Signalment:

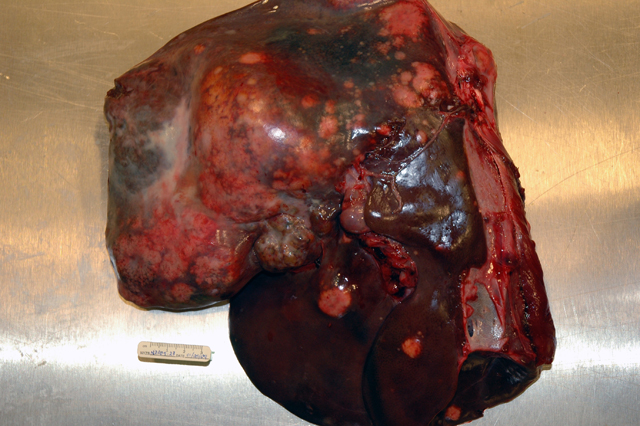

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

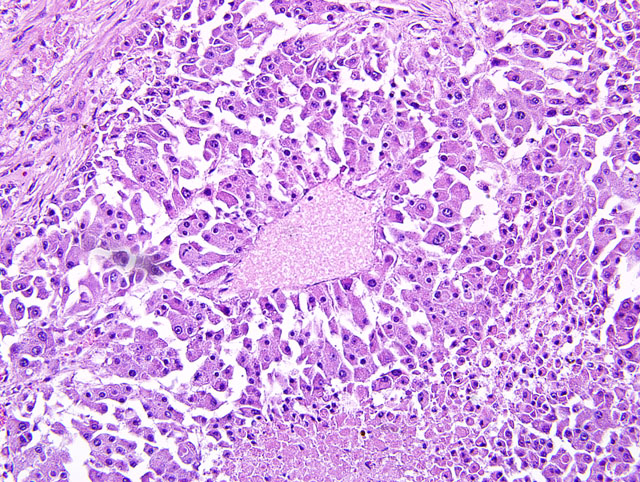

Liver: Approximately 40% of the preexistent hepatic parenchyma is effaced, compressed and replaced by a focally extensive, unencapsulated, vagely lobulated, infiltrative nodular mass. The mass is composed of irregular cords and trabeculae of polygonal cells with discrete cytoplasmic borders, abundant finely granular cytoplasm and a single to occasionally multiple round to elongated vesicular nuclei with coarsely clumped chromatin and one to multiple prominent nucleoli. Neoplastic cells display marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, marked nuclear atypia and a low mitotic rate (1-2 mitoses per 10 40X fields). Separating the neoplastic cells into lobules and nests is a pervasive, densely cellular fibrous connective tissue stroma that occasionally contains atrophied ductular structures. Within central areas of the mass there are regions of loss of cellular detail and differential staining that are replaced with cellular and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis). Peritumoral hepatic cords are compressed and there is variable congestion and hemorrhage (not present in all slides). Single and small clusters of pigment-laden macrophages (hemosiderophages fig. 2) are present throughout the section both within the sinusoids as well as associated with portal regions.

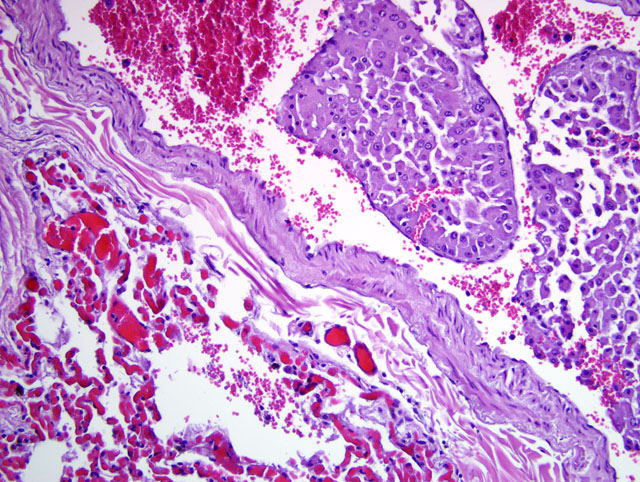

Lung: Effacing approximately 30% of the pulmonary tissue is a focally extensive, unencapsulated, vaguely lobulated, infiltrative nodular mass. The neoplastic cells display morphologic features consistent with the neoplastic cells previously described in the liver. In addition, variably prominent throughout the sections, clusters of neoplastic cells are present within the lumen of vascular structures (neoplastic emboli) and often extend into and adjacent alveolar spaces. In sections of lung from the cranioventral lobes (slide B) there is marked hemorrhage and edema that obscure most of the alveolar spaces accompanied by peribronchiolar, intralumenal and intraalveolar dense aggregates of viable and degenerate neutrophils and macrophages that contain ingested erythrocytes as well as coarse, golden yellow pigment granules (hemosiderin).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatocellular carcinoma, pseudoglandular, regionally extensive, severe with fibrosis, intratumoral necrosis and perilesional parenchymal compression and hemorrhage.

