Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 13

8 January 2020

CASE II: HSRL-425 CVM-WU-2 (JPC 4038890).

Signalment: 3-year-old intact male feral domestic short hair cat (Felis catus)

History: An approximately 3-year-old 4.5 kg intact male feral, DSH (Felis catus) was presented to a veterinary hospital in Pomona, California. A good Samaritan used a live trap to capture the animal after she noticed excessive swelling in the nasal region. She was bitten during the capture process. The swelling was localized over the bridge of the nose and had a 3 cm ulcerated area that was bleeding excessively. Due to financial constraints and prognosis, the cat was euthanized and submitted for necropsy and rabies testing.

Upon initial examination, there was gross swelling at the bridge of the nose, and the eyes were nearly shut due to the severe conjunctivitis with abundant secretion. Dorsal to the nasal planum, there was an ulcerated area about ~3cm in diameter that had missing skin, covered by partially clotted blood mixed with necrotic debris.

Gross Pathology: The cat was in thin body condition with a large (3cm in diameter) ulcerated area on a severely swollen space-occupying lesion on the bridge of the nose. No gross abnormalities were found upon examination of internal organs. The cat was underweight and was ~10% dehydrated. A nasal swab was performed and stained with Diff Quik. Fungal organisms were visualized; however, narrow or broad based budding could not be identified. A tentative diagnosis of cryptococcosis was given.

