WSC 2023-2024, Conference 14, Case 1

Signalment:

Adult female Norwegian Fjord horse (Equus caballus)

History:

This horse was born near Hanover, Germany. It was kept solely in northern Germany and has never been abroad. It was presented to the local veterinarian due to lameness. During the clinical examination, the veterinarian detected multiple cutaneous nodules. Two representative samples (elbow and periorbital skin) were surgically excised, fixed in 10% formalin, and submitted for histological examination.

Gross Pathology:

In both samples, the haired skin showed focal alopecia, focal ulceration, and poorly demarcated lumps with a size of up to 1.2 cm in diameter.

Laboratory Results:

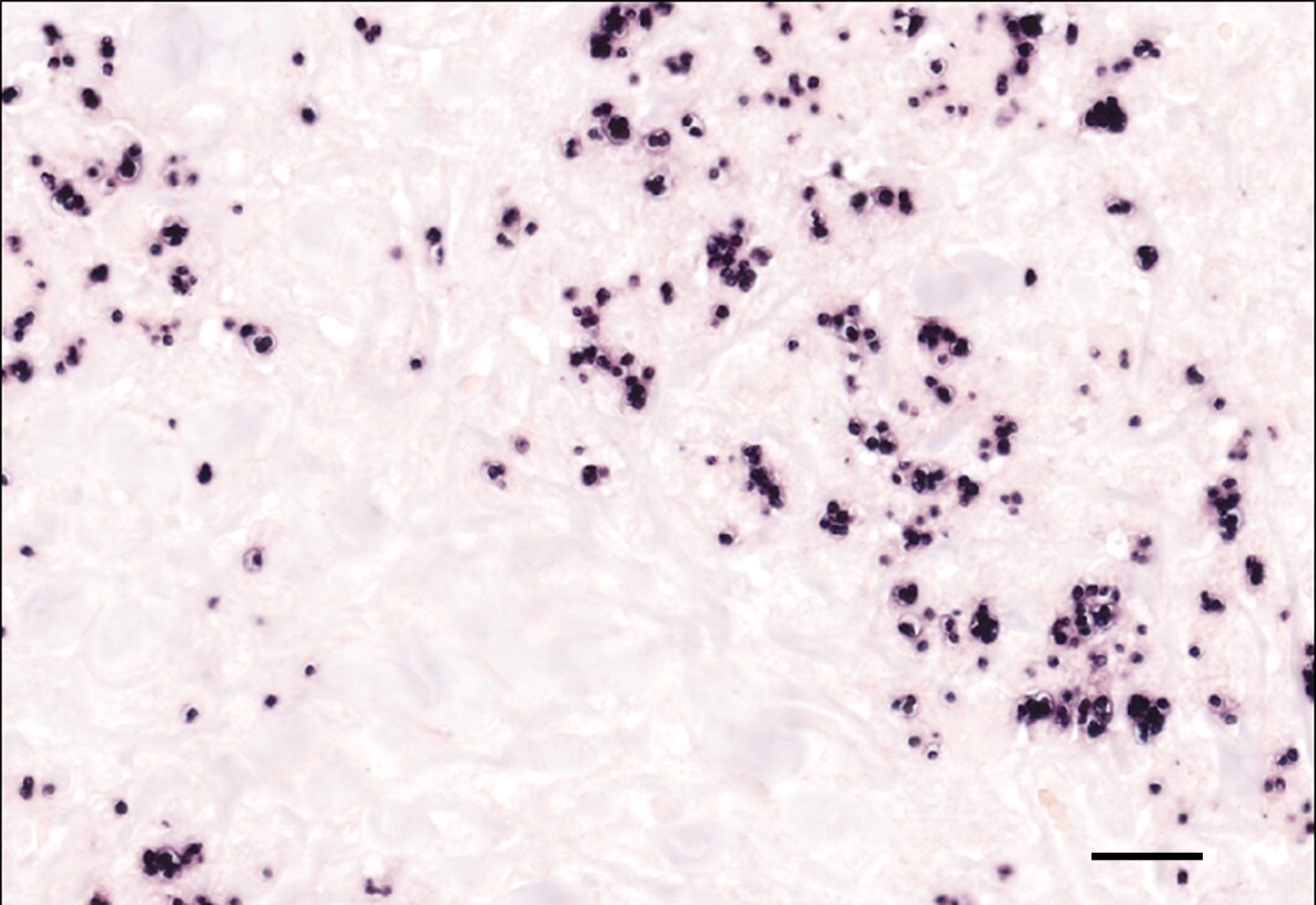

Genome fragments of Leishmania sp. were detected in the cytoplasm of multinucleated giant cells and macrophages using in situ hybridization.

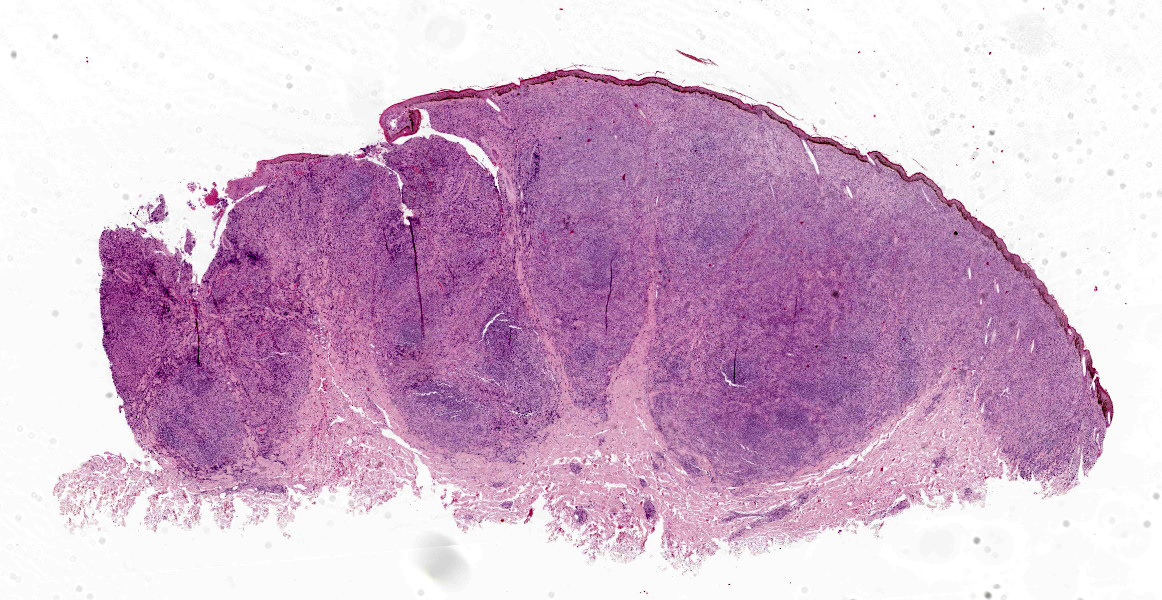

Microscopic Description:

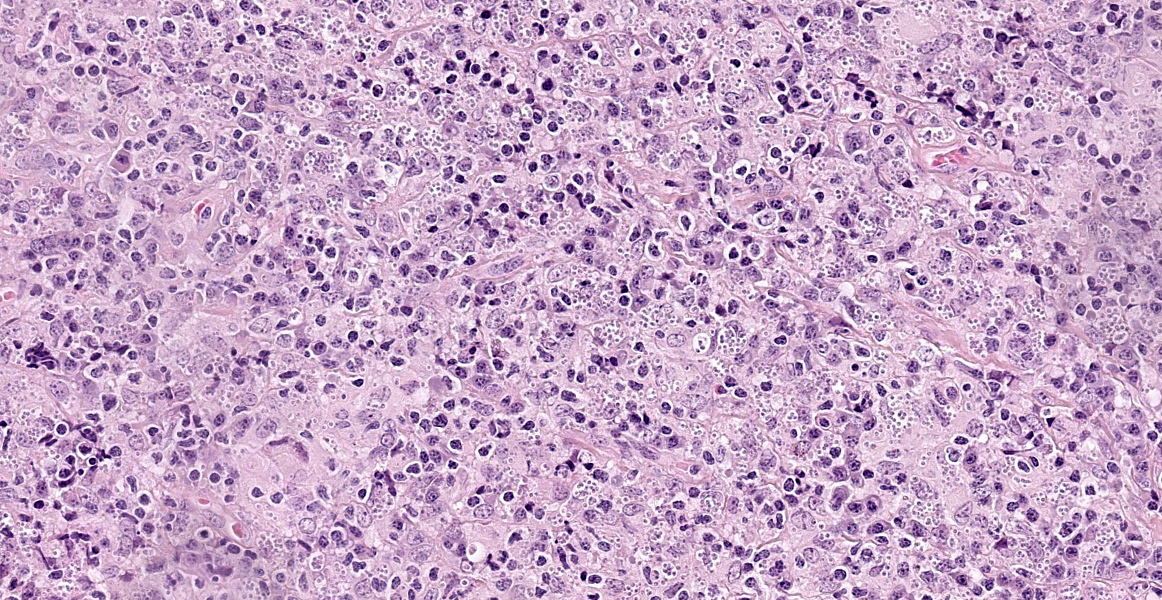

Haired skin: The superficial and deep dermis shows a multifocal to coalescing periadnexal and a multinodular to coalescing severe inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of myriad