2. Liver: Hemosiderosis, chronic, multifocal, mild to moderate.

3. Lung (all slides): Hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic, regionally extensive, severe with intratumoral necrosis and hemorrhage and multifocal vascular tumor emboli.

4. Lung (slide B): Pneumonia, bronchointerstitial, acute to subacute, regionally extensive, moderate to severe with regionally extensive hemorrhage, edema, fibrin, erythrophagocytosis and hemosiderin deposition.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Intrahepatic metastases are common and vascular, rather than lymphatic invasion, is more typical in these tumors.(2,10) Metastatic spread to the lungs and to lymph nodes within the cranial abdomen is also a feature of this neoplasm, as is invasion of the hepatic capsule and seeding of the peritoneal cavity.(1,2,10) Rupture of these neoplasms can occur spontaneously (10) and, as in this case, can result in a fatal intraabdominal hemorrhage; however, rupture of the tumor in this deer may have resulted from aggressive or dominant behavior between individuals in the herd. In addition, at the time of the necropsy there was evidence of mild aspiration pneumonia (not represented in all slides) that may have also been the result of repeated harassment or trauma by other members of the herd in the hours to days prior to death.

The etiology of most hepatocellular carcinomas is unknown. Numerous chemical compounds used in industrial and/or experimental settings have been linked to the development of hepatic neoplasia in humans and laboratory animals, but significant exposure of these to domestic and wild animal species is unlikely.(1) Naturally occurring toxic compounds, such as aflatoxins, pyrrolizidines and nitrosamines, and infectious agents, such as hepatitis B viruses, woodchuck hepatitis virus and Helicobacter spp. in some strains of mice, have been implicated in hepatic carcinogenesis.(1) Dietary factors and availability of foraging substrates are also suspected of playing a role in the increased incidence of hepatocellular carcinomas within geographically distinct populations of roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in Britain.(3,7)

In non-domestic species, hepatocellular carcinomas have been reported in black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludivicianus) and other members of the Sciuridae family, in which a viral etiology is suspected.(5) Nearly all woodchucks (Marmota marmota) infected with the woodchuck hepatitis virus are known to develop hepatocellular carcinoma.(1) In cervids, hepatocellular carcinomas have been reported in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).(3,7,8) Other neoplasms reported in cervids include spontaneous abomasal and uterine adenocarcinomas in an elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni)4, cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma in a juvenile fallow deer (Dama dama) (6), and uterine adenocarcinoma in a sika deer (Cervus nippon).(9)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

2. Lung: Hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic.

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Cullen JM: Liver, biliary system, and exocrine pancreas. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Diseases, ed. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 450-451, 2007

3. De Jong CB, Van Wieren SE, Gill RMA, Munro R: Relationship between diet and liver carcinomas in row deer in Kielder Forest and Galloway Forest. Vet Rec 155(7):197-200, 2004

4. Duncan C, Powers J, Davis T, Spraker T: Abomasal and uterine adenocarcinomas in a captive elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni). J Vet Diagn Invest 19(5):560-563, 2007

5. Garner MM, Raymond JT, Toshkov I, Tennant BC: Hepatocellular carcinoma in Black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludivicianus): Tumor morphology and immunohistochemistry for hepadenavirus core and surface antigens. Vet Pathol 41:353-361, 2004

6. Kolly C, Bidaut A, Robert N: Cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma in a juvenile fallow deer (Dama dama). J Wild Dis 40(3):603-606, 2004

7. Munro R, Youngon RW: Hepatocellular tumours in roe deer in Britain. Vet Rec 138:542-546, 1996

8. Placke ME, Roscoe DE, Wyand DS, Nielsen SW: Hepatocellular adenocarcinoma in a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Can J Comp Med 46(2):198-200, 1982

9. Robert N, Pothaus H: Uterine adenocarcinoma in a captive sika deer. J Wild Dis 35(1):141-144, 1999

10. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 384. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007