CASE I: 1326 (JPC 4118329)

Signalment:

Adult, female, cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis)

History:

This macaque was part of the primate colony at USAMRIID and was awaiting assignment to a research study. Although it was at USAMRIID for several months and had no history of clinical disease during this time, it was suddenly noticed to have weakness of the left arm and left leg. Further physical examination revealed an approximately 3 cm X 2.5 cm open wound on the back of its neck with a purulent discharge. Routine aerobic bacterial cultures of the wound yielded Staphylococcus aureus and other unremarkable species of bacteria. There appeared to be a fistulous tract on the neck that extended into the cervical spine and radiographs of this area revealed that several cervical vertebrae had "mottled" areas of decreased bone density. Because of the overall poor prognosis for this animal and its unsuitability for use in a research protocol, euthanasia was performed.

This monkey was being kept in a primate research colony that is under the purview of an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and this research colony is maintained in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facility where this primate colony is kept is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and adheres to principles stated in the 8th edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

Gross Pathology:

At necropsy, there was a tan purulent exudate that emanated from the wound on the right dorsal area of the neck. A fistulous tract extended from the open skin wound into the

underlying muscles and cervical vertebrae and appeared to also involve the cervical spinal cord.

An approximately 1 cm diameter white nodule was present in the left superior lung lobe and multiple pinpoint white foci were noted throughout the spleen and liver.

Laboratory Results:

None submitted.

Microscopic Description:

