Conference 16, Case 1:

Signalment:

15-yr-old pony mare (Equus caballus)

History:

Ten-day history of colic and diarrhea with suspected peritonitis. Tested positive by PCR for equine coronavirus (antemortem), and received aggressive supportive care (IV fluids, antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, etc.), but became persistently painful and was euthanized. The submitting veterinarian was concerned about intestinal infarction or displacement.

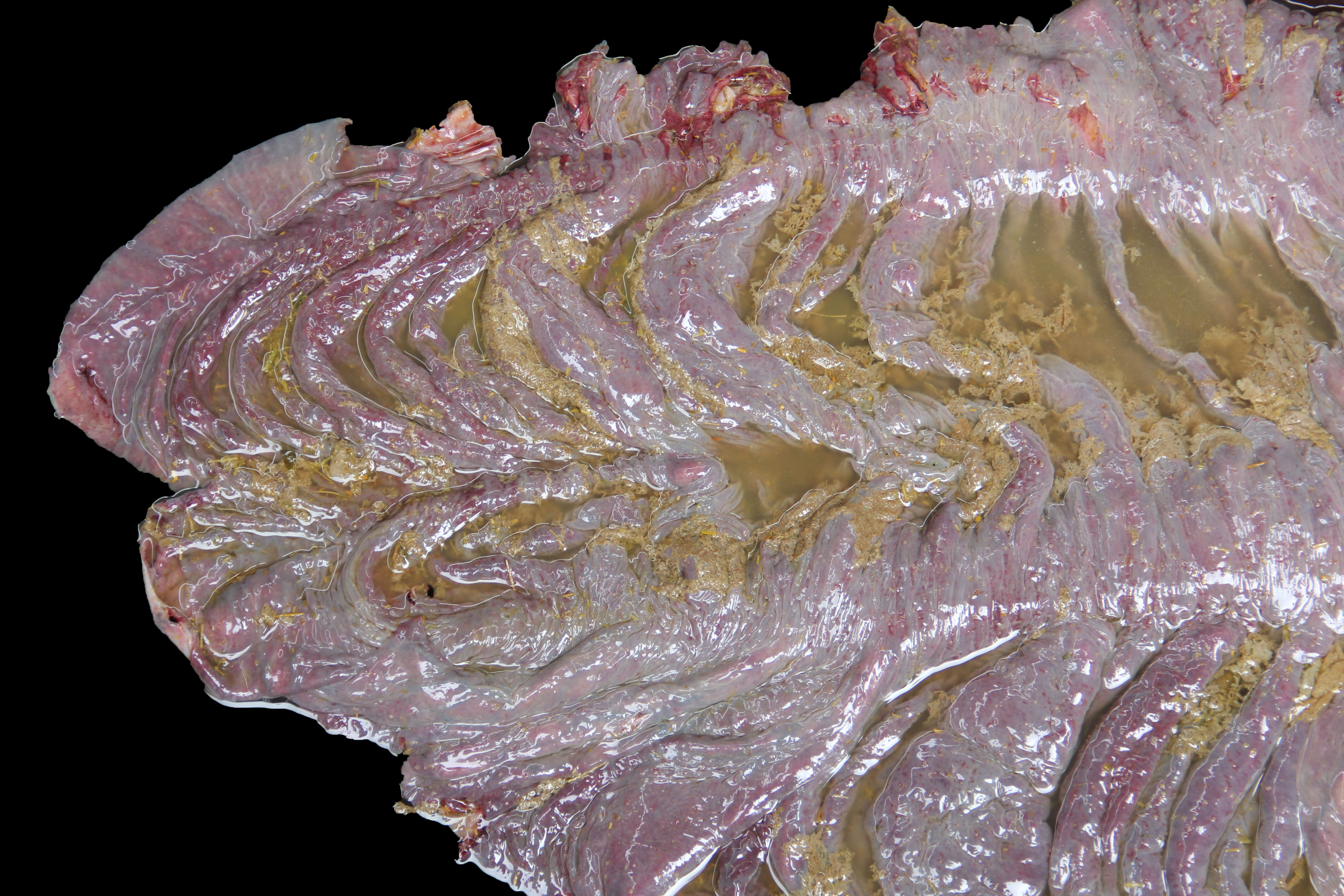

Gross Pathology:

The carcass was in good nutritional condition, with adequate amount of fat reserves, well fleshed, moderately dehydrated, and mild to moderate state of postmortem decomposition.

