WSC 23-24 Conference 8, Case I

Signalment:

22-year-old, gelding Appaloosa horse (Equus caballus)

History:

This horse had a history of chronic left front foot problems that started after a foot abscess caused by a penetrating foreign body. It had chronic recurrent abscesses with 3 hoof wall resection attempts. A CT scan showed evidence of osteomyelitis and radiographs showed laminitis and a distal displacement abscess in the left front foot. The patient also had a history of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma in the penile sheath and a new lesion in the left third eyelid. The patient also had unregulated pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. The patient started dribbling urine and the clinician was concerned about renal, lower urinary tract, or neurologic disease. Humane euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

At necropsy, mucosal membranes were congested. The cranial margin of the left third eyelid contained a 3 mm focal raised, pink nodule. The skin at the base of the penis had multifocal to coalescing 4 to 13 cm raised plaques covered by yellow, friable, crusty material. Urine was oozing freely from the urethra. Multiple 1 to 4 cm diameter black

nodules were disseminated within the subcutis of the neck and adjacent to the esophagus. One 1 cm diameter round ulcer was present at the base of the tongue. Petechiae and ecchymoses were observed on the pericardium. The spleen was enlarged, meaty, and oozed blood. There was a round 3 cm white, soft mass attached to the mesentery, interpreted as lipoma. The liver and kidneys were diffusely congested. The urinary bladder was filled with moderate amounts of opaque yellow urine and the urinary bladder wall was moderately thick and diffusely red. The rest of the urinary tract was unremarkable with no obstructions or uroliths present. Each hoof had variable degrees of fragmentation of the external corneal layer with cracks, with the left

front hoof being the most severely affected. On section, the left frontal third phalange had severe deviation of the cranial margin with signs of laminitis and the hoof wall was markedly thickened and contained an air pocket. The pituitary gland was slightly bulged. Representative sections of observed lesions were collected for histopathology.

