CASE 3: 16-A817 (4118327-00)

Signalment:

Juvenile (2.5-year-old) female Indian-origin rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta)

History:

The animal was a colony assigned animal, born at the ONPRC and outdoor-housed in a social group. She presented for diarrhea and dehydration with 17% weight loss since the last recorded weight five months prior. There were no previous clinical presentations. Fecal cultures were positive for both Campylobacter coli and Shigella flexneri. Abdominal ultrasound revealed thickened stomach and small intestinal walls, gastric distension with hypoechoic ingesta and gas, and small intestinal hypermotility and distension with anechoic liquid digesta. Colonic wall thickness could not be measured; however, prominent layering with gas and liquid feces were noted within the large intestine. The diarrhea continued despite three weeks of antibiotic administration (enrofloxacin and azithromycin) followed by another week of anti-inflammatory therapy (sulfasalazine and prednisone). Due to poor prognosis, euthanasia was elected, and the animal submitted for post-mortem examination.

Gross Pathology:

Chronic negative energy balance (BCS 1.5/5), thickened, corrugated cecal and colonic mucosa with trichuriasis, and renal cortical pallor consistent with acute tubular necrosis.

Laboratory results:

PCR of section of cecum were positive for Mycobacterium avium.

Microscopic description:

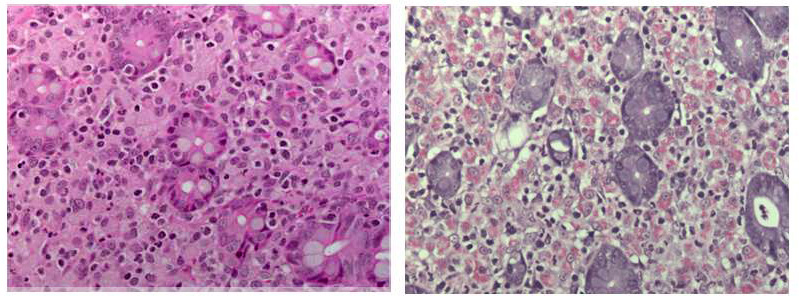

Ileocecal junction: Multifocally within the cecum are large aggregates of histiocytes with intracytoplasmic rod-shaped bacteria that expand the lamina propria, separating and replacing crypts. The mucosa is diffusely thickened, up to 3x normal, with elongated crypts that are lined by epithelial cells with increased basophilia and mitoses (proliferation). The lamina propria is also expanded by increased lymphocytes and plasma cells, along with a moderate infiltrate of neutrophils and mucin-laden macrophages, which often extend into the muscularis mucosa and submucosa. Along the luminal surface is a paucity of normal bacteria (loss of commensal surface bacteria) and luminal mucosa is often attenuated with occasional loss of epithelial cells (erosion). Crypts are frequently dilated, lined by attenuated epithelium, and contain aggregates of degenerate neutrophils and karyorrhectic debris (crypt microabscesses). Hyperplastic gut-associated lymphoid tissue contains expanded germinal centers, along with occasional intact crypts (crypt herniation). There is focal hemorrhage within the cecal submucosa. Within the distal ileum, the villi are segmentally blunted (atrophy) and fused. The lamina propria is multifocally expanded by acellular, homogenous, eosinophilic material (amyloid). The subcapsular spaces and medullary sinus of the ileocolic lymph node contain a moderate infiltrate of foamy macrophages and rare multinucleated giant cells.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

1. Cecum: Typhlitis, granulomatous, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, marked with histiocytic intracytoplasmic acid-fast rod-shaped bacteria

2. Cecum: Typhlitis, proliferative, lymphoplasmacytic, neutrophilic, chronic-active, diffuse, moderate to marked with crypt abscesses and herniation, multifocal mucosal erosion, loss of commensal surface bacteria, and focal submucosal hemorrhage

3. Ileum: Amyloid deposition, proprial, multifocal, mild with villus atrophy and fusion

4. Ileocolic lymph node: Histiocytosis, sinus and subcapsular, multifocal, mild with rare multinucleated giant cells

Contributor's comment:

Several disease processes are present in the section submitted that demonstrate classic enteric diseases of rhesus macaques: mycobacteriosis, chronic proliferative typhlocolitis, and secondary amyloidosis. Acid-fast histochemical stain revealed florid intracytoplasmic organisms within histiocytes of the cecum and colon. Microscopically, there were also small granulomatous nodules in the liver with rare intracytoplasmic acid-fast positive rod-shaped bacteria. PCR of paraffin-embedded sections of cecum confirmed Mycobacterium avium complex (Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare). Congo red histochemical stains highlighted congophilic material that demonstrated apple-green birefringence upon polarized light within the ileum, as well as in the stomach, jejunum, and colon.