About 10 liters of murky fluid were present in the abdomen. There were ~ 5 liters of clear thoracic fluid. The serosa of the colon was multifocally hemorrhagic. There was clear liquid content throughout small and large intestine, and a pseudo membrane covering the mucosa of the right ventral colon and cecum.

There was an~ 6 cm diameter jejunal diverticulum with very thick wall, that was adhered to the serosa of the cecum and the parietal peritoneum. The lungs were congested and edematous.

No other significant gross abnormalities were observed in the rest of the carcass.

Laboratory Results:

Clostridioides difficile and Salmonellatyphimurium were isolated from small intestinal and colonic content. S. typhimurium was also isolated from the liver.

ELISA for toxins A and B of C. difficile was positive on small intestinal and colonic contents. ELISA for Clostridium perfringens alpha, beta and epsilon toxins was negative on the same specimens.

Mixed aerobic flora was isolated from small intestinal and colonic contents, liver and lung.

A heavy metal screen on liver revealed that copper and selenium were marginally below normal range. All other heavy metals were within normal range.

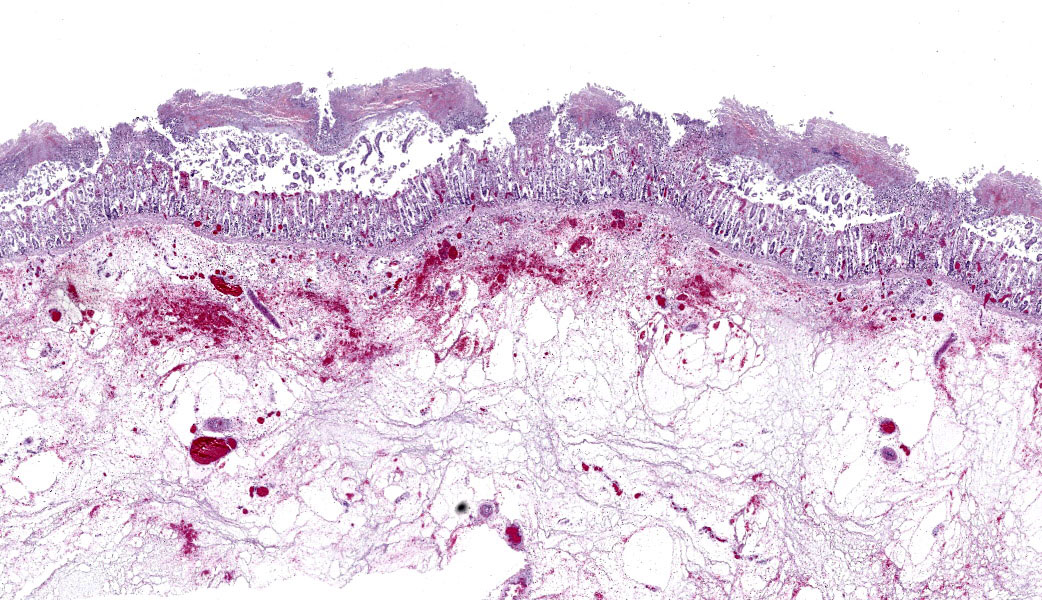

Microscopic Description:

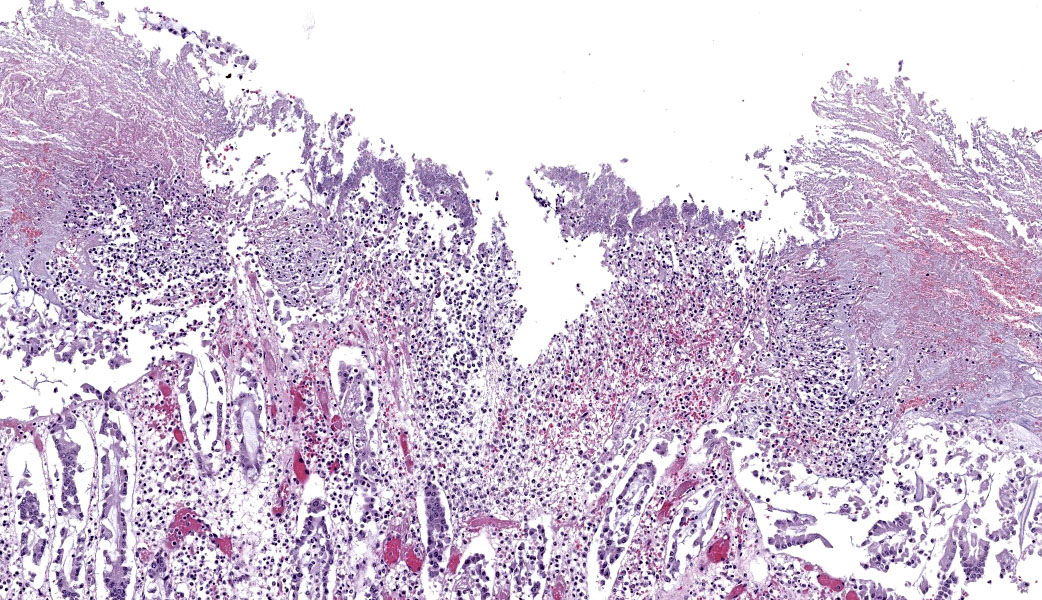

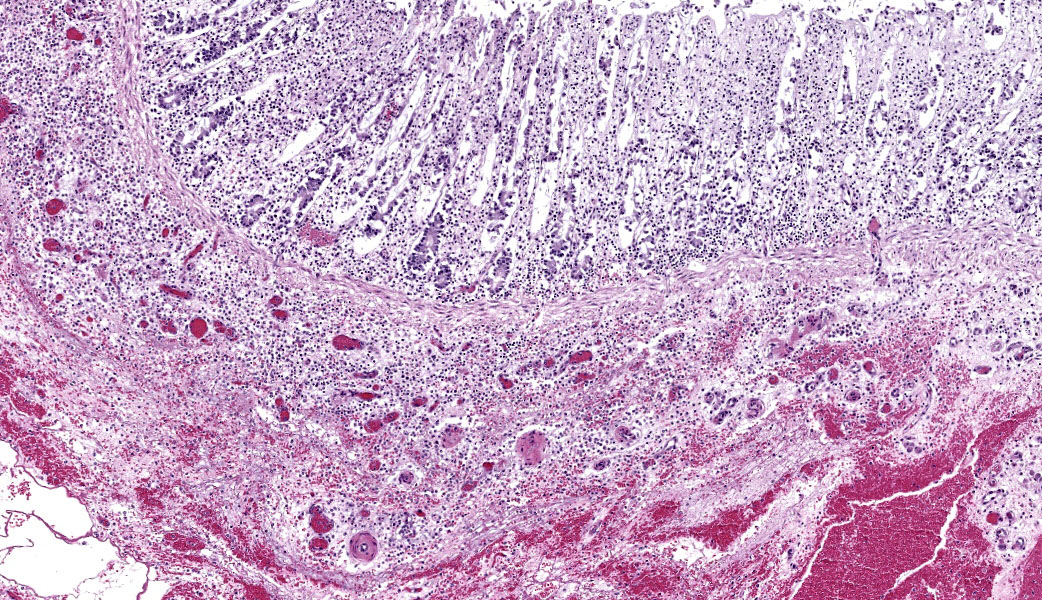

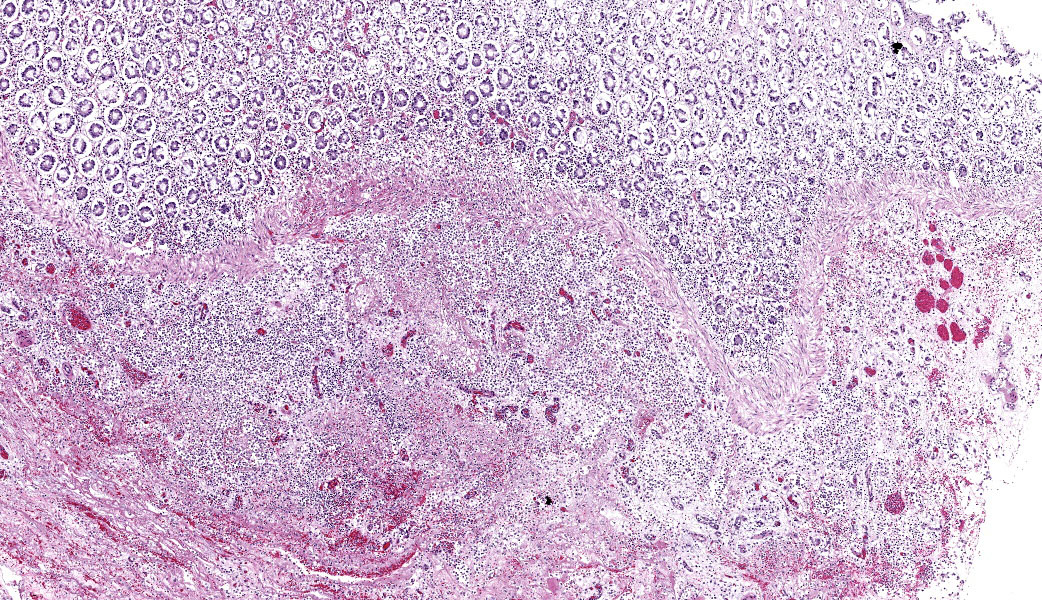

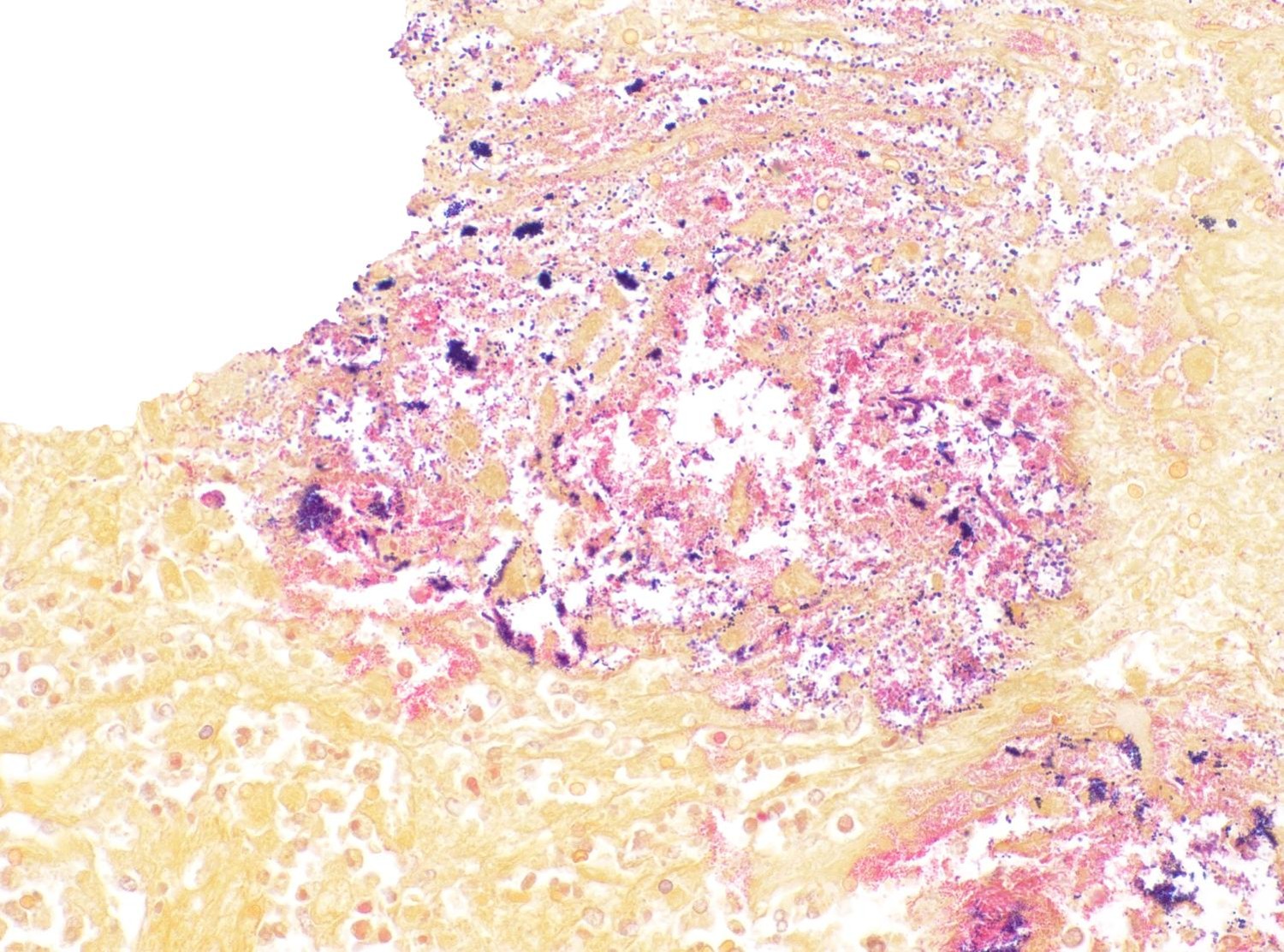

Colon: There is severe, diffuse necrosis of the mucosa where the superficial epithelium and, less prominently, the crypt epithelium is lost and/or show hypereosinophilia, pyknosis, karyorrhexis and karyolysis. The lamina propria is diffusely eosinophilic and infiltrated by a large number of viable and degenerated neutrophils and fewer neutrophils, plasma cells and macrophages; this cellular infiltration extends to the submucosa. Multifocally, the mucosa is covered by a thick pseudo membrane composed of fibrin, cell debris, red blood cells, neutrophils and myriad mixed bacteria. Several blood vessels of the lamina propria show thrombosis. In areas where the superficial epithelium is still present, erosions are seen through which large number of neutrophils are seen exiting the lamina propria into the lumen (volcano lesions). The submucosa is severely dilated and edematous; there is vascular congestion and the lymphatic vessels are dilated. The serosa shows reactive mesothelial cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Colitis, fibrinonecrotizing, diffuse, with thrombosis, volcano lesions, submucosal edema and mixed bacteria

Contributor’s Comment:

This horse had severe colitis produced by a co-infection with C. difficile and Salmonella Typhimurium. Grossly and microscopically, there are several overlapping features in the lesions produced by these two microorganisms which make them impossible to differentiate based only on lesions.3,7 An etiologic diagnosis cannot therefore be made without ancillary laboratory tests.3,7