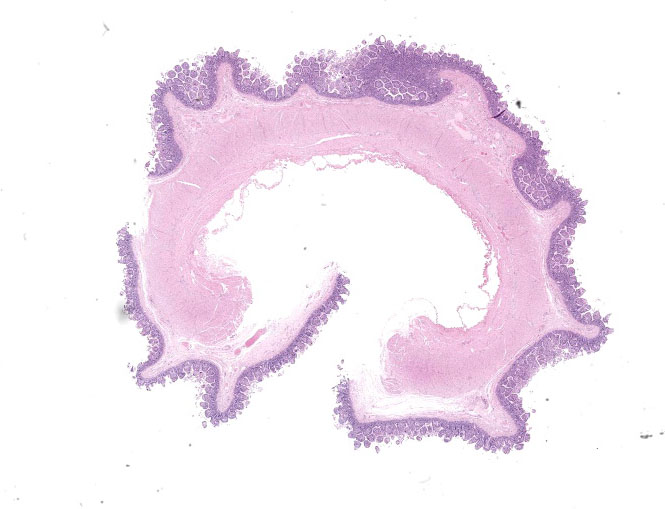

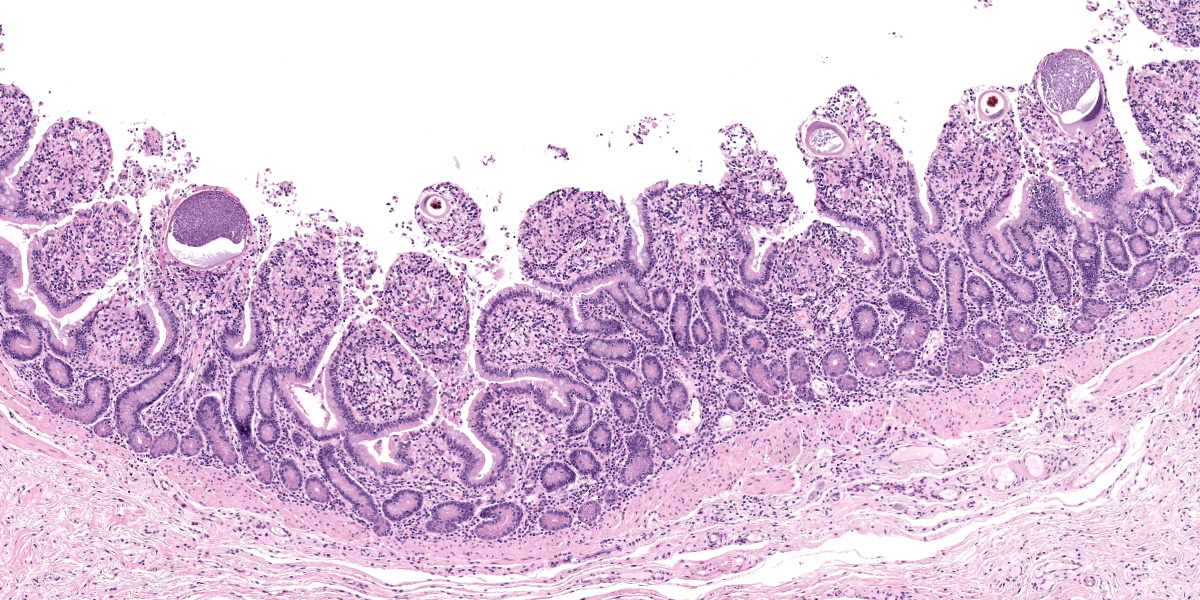

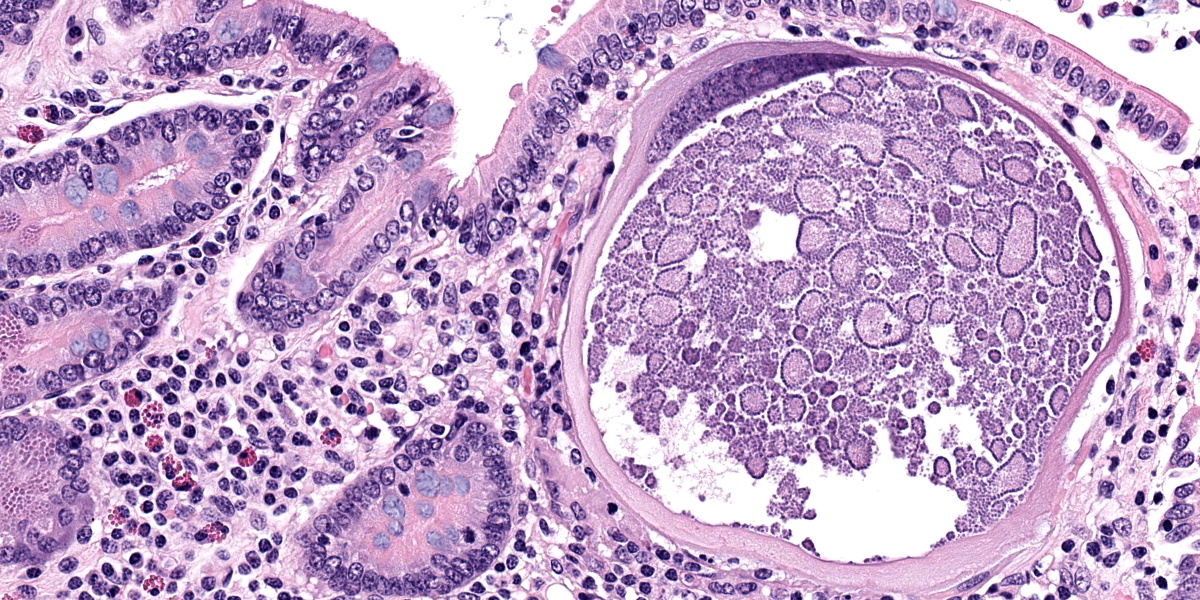

Microscopic Description:

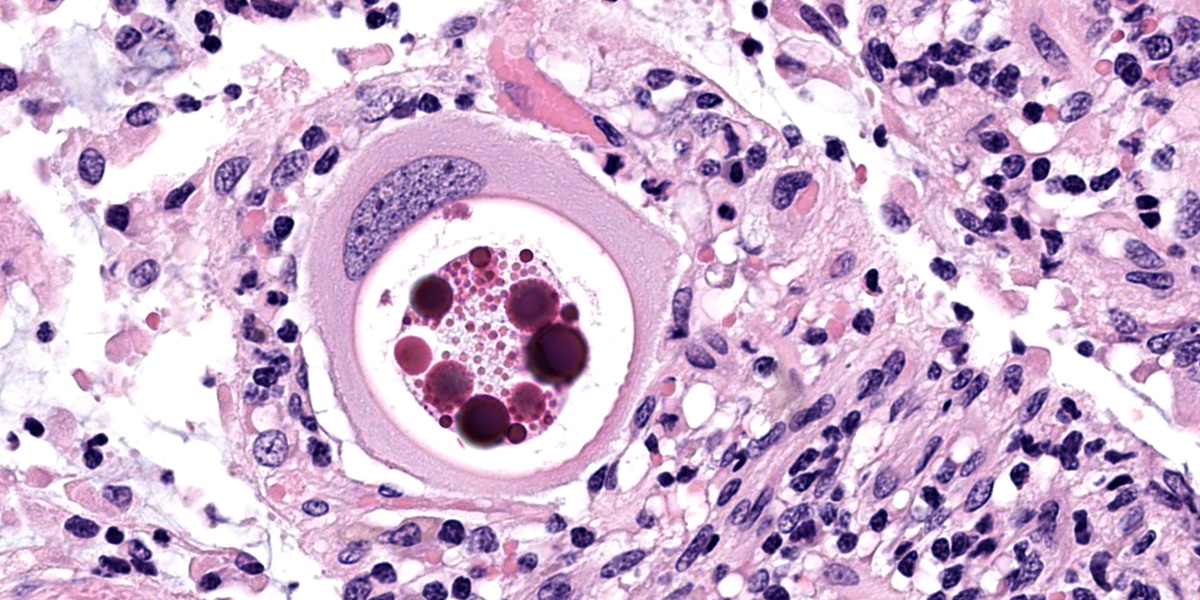

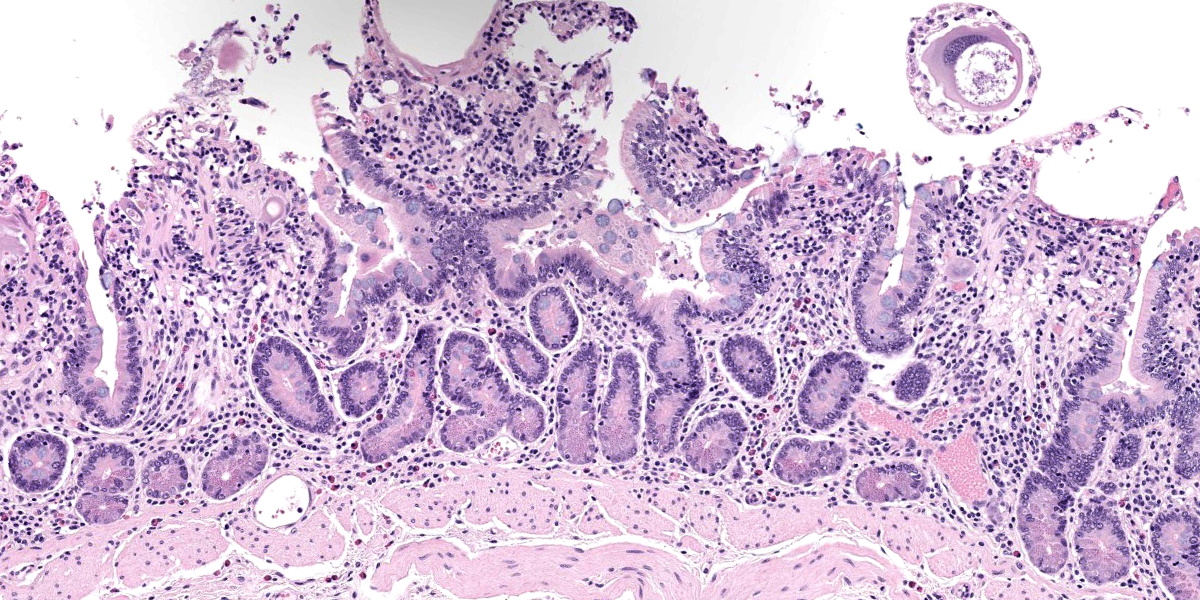

Small intestine: Most villi are atrophic and blunted. The lamina propria is mildly to moderately expanded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. A few eosinophils are observed within the submucosa. Within the lamina propria multiple host cells are markedly hypertrophied up to 30-250 µm in diameter with fibrillar cytoplasm and an enlarged peripheral nucleus that forms a crescent along one side of a thick eosinophilic parasitophorous vacuole. The parasitophorous vacuole contains various stages of development of Eimeria leuckarti, including microgamonts, macrogamonts, and occasional developing oocysts. Mature microgamonts contain myriad 1-2 µm basophilic microgametes. Intimal bodies are observed in small arteries and arterioles of the submucosa.

