Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 24

29 April, 2020

CASE IV: WSC Case 2 (DVD) (JPC 4083951). Tissue from a horse (Equus caballus).

Signalment: 26-year-old male horse (Equus ferus caballus), breed not documented

History: This horse was part of a protocol for which blood samples were collected periodically to provide blood and/or blood products for use in other research projects. The horse was ataxic, lethargic, and exhibited reported neurologic signs for approximately 2 days prior to being euthanized.

This horse was part of a research project conducted under an IACUC approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facility where this research was conducted is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and adheres to principles stated in the 8th edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

Gross Pathology: Due to extenuating circumstances and adverse weather conditions, the only portion of this animal harvested for necropsy was the head. Because the horse exhibited neurologic signs prior to euthanasia, both rabies and herpes tests were performed on postmortem brain samples at the local diagnostic laboratory, and were negative. Upon gross examination of the brain, it was noted that the pituitary gland was dark red, soft, and enlarged, measuring 2.5 x 2.5 x 3 cm.

Laboratory results: Rabies and herpes tests: Negative.

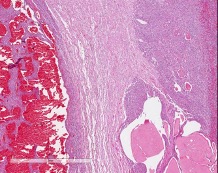

Microscopic Description: Pituitary gland: Expanding the pars intermedia, compressing adjacent tissue, is a well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, moderately cellular neoplasm composed of polygonal cells arranged in nests and packets supported by a fine fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells have indistinct cell borders, moderate amounts of granular, often microvacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, a round, antibasilar nucleus with finely stippled chromatin, and up to 3 variably distinct nucleoli. Mitosis average less than one per 10 HPFs. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild to moderate. Diffusely throughout the neoplasm, neoplastic cells often surround variably sized and shaped blood-filled cystic spaces and occasionally palisade around blood vessels, forming pseudorosettes. Neoplastic cells occasionally form follicles lined by low cuboidal cells and filled with homogenous eosinophilic material (colloid) and cellular debris. Occasionally, scattered throughout the neoplasm and adjacent pars nervosa, there are globules of gold-brown pigment (hemosiderin) and bright yellow pigment (hematoidin) accompanied by hemosiderin-laden macrophages. There is multifocal, minimal hemorrhage.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Pituitary gland, pars intermedia: Adenoma, breed unspecified, equine.

Contributor Comment: Adenoma of the pars intermedia is the most common pituitary tumor in the horse.1 Grossly, the tumors are well circumscribed, partially encapsulated, multinodular, space occupying lesions that tend to expand, and subsequently compress, the overlying hypothalamus.1 Microscopically, neoplastic cells are polygonal to spindle shaped with eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm, and an oval, hyperchromatic nucleus. Neoplastic cells are arranged in nodules, rosettes, bundles, or follicular structures separated by fine, fibrovascular septa, often containing numerous capillaries.1,4

Secondary compression of the hypothalamus can greatly diminish its normal function, resulting in the clinical syndrome associated with the tumor, termed Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID). PPID is one of the most commonly diagnosed equine endocrinopathies.7 PPID was originally imprecisely termed ?equine Cushing?s disease,? due to its similarities to human Cushing?s disease. However, in human Cushing?s disease, the pars distalis, rather than the pars intermedia, is affected. Additionally, in humans, the condition is usually not neoplastic, and exhibits more adrenal gland involvement.5 Since the hypothalamus is responsible for regulating body temperature, appetite, and cyclic shedding of hair, clinical signs in the horse include hyperhidrosis, polyphagia, hirsutism, polyuria, polydipsia, laminitis, muscle atrophy, fat accumulation, lethargy, and some metabolic abnormalities, among others.1,5,6,7 Hypothalamus compression and resultant PPID is not limited in causation to neoplasia, and can also result from pituitary hypertrophy and hyperplasia, with the pituitary gland enlarging 2 to 5 times its normal weight.5

