Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 21

24 March 2019

CASE III PA 38/15 (JPC 4085106)

Signalment: Italian Romagnola Duck (Roman Duck), Anser anser

History: Multiple animals in the flock started dying suddenly without apparent cause or change in the management. The mortality is associated with a marked drop of egg deposition.

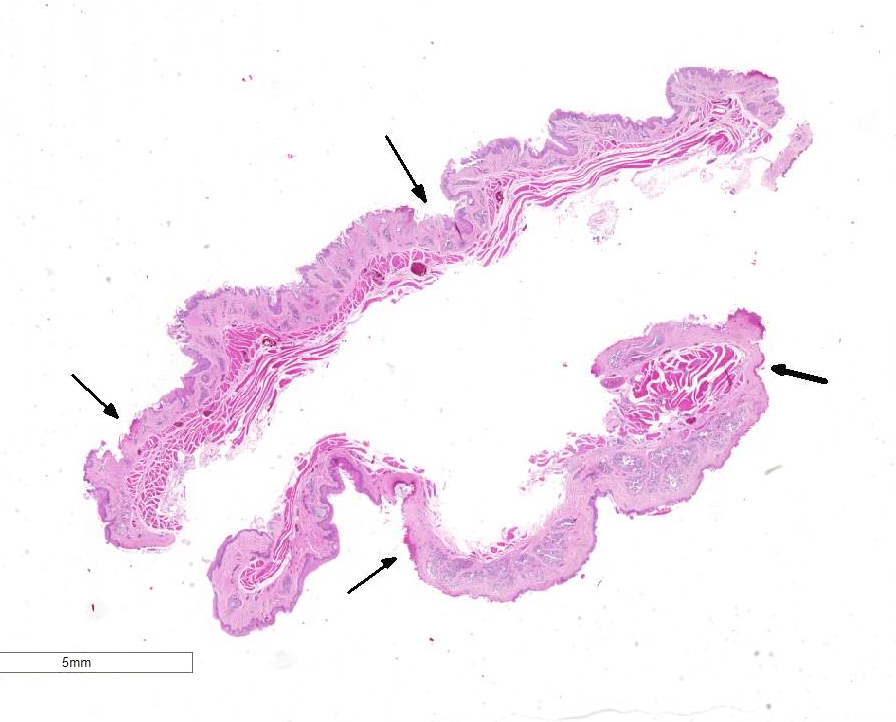

Gross Pathology: The breeder submitted only one spontaneously dead subject. The animal was a female in good postmortem and body conditions. Abundant mucous material diffusely covered the esophagus of the duck. In the proximal esophagus, beneath the mucous, multiple, multifocal to confluent, round to oval, 2 to 4mm in diameter, plaque lesions with tan-yellow discoloration and tightly attached to the mucosal surface are present. No other lesions were noted macroscopically.

Laboratory results: None

Microscopic Description:

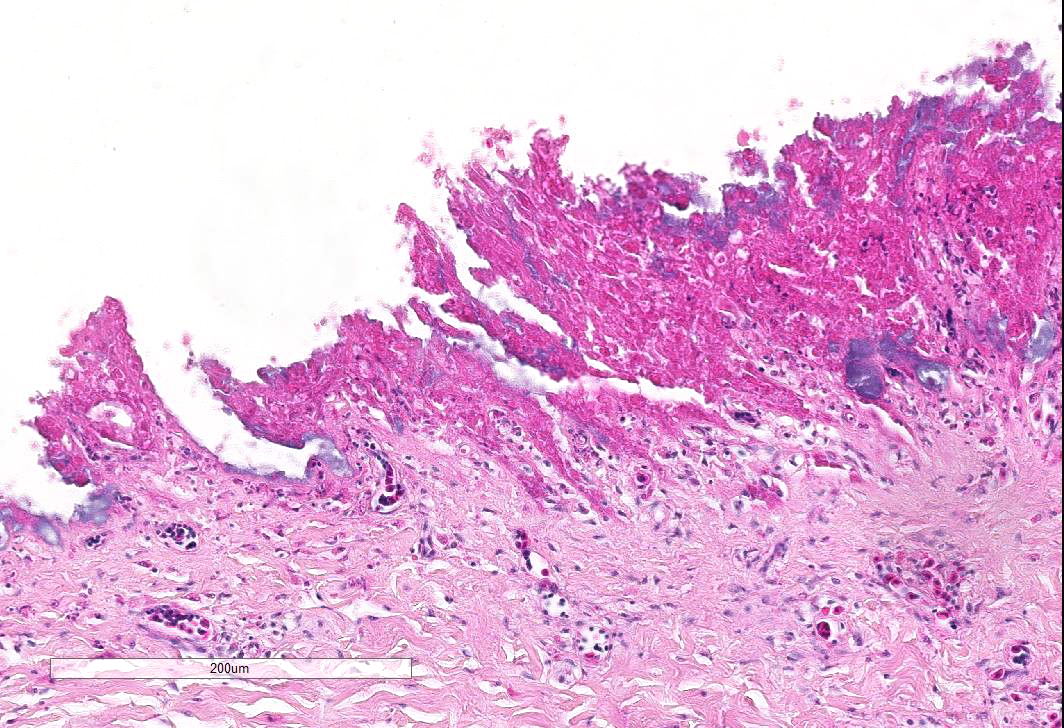

Esophagus: Up to 70% (variable among sections) of the mucosal lining and 100% of the esophageal glands are severely ulcerated and lost with accumulation of necrotic debris, fibrin and degenerated heterophils.

