Signalment:

Six-year-old, castrated male, boxer, (

Canis familiaris).The

dog presented with a 20-day history of seizure-like activity (lateral

recumbency, drooling, and paddling) with increasing frequency. Phenobarbital

administration controlled the symptoms for several weeks, but the dog gradually

became lethargic and inappetant with head twitching behavior. The owners

elected euthanasia due to concern about the dogs quality of life.

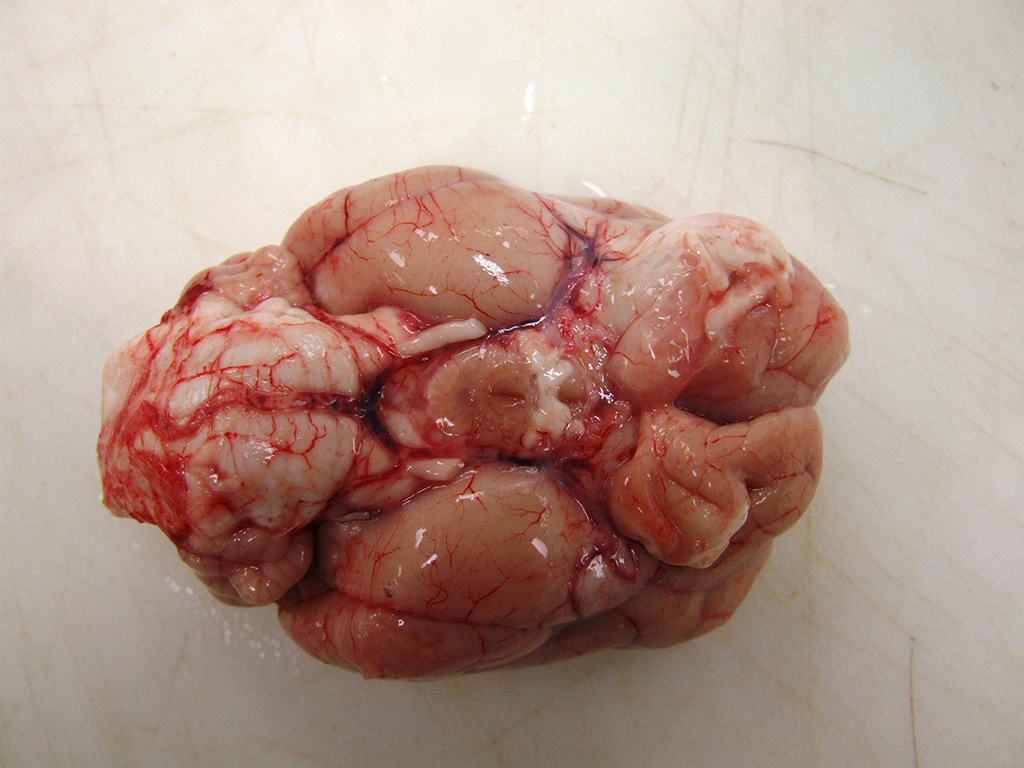

Gross Description:

The

rostral aspect of the right frontal lobe of the brain was enlarged, with

shallow sulci and flattened gyri, and was deviated left of the midline. The

brain was fixed in formalin and sectioned for examination. The cranioventral

portion of the right cerebral hemisphere contained a gray, translucent,

gelatinous, 2cm x 2cm x 4cm mass, extending from the frontal lobe of the

cerebrum into the mesencephalon.