In the case of S. Typhimurium, the infection was confirmed by PCR and culture followed by serotyping. Detection of this microorganism in intestinal content and liver suggests that the intestinal infection occurred before and there was systemic dissemination through the damaged intestinal mucosa, although intestinal mucosa damage is not a requirement for absorption and dissemination of this Salmonella spp.5,7

The diagnosis of C. difficile infection was confirmed by the detection of toxins A/B of this microorganism in both small and large intestinal content. Because this ELISA test uses a

cocktail of anti-toxin A and anti-toxin B antibodies, the positive result means that in the intestinal content there was one of the two toxins.6 Isolation of C. difficile is suggestive of this microorganism involvement in the colitis, but not confirmatory as a number of clinically healthy horses can harbor C. difficile in the intestine.4,5,6,7 Likewise, both gross and microscopic lesions are suggestive of, but not confirmatory, C. difficile infection. In particular, the volcano lesions are considered highly suggestive for C. difficile infection; this finding should, however, be interpreted with care, as other pathogens can also cause this lesion.3,4,7

The two main predisposing factors for C. difficile infection in horses are antibiotic therapy and hospitalization, both factors that were present in this case.7 It is therefore speculated that salmonellosis occurred first and the attempts to control the disease with hospitalization and antibiotic treatment favored C. difficile infection.

No lesions suggestive of equine coronavirus were observed in the intestine of this horse; in particular, no intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (the hallmark of such infection) were seen.7 However, the necrosis of the mucosa was so extensive that if there were inclusion bodies, these may have been missed. Unfortunately, no post-mortem testing for equine coronavirus was performed.

This horse also had also a small intestine diverticulum, which was considered an incidental finding. Copper and selenium deficiency were also considered incidental findings, although a minor role in infection predisposition cannot be ruled out.

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory, Sa Bernardino Laboratory.

https://cahfs.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/

JPC Diagnoses:

Colon: Colitis, fibrinonecrotic, subacute, diffuse, marked, thrombosis, edema, and volcano lesions.

JPC Comment:

The JPC was thrilled to have the revered Dr. Paco Uzal, who needs no introduction, back again this year as a conference moderator. This first case provided a great example of an equine colitis case with multiple etiologies, something that is common in equine practice. The contributor provided an excellent write-up on this case and touched on many of the primary points of discussion during conference. Some participants struggled with determining if the tissue ID was small intestine or colon due to the degree of necrosis; this is reasonable and it can become incredibly difficult to differentiate the two when the architecture is lost. This horse also had a history of extensive NSAID administration and hospitalization, both of which are predisposing factors for both C. difficile and Salmonella infection. Grossly and histologically, C. difficile, Salmonella spp, and NSAID-induced ulceration can all look identical; culture and toxin typing are necessary for confirmatory diagnosis.3 Participants agreed that the relevance of the previous equine coronavirus infection in this case could not be known.

