CASE II: 174994-20 (JPC 4167688)

Signalment:

2-year-2-month-old, male castrated, Coonhound mix, Canis familiaris, dog.

History:

Over one year history of chronic diarrhea, anemia, and iron deficiency, treated for suspected inflammatory bowel disease with prednisolone. Near the time of biopsy, he developed gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected steroid-induced hepatopathy. The dog was off prednisolone for 2 weeks prior to the biopsy.

Gross Pathology:

The liver was diffusely dark brown to almost black. The small and large intestines were thickened with a mottled pink-white serosal surface. The mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory Results:

None.

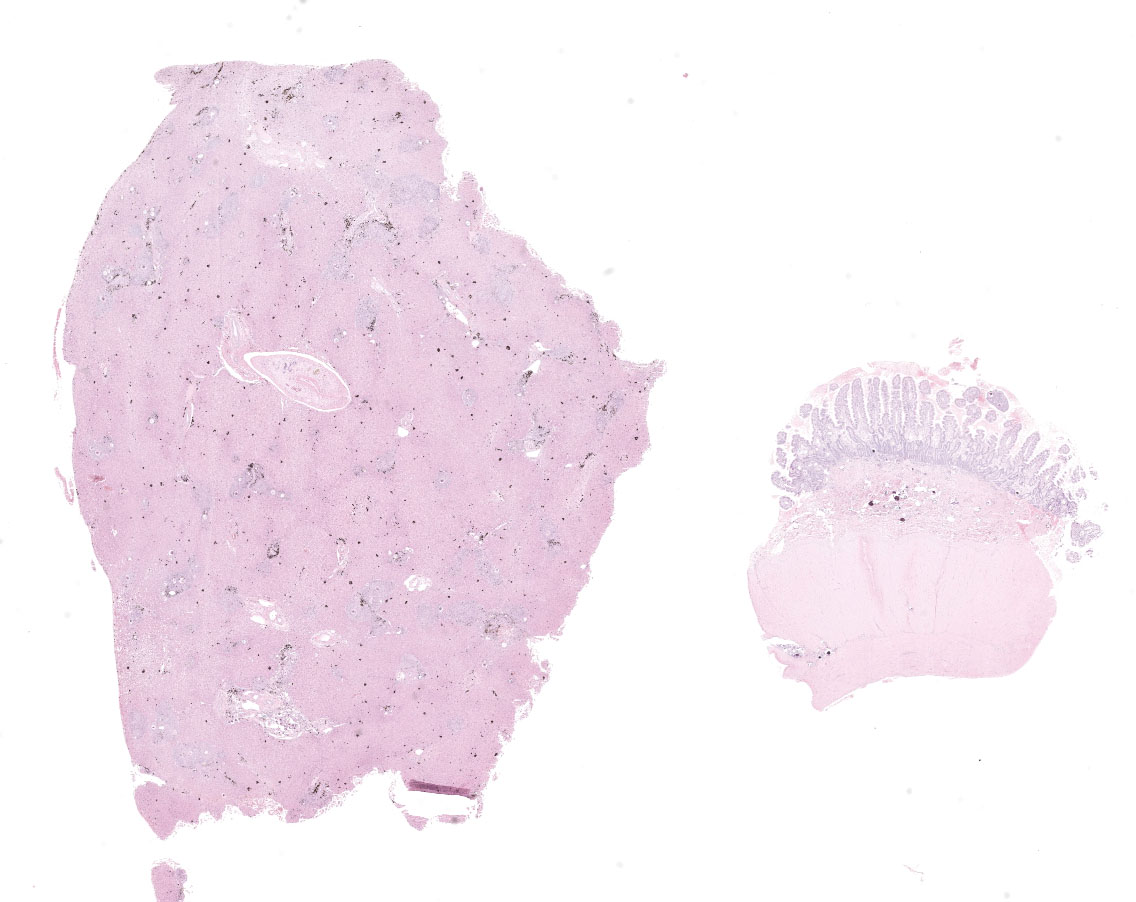

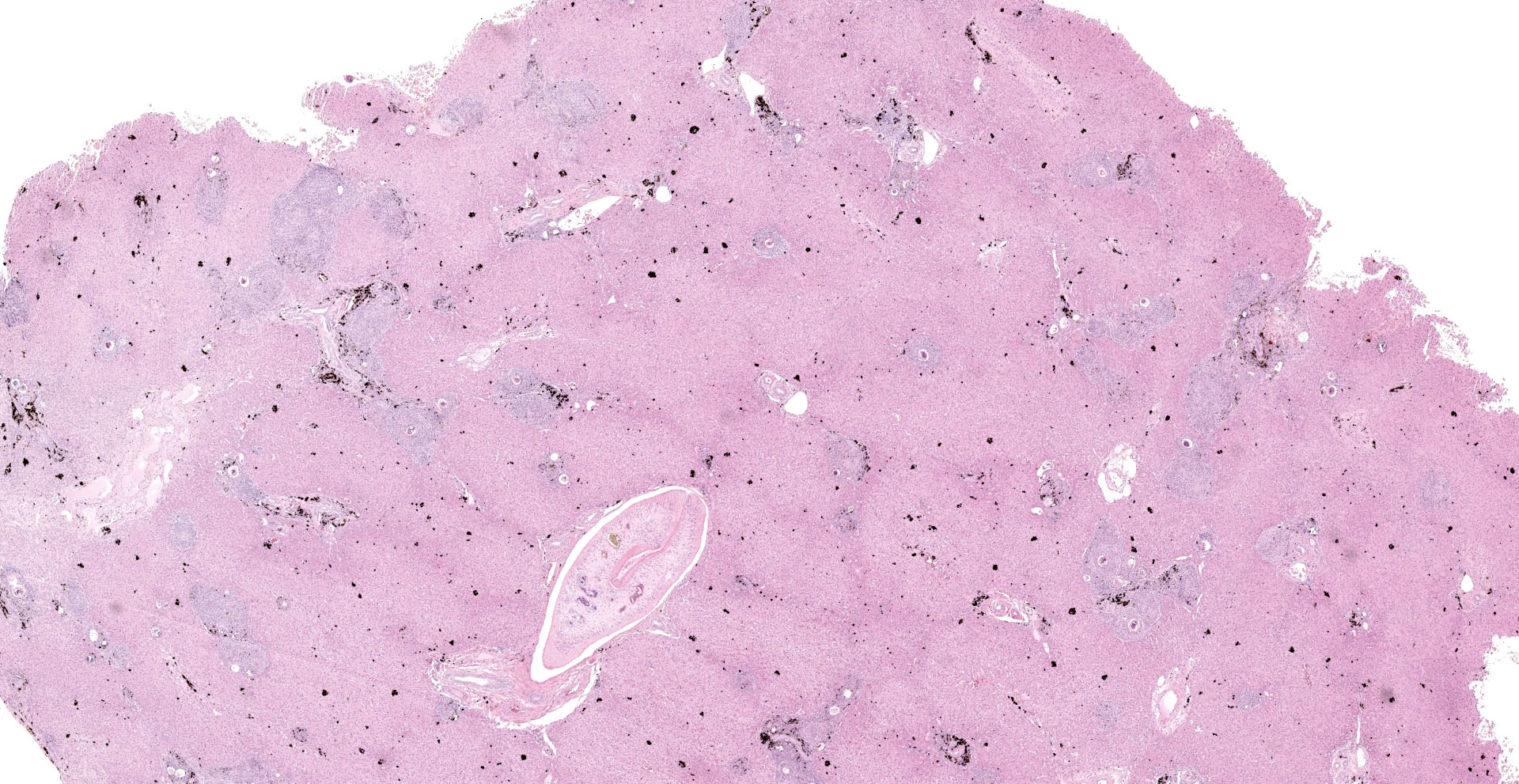

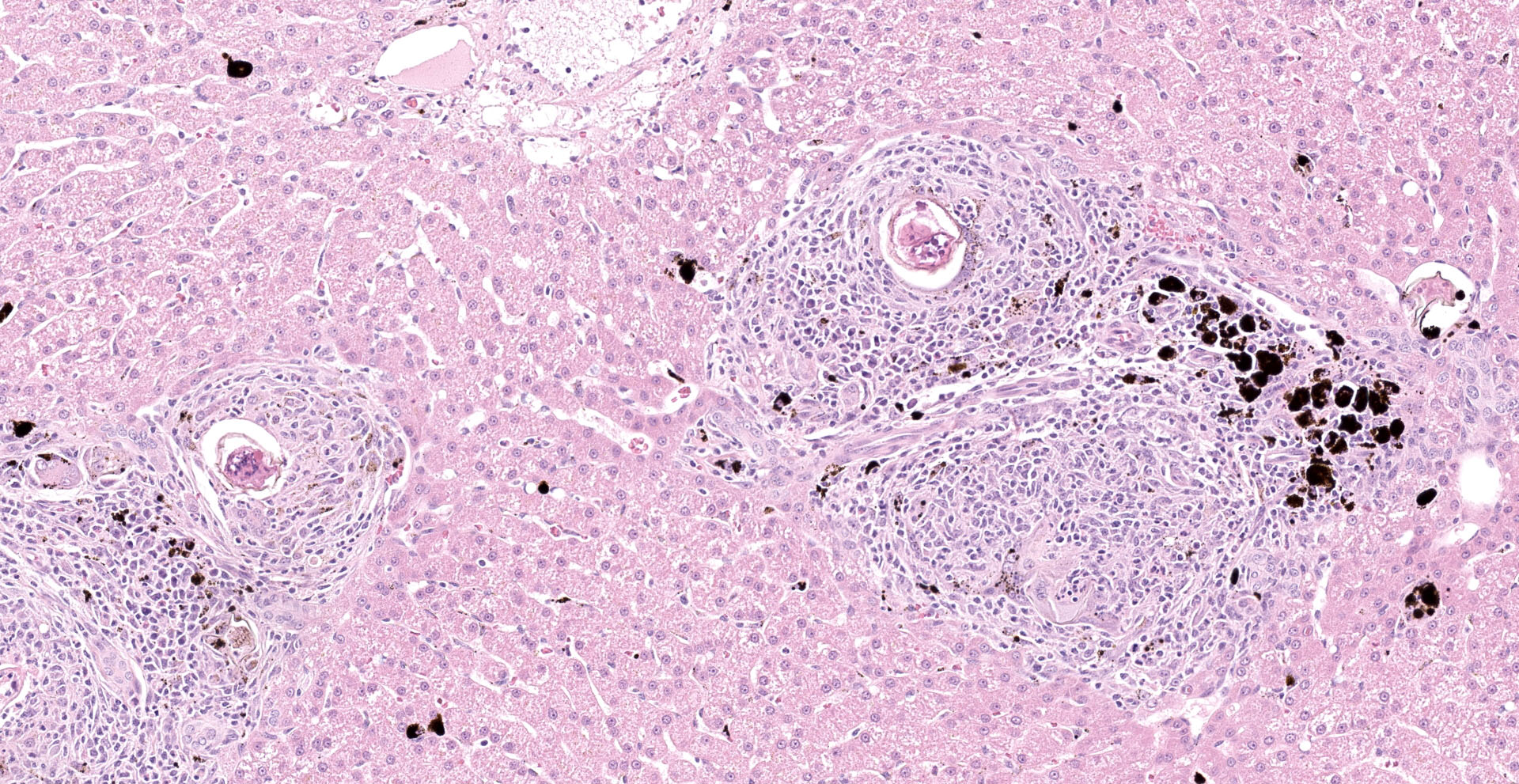

Microscopic Description:

Liver: Examined is a single section of a liver wedge biopsy, with minimal crush artifact. Throughout the section, portal tracts and random areas of the parenchyma are moderate to severely expanded by multiple nodular aggregates of macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils, often centering on up to 80 µm diameter, round to irregular to folded trematode eggs (granulomas). The eggs are characterized by a yellow-clear, up to 2 µm thick, hyalinized wall, with multiple, approximately 5 µm diameter, round and larger, irregular basophilic structures (miracidium). Occasionally, the eggs are replaced by irregular, clumped, deeply basophilic concretions (mineralization). A single portal vein is severely dilated and contains an approximately 200 µm wide male trematode. The trematode is characterized by a pale eosinophilic tegument with unevenly spaced, 4 µm wide and up to 18 µm long, hyalinized eosinophilic spines that are most concentrated in the anterior segment, spongy parenchyma, intestine filed with coarsely granular, golden-brown pigment (hemosiderin) and neutrophils, testes, and vitellaria (the trematode is found in 104/155 slides). The infiltrating macrophages are often laden with coarsely granular, black-brown cytoplasmic pigment (parasitic exhaust/"fluke pigment"). The nodular inflammatory aggregates are associated with streaming bundles of collagen (fibrosis) with increased numbers of irregular biliary profiles that occasionally lack a central lumen (ductular reaction). Diffusely, hepatic lobules are slightly small, and hepatocytes are similarly small and binucleated. Hepatocytes often contain moderate amounts of finely granular, brown-yellow cytoplasmic pigment (lipofuscin). Additionally, midzonal hepatocytes are minimally distended with variably sized, poorly demarcated cytoplasmic clear spaces separated by thin eosinophilic wisps extending from the cell membrane to the nucleus (glycogen).

Ileum: Examined is one ileal full-thickness specimen with minimal crush artifact. Within the lamina propria, submucosa, and muscularis are dozens of intact and mineralized trematode eggs, as described previously. The eggs are often surrounded by small numbers of macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, where multinucleated giant cells occasionally contain the trematode eggs (phagocytosis). These inflammatory cells together with small numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils, moderately infiltrate the lamina propria of the villus tips and deep mucosa. The connective tissue of the mid-mucosa is expanded by wispy, pale eosinophilic material and clear spaces (edema). The crypts are often elongated and slightly tortuous with increased numbers of mitotic figures, stacking of nuclei, and decreased numbers of goblet cells (crypt hyperplasia). The villus to crypt ratio is within normal limits at approximately 2:1.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Liver: Moderate, portal and random, chronic granulomatous and eosinophilic hepatitis with intralesional trematode eggs and adult trematode, portal fibrosis, ductular reaction, and fluke pigment deposition, consistent with schistosomiasis

Ileum: Moderate, generalized, chronic granulomatous enteritis and myositis with intralesional trematode eggs, mid-mucosal edema, and crypt hyperplasia, consistent with schistosomiasis.

Contributor's Comment:

Canine schistosomiasis is caused by Heterobilharzia americana, a digenean trematode in the family Schistosomatidae. These trematodes are unique in that they are not hermaphroditic and have separate sexes, the eggs are non-operculated, and the metacercariae are not encysted. The males have a gynecophoral canal that holds the females. Historically, H. americana was thought to be endemic to the South Atlantic and Gulf Coast regions of the United States, but recent reports indicate that the distribution of this parasite and natural occurrence in the domestic dog is broader than previously known, especially in the Midwestern United States including Kansas and Indiana.6,7,12 The present case is also a dog from Illinois, without known travel history, further supporting the recent spread of distribution.

The life cycle of Heterobilarzia is complex, where asexual reproduction occurs in a lymnaeid snail and sexual reproduction in a mammalian host. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are considered the most important natural definitive host,1 although a variety of other species such as wild and domestic canids, nutria (Myocastor coypus), and bobcats (Lynx rufus) may also be infected.10 In species of veterinary importance, infection in horses occur at a relative regularity resulting in hepatic, intestinal serosal, and mesenteric granulomas.4 Infection is rare in other equids and domestic species with single case reports in a Grant's zebra (Equus burchelli boehmi)13 and llama (Lama glama),3 respectively.