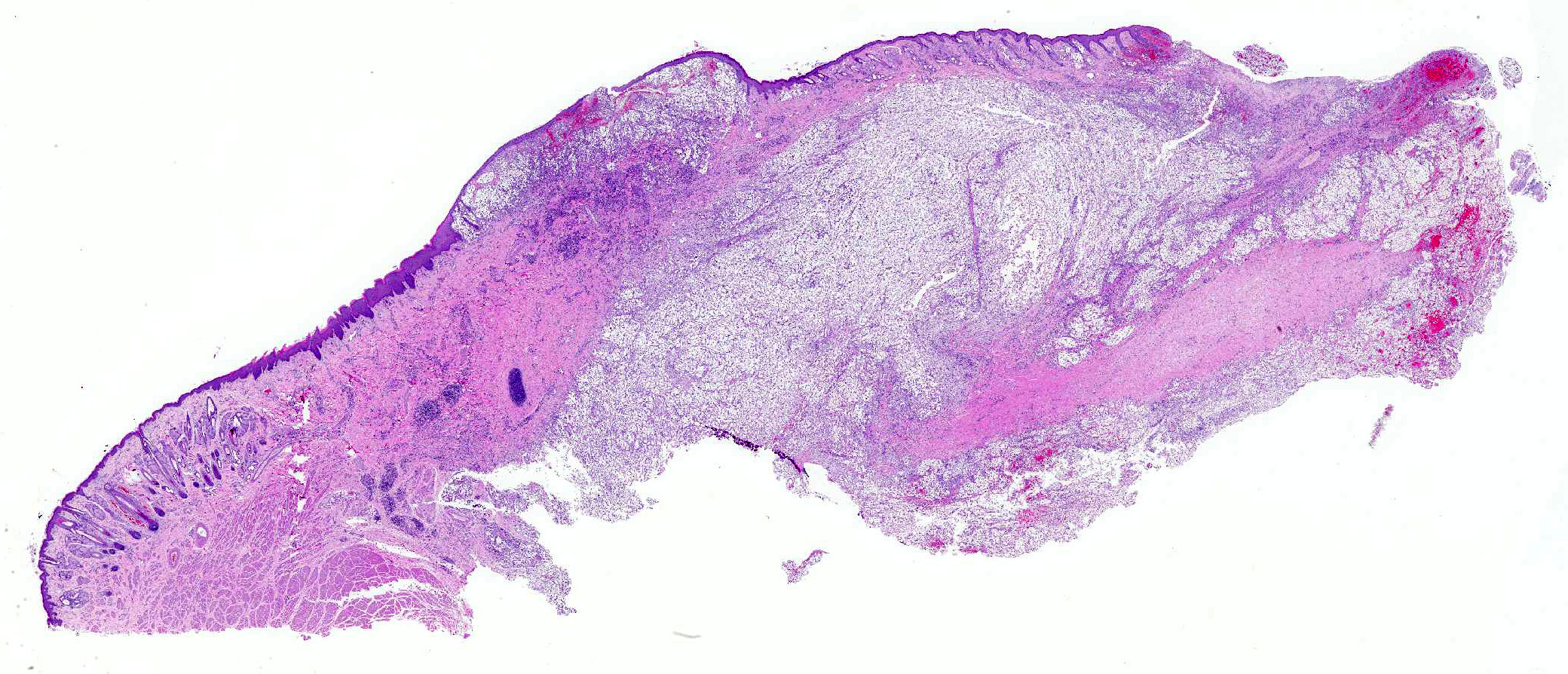

Nasal planum has a large bulging mass (5cm in diameter) that expands and deforms the dorsal planum. The bulging mass has a superficial 3cm in diameter ulceration that connects with the nasal cavity. The ulcer is covered by partially clotted blood mixed with necrotic debris. The philtrum is intact. On cut section the mass is solid and occupies the nasal cavity replacing the turbinates and sinuses.

Laboratory results:

The brain was submitted in toto for rabies testing. Rabies testing was negative.

Microscopic Description:

Tissues submitted for histopathology included lung, liver, kidney, eye and portions of the nasal mass.