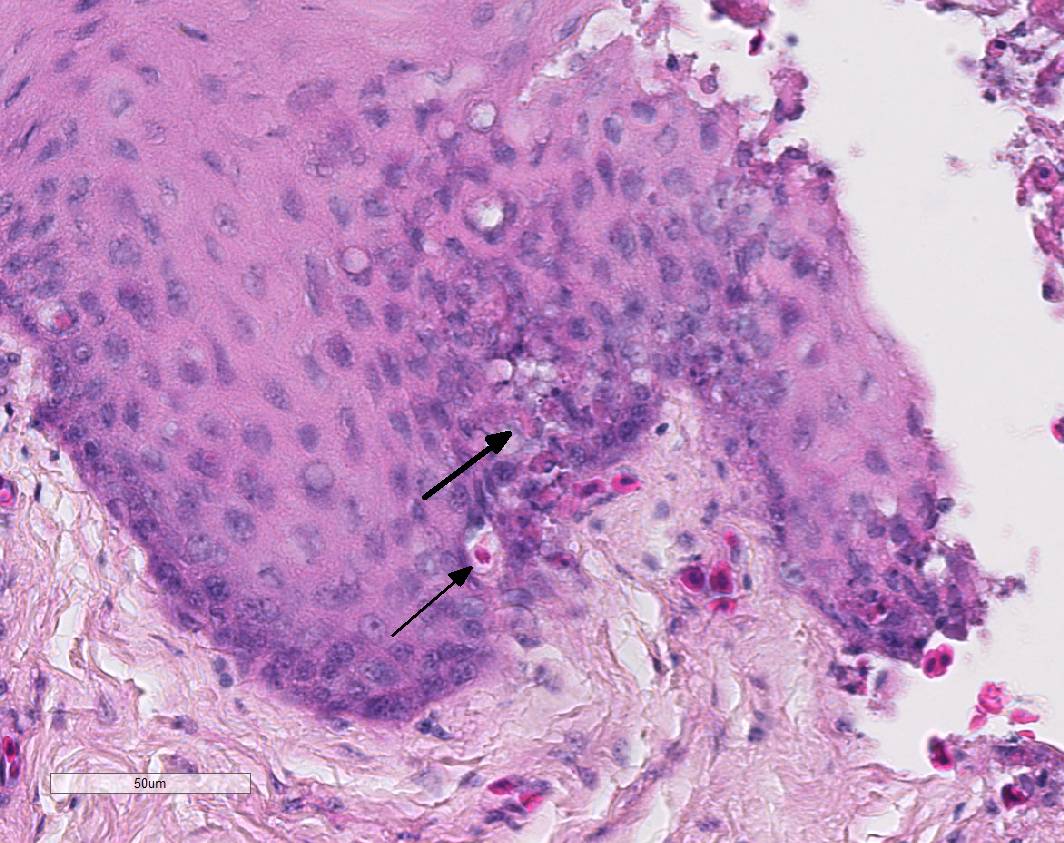

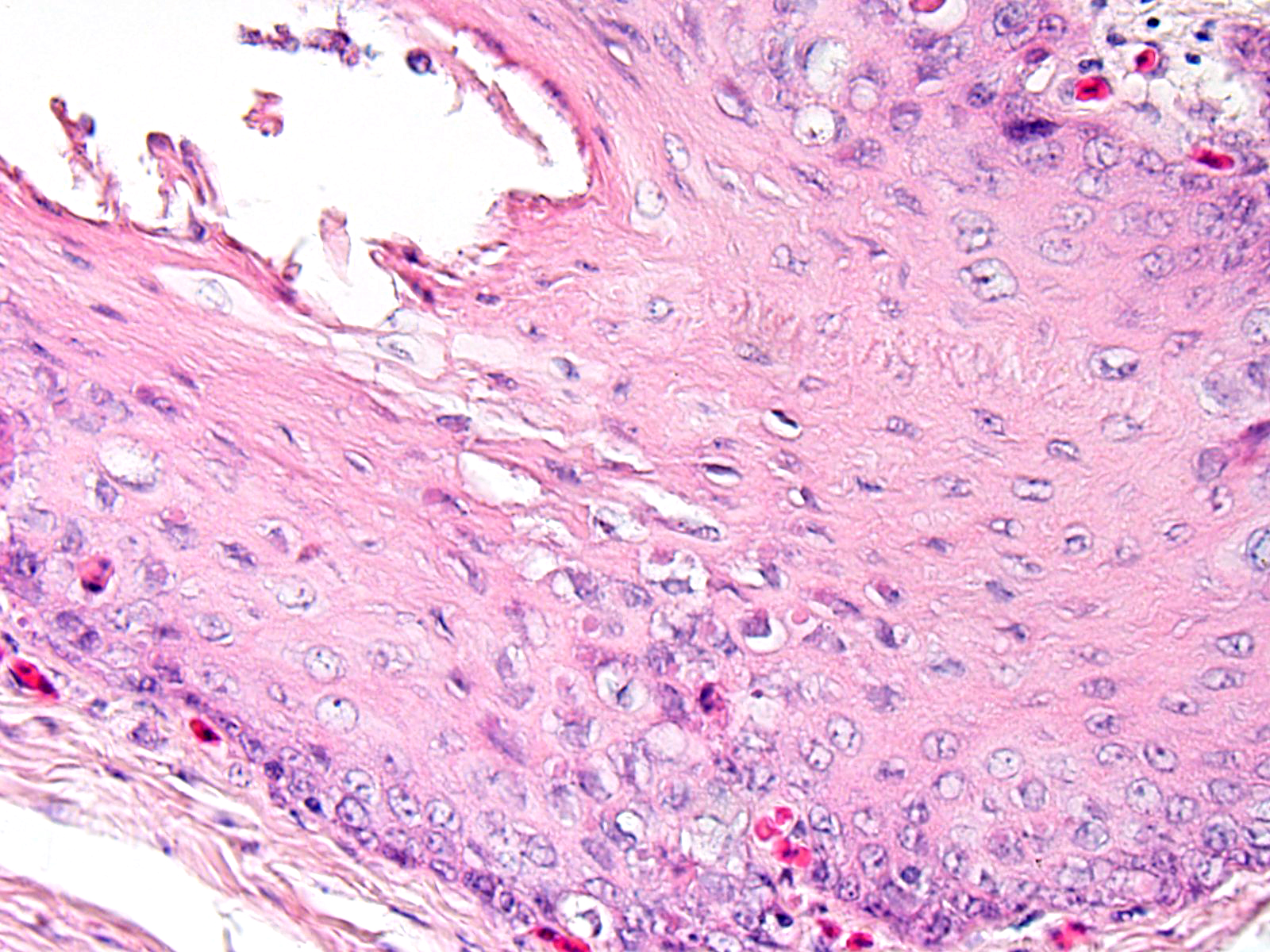

In the mucosal lining, epithelial cells are variably severely sloughed and admixed with many viable and degenerated heterophils, lesser numbers of foamy reactive macrophages and lesser numbers of small mature lymphocytes in association with aggregates of 1-2 μm basophilic coccoid bacteria. Variable percentages of residual epithelial cells have glassy homogeneous appearance with loss of cellular details and maintenance of nuclear outlines (coagulative necrosis). Occasionally, epithelial cells have 7-10 µm in diameter, irregularly round, brightly eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies that marginate the nuclear chromatin. Occasionally, intracytoplasmic inclusions are also present. Multifocally, cells of the basal layer have intracytoplasmic optically empty large vacuoles (hydropic degeneration).

Diffusely esophageal glands are ulcerated and filled by abundant pyknotic, karyolytic and karyorrhectic cellular debris (colliquative necrosis) and moderate amount of fine fibrillar material (fibrin) in association with a moderate number of foamy reactive macrophages and occasional karyolytic heterophils. In the submucosa, moderate edema, multifocal hemorrhage and mild, multifocal infiltration by a moderate numbers of heterophils and rare lymphocytes are visible. Blood vessels are diffusely and severely hyperemic.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Esophagus. Severe multifocal to locally extensive acute necrotizing and ulcerative esophagitis with epithelial intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies consistent with herpesvirus inclusions.

Name of the Disease: Duck plague or duck viral enteritis (DVE)

Etiology: Anatid herpesvirus-1 or DVE virus

Contributor’s Comment The presence of esophageal necrosis, intranuclear and intracytoplamic inclusion bodies, and the species affected were all information consistent with duck viral enteritis (anatid herpesvirus 1/AnHV-1).

