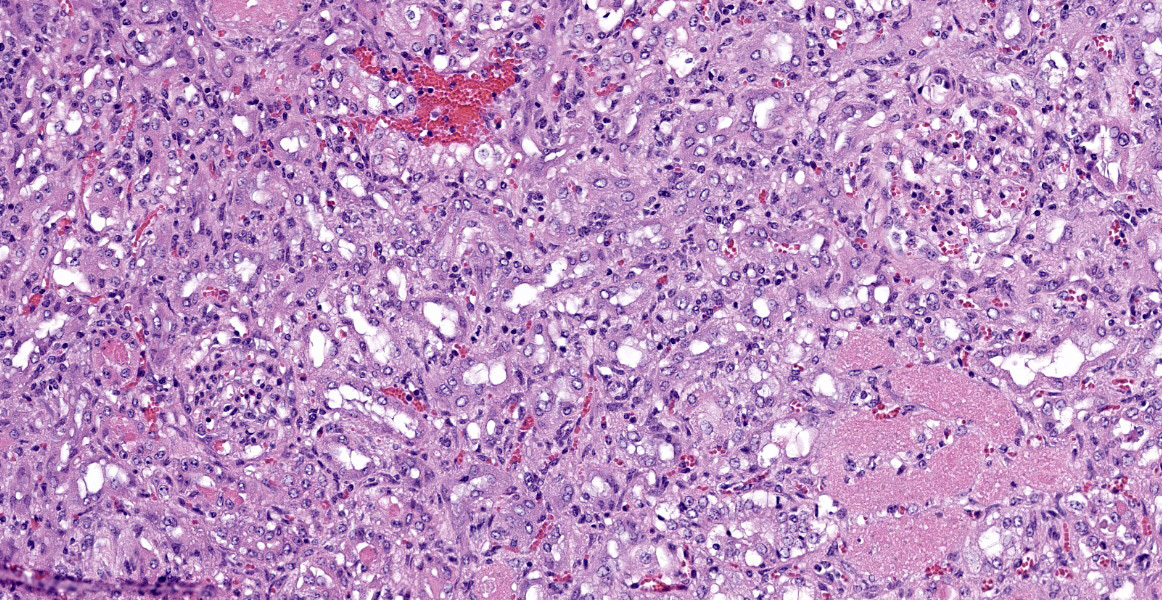

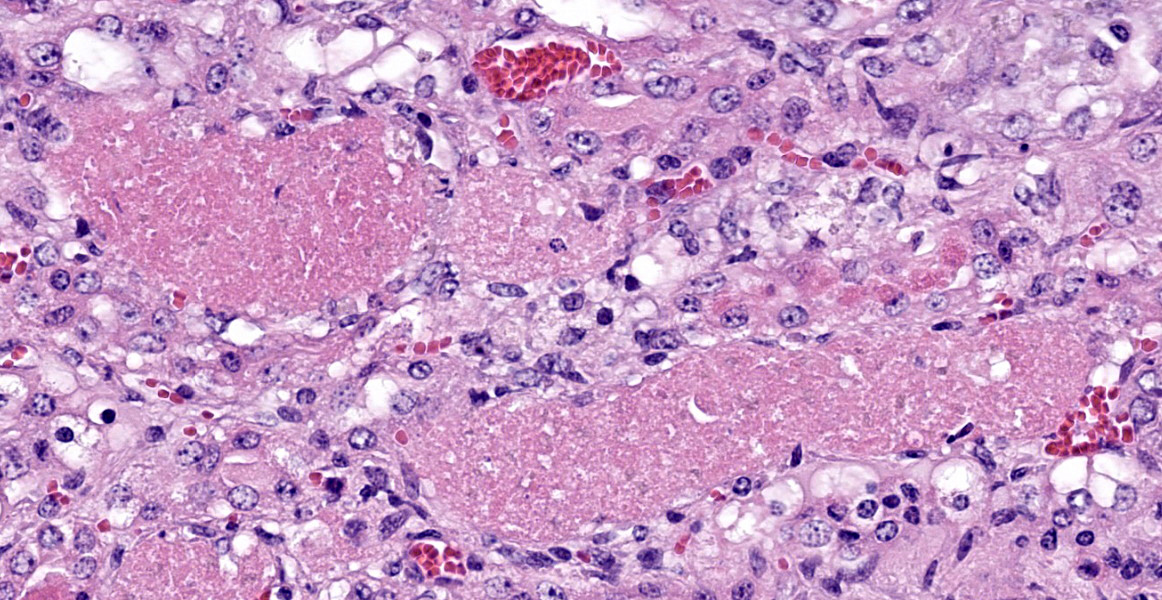

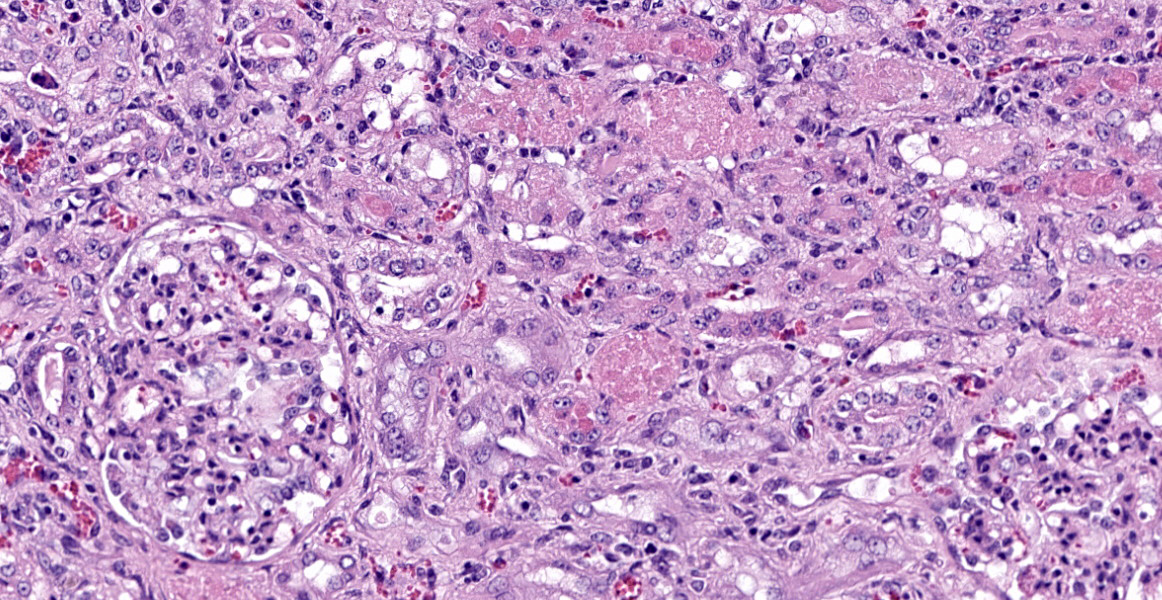

Microscopic Description:

Kidney: Approximately 30% of the cortical tubular epithelium is necrotic, characterized by loss of cellular detail, rounding of cell borders, separation from the basement membrane, pyknotic nuclei and cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia. Affected tubules are often expanded by brightly eosinophilic granular casts composed of cellular debris and mild amounts of hemorrhage. Occasionally the

tubular epithelium is attenuated, mildly vacuolated (degeneration), or hypertrophied with moderate anisokaryosis and rare mitotic figures (regeneration). Few Bowman’s spaces and tubules contain high protein fluid. Multifocally the interstitium is expanded by mild fibrosis with infiltration by small aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells with fewer neutrophils. The tunica media of large and medium-caliber vessels are mildly vacuolated.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Kidney: Moderate acute/subacute multifocal cortical tubular necrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

The history, histologic lesion, and presence of gallic acid in the rumen are diagnostic for oak toxicosis. Multiple species are potentially susceptible to oak toxicosis including: cattle, sheep, goats, llamas, moose, rabbits, horses, and pigeons.4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 17, 19 Suspected oak toxicosis has been reported in one dog.3 Tannins leached from oak leaves that fall into aquatic habitats are known to be toxic to some tadpole species.10 Pigs appear to be resistant as ingestion increases production of tannin-binding salivary proteins.17