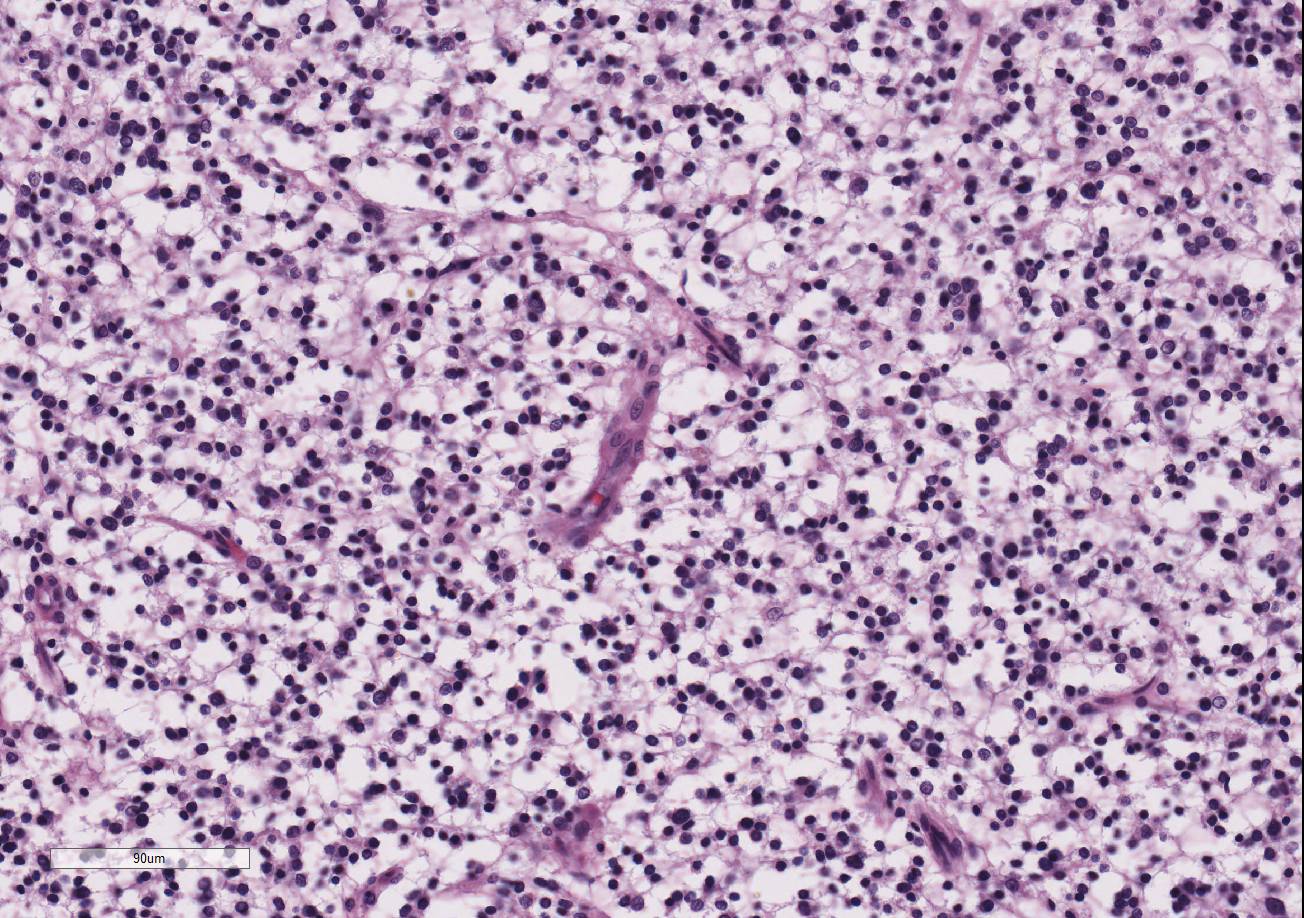

Histopathologic Description:

Within the white matter of the

cerebral cortex, there is a poorly demarcated, unencapsulated, in-filtrative

neoplastic mass. The neoplasm is composed of round to polygonal cells arranged

as a loose meshwork or occasionally as closely packed sheets with a honeycomb

appearance and scant fibro-vascular stroma. Neoplastic cells are 10-14 microns

in diameter and have distinct cell borders; scant to moderate amounts of

eosinophilic, fibrillar cytoplasm; a prominent perinuclear clear zone (peri-nuclear

halo); and small, irregularly round, hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct

nucleoli. The mitotic rate is less than one per ten 400x high power fields.