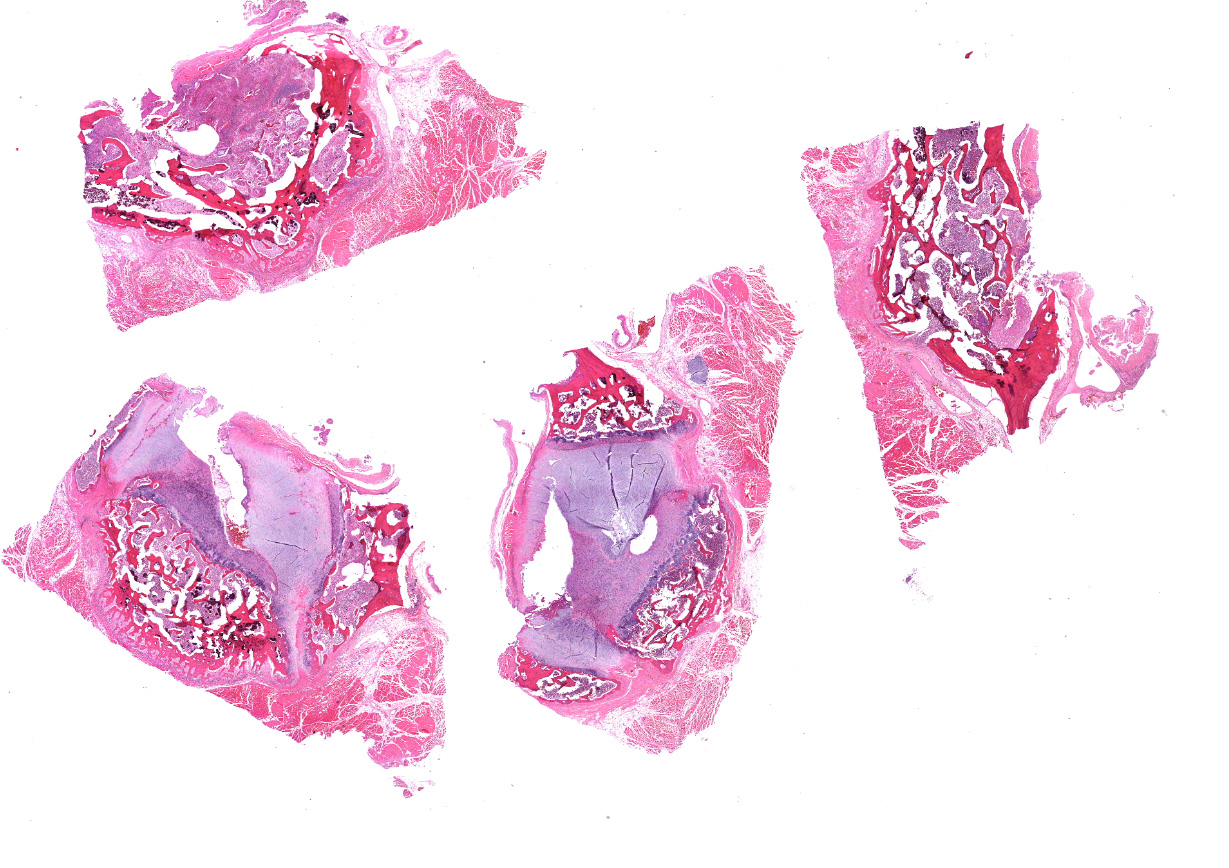

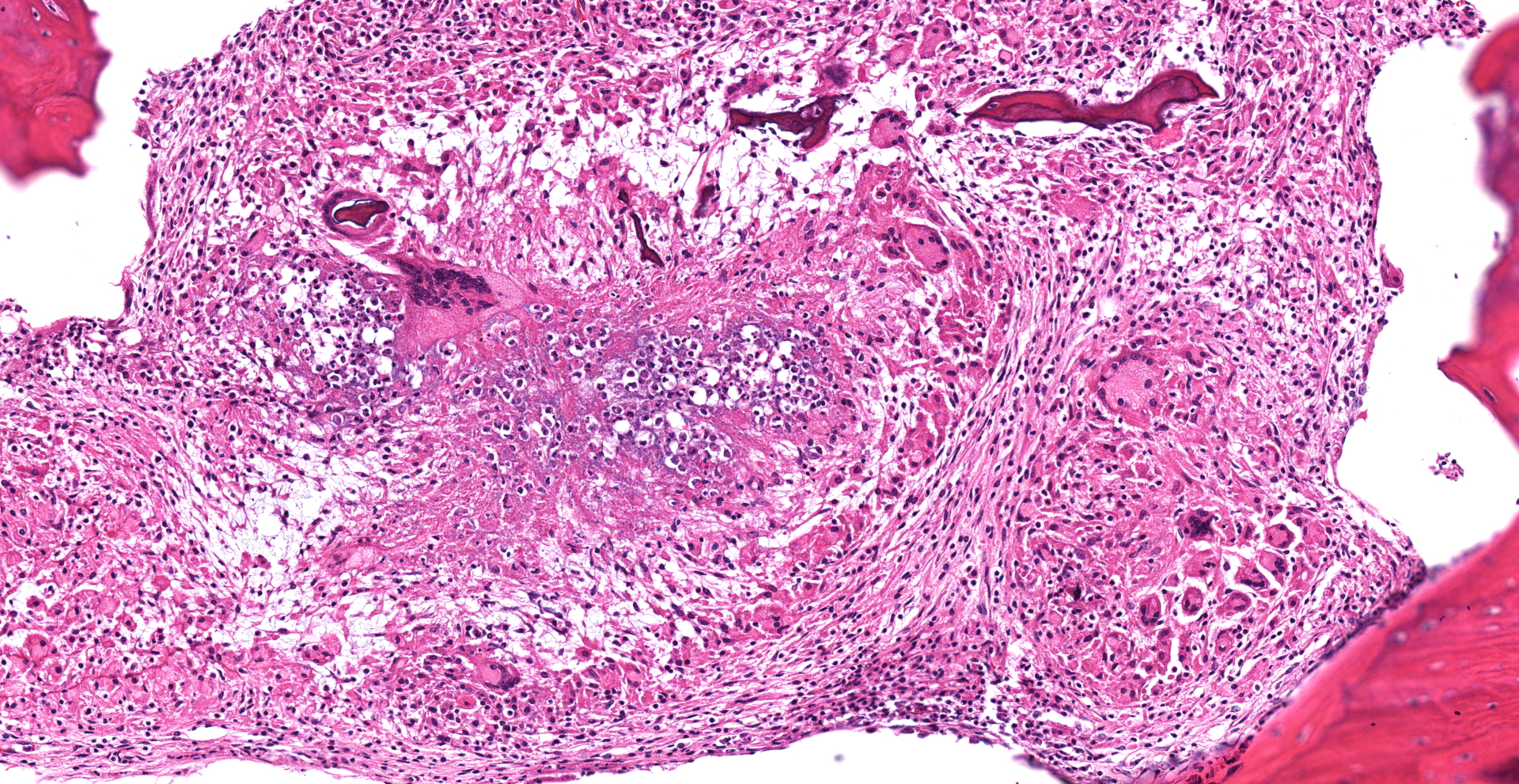

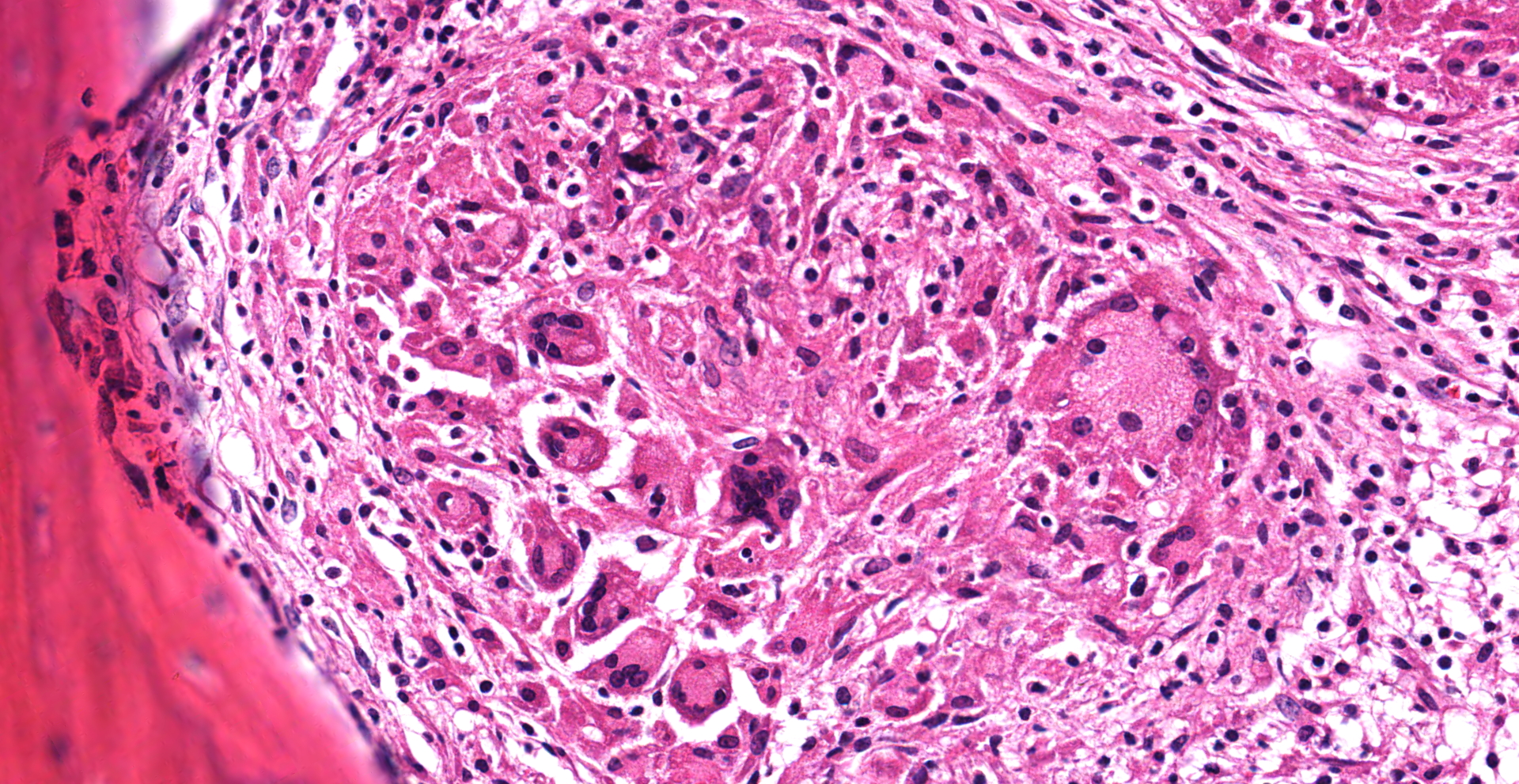

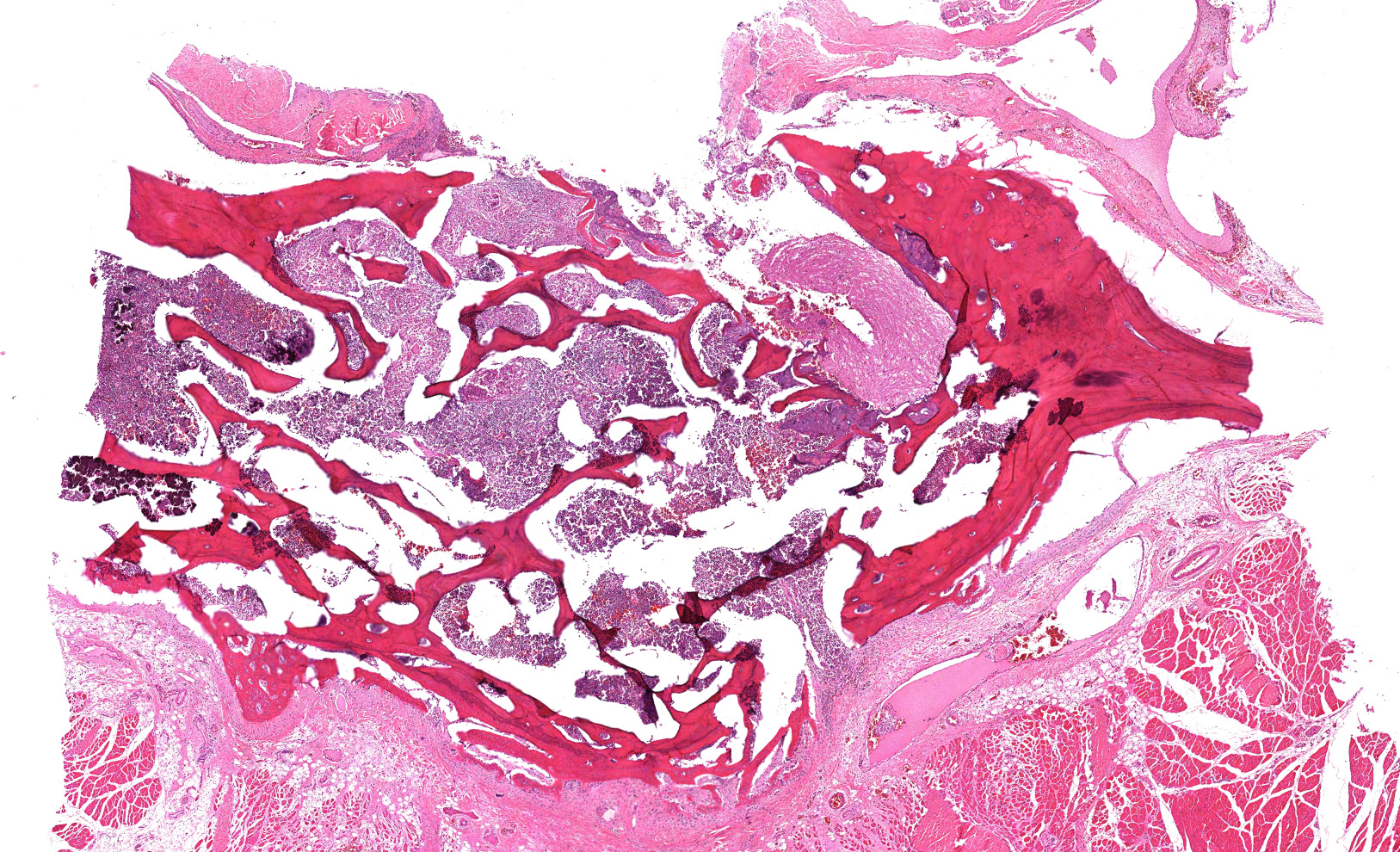

Cervical vertebrae (4 sections): Within the bone marrow, there are multifocal and coalescing cellular infiltrates composed of neutrophils, macrophages (primarily epithelioid), and multinucleated giant cells. There is often