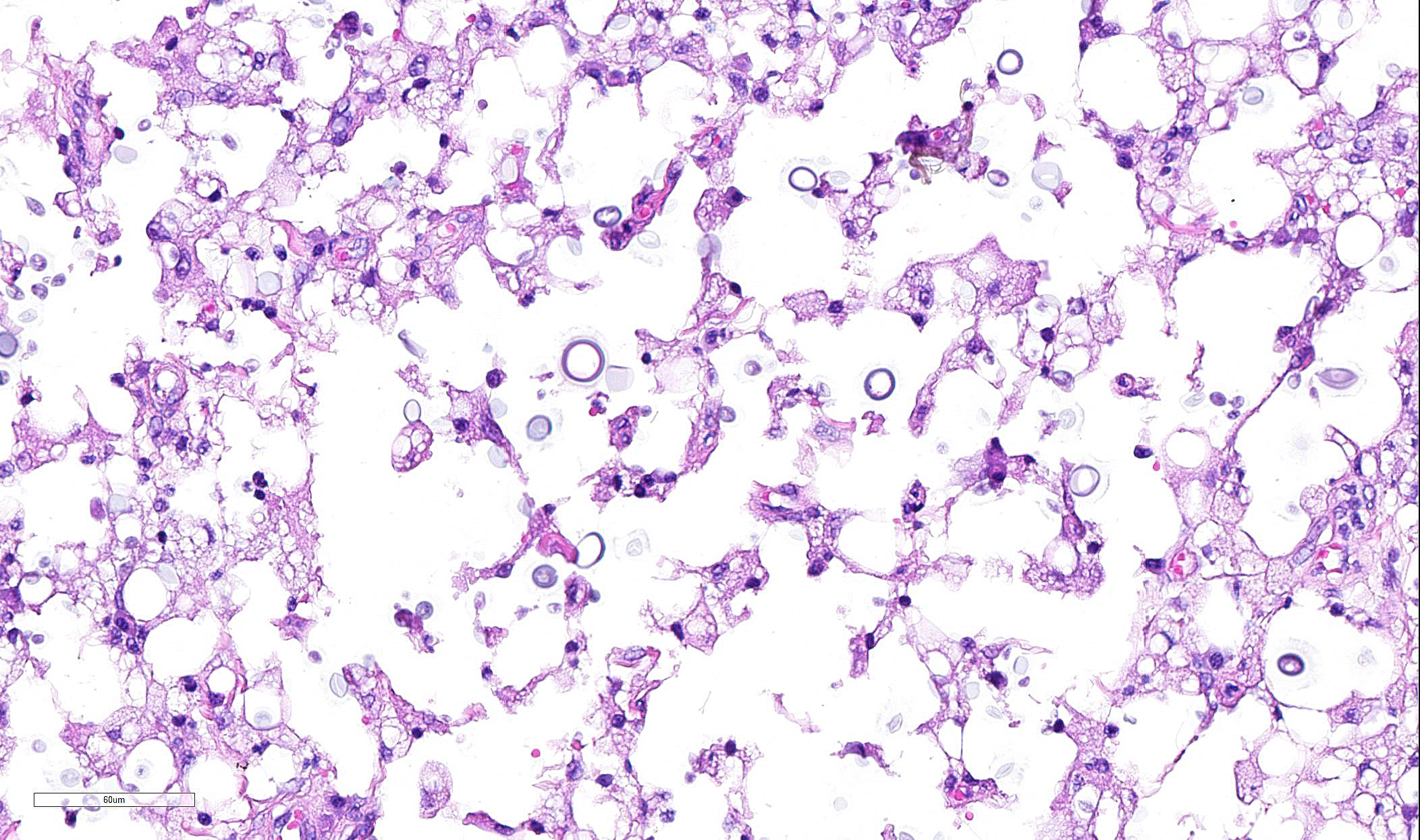

Skin from nasal area (from mucosa to haired skin): There is a locally extensive inflammatory area that extends to the deep limits of the examined sample. The submucosa is severely distorted and replaced by numerous round yeasts admixed with histiocytes, occasional multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells. The yeasts vary from round with a thick wall to oval slightly pink transparent cells. These cells vary from 5-25 µm in diameter. The blastoconidia (asexual reproduction) is characterized by narrow based budding. The yeasts have a clear, thick capsule that gives the characteristic empty space around the yeast. The overlying epithelium is variably ulcerated with occasional acanthosis.

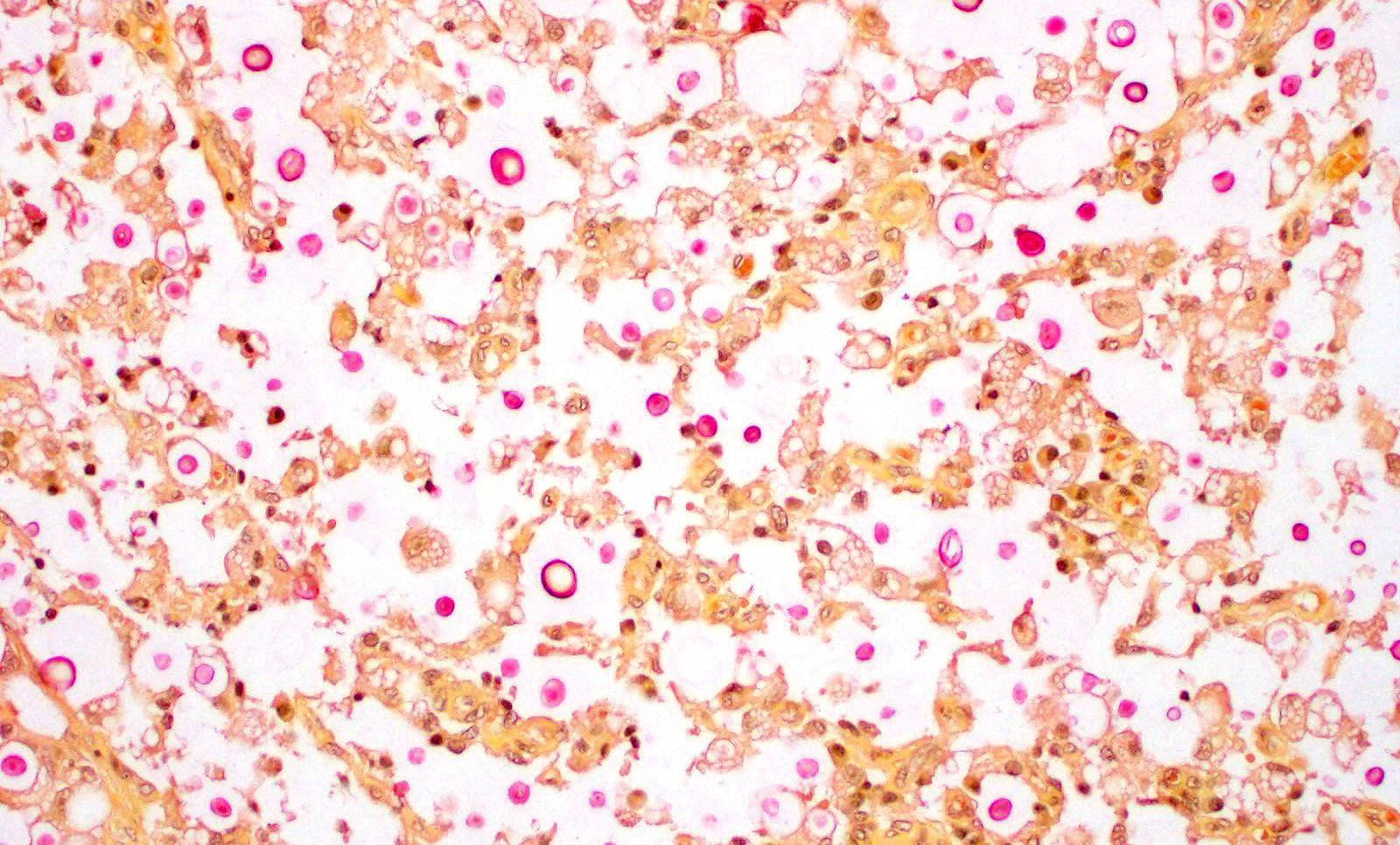

Nasal sections stained with PAS stain in addition to routine H&E staining show characteristic fungal organisms.