Dogs are exposed to infection when swimming or wading in freshwater infested with lymnaeid snails, where cercariae emerging from the snails penetrate the dog's skin by proteolytic enzymes secreted by the acetabulum glands. Subsequently, the cercariae will detach their tail and become schistosomules that spread to the lungs and then to the liver hematogenously, where sexual maturation occurs, and the adult trematodes will migrate to the mesenteric vein through the portal system for sexual reproduction. Schistosomiasis is mainly due to egg-induced tissue reaction (mainly TH2 response), while the adults elicit minimal host response. Occasionally, adult trematodes induce eosinophilic endophlebitis, intimal proliferation, and thrombosis in mesenteric and portal veins.11 In the presented case, in addition to the liver and ileum, similar granulomatous lesions associated with eggs were found in the concurrently submitted duodenum, jejunum, and mesenteric lymph node, but not in the stomach.

Clinical signs in infected dogs are usually nonspecific, and may include diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss, and anorexia.5 Clinicopathologic findings are also usually nonspecific, including hyperglobulinemia, increased liver enzyme activities, and eosinophilia.5 The prognosis for treated dogs is generally positive, while the disease is often fatal in severely infected dogs despite aggressive treatment. The outcome of the presented case is unknown.

Dogs in other parts of the world may get infected with other members of Schistosomatidae, such as Schistosoma japonicum and S. mansoni. Other schistosomes of veterinary importance include Orientobilharzia spp., affecting ruminants, and some species of avian schistosomes such as Trichobilharzia spp.

Contributing Institution:

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine,

Department of Biomedical Sciences,

Section of Anatomic Pathology,

New York State Animal Health Diagnostic Center

https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatitis, portal, granulomatous, chronic, diffuse, marked with numerous trematode eggs, fluke pigment, and an intravascular adult schistosome.

2. Small intestine: Enteritis, granulomatous, multifocal, moderate with numerous mucosal and submucosal trematode eggs.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of the host range, life cycle, pathogenesis, clinical signs, and histomorphologic features of the digenean trematode Heterobilharzia americana.

H. americana is endemic in the southeastern United States with northward extension along the Atlantic coast to the Carolinas. This distribution closely corresponds to the geographic range of the only species snail historically confirmed to be susceptible to infection by H. americana, the semi-tropical Galba cubensis. However, a second amphibious snail species, G. humilis, was recently discovered to also be susceptible to both experimental and natural H. americana infection. Unlike G. cubensis, G. humilis is widespread throughout North America. Furthermore, G. humilis was recently implicated in the westernmost H. americana outbreak to date, with infections reported in 12 dogs living near a man-made pond in Moab, Utah. Although G. cubensis has been reported as far north as Oklahoma, it is possible other species, such as G. humilis, are associated the sporadic infections in northern states such as Indiana and Illinois. G. humilis also serves as one of several intermediate host's for Fasciola hepatica, a trematode that inhabits the bile ducts of sheep and cattle, causing cholangiohepatitis.8

G. cubensis and G. humilis are closely related to at least 40 subspecies and species of "fossarine" lymnaeids, which are relatively small snails with shell heights of less than 15mm and typically live very close to or above the waterline but may also be completely submerged. Collectively, fossarine lymnaeids are distributed throughout much of North America, the Caribbean, and regions of Central and South America. Given their close genetic relationship, multiple Galba spp., in addition to those previously identified, may potentially serve as intermediate hosts for H. americana, though additional research is needed to verify this hypothesis.8