Mycobacterium avium complex bacteria are ubiquitous in soil, dust, and aquatic environments, where mammals can be exposed to the organisms and develop subsequent disease.8 Like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mycobacteriosis can cause significant disease in old and new world nonhuman primates and occurs most commonly in macaques that are immune compromised.7 As such, animals with mycobacteriosis are usually indoor-housed, protocol-assigned, and undergoing irradiation therapies or experimental infection with immunosuppression-causing pathogens such as simian immunodeficiency virus. In natural infections, mycobacteriosis is most commonly described in the small intestine, similar to Johne's disease (Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis) in other veterinary species. However, disseminated disease does occur and may affect the colon, liver, and lymph nodes.7 In the present case, the organisms were present in the large intestine and liver, but no small intestinal granulomatous inflammation was noted. Another unusual aspect of the case is that the animal was outdoor-housed with no known disease that could account for a state of immunosuppression.

Proliferative typhlocolitis, or chronic colitis of macaques, is the most common disease causing morbidity and mortality in many nonhuman primate facilities.4 It is characterized by hyperplastic cecal and colonic mucosa with variable proprial infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, crypt abscesses, loss of goblet cells, gut-associated lymphoid hyperplasia, and crypt herniation.4 Other findings include superficial epithelial tags, presence of mitotic figures in the upper half of glands, and lack of filamentous bacteria that normally colonize the luminal surface. This entity occurs in both nursery-raised and group-housed, maternally reared animals. It is primarily seen in young animals between 1 and 3 years of age. Initial episodes of diarrhea may be associated with positive fecal cultures for Campylobacter spp5 or Shigella flexneri, as in this case. Subsequent episodes are characterized by normal enteric flora and the variable presence of protozoa. The pathogenesis is thought to be complex involving repeated enteric infections, malnutrition associated with enteric disease, compromised mucosal defenses, environmental stresses, and possible hypersensitivity to dietary antigens.4 Proliferative typhlocolitis is often seen in conjunction with acute renal tubular degeneration and necrosis, which is due to hypoperfusion caused by diarrhea-induced hypovolemia.

Secondary amyloid deposition in macaques is commonly associated with proliferative typhlocolitis due to the state of chronic inflammation. The other main condition associated with amyloidosis in macaques is chronic arthritis.1 Microscopically, amyloid may be noted in the proprial tissues and around blood vessels of the gastrointestinal tract, interstitium of the renal medulla, spaces of Disse in the liver, cortical-medullary junction of adrenal glands, spleen, and within lymph nodes.1 As in humans and other animals with chronic inflammation, secondary amyloid deposition in macaques is due to misfolded serum amyloid A (SAA) proteins.2 Misfolded proteins undergo limited proteolysis before monomers assemble to form beta-sheets that make up the AA fibrils.2 AA amyloidosis is considered to be species-specific and is typically non-transmissible between species.6 New studies in mice, however, are challenging this concept and have shown limited AA amyloid deposition with transfer of bovine and feline AA amyloid extracts in IL-1 receptor antagonist knock out mice.9 In rhesus macaques, AA amyloid deposition in the intestine may be associated with chronic negative energy balance due to malabsorption, often compounding the clinical signs of chronic diarrhea.1

Contributing Institution:

Oregon National Primate Research Center

Oregon Health & Science University

505 NW 185th Ave.

Beaverton, OR 97006

http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/research/centers-institutes/onprc/

JPC diagnosis:

1. Cecum and colon: Typhlocolitis, lymphohistocytic and proliferative, chronic, diffuse, severe with crypt abscesses and edema.