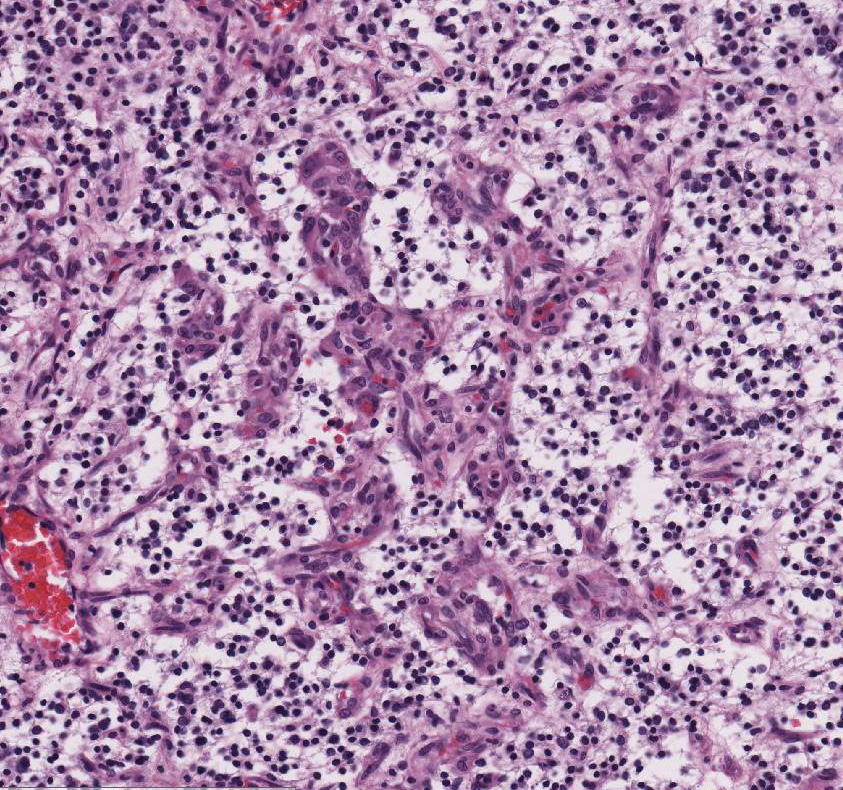

Capillary blood vessels within the mass are prominent with marked endothelial

hypertrophy. Other variable features that are present in some slides: scattered

foci of hemorrhage, glomeruloid microvascular proliferation, and pseudocystic

cavities containing homo-geneous, lightly basophilic (mucinous) material. Neoplastic cells were negative for GFAP on immunohistochemical staining.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Brain (cerebrum): Oligodendroglioma.

Lab Results:

Bloodwork was unremarkable.

Condition:

Oligodendroglioma

Contributor Comment:

This

case had a classic signalment and presentation for canine oligodendrogliomas.

Oligo-dendrogliomas occur most commonly in dogs, particularly in older animals

and brachycephalic breeds (boxers, Boston terriers, and bulldogs), and rarely

in other species including humans, cats, cattle, and horses.

1,2,9 In

a study involving 173 dogs, it was found that dogs with oligo-dendrogliomas are

3.6 times more likely to have seizures compared with dogs with other types of

primary brain tumors.

9 Other common presenting clinical complaints

include mentation change, vision loss, neck pain, and vestibular syndrome.

9

Bloodwork is usually unremarkable, as it was in this case. The most

frequent location for oligo-dendrogliomas is the white or gray matter of the

cerebral hemispheres, particularly the olfactory area and rostral lobes, but

can occur

caudally or in the spinal cord.

5,9 Grossly, they appear as large,

soft, gelatinous or mucoid, well-demarcated masses with grayish-blue matrix and

gray to pink stroma on cut section.

1,2,5 Histologically,

oligodendrogliomas are moderately to highly cellular, and characterized by

dense sheets of uniform cells.