caseous necrosis in the centers of these infiltrates and fibroplasia is present multifocally around the periphery of the infiltrates. There is multifocal necrosis and/or resorption of bone spicules within the marrow cavities, as well as multifocal periosteal new bone formation and fibrosis along the outer margins of the vertebral cortices.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Cervical vertebrae; multifocal and coalescing chronic pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis, moderate to marked, with bone resorption, bone remodeling, and periosteal new bone formation.

Contributor's Comment:

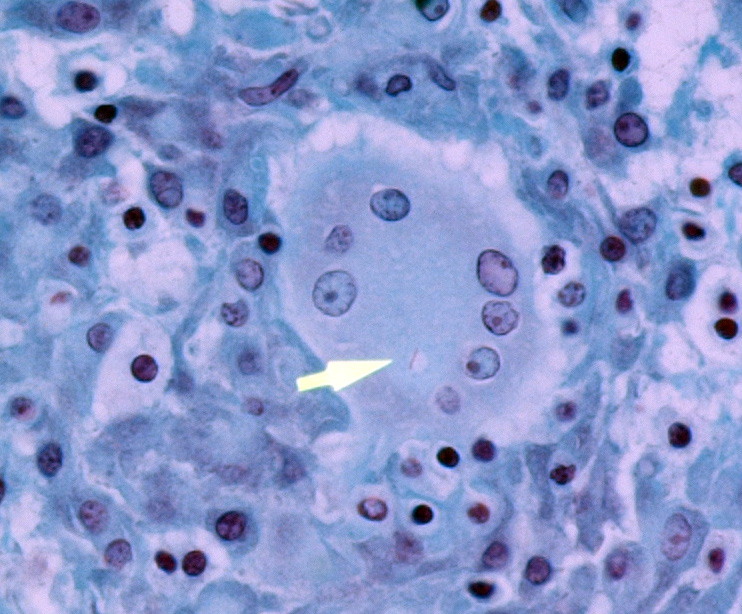

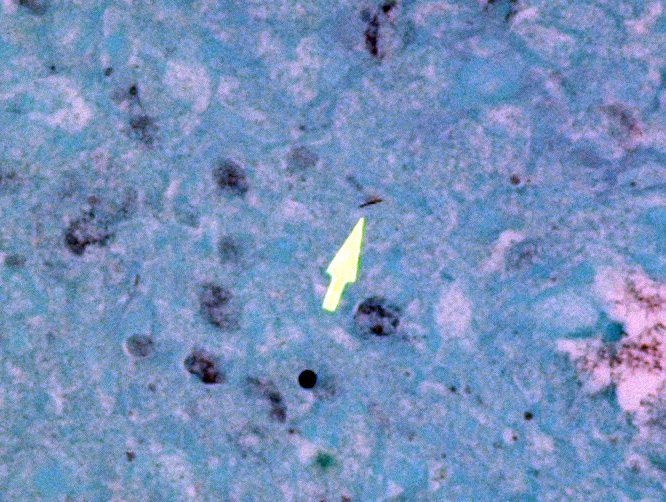

In addition to the lesions present in the cervical vertebrae, granulomatous and/or pyogranulomatous lesions were found in the adjacent soft tissues around these vertebrae and in the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, femoral bone marrow, and left eye. Acid-fast stains were then performed and revealed low numbers of intracellular and extracellular acid-fast bacteria within the lungs, liver, cervical bone marrow, and skin overlying the cervical vertebrae.