The eye was examined. There is severe suppurative inflammatory conjunctivitis with no fungal organism observed.

The other tissues show no significant changes.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Morphologic Diagnosis: Nasal planum: Chronic, locally extensive, severe granulomatous rhinitis with superficial focal dermal ulceration and hemorrhage

Contributor Comment: Cryptococcus is an important dimorphic, basidiomycetous encapsulated fungal organism causing disease in humans and animals.3,5 Cats seem to be the most susceptible species.3,5

It is an encapsulated fungus that replicates by narrow based budding (blastoconidia -asexual reproduction also called vegetative stage). The organism has also a sexual stage of reproduction called basidiospores rarely found in the natural cases. The infection occurs by environmental exposure and is not thought to be transmissible from one infected animal to another. The main environmental source is bird excreta, mainly pigeons.3,5,12

Cryptococcus are aerobic, non-fermentative organisms that form mucoid colonies on a variety of media. Virulence factors utilized by the yeast include its polysaccharide capsule, melanin, mannitol, and enzymes such as phospholipase, laccase and superoxide dismutase. Phopholipase and laccase are unique to C. neoformans and C. gatti and are thought to increase pathogenicity by interfering with the host immune response. The severity of the disease is the result of the combination of the virulence factors coupled with the immune status of the patient.1,3,12

The thick polysaccharide capsule interferes with the protective immune reaction against the yeast preventing successful phagocytic. There is some evidence to correlate the immune status of the patient to the inflammatory response against the organism. The most susceptible patients have T-cell deficiencies. In cats there is no breed or gender predisposition. Cats younger than 6 years appeared to be at higher risk. Retroviral infection in cats is not considered a risk factor. The most common presentations in cats include upper respiratory (like in this case), cutaneous, or central nervous system.1,3,5,10,11

There are about 40 different species within the genus of Cryptococcus. C. neoformans is the only pathogenic species. There are 4 species of Cryptococcus neoformans recognized which are separated in 4 different serotypes (A-D). The different types have different geographic distribution as well as virulence. C. gatti is considered being the most pathogenic.5,9 C. gatti (Cg) has been identified as an emerging infectious disease that not only affects immunosuppressed patients but also those with a intact immune response.1,2,3,5,6.

The lesions caused by Cryptococcus spp are composed of exclusively fungal organisms and minimal inflammatory response. The inflammatory reaction and fungal morphology is very characteristic however the differential diagnosis regarding the organisms includes coccidiodomycosis, Candida, and Histoplasma.1,3,5,7 Histopathology, supported by silver stains (Gomori methenamine silver ? GMS) or polysaccharide stains (periodic acid- Schiff - PAS) is the fastest and cost effective means of achieving a diagnosis when fungi are suspected. The diagnosis is made by the identification of the typical encapsulated yeast in cytology or histopathology. Its polysaccharide capsule positive to mucicarmine and Alcian blue stain is characteristic. The cerebrospinal fluid of affected patients can be stained with India ink to identify the organism. However alternative molecular diagnostic tests have been developed to achieve a definite diagnosis, including serum cryptococcal antigen that is thought to be the best way to reach a definitive diagnosis. Molecular diagnostic test are also available including PCR, amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST).9

Contributing Institution:

College of Veterinary Medicine

Western University of Health Sciences

http://www.westernu.edu/xp/edu/veterinary/about.xml

JPC Diagnosis: Mucocutaneous junction, nose: Dermatitis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe with numerous intra- and extracellular yeasts.

JPC Comment: In 1894, Cryptococcus neoformans was simultaneously identified as a human and juice pathogen by pathologist Otto Busse (from a granulomatous lesion in the tibia of a 31-year-old woman), and Italian scientist Francesco Sanfelipe (from peach juice). The true pathogenic nature of C. neoformans, however, was not realized until the 1980?s when immunosuppressed AIDS patients provided appropriate venue for its pathogenic abilities and a tragic opportunity for widespread research.7

The basics of Cryptococcus infection are well known, and reviewed by the contributor above. In the last decade, a number of new insights have been gained into the pathogenic mechanisms of cryptococcal infection.