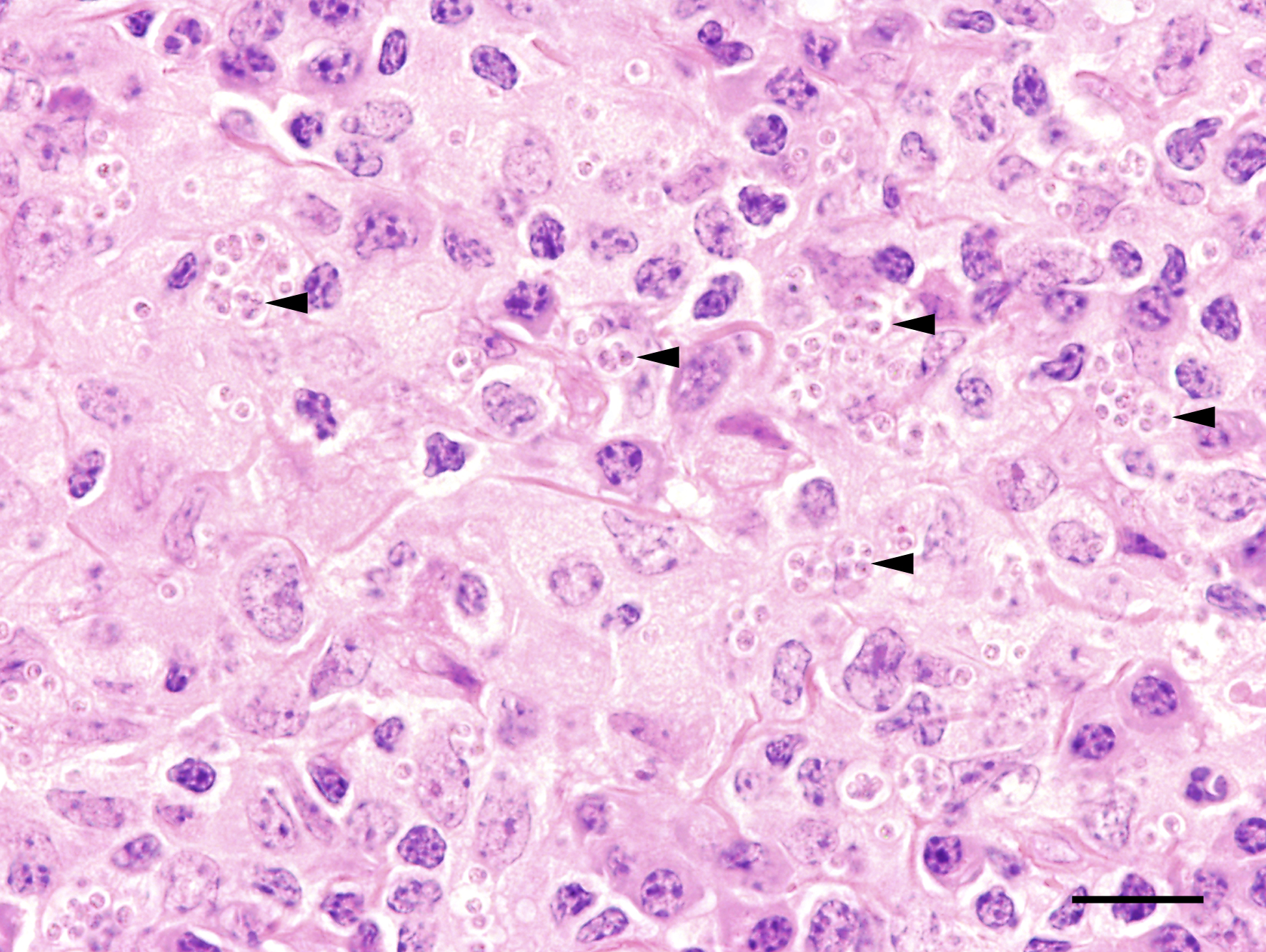

macrophages admixed with low to moderate numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes, as well as single eosinophilic granulocytes. Randomly distributed throughout the whole lesion, there are multinucleated giant cells with a size of up to 50 µm in diameter, containing up to 10 predominantly peripherally located nuclei (Langhans type). Occasionally in the extracellular space, but predominantly and frequently within the cytoplasm of macrophages, there are multiple protozoal structures (amastigotes) with a diameter of 2 to 3 µm often surrounded by a clear halo suggestive of a clear parasitophorous vacuole. The round organisms are characterized by a clear cytoplasm and a single eccentric nucleus of approximately 1-2 µm diameter. Furthermore, in the superficial dermis, fibroblastic connective tissue is moderately hyperplastic. In addition, low numbers of macrophages with brown-black intracytoplasmic pigment are present in the subepidermal tissue (pigmentary incontinence). Occasionally, hair shafts and sebaceous glands are missing.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, chronic, severe, focally extensive, periadnexal to diffuse, granulomatous, with multinucleated giant cells (Langhans type) and intrahistiocytic protozoal amastigotes, equine.

Contributor?s Comment:

Leishmaniasis is a globally occurring infectious disease in humans and animals caused by obligate intracellular protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania. The disease is endemic in Southern Europe, North Africa, South and Central America, and Asia.13 In Europe, it occurs mainly in the Mediterranean region. Due to increased travel activities with companion animals, the number of animals infected with Leishmania sp. in Northern Europe has increased. Additionally, since the 1980s, the sandflies that transmit leishmaniasis have increasingly appeared in Northern Europe, especially in Germany, possibly due to climate change.1,8 This has initiated the discussion about the occurrence of autochthonous cases of leishmaniasis in Europe north of the Alps.7

Leishmania sp. require both arthropods and vertebrates for their development. Sandflies such as Phlebotomus sp. and Lutzomyia sp. play an important role as vectors of Leishmania sp. in Europe and South and Central America.1 The amastigote form of Leishmania sp. is found in the cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system of vertebrates, predominantly in liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. Occasionally, the organisms are detected in other leukocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and neoplastic cells.2,10 After ingestion of macrophages containing Leishmania amas-tigotes by a female arthropod during a blood meal, the amastigotes are transformed into promastigotes in the intestine and subsequently enter the biting mouthparts of the arthropod.13,18 Transmission of the pathogen through either mechanical vectors such as bloodsucking insects and ticks or a direct and vertical transmission has also been reported.6,11,18