Cattle are the most susceptible and most commonly reported species. Cattle develop acute tubular necrosis after ingestion of blossoms, buds, leaves, stems or acorns from oak shrubs and trees (Quercus spp) which grow worldwide with case reports in North America, Brazil, Spain, Israel and Africa.6, 14, 15, 18, 20 Consumption of large quantities of young oak leaves typically occurs in the spring and ingestion of bark or green acorns occurs in the fall. Toxic levels vary between plant species, plant component, and stage of plant maturity.1 The toxicity of the leaf decreases with maturity, while the opposite occurs with the acorns which are most toxic when mature and freshly fallen.16 Cattle frequently forage oak components without issue if the oak products represent less than 50% of their diet, therefore feed restriction plays a crucial role, as in this case with snow coverage removing availability of the herd’s regular pasture diet.8 Oak is also not considered to be generally palatable, reinforcing the importance of other feed availability to avoid toxicosis. The toxic substances are metabolites of tannins which are believed to include: tannic acid, gallic acid and pyrogallol.2,5 Toxicosis is dose-dependent and the exact mechanism of renal tubular damage is unknown. The binding of tannins to endothelial cells results in widespread endothelial damage and can lead to perirenal edema, hydrothorax, ascites and disseminated intravascular coagulation.5

Clinical signs occur 3-7 days after ingestion and mortality can be as high as 80%.20 Clinical signs related to endothelial damage and renal failure are typical and can include: polyuria, polydipsia, hematuria, dehydration and sternal edema. Animals may also experience abdominal pain, mucoid to hemorrhagic diarrhea, tenesmus, icterus, rumen stasis, anorexia and depression. Malformed calves and abortions have been reported in cows that consume acorns during the second trimester of pregnancy.11 Clinical pathology findings may include increased BUN and creatinine concentrations, proteinuria, glucosuria, hyperbilirubinuria, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hyposthenuria. Other findings reported include elevated AST, GGT, CK, and lactate dehydrogenase, hypoalbuminemia, hypocalcemia and hypoproteinemia.2, 5, 6, 14, 16, 20

Typical gross findings include swollen, pale kidneys with pinpoint hemorrhages on the capsular and cortical surfaces, perirenal edema and hemorrhage, hydrothorax, ascites, and alimentary tract ulceration. Histopathological findings within the kidney are characterized by acute proximal tubular necrosis with casts and intratubular hemorrhage. Chronic cases develop chronic interstitial nephritis with fibrosis, atrophy, thinned cortex and a finely pitted surface. 2, 5, 6, 14, 15, 16, 20

The diagnosis of oak poisoning is typically based on clinical and gross findings, provided history and histopathological examination of the kidneys. Commercial diagnostic testing for tannin metabolites is available for confirmation. Additional differentials for acute tubular necrosis in cattle include: pigweed (Amaranthus spp) toxicity, aminoglycoside antibiotic toxicity, oxalate poisoning, urolithiasis, heavy metal exposure, and ochratoxicosis, yet tubular necrosis with intratubular hemorrhage distinguishes this nephrotoxicity from most other causes.5

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO, USA

http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/vdl/Pages/default.asp

JPC Diagnosis:

Kidney: Tubular degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, diffuse, with intratubular granular casts, hemorrhage, and proteinosis.

JPC Comment:

This is a classic case of oak toxicosis. In addition to exogenous toxins so thoroughly described by the contributor, acute tubular injury (ATI) can also be caused by endogenous toxins.5 Massive release of hemoglobin or myoglobin from hemolysis or rhabdomyolysis can cause pigmentary nephrosis. Tubular injury in these cases may stem from the toxic effects of pigments and secondary factors, such as anemia.5 Bile is also nephrotoxic in domestic animals.5 In humans, hepatic cirrhosis causes systemic hypotension and renal hypoperfusion which lead to tubular injury, and bile pigments build up in tubular epithelium and form bile casts in tubules.5

Acute tubular injury also occurs as part of renal cortical necrosis; in this condition, all cortical structures, including glomeruli, are damaged. Differentials for renal cortical necrosis include hypoperfusion, ischemia, endotoxemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and certain gastrointestinal disease.5 In some cases, distinguishing ATI and renal cortical necrosis may be difficult as edema may decrease perfusion and cause concurrent ischemia.5

The ability to recover from ATI is dependent on preservation of basement membranes.5 Jones periodic methenamine silver staining and other stains can provide valuable prognostic information in biopsy cases.