Size in important in many phases of cryptococcal infection. Infection is most likely the result of inhalation, but not of the yeasts of the size seen in this case (6-15um) which are too large for inhalation into the deeper airways of the lung (usually 5um or less). Infection more likely occurs from desiccated cells or spores, which set the stage for latent infection which is stimulated to growth by immunosuppression later in life.8

Another instance in which yeast size impacts pathogenesis is the formation of atypical yeast forms which helps cryptococcus in establishing latent infection or perpetuating its disease-causing growth phase. Unusually small forms, known as metabollically inactive "drop" or "micro" cells measure 2-4um and possess a thickened cell wall, making them attractive for phagocytosis by macrophages and likely important in latent infection.8 Another atypical form resides at the opposite pole of the size spectrum - "titan" cells, polyploid cells which exceed 12um in diameter. These cells have a highly crosslinked resistant capsule and also a thickened cell wall with chitin to assist in phagocytosis evasion. The production of host chitinases need to break down these forms appears to be detrimental to the overall inflammatory response.8

Two distinct pathogeneic species, Two distinct species, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptcoccus gatti exist within the genus since 2000. They differ in host requirements, with C. neoformans (and its subspecies C. neoformans var. grubii) causing disease in immunosuppressed hosts, and C. gatti infecting immunocompetent animals. One of the commonly infected animals in Australia, unfortunately, is the koala, which lives among species of eucalyptus trees which naturally host the sexual phase of the fungus.4 In some parts of Australia, especially on the eastern coast, colonization rates of of 94-100% occur in koalas, and may act as a reservoir and amplifying host. Affected koalas present with pneumonia and miningoencephalitis, but many koalas possess subclinical infections which provide a resource for studying latent infection.4

One of the attendees from the National Zoo mentioned that animals that had been treated long term with antifungal agents may have grealy reduced to absent capsules, and that additionally, this fungus may be pigmented. Cryptococcus also has an organelle known as a microsome, which allows it to metabolize xanthine and urates, which facilitates its survival in bird feces.

References:

1 Buchanan, K. L., & Murphy, J. W. (1998). What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen?. Emerging infectious diseases, 4(1), 71.

2. Castrodale L. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging infectious disease of the Pacific

Northwest. State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin. September 1, 2010,

no. 27. http://www.epi.alaska.gov/bulletins/docs/b2010_27.pdf

3. Chandler FW and Watts JC. Pathologic Diagnosis of Fungal

Infections. ASCP Press Chicago USA 1987 p161-175.

4. Chen SCA, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gatti

infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014 27(4):980-1024.

5. Guarner, J., & Brandt, M. E.

(2011). Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clinical

microbiology reviews, 24(2), 247-280.

6. Krockenberger, M. B., & Lester, S. J. (2011).

Cryptococcosis?Clinical Advice on an Emerging Global Concern. Journal of

feline medicine and surgery, 13(3), 158-160.

7. Lamm, Catherine G., Sterrett C. Grune, Marko M. Estrada,

Mary B. McIlwain, and Christian M. Leutenegger. "Granulomatous rhinitis

due to Candida parapsilosis in a cat." Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic

Investigation (2013).

8. May RC, Stone NRH, Wiesner DL, Bicanic T, Nielsen K.

Cyrptococcus: from environmental saprophyte toblobal pathogen. Nat Rev

Microbiol 2016; 14(2):106-117.

9. Sidrim, J. J. C., Costa, A. K. F.,

Cordeiro, R. A., Brilhante, R. S. N., Moura, F. E. A., Castelo-Branco, D. S. C.

M. & Rocha, M. F. G. (2010). Molecular methods for the diagnosis and

characterization of Cryptococcus: a review. Canadian journal of microbiology,

56(6), 445-458.

10. Simmer M, Secko, D. A Peach of a Pathogen: Cryptococcus Neoformans

The Science Creative Quarterly. August 2003. Accessed July

2013. http://www.scq.ubc.ca/a-peach-of-a-pathogen-cryptococcus-neoformans/

11. Sykes, J. E., B. K. Sturges, M. S. Cannon, B. Gericota,

R. J. Higgins, S. R. Trivedi, P. J. Dickinson, K. M. Vernau, W. Meyer, and E.

R. Wisner. "Clinical signs, imaging features, neuropathology, and outcome

in cats and dogs with central nervous system cryptococcosis from

California." Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 24, no. 6

(2010): 1427-1438.

12. Trivedi, Sameer R., Richard Malik, Wieland Meyer, and Jane E. Sykes. "Feline cryptococcosis: impact of current research on clinical management." Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery 13, no. 3 (2011): 163-172.