There are more than 50 species of Leishmania based on a complex classification scheme. The species of Leishmania vary by region, and different species are thought to cause different disease manifestations.1 Currently,three different Leishmania sp. have been confirmed to cause cutaneous leishmaniasis in horses in Europe: Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania siamenis, and Leishmania infantum.14

In animals and humans, leishmaniasis can cause three different disease patterns: cutaneous leishmaniasis, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, and visceral leishmaniasis.13 Clinical signs of equine cutaneous leishmaniasis are usually less severe than in other host species and the disease in equids is typically not life-threatening. The most common lesions are single or multiple papules or nodules characterized by hyperkeratosis with prominent scaling, alopecia, depigmentation, and ulceration in the areas where sand flies commonly feed, including periorbital skin, muzzle, neck, pinnae, scrotum, and legs.13,14

Histologically, a nodular to diffuse lympho-histiocytic dermatitis is a consistent feature of cutaneous leishmaniasis.14 The inflammation mainlyvoccurs in one of the following three patterns: granulomatous perifolliculitis, super-ficial and deep perivascular dermatitis, or interstitial dermatitis.13 However, the burden of the protozoa may vary. This reflects the dynamics of the interaction between the host and the pathogen. Moreover, the incubation time of cutaneous leishmaniasis varies from several months up to seven years.13 Spontaneous regression and recurrence of cutaneous leishmaniasis have been reported in cats and horses.15

Not all infected animals become ill. In infected animals, leishmania-specific and non-specific polyclonal B-cell activation may occur, which can lead to deposition of immune complexes and formation of autoantibodies against erythrocytes, platelets, and nuclear antigens. In diseased animals, a Th2-immune response predominates. In contrast, a type IV hypersensitivity reaction and a Th1-immune response are found in asymptomatic carriers or in animals after successful chemotherapy.13

Due to the variety of possible lesions and the various infectious and noninfectious differential diagnoses, the diagnosis of leishmaniasis requires direct cytologic or histological identification of amastigotes in the cytoplasm of macrophages, best visible by Giemsa staining.13 Furthermore, pathogen detection is possible by immunohistological, culture, and molecular (PCR and in situ-hybridization) detection methods.3,12 A positive serological test indicates that an infection has occurred, but does not imply that the parasite is still present in the infected host.3

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology

University of Veterinary Medicine, Hannover

Buenteweg 17, 30559

Hannover, Germany.

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with numerous intrahistiocytic amastigotes.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of leishmaniasis, a zoonotic disease most consistently found in humans and dogs and which has not historically been considered endemic in the United States. In recent decades, cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis has been reported among certain canine breeds in the United States and Canada, and cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis have been reported in U.S. horses without a history of travel to endemic areas.16,17

The first documented report of a domestically acquired case of equine leishmaniasis occured in a Morgan horse mare in Florida in 2011.4,16 As noted by the contributor, the canonical mode of transmission of Leishmania sp. is via the bite of sandflies from the genera Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia, and Florida is host to two possible sand fly vectors, Lutzomyia shannoni and Lutzomyia vexator.17 Lutzomyia shannoni is known to feed on both humans and other mammals, and it has been experimentally shown capable of infection with Leishmania infantum when fed on infected dogs; however, it is not known if the infective amastigote forms develop within Lutzomyia shannoni.17 The search for a competent sandfly vector may be superfluous, however, as recent research has demonstrated that the species of Leishmania isolated from infected Florida horses, Leishmania martiniquensis, is likely transmitted by Culicoides spp. biting midges.5,9,17 Due to the presence of competent vectors in the United States and a small but growing number of confirmed cases of domestically-acquired equine leishmaniasis, the American Association of Equine Practitioners recently released guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.4

Equine cutaneous leishmaniasis commonly presents as solitary or multiple ulcerated nodules on the head, pinnae, scrotum, legs, and neck.17 To date, equine leishmaniasis has been confined to the skin and the more serious and potentially fatal visceral form of the disease seen in dogs and humans has not been reported in horses; most clinical equine cases spontaneously resolve in 3-6 months and the prognosis is therefore generally good.4,17