Duck viral enteritis (DVE) is an acute, contagious and lethal disease that affects ducks, geese and swans.9 Currently, DVE is considered one of the most widespread and devastating diseases of waterfowl of the Anatidae family because of its ample distribution, wide host range, and relatively high morbidity and mortality.13 Adult ducks of Muscovy lineage (Cairina moschata domesticus) are the most susceptible DVE.2 In a recent report, the presence of DEV was found predominantly in wild ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) and mute swans (Cygnus olor), while the graylag geese (Anser anser), tundra bean geese (Anser fabalis), and grey herons (Ardea cinerea) were less affected.12 The virus may have crossed between different orders and families and adapted to new hosts, developing the characteristic form of the disease.8

Duck enteritis virus (DEV) is the causative agent of DVE and was alternatively known as anatid herpesvirus 1 (AnHV-1) and duck plague virus (DPV). Recent studies based on complete gene sequencing of Chinese virulent duck enteritis showed that the overall genome organization of DEV follows that of the alphaherpesviruses.13

DVE can be transmitted by direct contact between infected and susceptible birds or indirectly by contact with a contaminated environment.9 Morbidity rate may reach 67% in flocks and mortality rate may be up to 42.2% with a drop in egg production of 45% within 4 days of disease outbreak.11 Mortality usually occurs from 1-5 days after the onset of clinical signs and in chronic cases, death occurs in immunosuppressed birds. Birds recovering from disease may become carriers and may shed the virus in the feces or on the surface of eggs over a period of years.10

Clinical signs of DVE include cyanosis, lethargy, listlessness, head tilt, unwillingness to eat, photophobia, ataxia and paresis, nasal discharge, ruffled feathers, bloody diarrhea and death within 2-3 hours of onset of clinical signs.2,5,11 Sudden death has been reported in several outbreaks.8,11

Gross findings include petechial hemorrhages of serosal linings, lungs, heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, pancreas, ovarian follicles, and often small and large intestinal serosa. Hemorrhagic enteritis with intraluminal bloody contents admixed with mucus, necrotizing, ulcerative and diphtheritic inflammation of the oropharynx, proximal trachea, esophagus, small intestine and cloaca accompanied by severe hepatic degeneration and multifocal necrotizing hepatitis have also been identified in several ducks.2,8,11

