Signalment:

Gross Description:

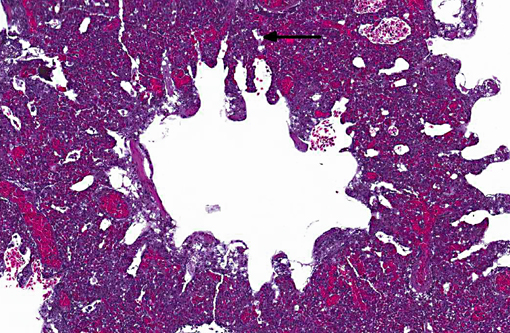

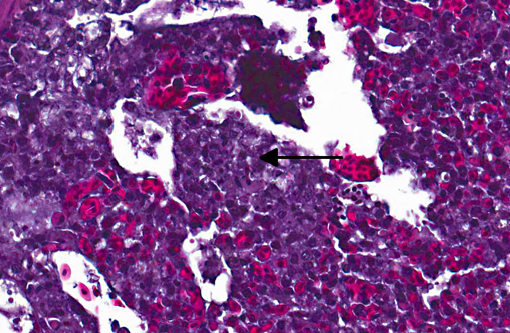

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

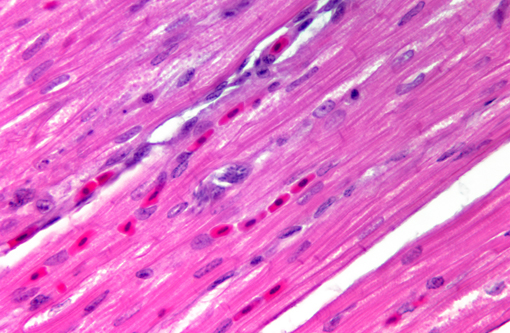

Sarcocystis falcatula (and S. falcatula-like organisms) is typical of the genus in that it utilizes a two-host life cycle. The only known definitive host in North America is the opossum (Didelphis virginiana) but unlike most Sarcocystis species it can utilize a number of avian species as intermediate hosts.(3,5,6,7,8) Susceptible birds ingest sporocysts shed in the feces of opossum, which release sporozoites once in the intestinal tract. Tissue invasion and local asexual reproduction ensues, followed by additional cycles of merogony in capillaries and venules throughout the body.(6) In the lungs, where merogony is often most pronounced, endothelial cells become swollen with cytoplasmic meronts. The presence of protozoa can lead to vascular obstruction, perivasculitis and vasculitis, and significant interstitial and airway edema.(2,3,6) Pulmonary lesions can be fatal in birds with heavy protozoal burdens, such as the quail in this case. In addition to the lungs, merogony has been noted to occur in the liver, spleen, pancreas, adrenal glands and heart.(6) Other than the liver, the protozoal presence is typically insignificant with mild or no inflammation.(6) In these quail, endothelial cells of the heart were the only extrapulmonary site of merogony and low numbers of organisms were occasionally associated with mild lymphohistiocytic myocarditis. In birds that survive the initial reproductive cycles, sarcocysts typically develop in skeletal and cardiac muscle, where they remain until ingestion by the definitive host.(2,3,6,7) Sarcocysts were not identified in the case presented here, presumably an effect of how quickly the quail succumbed to pulmonary disease.Â

Multiple opossum were trapped on zoo grounds following initial diagnosis of this disease. In addition to direct infection via opossum feces, paratenic hosts or mechanical vectors, such as cockroaches and other insects, can cause infection indirectly.(2)

Confirmation of S. falcatula-like organisms in avian patients requires diagnostic evaluation beyond light microscopy. Individual merozoites can be mistaken for Toxoplasma or Neospora tachyzoites, and light microscopic morphology alone (of any stage) is not sufficient to differentiate individual Sarcocystis species.(3) Immunohistochemistry is available for S. falcatula, and organisms in previous thick-billed parrot sarcocystosis cases at our institution reacted positively to S. falcatula antisera. As S. neurona can also reactive positively to this antisera, S. neurona-specific immunohistochemistry was also performed and was negative. (3) Ultrastructural evaluation of Sarcocystis spp. reveals typical apicomplexan features, such as a conoid and micronemes; unlike Toxoplasma, however, Sarcocystis spp. are intracytoplasmic rather than within a parasitophorous vacuole. Rhoptries are likely absent in S. falcatula-like organisms, but this observation differs between authors.(2,5,8)

Recent molecular investigations into the genus have revealed differences between organisms previously grouped together as S. falcatula.(3) Such research suggests the presence of multiple species, thus prompting the use of S. falcatula-like rather than definitive identification.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

| Sarcocystis sp. | Intermediate host | Definitive host | Comments |

| S. cruzi | Cattle | Domestic and wild canids | Eosinophilic myositis; Hemolysis, abortion, lymphadenitis, tail tip sloughing, death |

| S. gigantic | Sheep | Cat | Only species of domestic animals visible to naked eye |

| S. tenella (S. ovicanis) | Sheep | Dog | Encephalomyelitis; severe disease in lambs |

| S. miescheriana | Swine | Domesitc and wild canids | Diarrhea, myositis, lameness |

| S. neurona | Birds/horses* | Opossum | Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis |

References:

2. Clubb SL, Frenkel JK. Sarcocystis falcatula of opossums: transmission by cockroaches with fatal pulmonary disease in psittacine birds. J. Parasitol. 1992;78(1):116-124.

3. Dubey JP, Garner MM, Stetter MD, Marsh AE, Barr BC. Acute Sarcocystis falcatula-like infection in a carmine bee-eater (Merops nubicus) and immunohistochemical cross reactivity between Sarcocystis falcatula and Sarcocystis neurona. J. Parasitol. 2001;87(4):824-832.

4. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 1. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:435.

5. Smith JH, Meier JL, Neill JG, Bos ED. Pathogenesis of Sarcocystis falcatula in the budgerigar. I. Early pulmonary schizogony. Lab Invest. 1987;56(1):60-71.

6. Smith JH, Neill PJG, Box ED. Pathogenesis of Sarcocystis falcatula in the budgerigar. III. Pathologic and quantitative parasitologic analysis of extrapulmonary disease. J. Parasitol. 1989;75(2):270-287.

7. Smith JH, Neill PJG, Dillard EA III, Box ED. Pathology of experimental Sarcocystis falcatula infections of canaries (Serinus canarius) and pigeons (Columba livia). J. Parasitol. 1990;76(1):59-68.

8. Speer CA, Dubey JP. Ultrastructure of schizonts and merozoites of Sarcocystis falcatula in the lungs of budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). J. Parasitol. 1999;85(4):630-637.

9. Van Vleet JF, Valentine BA. Muscle and tendon. Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 1. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:266-268.Â