1,5 Delayed fixation causes an arti-factual

"honeycomb" cell pattern with a perinuclear halo effect.

1,2,5

Prominent microvascular proliferation is common, often with formation of a

delicate "chicken-wire" pattern or vascular loops with

glomerular-like tufts, as seen in this case.

1,2,5 Foci of

hemorrhage, mineralization, or microcystic areas containing blue-staining

mucinous material may also be present.

1,2,5 Tumors can extend along

or through the leptomeninges or ependymal surfaces; intraventricular growth may

be associated with widespread intraventricular metastases.

5 Anaplastic

oligodendrogliomas are characterized by focal or diffuse anaplasia with

prominent proliferation of glomeruloid vessels at the tumor margins, nuclear

polymorphism, and increased mitotic index (1-2 per HPF), necrosis, and/or

meningeal infiltration.

1 Intermingled astrocytes are common, and in

some tumors polymorphic multinucleated giant cells may be numerous.

1

Often, areas of necrosis with peripheral glial cell palisading can be found.

5

Due to the lack of malignant features, in this case, the tumor was diagnosed as

a benign oligodendroglioma.

Oligoastrocytomas

are rare mixed glial tumors composed of neoplastic astrocytes and

oligodendroglia, in which the two cell populations may be diffusely

intermingled or in geographically distinct clusters.

1,2,5 Canine

oligoastrocytomas are predominantly composed of oligodendroglial cells with at

least 25-30% neoplastic astrocytes; lower percentages of astrocytic elements

are interpreted as reactive proliferating cells within oligodendrogliomas.

1,5

Anaplastic (malignant) oligoastrocytomas are characterized by increased

cellularity, nuclear atypia, high mitotic activity, vascular proliferation, and

necrosis, and may be difficult to differentiate from high-grade astrocytomas.

1

Ultrastructurally,

oligodendrogliomas have no obvious distinguishing features, appearing as cells

with sparse microtubules and few organelles in the cytoplasm and frequent

desmosomal junctions between cells.