Other additional microscopy findings in this horse included pars intermedia pituitary adenoma, squamous cell carcinoma (prepuce and third eyelid), melanomas (neck), osteomyelitis (left front foot), chronic lymphoplasmacytic cystitis, multifocal mineralization of the brain (incidental finding), and eosinophilic preputial dermatitis of unknown etiology (habronemiasis suspected).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Enteritis, eosinophilic and lymphoplasmacytic, mild, subacute with intralesional coccidia (consistent with Eimeria leuckarti).

Contributor’s Comment:

This horse was in declining health with multiple clinical problems that culminated in humane euthanasia. The intestinal coccidiosis was considered an incidental finding in this horse.

More than a thousand species of Eimeria are known to infect domestic and wild animals and birds.5Eimeria leuckarti is the only species of Eimeria consistently reported in horses and it has been consistently found worldwide.3,10 Infection with E. leuckarti is more common in foals but it also affects adult horses.3,10 Most infections are considered to be of no clinical relevance.3,10 Clinical enteritis has been reported in very few cases.3 E. leuckarti was named after the German scientist Rudolf Leukart and was first recognized as a large-sized protozoan in sections of small intestine of a horse used for teaching anatomy in Switzerland. E. Leuckarti has been found in several species of equids including horse, donkey, mule, Asian wild ass, Mountain zebra, and Grant’s zebra.3

In a study of parasites of horses in farms in Kentucky, E. leuckarti infection was common in foals as young as 28 days of age.7 Prevalence of E. leuckarti oocysts in feces of foals in Kentucky from studies in 1986 and 2003 were similar at 41% and 41.6%, respectively, with E. leuckarti found in 100% of the farms in the 2003 study and 86% of farms in the 1986 study.7,8 Foals can acquire the infection on the day of birth, most likely from the contaminated environment rather than from oocysts excreted by their mares.3 In another study, the prevalence of foals affected by E. leuckarti was 59%.9

The life cycle for each species of Eimeria is host specific and direct.5 Sexual stages identified as macrogametes (female) are uninucleate and contain peripheral PAS-positive granules. The immature male stage (microgamont, microgametocyte) is multinucleated. When each nucleus becomes incorporated into a sperm-like biflagellate structure (microgamete), the microgamont is considered mature.5 So far, only gamonts and oocysts of E. leuckarti have been found in histological sections of small intestine; asexual stages of E. leuckarti have not yet been confirmed.3