This macaque had repeatedly tested negative for tuberculosis using intradermal tuberculin. The most recent test had been administered approximately 3.5 months before the monkey was euthanized. However, based on the histologic findings, a mycobacterial infection was strongly suspected. Unfortunately, there were no fresh tissue samples available then for microbial culture. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples of lung were submitted to the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa for testing by PCR and these results were positive for organisms in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex but negative for organisms in the Mycobacterium avium complex (A. Lehmkuhl, pers. comm.).

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex consists of several species of closely related bacteria in the genus Mycobacterium, including M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. caprae, and M. microti. The Mycobacterium avium complex includes M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. chimera. The causative agent of Johne's disease in ruminants is currently classified as a subspecies of M. avium (i.e. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis).

Immunofluorescence assays were then performed "in-house" at USAMRIID on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections of lung using a commercially-available rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam ab43019) that specifically detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen "Ag85B". Low numbers of immunofluorescent bacteria were detected in the lung granulomas.

Based on the test results, we concluded that this monkey was infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis rather than another bacterial species in this "complex". Follow-up surveillance and testing of other macaques that had been exposed to this index case revealed additional affected animals and some of these have been culture-positive for M. tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis in humans (and macaques) is usually caused by M. tuberculosis although infection with M. bovis in humans was also common before pasteurization of milk as well as testing and culling of TB-positive dairy cows became standard practices.4 Human tuberculosis is primarily a disease of the respiratory tract.4 However, secondary infection of vertebrae can occur due to direct spread from the thorax or as a sequela to bacteremia.3,4,6 The thoracic vertebrae are most commonly affected, with lumbar and/or cervical vertebrae less commonly affected.3 Cases of spinal tuberculosis were described in detail in a 1779 publication by Sir Percival Pott.1 Consequently, spinal tuberculosis in humans became known as "Pott Disease" or "Pott's Disease".2-4,6 Another common term for this condition is tuberculous spondylitis.3 The chronic osteomyelitis often results in destruction and collapse of vertebral bodies causing spinal cord damage and neurologic signs ("Pott's paraplegia").2,3 It is interesting to note that the initial clinical signs that this cynomolgus macaque presented were weakness and movement difficulties involving its left arm and left leg.

Deformation of the spinal column in chronic cases of Pott's Disease often caused affected humans to have a "hunchback" appearance.2,3 It is believed that observing victims of Pott's Disease inspired Victor Hugo to create the character of "Quasimodo" for his novel "The Hunchback of Notre Dame".6

Note: Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

Contributing Institution:

U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID)

Pathology Division

1425 Porter Street

Fort Detrick, MD 21702-5011.

http://www.usamriid.army.mil/

JPC Diagnosis:

Cervical vertebrae: Discospondylitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, marked, with periosteal new bone formation.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of spinal tuberculosis, which represents 1-2% of all tuberculosis cases in humans and is the most common site of musculoskeletal infection with this entity. Although Pott described the manifestations of spinal tuberculosis in 1779, it has been identified in Egyptian mummies dated before 3300 BC, making it one of the oldest diseases known. Despite being an ancient disease, tuberculosis continues to be a significant public health issue with 10.4 million new cases reported worldwide in 2015. In regard to spinal tuberculosis specifically, the highest incidence is in impoverished populations, most commonly affecting young adults and children. Another significant risk factor for tuberculosis is HIV co-infection, which results in suppression of CD4+ lymphocytes and degraded cellular immunity. In addition, Chinese patients with the FokI polymorphism in the vitamin-D receptor gene are predisposed to spinal tuberculosis.1

M. tuberculosis is readily phagocytized by macrophages once it enters the body, where it is resistant to intracellular digestion by preventing phagosome-lysosome fusion. This feat is accomplished by recruiting a host protein known as coronin, which prevents fusion of these organelles by activating phosphatase calcineurin. The organism then replicates within macrophages until pattern recognition receptors, such as TLR2 and TLR9, bind substances such as mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan and unmethylated CpG nucleotides. This in turn initiates a Th1 inflammatory response, which most notably results in the production of IFN-γ by CD4+ lymphocytes. IFN-γ is essential for the containment of M. tuberculosis for multiple reasons, including 1) stimulation of phagolysosome maturation in infected macrophages, 2) stimulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase, resulting in the creation of reactive nitrogen intermediates, 3) mobilization of antimicrobial peptides (defensins), and 4) stimulation of increased autophagy, which is essential for the destruction of intracellular bacteria.4