Histological findings are characterized by necrosis in the digestive tract, reproductive and upper respiratory tract, liver, and spleen. Hemorrhages in digestive tract, spleen, and liver and heterophils and macrophages infiltrating the lesions are visible.2

Esophageal lesions are characterized by swollen epithelial cells with a pale, dispersed, or vacuolated cytoplasm, individual epithelial cell necrosis or occasional larger foci of extensive epithelial necrosis and erosion and numerous large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusion bodies.1,2 Other common findings include lymphoid depletion and necrosis in the bursa of Fabricius and vascular damage in all affected organs.14 Some authors describe the presence of two types of intranuclear inclusion bodies (IIBs) associated with herpesvirus infection: (a) small acidophilic IIBs surrounded by a clear halo and (b) slightly basophilic IIBs occupying the entire nucleus.8

Herpesvirus inclusion bodies are classically distinguished into two subtypes: Cowdry A inclusions are small, round eosinophilic and separated from the nuclear membrane by a halo. Cowdry B inclusions are large, glassy, eosinophilic, and centrally located, marginating nuclear material to the rim of the nucleus.6

Ultrastructurally, intranuclear non-enveloped viral particles measure about 110 nm in diameter with hexagonal shaped and variable electron-density in the cores. These are randomly distributed in the nucleus or aligned close to the nuclear envelope. The intracytoplasmic viral particles are arranged in clusters or as solitary enveloped virions measuring 200 to 250 nm in diameter.8

The definitive diagnosis of DVE is made by electron microscopy, direct immunofluorescence, PCR and immunohistochemistry.2,8,13,14

The main differential diagnoses for DVE (Anatid herpesvirus-1) include viruses responsible for both intracytoplasmic and intranuclear viral inclusions, such as cytomegaloviruses (subfamily Betaherpesvirinae), gallid herpesvirus-2 (Marek’s Disease virus) and paramyxoviruses.1,3,7

Contributing Institution:

DIMEVET-Anatomical Pathology Section

Via Celoria 10

20133 Milano

ITALY

JPC Diagnosis: Esophagus: Esophagitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with mucosal epithelium intranuclear inclusions.

JPC Comment: The contributor has done an excellent job in describing this viral disease particular to waterfowl. Duck viral enteritis, first reported in the Netherlands in 1927, was originally identified as a duck-adapted strain of avian influenza until 1942, when it was identified as a distinct viral disease of ducks following fruitless transmission attempts to galliform birds, mice, guinea pigs, rabbits rats and mice.3

The virus has caused outbreaks in the US and Europe, most often in proximity to large bodies of water where wild waterfowl may mix with domestic or farmed animals. Horizontal water-borne transmission of the virus is considered to play a primary role, with vertical transmission being of questionable importance.3

Age is a particular factor, with adult breeders showing the highest mortality and birds less than 7 days resistant to infection. Being a member of the Alphaherpesvirinae, latent infections may be seen in birds, with latent infections being maintained up to 4 years in the trigeminal ganglion, lymphoid tissues, and peripheral blood lymphocytes. Convalescent birds are immune to reinfection; however, they may maintain a latent infection and migratory birds may shed the virus, initiating new outbreaks in remote areas.3

In older birds, the characteristic lesions are those of hemorrhage due to necrosis of small capillaries and venules. In younger birds, lymphoid lesions are more prevalent. The virus induces both apoptosis and necrosis of lymphocytes in lymphoid tissues throughout the body, to include the bursa, spleen, and thymus initiating at first hemorrhagic lesions and then in convalescent birds, thymic atrophy (a sign often used in condemning carcasses following outbreaks). Necrosis and hemorrhage of GI lymphoid tissue often results in annular bands of hemorrhage in the duodenum and ceca. The immunsuppressive effects of low-virulence duck enteritis virus (DEV) may result in an increase in secondary bacterial infections including Riemerella anatipestifer, Pasteurella multocida, and E. coli in younger birds. Another characteristic gross finding in outbreaks in penile phimosis. 3

The presence of intranuclear and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions is an oddity in viral histopathology. As a DNA virus, viral replication occurs within the nucleus. The cytoplasmic inclusions are membrane-bound vacuoles containing enveloped virus and nuclei containing viral nucleocapsids.3

References:

- Barr BC, Jessup DA, Docherty DE, Lowenstine LJ. Epithelial intracytoplasmic Herpes viral inclusions associated with an outbreak of duck virus enteritis. Avian Dis. 1992;36:164-168.