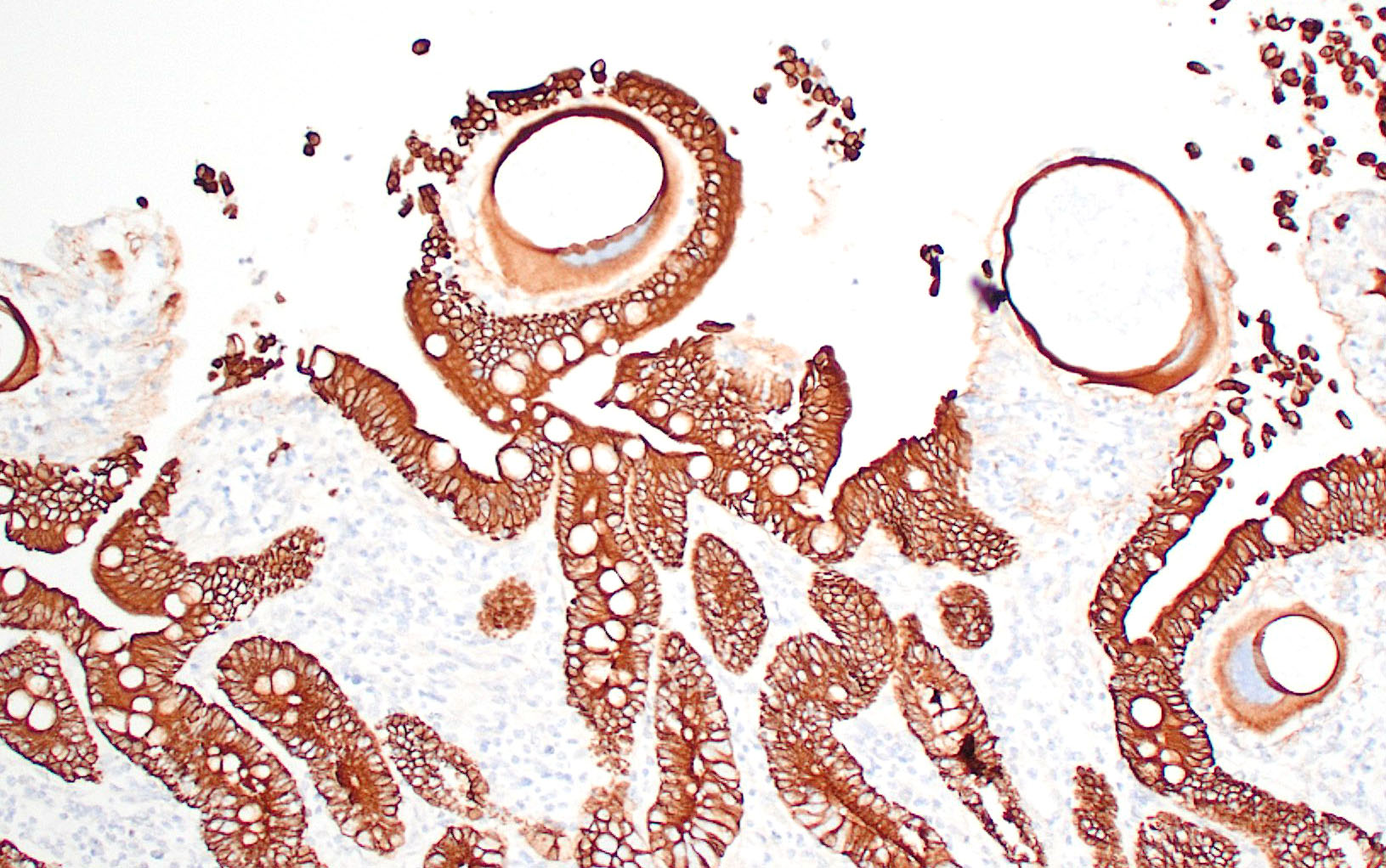

E. leuckarti develops in the cytoplasm of hypertrophied host cells in the lamina propria of the small intestine.3,5,6 An immunohistochemical study identified these cells as epithelial cells.6 In this study, the cytoplasm of the host cells was immunopositive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and cytokeratin 13. Host cells did not react to vimentin, chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, desmin, alpha smooth muscle actin, or factor VIII. It was hypothesized that laminin may regulate the displacement of epithelial host cells parasitized by E. leuckarti into the lamina propria.6 In addition, the expression of CK13 by the host cells implied that the lifespan of the host cells was possibly extended. How the host cells were dislocated to the lamina propria and achieved the extended life span was unclear.6

Usually there is no host inflammatory response to E. leuckarti and only a mild reaction to degenerate life stages can be seen.3,10 Parasites are found in the lamina propria towards the luminal part of the villus but some occur throughout villi.3 In most reports, infections with E. leuckarti in equids were considered incidental; however, occasionally it has been considered a cause or contributing factor to enteritis in foals.3 In many cases, its pathogenicity is attributed to the distinctive large gamonts observed in the lamina propria of horses that died of enteric disease of undetermined cause, however the evidence for E. leuckarti causing enteric disease is rarely conclusive.10

Detection of E. leuckarti oocysts in feces is confirmatory for diagnosis; however, oocysts may be overlooked during routine fecal analysis that uses standard, low specific gravity floatation technique due to the large size and the heavy weight of oocysts.3,9 The use of a sedimentation technique or floatation method using solution with a specific gravity of 1.3 or higher is recommended because E. leuckarti oocysts are large and heavy.3,9 Saturated sodium chloride solution is not recommended.3 Adding to the difficulty in diagnosing E. leuckarti is the short duration of patency and the relatively low oocyst output.9

In histological sections, the presence of gamonts and oocysts in the lamina propria of the jejunum and ileum is diagnostic.3,10 There is a need for case-controlled studies to better understand the pathogenicity of E. leuckarti in equids.3

Contributing Institution:

Tifton Veterinary Diagnostic and Investigational Laboratory

College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Georgia

43 Brighton Road, Tifton GA 31793.

https://vet.uga.edu/diagnostic-service-labs/veterinary-diagnostic-laboratory/

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Enteritis, lymphoplasma-cytic and eosinophilic, diffuse, mild, with marked villar atrophy and numerous intraepithelial coccidia consistent with Eimeria leuckarti.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor notes, Eimeria leukarti is a common parasite of the equine gastrointestinal tract; however, despite its ubiquity, it rarely causes significant disease and is most often encountered, as in this case, as an incidental finding at necropsy.