5

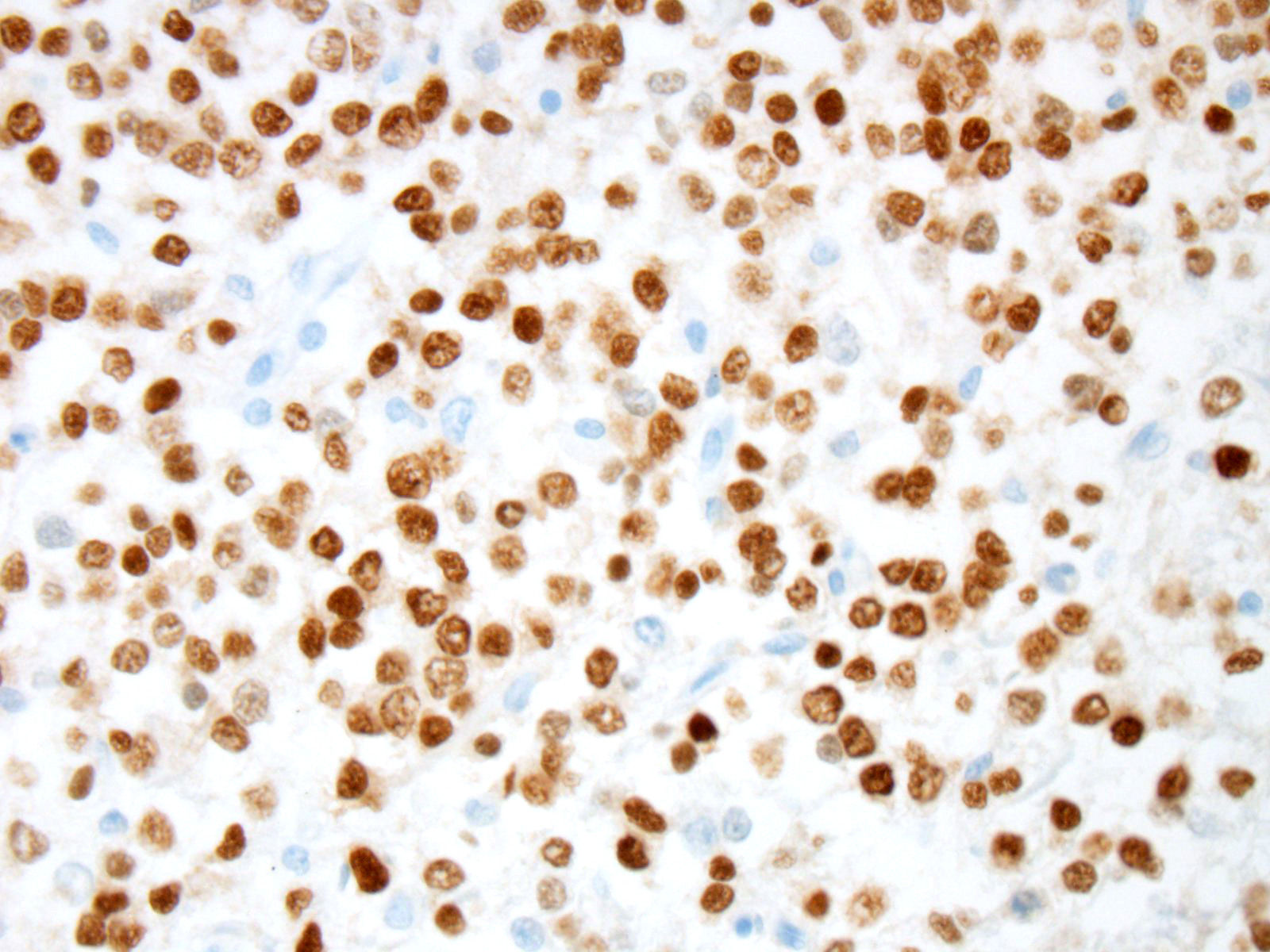

Historically,

diagnosis of oligo-dendrogliomas has relied on gross and microscopic tumor

morphology and negative GFAP staining of cells, due to lack of specific

markers.

2,4,5 In recent years, several markers have been

investigated, including doublecortin, olig2, and CNPase.

3,4

Doublecortin is a cytoplasmic neuronal precursor marker which is frequently

expressed in oligodendrogliomas and embryonal neoplasms such as neuro-blastomas

and PNETs, but infrequently expressed in astrocytomas.

3 Olig2 is a

nuclear transcription factor that is required for oligodendrocyte

differentiation but not astrocyte development, and has been shown to stain all

oligodendrogliomas in one study.

4 Non-neoplastic astrocytes do not

stain with Olig2; however, astrocytomas can have positive nuclear staining.

4

CNPase is a cytoplasmic phosphodiesterase that is expressed early in

myelination.

4 It stains normal and neoplastic oligodendrocytes, but

weak cytoplasmic staining of canine astro-cytomas can also occur.

4 A

combination of negative GFAP staining and positive Olig2 staining may be most

helpful in identification of oligodendrogliomas. Positive staining for factor

VIII-like antigen and smooth muscle actin highlights the neoplasm's

characteristic microvascular pro-liferations.

5 In our case, the

neoplasm stained negatively for GFAP. No staining for the other potential

oligodendroglioma markers was attempted.

JPC Diagnosis:

Brain, cerebrum: Oligo-dendroglioma, boxer,

Canis familiaris.

Conference Comment:

Despite

some moderate slide variability, the contributor provides a great example and

com-prehensive review of oligodendrogliomas in the canine central nervous

system (CNS). Oligo-dendrogliomas are the third most common primary neoplasm in

the dog brain, after meningiomas and astrocytomas.

6 These soft

gelatinous neoplasms typically arise in the telencephalic or diencephalic

cerebral white matter, but can uncommonly occur in the brainstem, spinal cord,

or within the ventricular system as a single tumor or as multiple concurrent

oligodendrogliomas as a result of metastasis through the cerebro-spinal fluid.