This week?s conference was moderated by Joint Pathology Center Director and equestrian enthusiast LTC(P) Sherri Daye. LTC(P) Daye led conference participants in a discussion of the differences among molecular diagnostic techniques such as in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry before moving to differential diagnoses. Participants were even-ly split between Histoplasma capsulatum and Leishmania spp. as the likely etiologic agent of this lesion, and significant conference discussion focused on how to differentiate between the two organisms when presented with only an H&E section. Participants noted that leishmaniasis typically presents with abundant plasmacytic inflammation, which is absent in this case. In addition, the clear capsule-like rings surrounding the organisms are unusual in leishmaniasis and further contributed to the diagnostic confusion.

Though cutaneous leishmaniasis has not historically been top of mind in the United States and Northern Europe, the incidence of this disease is likely to increase as competent vectors, driven by migratory movements of people and animals and climate change, move into newly favorable geographic niches.

References:

- Akhoundi M, Kuhls K, Cannet A, et al. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of Leishmania parasites and sandflies. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004349.

- Albanese F, Poli A, Millanta F, et al. Primary cutaneous extragenital canine transmissible venereal tumour with Leish-mania-laden neoplastic cells: a further suggestion of histiocytic origin? Vet Dermatol. 2002;13:243?246.

- Albuquerque A, Campino L, Cardoso L, et al. Evaluation of four molecular methods to detect Leishmania infection in dogs. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:57.

- American Association of Equine Prac-titioners. AAEP Infectious Disease Guidelines:Equine Cutaneous Leish-maniasis. 2022. Available at https://aaep .org/document/equine-cutaneous-leish-maniasis.

- Becvar T, Vojtkova B, Siriyasatien, et. al. Experimental transmission of Leishmania (Mundia) parasites by biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). PLos Pathog. 2021;17(6):e1009654.

- Bogdan C, Schönian G, Bañuls AL, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in a German child who had never entered a known endemic area: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:302-306.

- Dujardin JC, Campino L, Canavate C, et al. Spread of vector-borne diseases and neglect of leishmaniasis, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1013?1018.

- Harms G, Schönian G, Feldmeier H. Leishmaniasis in Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:872-875.

- Kaewmee S, Mano C, Phanitchakun T, et al. Natural infection with Leishmania (Mundia) martiniquensis supports Culicoides peregrinus (Diptera: Cerat-opogonidae) as a potential vector of leishmaniasis and characterization of a Crithidia sp. isolated from the midges. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1-17.

- Kegler K, Habierski, A, Hahn, H, et al. Vaginal canine transmissible venereal tumour associated with intra-tumoural Leishmania spp. amastigotes in an asymptomatic female dog. J Comp Pathol. 2013;149:156-161.

- Koehler K, Stechele M, Hetzel U, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniosis in a horse in southern Germany caused by Leishmania infantum. Vet Parasitol. 2002;109:9-17.

- Maia C, Campino L. Methods for diagnosis of canine leishmaniasis and immune response to infection. Vet Parasitol. 2008;158:274?287.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integ-umentary System. In: Maxie G, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer`s Pathology of Dom-estic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 1. Elsevier; 2016:240.

- Mhadhbi M, Sassi A. Infection of the equine population by Leishmania para-sites. Equine Vet J. 2020;52:28-33.

- Müller N, Welle M, Lobsiger L, et al. Occurrence of Leishmania sp. in cutan-eous lesions of horses in Central Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:346-351.

- Petersen CA, Barr SC. Canine leish-maniasis in North America: emerging or newly recognized? Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39(6):1065-1074.

- Reuss SM. Review of equine cutaneous leishmaniasis: not just a foreign animal disease. AAEP Proceedings. 2013;59:256-260.

- Serafim TD, Coutinho-Abreu IV, Dey R, et al. Leishmaniasis: the act of trans-mission. Trends Parasitol. 2021;37: 976-987.