Interestingly, infective cercariae are released from snails under nocturnal conditions. This is an indication of a host-adaptation of H. americana for the common raccoon (Procyon lotor), which typically forages in and around aquatic habitats during the night. Furthermore, the westward expansion of H. americana may be partially due to an increase in the raccoon's range itself, as this opportunist was not commonly found in the American west until the 20th century as the result of urbanization, decreased predation, climate change, and expanding agriculture. Although H. americana's maintenance and gradual expansion is facilitated by the raccoon, infected dogs imported from endemic regions also may play a major role in its introduction to distant new habitats.8

Humans are also affected by H. americana, which causes severe cercarial dermatitis, also known as "swimmer's itch", but does not result in patent infection.8 However, humans are very commonly parasitized by other schistosomes, making schistosomiasis the second most common parasitic disease of humans worldwide, following malaria. The most common species known to infect humans are Schistosoma mansoni, S. haematobium, and S. japonicum.

Schistosomiasis has plagued mankind for millennia, as symptoms consistent with S. haematobium were described on ancient Egyptian papyrus and calcified S. haematobium eggs were recovered from 3,200 year old Egyptian mummies.9 Over two millennia later, Napoleon's troops referred to Egypt as the "land of menstruating males" as hematuria from schistosomal cystitis was so common that it was interpreted as an indication of puberty.2 The parasite was first described in humans by Theodore Bilharz in 1851. As a result, the condition is also commonly referred to as "bilharzia" or "bilharziasis".9

Schistosomiasis is estimated to cause approximately 280,000-500,000 deaths per year. In addition, schistosomiasis is associated with a tremendous morbidity rate, with over 250 million infections, resulting in an estimated loss of 3.3 million life-years per year according the DALYs index ("Disability-Adjusted Life Years"). Unfortunately, human schistosomiasis is grouped in a category of diseases known as "Neglected Tropical Diseases", which also includes several helminth, protozoal, viral, and bacterial diseases. These diseases predominately affect underserved populations living in the poorest conditions and contribute toward the maintenance of social inequality, inherently creating significant barriers for the development of the most severely affected countries.9

References:

1. Bartsch RC, Ward BC. Visceral lesions in raccoons naturally infected with Heterobilharzia americana. Vet Pathol. 1976;13:241?249.

2. Cheever AW. Schistosomiasis and neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978;61(1):13-18.

3. Corapi WV, Eden KB, Edwards JF, Snowden KF. Heterobilharzia americana infection and congestive heart failure in a llama (Lama glama). Vet Pathol. 2015;52:562?565.

4. Corapi WV, Snowden KF, Rodrigues A, et al. Natural Heterobilharzia americana infection in horses in Texas. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:552?556.

5. Graham AM, Davenport A, Moshnikova VS, et al. Heterobilharzia americana infection in dogs: A retrospective study of 60 cases (2010-2019). J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:1361?1367.

6. Hanzlicek AS, Harkin KR, Dryden MW, et al. Canine schistosomiasis in Kansas: five cases (2000-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:e95?e102.

7. Johnson EM. Canine schistosomiasis in North America: an underdiagnosed disease with an expanding distribution. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2010;32:E1?E4.

8. Loker ES, Dolginow SZ, Pape S, et al. An outbreak of canine schistosomiasis in Utah: Acquisition of a new snail host (Galba humilis) by Heterobilharzia americana, a pathogenic parasite on the move. One Health. 2021;13:100280.

9. LoVerde PT. Schistosomiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1154:45-70.

10. McKown RD, Veatch JK, Fox LB. New locality record for Heterobilharzia americana. J Wildl Dis. 1991;7:156?160.

11. Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie GM, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 3. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016.

12. Rodriguez JY, Camp JW, Lenz SD, Kazacos KR, Snowden KF. Identification of Heterobilharzia americana infection in a dog residing in Indiana with no history of travel. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;248:827?830.

13. Rodriguez JY, Finneburgh BM, Lewis BC, Flanagan J, Snowden KF. Heterobilharzia americana infection in a Grant's zebra (Equus burchelli boehmi). Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2021;23:100495.