Salmonella enterica var Typhimurium, thought to be the primary pathogen in this case by both the contributor and conference participants, is a non-host-adapted species of Salmonella that causes enteric disease in numerous species.3 The overt lack of GI-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) histologically should

clue the pathologist in to the possibility for a Salmonella infection due to its tendency to infect the GALT first. Salmonella utilizes a Type 3 secretion system (T3SS) to stimulate phagocytosis and entry into M-cells and, subsequently, macrophages in the underlying lymphoid tissue. Salmonella inhibits fusion of the phagosome and lysosome to ensure its survivability within the macrophage and begins replicating safely within a Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV). From there, it can be trafficked throughout the body hidden within macrophages. Later, using a Type 1 secretion system (T1SS), Salmonella stimulates apoptosis of the macrophage via activation of caspase 1, enabling each Salmonella to escape the host cell and infect additional cells. In this case, Salmonella Typhimurium was cultured from the small intestine, colon, and liver, indicating a septic process.

Clostridioides difficile (renamed in 2016 from Clostridium difficile) affects many species of all ages.1,3 The primary clinical sign is profuse diarrhea. Histologically, “volcano lesions”, as seen in this case, are a hallmark of C. difficile in the acute phase of infection.3,4 Although other organisms (including Salmonella) can cause these lesions, they are considered classic for C. difficile. These lesions are characterized by micro-ulcerations of the mucosa with necrotic debris and neutrophils being “spat out” into the lumen, giving it the appearance of lava spewing from an erupting volcano. Following acute infection, volcano lesions become difficult to see histologically due to the progression to a full-blown necrotizing colitis, the lesions of which are non-specific and can be caused by a number of enteric pathogens (i.e. Salmonella spp, Brachyspira spp, etc.). As mentioned by the contributor, culture is a more suggestive method for confirming a diagnosis of C. difficile, but the results must be interpreted with caution as, according to Dr. Uzal, 3% of clinically normal horses will grow C. difficile on culture of enteric content.4

ELISA testing for C. difficile A/B toxin from the intestinal content/feces of affected animals, which was performed in this case, is considered confirmatory for a diagnosis of C. difficile. These toxins are the primary drivers of disease in C. difficile infection. TcdA (enterotoxin) binds to intestinal brush border receptors, while TcdB (cytotoxin) binds to receptors like LRP1. Both are internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis, where they inactivate small GTP-binding proteins of the Rho/Ras family via mono-O-glucosylation.2 These proteins play key roles in regulating the cytoskeletal dynamics of actin. Their inactivation leads to changes in the shape of the cell, retraction of cell processes, detachment from neighboring cells, and cell rounding.1,2 This causes the cell to undergo apoptosis.1,2 In the case of detachment-mediated stress, this form of apoptosis may be similar to anoikis, a form of apoptosis that occurs in “homeless”, anchor-dependent cells that have become detached from the extracellular matrix and/or surrounding cells.

References:

- Di Bella S, Ascenzi P, Siarakas S, Petrosillo N, di Masi A. Clostridium difficile Toxins A and B: Insights into Pathogenic Properties and Extraintestinal Effects. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8(5):134.

- Liu Z, et al. Structural basis for selective modification of Rho and Ras GTPases by Clostridioides difficile toxin B. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabi4582.

- Mendonça FS, Navarro MA, Uzal FA. The comparative pathology of enterocolitis caused by Clostridium perfringens type C, Clostridioides difficile, Paeniclostridium sordellii, Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in horses. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2021;34:412-420.

- Uzal FA, Diab SS, Blanchard P, Moore J, Anthenill L, Shahriar F, Garcia JP, Songer JG.. Clostridium perfringens type C and Clostridium difficile co-infection in foals. Vet Microbiol. 2012;156:395-340.

- Uzal FA, Diab SS. Gastritis, enteritis, and colitis in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2015;31:337-358.

- Uzal FA, Navarro MA, Asin J, Henderson EE. Clostridial Diseases of Horses: A Review. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:318.

- Uzal FA, Arroyo LG, Navarro MA, Gomez DE, Asín J, Henderson E. Bacterial and viral enterocolitis in horses: a review. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022;34:354-375.