References:

- Basden KW, Dalvi RR. Determination of total phenolics in acorns from different species of oak trees in conjunction with acorn poisoning in cattle. Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 1987;29.4:305-306.

- Breshears MA, Confer AW. The urinary system. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathological Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier Inc.; 2017: 672-673.

- Camacho F, Stewart S, Tinson E. Successful management of suspected acorn (Quercus petraea) toxicity in a dog. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2021;62.6: 581.

- Chamorro MF, Passler T, Joiner K, et al. Acute renal failure in 2 adult llamas after exposure to Oak trees (Quercus spp.). The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2013; 54.1:61.

- Cianciolo RE, Mohr FC. Urinary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:439-441.

- Cortinovis C, Caloni F. Epidemiology of intoxication of domestic animals by plants in Europe. The Veterinary Journal. 2013;197(2):163-8.

- Díez MT, del Moral PG, Resines JA, et al. Determination of phenolic compounds derived from hydrolysable tannins in biological matrices by RP-HPLC. Journal of separation science. 2008; 31.15:2797-2803.

- Doce RR, Belenguar A, Toral PG, et al. Effect of the administration of young leaves of Quercus pyrenaica on rumen fermentation in relation to oak tannin toxicosis in cattle. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2013;97.1: 48-57.

- Dollahite JW, Pigeon RF, Camp, BJ. The toxicity of gallic acid, pyrogallol, tannic acid, and Quercus havardi in the rabbit. American journal of veterinary research. 1962;23:1264-1267.

- Earl JE, Semlitsch RD. Effects of tannin source and concentration from tree leaves on two species of tadpoles. Environmental toxicology and chemistry. 2015;34.1:120-126.

- James LF, Nielsen DB, Panter KE. Impact of poisonous plant on the livestock industry. Rangeland Ecology & Management/Journal of Range Management Archives. 1992:45.1: 3-8.

- Meiser H, Hagedorn HW, Schulz R. Pyrogallol poisoning of pigeons caused by acorns. Avian diseases. 2000:205-209.

- Meiser H, Hagedorn HW, Schulz R. Pyrogallol concentrations in rumen content, liver and kidney of cows at pasture. Berliner und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift. 2000;113.3:108-111.

- Neser JA, Coetzer JAW, Boomker J, Cable H. Oak (Quercus rubor) poisoning in cattle. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 1982;53.3:151-155.

- Pérez V, Doce RR, García-Pariente C, et al. Oak leaf (Quercus pyrenaica) poisoning in cattle. Research in Veterinary Science. 2011;91.2:269-277.

- Plumlee KH, Johnson B, Galey FD. Comparison of disease in calves dosed orally with oak or commercial tannic acid. Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation. 1998;10.3:263-267.

- Smith S, Naylor RJ, Knowles EJ, et al. Suspected acorn toxicity in nine horses. Equine Veterinary Journal. 2015;47(5):568-572.

- Spier SJ, Smith BP, Seawright AA, Norman BB, Ostrowski S, Oliver MN. Oak toxicosis in cattle in northern California: clinical and pathologic findings. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1987;191.8:958-964.

- Vikøren T, Handeland K, Stuve G, Bratberg B. Toxic nephrosis in moose in Norway. Journal of wildlife diseases. 1999;35(1):130-3.

- Yeruham I, Avidar Y, Perl S, et al. Probable toxicosis in cattle in Israel caused by the oak Quercus calliprinos. Veterinary and human toxicology. 1998;40(6):336-40.