2. Ileum: Ileitis, lymphohistiocytic, diffuse, moderate with mucosal edema.

3. Ileum, mucosa: Amyloidosis, multifocal to coalescing, moderate.

4. Mesenteric lymph node: Reactive hyperplasia, with medullary histiocytosis.

JPC comment:

The contributor succinctly describes a case of multiple pathologies in this nonhuman primate. While proliferative colitis (or typhlocolitis) has been noted in colonies of macaques, there is potential overlap and causation with the condition Idiopathic Chronic Diarrhea ICD), which has been well characterized in populations at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC). In these cases, there is a lymphoplasmacytic colitis similar to that seen in human disease, including the subet of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (I-IBS). In the population of rhesus macaques analyzed, most had historic Campylobacter spp and/or trichomonad infections, and the ICD animals had positive culture results at much higher rates than the control animals. The ICD animals also had an absence of normal colonic bacteria of epithelium-oriented bacteria and an overgrowth of trichomonads, determined to be Helicobacter macacae and Pentatrichomonas hominis as compared to controls, with most having received antibiotic therapy. ICD animals also have decreased IL-4 expression in the ileum and colon, potentially suggesting either a preexisting condition that prevented development of these CD4+ Th2 cells, or there was a disease induced shift away from this expression pattern. While ICD may be related to the described proliferative typhlocolitis and shares several features, additional research is needed to elucidate the causal relationships between gastrointestinal flora, disease, and any preexisting conditions.3

As the contributor stated, most immunocompetent macaques do not experience significant pathology from Mycobacterium intracellulare. However, there have been reports of intestinal pathology associated with M. intracellulare, which included mild to severe thickening of the intestinal, cecum, or colon wall, thickening of the intestinal mucosa with a granular to corrugated appearance, with prominent lymphatic channels in the mesentery. Typically, the inflammation is of a granulomatous character, with acid-fast bacilli visualized in macrophages with Ziehl-Neelsen stained sections. In this case, it becomes difficult to determine whether 1) an immune suppressing condition caused the susceptibility to M. intracellulare, which resulted in the eventual mucosal changes seen consistent with proliferative typhlocolitis, or 2) the course of chronic typhlocolitis resulted in sufficient immune suppression that the animal experienced pathologic effects from M. intracellulare.7 This animal may have been infected with various immune suppressive viruses as well, such as simian retrovirus (SRV), of which there are several potential strains (SRV-1, SRV-2, SRV-3, SRV-5).7 A more distant possibility remains infections with simian immunodeficiency virus, though there is was no exposure noted, and no histopathology consistence with that disease reported.

References:

- Blanchard JL, Baskin GB, Watson EA. Generalized amyloidosis in rhesus monkeys. Vet Path 1986;23(4):425-430.

- Kumar V. Diseases of the Immune System. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic basis of disease. 9th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015:185-264.

- Laing ST, Merriam D, Shock BC, et al. Idiopathic colitis in Rhesus Macaques is associated with dysbiosis, abundant enterochromaffin cells and altered T-cell cytokine expression. Vet Pathol. 2018;55(5):741-752.

- Lewis AD, Colgin LMA. Pathology of noninfectious diseases of the laboratory primate. In: The Laboratory Primate. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2005:47?74. (Book chapter ? electronic copy unavailable)

- McKenna P, Hoffmann C, Minkah N, et al. The macaque gut microbiome in health, lentiviral infection, and chronic enterocolitis. PLoS Pathog 2008;4(2):e20.

- Scott MR, Peretz D, Nguyen HO, et al. Transmission barriers for bovine, ovine, and human prions in transgenic mice. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5259?5271.

- Simmons J and Gibson S. Chapter 2: Bacterial and mycotic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Nonhuman primates in biomedical research 2nd edition, edited by Abee C, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T. London NW: Academic Press, 2012: 116-117.

- Thorel MF, Huchzermeyer HF, Michel AL. Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in mammals. Rev Sci Tech 2001;20(1):204-18.

- Watanabe K, Uchida K, Chambers JK, et al. Experimental transmission of AA amyloidosis by injecting AA amyloid protein into interleukin-1 receptor antagonist knockout (IL-1raKO) mice. Vet Path 2015;52(3):505-512