- Campagnolo ER, Banerjee M, Panigrahy B, Jones RL. An outbreak of duck viral enteritis (duck plague) in domestic Muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata domesticus) in Illinois. Avian Dis. 2001;45:522-528.

- Shama K, Kumar N, Saminathan M, Tiwari R, Karthik K, Kumar MA, Palanivelu M, Shabbir MZ, Malik YS, Singh RK. Duck virus enteritis (duck plague) – a comprehensive update. Vet Q 2017 37(1):57-80.

- Fauquet C, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. Virus taxonomy: eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005.

- Hanson JA, Willis NG. An outbreak of duck virus enteritis (duck plague) in Alberta. J Wildl Dis. 1976;12:258-262.

- Kelly NP, Raible MD, Husain AN. Pathologic Quiz Case: An 11-day-old boy with lethargy, jaundice, fever, and melena. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:469-470.

- Knowles DP. Herpesvirales. In: MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. Fenner’s Veterinary Virology. 4th ed. London, UK: Academic Press; 2011:197–198.

- Salguero FJ, Sanchez-Cordon PJ, Nunez A, Gomez-Villamandos JC. Histopathological and ultrastructural changes associated with herpesvirus infection in waterfowl. Avian Pathol. 2002;31:133-140.

- Sandhu TS, Metwally SA. Duck Virus Enteritis (Duck Plague). In: Saif YM, Fadly AM, Glisson JR, McDougald LR, Nolan LK, Swayne DE, eds. Diseases of Poultry. 12th ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 2008: 384-393.

- Shawky S, Schat KA. Latency sites and reactivation of duck enteritis virus. Avian Dis. 2002;46:308-313.

- Uma Rani R, Muruganandan B. Outbreak of Duck Viral Enteritis in a Vaccinated Duck Flock. Sch J Agric Vet Sci. 2015;2:253-255.

- Wo?niakowski G, Samorek-Salamonowicz E. First survey of the occurrence of duck enteritis virus (DEV) in free-ranging Polish water birds. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1439-1444.

- Wu Y, Cheng A, Wang M, et al. Complete genomic sequence of Chinese virulent duck enteritis virus. J Virol. 2012;86:5965.

- Xuefeng Q, Xiaoyan Y, Anchun C, Mingshu W, Dekang Z, Renyong J. The pathogenesis of duck virus enteritis in experimentally infected ducks: a quantitative time-course study using TaqMan polymerase chain reaction. Avian Pathol. 2008;37:307-310.

References:

- Adair BM, Fitzgerald SD. Group I Adenovirus infections. In: Diseases of Poultry. 12th Iowa State Press; 2008:252-266.

- Garmyn A, Bosseler L, Braeckmans D, Van Erum J, Verlinden M. Adenoviral gizzard erosions in two Belgian broiler farms. Avian Dis 2018; 62(3):322-325.

- Hollell JD, McDonald W, Christian RG. Inclusion body hepatitis in chickens. Can Vet J 1970; 11:99-101.

- Ramis A, Marlasca MJ, Majo N, Ferrer L. Inclusion body hepatitis (IBH) in a group of eclectus parrots (Eclectus roratus). Avian Pathol 1992; 21(1):165-9.

- Randall CR and Reece RL. Color Atlas of Avian Histopathology. Mosby-Wolfe, Times Mirror International Publishers Limited; 1996: 95-96.

- Yugo DM, Hauck R, Shivaprasad HL, Meng XJ. Hepatitis virus infectious in poultry. Avian Dis 2016; 60:576-588.

- Zhao J, Zhong Q, Zhao Y, Hu Y, Zhang GZ. Pathogenicity and complete genme characterization of fowl adenoviruses isolated from chickens associated with inclusion body hepatitis and hydropericardium syndrome in China. Plos One 2015 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0133073