Eimeria spp. are not, however, universally benign. In sheep, Eimeria gilruthi forms megaloschizonts in the abomasal mucosa that are visible to the naked eye as multiple white, raised foci, and the clinical disease may include diarrhea, dehydration, anorexia, and weight loss.1,4 In rabbits, Eimeria stiedae develops in the biliary epithelium of bile ducts and can cause significant hepatic changes, visible as large white foci on the surface of the liver, that often culminate in death.4

Eimeria spp. are coccidians, which are single-celled obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa. They keep phylogenetic company with other coccidian genera of veterinary importance, including Klossiella, Cystoisospora, Hammondia, Besnoitia, Sarcocystis, Neospora, and Toxoplasma, all of which cause disease by destroying their host cells.2,4

Eimeria spp. exhibit the simplest form of the coccidian life cycle, which includes both asexual and sexual stages in the gastrointestinal tract of many vertebrate hosts.2 Sexual reproduction produces oocysts which are released into the environment by rupture of host gastrointestinal epithelial cells and subsequent passage in the feces. Once in the environment, Eimeria oocysts develop eight infective sporozoites through the process of sporulation.2

Once the infective sporulated oocyst is ingested by a suitable host, the sporozoites emerge and enter epithelial cells or cells of the lamina propria, where they round up and become trophozoites in a membrane-bound parasitophorous vacuole formed by the host cell membrane.2 The trophozoites grow larger and multiply asexually within host cells via schizogony (also known as merogony), in which the apical complex is replicated, the nucleus lobulates with portions associated with each apical complex, and the cell membrane contracts and divides to form many individual merozoites encased in a schizont.4 Depending on the Eimeria spp., there may be multiple generations of schizont and merozoite formation; however, the key outcome of schizogony is an exponential increase in the number of zoites and the destruction of host cells in proportion to the degree of infection.2

Merozoites produced by the final round of schizogony enter host cells and develop into either microgamonts (male) or macrogamonts (female) through the process of gametogony.2 Microgamonts undergo repeated nuclear divisions with each nucleus finally incorporated into a flagellated microgamete, which fertilizes the macrogamete to form a zygote.4 Eosinophilic globular wall-forming bodies present in the macrogamete then coalesce to form a wall around the zygote, forming an oocyst.2,4 This oocyst is released by rupture of the host cell and the cycle begins anew. This basic life cycle pertains, albeit with increasing complexity and nuance, to the other coccidian genera of veterinary importance.

Our moderator for parasite week was Dr. Chris Gardiner, PhD, self-proclaimed “parasitologist to the stars”. Discussion of the parasite in this case focused on identifying the various life stages in tissue section. Several conference participants identified organisms in section as oocysts, though Dr. Gardiner thought they represented trophozoites, the gamont precursor. We noted that the contributor also described oocysts, but none were present in the examined section.

The discussion of pathologic changes centered on the villi, which are substantially blunted, and the degree of inflammation present in the lamina propria. Dr. Bruce Williams noted that intestinal crypts should be closely apposed and should rest on the muscularis mucosae; however, in this case, crypts were widely and irregularly separated and were multifocally elevated off the underlying muscularis mucosae. Though the lamina propria normally hosts a substantial population of inflammatory cells, these crypt changes are important clues that the inflammation (and edema) is more florid than normal, even when, as in this case, the enteritis is considered mild.

References:

- Ammar SI, Watson AM, Craig LE, et al. Eimeria gilruthi-associated abomasitis in a group of ewes. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019;31(1):128-132.

- Bowman DD. Protozoa. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th ed. Elsevier;2009:92-94.

- Dubey JP, Bauer C. A review of Eimeria infections in horses and other equids. Vet Parasitol. 2018;256:58-70.

- Eberhard, ML. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th ed. Elsevier;2009:377-380.

- Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP. An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. 2nd ed. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology;1998;20-28.

- Hirayama K, Okamoto M, Sako T, et al. Eimeria organisms develop in the epithelial cells of the equine small intestine. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:505-508.

- Lyons ET, Drudge JH, Tolliver SC. Natural infection with Eimeria leuckarti: Prevalence of oocysts in feces of horse foals on several farms in Kentucky during 1986. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:96-98.

- Lyons ET, Tolliver SC. Prevalence of parasite eggs (Strongyloides westeri, Parascaris equorum, and strongyles) and oocysts (Eimeria leuckarti) in the feces of Thoroughbred foals on 14 farms in central Kentucky in 2003. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:400-404.

- McQueary CA, David EW, Catlin JE. Observations on the life cycle and prevalence of Eimeria leuckarti in horses in Montana. Am J Vet Res. 1977;38:1673-1674.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb,Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier;2016:233.