As noted by the contributor, the M. tuberculosis may disseminate to the vertebrae by either direct or hematogenous routes. Vertebrae are particularly vulnerable to the latter due to the presence of rich vascular plexuses formed in the subchondral regions supplied by the posterior and anterior spinal arteries. The osteomyelitis that occurs following colonization initially causes paradiscal destruction of the vertebral body; the disc typically remains intact until late in the disease process. Neurologic sequlae typically manifest late in the disease process, as the result of spinal compression secondary to kyphosis in addition to epidural pus and disc and osseous debris.1

Vertebral infections are typically insidious and progress over four to 11 months, with weight loss being the most common clinical sign, followed by fatigue, pyrexia, night sweats, and pain. Neurologic deficits are also common, particularly when cervical or thoracic vertebral regions are affected.1

In humans, spinal tuberculosis infections are typically paucibacillary, with acid fast bacilli observed in only 38% of biopsies in one report. Histologic features such as caseating granulomas and giant cells are often considered diagnostic in endemic regions, although similar lesions also occur with conditions such as sarcoidosis and cat scratch disease (Bartonella henselae). Mycobacterium tuberculosis can be identified with a specificity of 80-90% and sensitivity of 95% using PCR technology. However, this technology is not readily accessible in socioeconomically deprived communities with poor access to healthcare.1

In regard to non-human primates (NHPs), tuberculosis is rare in wild populations living in isolation from human contact. However, it is also the most common reported infectious disease of captive NHPs. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is typically introduced to a naïve NHP population following an exposure to an infected human, most commonly via inhalation. Following its introduction to a previously naïve population, the pathogen undergoes monkey-to-monkey transmission, predominantly via aerosol and occasionally ingestion.5

Rhesus macaques are quite sensitive to M. tuberculosis and develop a variety of lesions similar to those reported in humans. Tuberculosis also tends to be rapidly progressive in this species, which can lead to widespread dissemination within a colony. In addition, surveillance testing utilizing the traditional intradermal tuberculin skin testing method is associated with both false positives and negatives (such as in this case); therefore additional testing methods should be considered.5

According to the WHO, 80% of human tuberculosis cases occur in 22 countries. Two countries on this list include India and China, which both export large numbers of NHPs. Therefore, it is likely many NHPs become infected by caretakers or during the subsequent international trade process prior to their arrival at their final destination.5

Conference participants discussed use of the terms 'osteomyelitis' and 'discospondylitis' while determining how to best characterize the lesion in this case. Osteomyelitis is defined as inflammation of the bone and marrow while discospondylitis is defined as inflammation of the intervertebral disk as well as the adjacent vertebrae. Given the previously discussed pathogenesis of spinal tuberculosis, this lesion most likely originated as an osteomyelitis. However, due to involvement of the intervertebral disk, as evidenced by extruded basophilic material consistent with nucleus pulposus, the majority of participants favored discospondylitis.

References:

1. Dunn RN, Ben Husien M. Spinal tuberculosis: review of current management. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(4):425-431.

2. Garg RV, Somvanshi DS. Spinal tuberculosis: a review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011; 34(5):440-454.

3. Hoch BL, Klein MJ, Schiller AL. Bones and Joints. In: Rubin R, Strayer DS, eds. Rubin's Pathology: Clinicopathologigic Foundations of Medicine 5th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1083-1151.

4. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease 9th Ed. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

5. Mätz-Rensing K, Hartmann T, Wendel GM, et al. Outbreak of Tuberculosis in a Colony of Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca mulatta) after Possible Indirect Contact with a Human TB Patient. J Comp Pathol. 2015;153(2-3):81-91.

6. Rosenberg AE. Bones, Joints, and Soft Tissue Tumors. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC eds. Robbins Basic Pathology 9th Ed. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier Saunders; 2013:774.