There are conflicting reports whether there is a gender predisposition in horses with PPID. Historically, literature has reported that female horses are more frequently affected than males, while others have noted a weak association with gelding sex.54 Still other studies report no sex differences in the risk for developing PPID, including a review with meta-analysis of 6 studies.3 However, there is overall consensus that PPID is a chronic progressive disease that overwhelmingly affects older horses, and is considered one of the most common diseases of horses 15 years of age and older.5,6 The population of aged horses has considerably increased within the past two decades, and clients are becoming more informed and aware of equine age-associated diseases.5 A recent report that investigated disease prevalence in older horses found that pituitary pars intermedia adenoma was the most common neoplasm in horses 15 years of age and older, and that PPID was the most common specific diagnosis.6 Additionally, when accounting for the reason for euthanasia, PPID was found to be the second-most common cause of death in aged horses, with disease of the digestive system as the first.6

Note: Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

Contributing Institution:

USAMRIID

Pathology Division

1425 Porter Street

Frederick, MD 21702-5011

JPC Diagnosis: Pituitary gland, pars intermedia: Adenoma.

JPC Comment: The

contributor has provided a very concise but thorough review of this particular

neoplasm (largely restricted to the dog and horse), as well as the very

important and common condition of pars pituitary intermedia disease (PPID). It

bears repeating that the two entities are different, in that the pituitary pars

intermedia adenoma (PI adenoma) is a common neoplasm in older horses, while

PPID is the clinical syndrome arising from the compression of the hypothalamus

from neoplasms or hyperplastic lesions of the pituitary. Characteristic

clinical signs of PPID in the horse include hirsutism, delayed shedding,

polydipsia and polyuria, weiht loss, laminitis, and reproductive disorders in

mares.2

As histologic and stereologic study was performed on 124 horses, and a number

of histologic findings were significantly correlated with age, to include

follicles and cysts within the pars intermedia, lipofuscin in the pars nervosa,

and focal chromophobe hyperplasia in the pars glandularis. Highlighting the

difference between adenoma and PPID, in this study, 22/124 horses had adenomas

of the pars intermedia, but only 4/124 demonstrated clinical signs associated

with PPID. In this study, most PI adenomas were considered incidental findings

and non-functional. (Interestingly, in another review of old age lesions in

the horse, in a total of 40 horses with PI adenoma, 23 were euthanized because

of the pituitary adenoma. Interestingly, stereological review of PI adenomas

showed that the neoplastic cells of PI adenomas causing PPID were larger by

volume than those in horses without PPID.

Pituitary adenomas may also be part of a constellation of endocrine tumors in horses. In a recent multicenter study on equine pheochromocytoma, 18/37 (49%) animals had a concurrent PI adenoma, and 8/37 had a third neoplasm (thyroid adenoma, C-cell carcinoma), ultimately resulting in a diagnosis of multiple endocrine neoplasia. In humans, type I multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) includes pheochromocytoma and pituitary gland tumors.

References:

1. Capen CC. Endocrine glands. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:326-376.

2. Hatazoe T, Kawaguchi H, Hobo S, Misumi K. Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (equine Cushing?s disease) in a thoroughbred stallion: a single report. J Equine Sci 2015; 26(4):125-128.

3. Leitenbacher J, Herbach N. Age-related qualitative histological and quantitative stereological changes in the equine pituitary. J Comp Path 2016; 154:215-224.

4. Luethy D, Habecker P, Murphy B, Nolen-Walston R. Clinical and pathological featurs of pheochromocytoma in the horse a multi-center retrospective study of 37 cases (2007-2014). J Vt Inten Med 2016; 30:309-313.

5. McFarlane D. Endocrine and metabolic disorders. In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2009:1340-1344.

6. Miller MA, Moore GE, Bertin FR, Kritchevsky JE. What?s new in old horses? Postmortem dignoses in mature and aged equids. Vet Pathol. 2016;53(2):390-398.

7. Rohrbach BW, Stafford JR, Clermont RS, et al. Diagnostic frequency, response to therapy, and long-term prognosis among horses and ponies with pituitary par intermedia dysfunction, 1993?2004. J Vet Intern Med. 2012; 26(4):1027?1034.