2,6,8

Oligodendrogliomas

originate from oligo-dendrocytes, which normally function

to provide support and myelination to axons within the white

matter tracts of the CNS.

7 Each oligodendrocyte can envelop up to 50

axons based on the thickness of the myelin sheath needed. Oligodendrocytes also

serve a role in the production of neurotropic factors important for

the remyelination of demyelinated axons in the CNS.

7 Schwann cells

provide an equivalent function in the peripheral nervous system (PNS); however,

unlike oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells can only envelope one part of a single

axon. Schwann cells are also extremely important in axonal regeneration in the

PNS.

10

As mentioned by the

contributor, positive immunohistochemical staining for oligo-dendrocyte

transcription factor-2 (Olig2) in combination with negative glial fibrillary

acidic protein (GFAP) has been shown to be an extremely useful tool in the

diagnosis of oligodendrogliomas. The proportion of Olig2-positive cells has

been shown to be significantly higher in oligodendrogliomas when compared with

other glial tumors such as astrocytoma and oligoastrocytoma, mentioned above.

4,6

Prior to the conference, an Olig2 and GFAP stains were performed by the Joint

Pathology center. In this case, neoplastic cells showed strong and diffuse

intranuclear immunoreactivity to Olig2. Expression of intranuclear Olig2 immuno-reactivity

is restricted to the neoplasm and resident oligodendrocytes within the

unaffected section of cerebrum. Additionally, neoplastic cells are diffusely

immunonegative for GFAP. The GFAP-positive cells noted by conference

participants at the periphery and within the neoplasm are interpreted as

reactive astrocytes, which can occur due to tumor-induced activation of the residential astroglial network.

This staining pattern is consistent with the contributors diagnosis of an

oligodendroglioma, in this case.

2,4,6,8

References:

1. Burger

PC, Scheithauer BW: Tumors of neuroglia and choroid plexus. In:

AFIP Atlas

of Tumor Pathology, Series 4, Tumors of the Central Nervous System. ed.

Silverberg SG. Washington DC: ARP Press; 2007:225-233.

2. Cantile

C, Youssef S. Nervous system. Maxie MG ed. In:

Jubb Kennedy and Palmer's

Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA:

Elsevier Saunders; 2016:400.

3. Ide,

Uchida K, Kikuta F, Suzuki K, Nakayama H. Immunohistochemical characterization

of canine neuro-epithelial tumors.

Vet Pathol. 2010; 47(4)741-750.

4. Johnson

GC, Coates JR, Wininger F. Diagnostic immunohistochemistry of canine and feline

intracalvarial tumors in the age of brain biopsies.

Vet Pathol. 2014;

51(1)146-160.

5. Koestner

A, Higgins RJ. Tumors of the nervous system. In:

Tumors in Domestic Animals.

ed. Meuten DJ. 4th ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press; 2002:703-706.

6. Kovi

RC, Wünschmann A, Armién AG, Hall K, Carlson T, Shivers J, Oglesbee MJ. Spinal meningeal

oligo-dendrogliomatosis in two boxer dogs.

Vet Pathol. 2013;

50(5):761-764.

7. Kremer

D, Gottle P. et al. Pushing forward: Remylination as the new frontier in CNS

disease.

Trends Neurosci. 2016; 39(4):246-263.

8. Rissi

DR, Levine JM, et al. Cerebral oligodendroglioma mimicking intra-ventricular

neoplasia in three dogs.

J Vet Diagn Invest. 2015; 27(3):396-400.

9. Snyder JM,

Shofer FS, Van Winkle TJ, Massicotte C: Canine intracranial primary neoplasia:

173 cases (1986-2003).

J Vet Intern Med. 2006; 20:669-675.

10. Toy

D, Namgung U. Role of glial cells in axonal regeneration.

Exp neurobiol.

2013; 22:68-76.