CASE III:

Signalment:

Age unknown, adult male octopus (Octopus vulgaris)

History:

An experimentally naïve octopus was found dead in the morning. The animal was caught from the shores of the Florida Keys and had been doing well for up to a month when it started displaying periods of lethargy and decreased appetite. One night, the animal went into one of its tunnels and never re-emerged. Water quality parameters were within normal limits during this period.

Gross Pathology:

A dead, frozen male octopus with mottled pale brown to gray skin was received for examination in severely autolyzed post-mortem condition. The skin had numerous foci of subtle white discoloration.

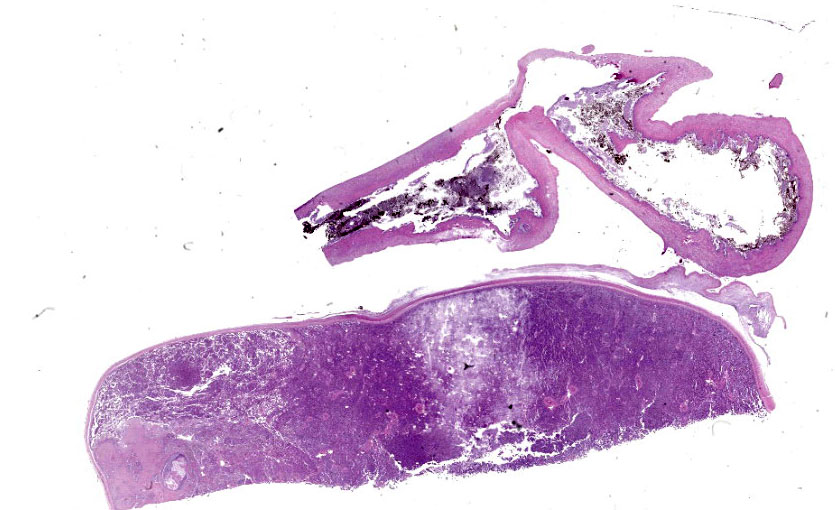

Microscopic Description:

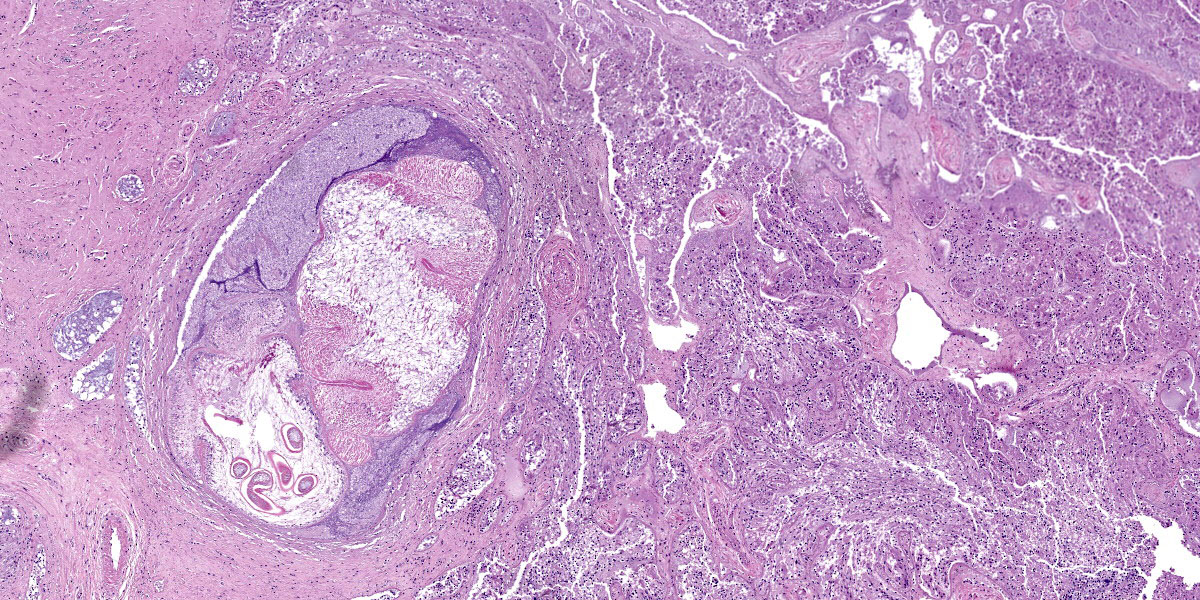

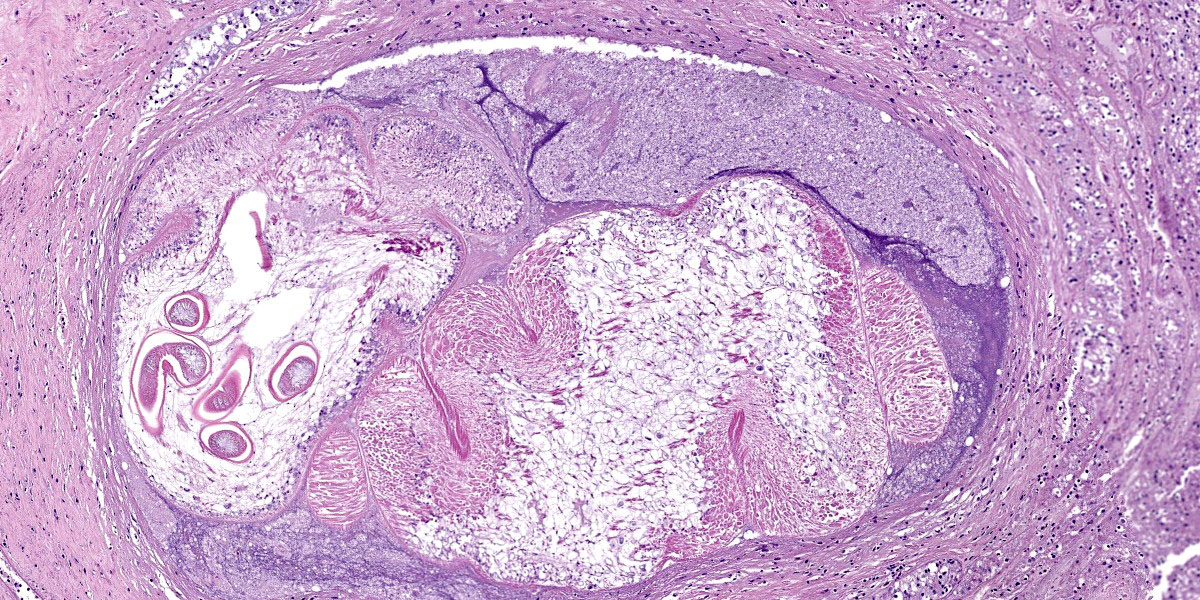

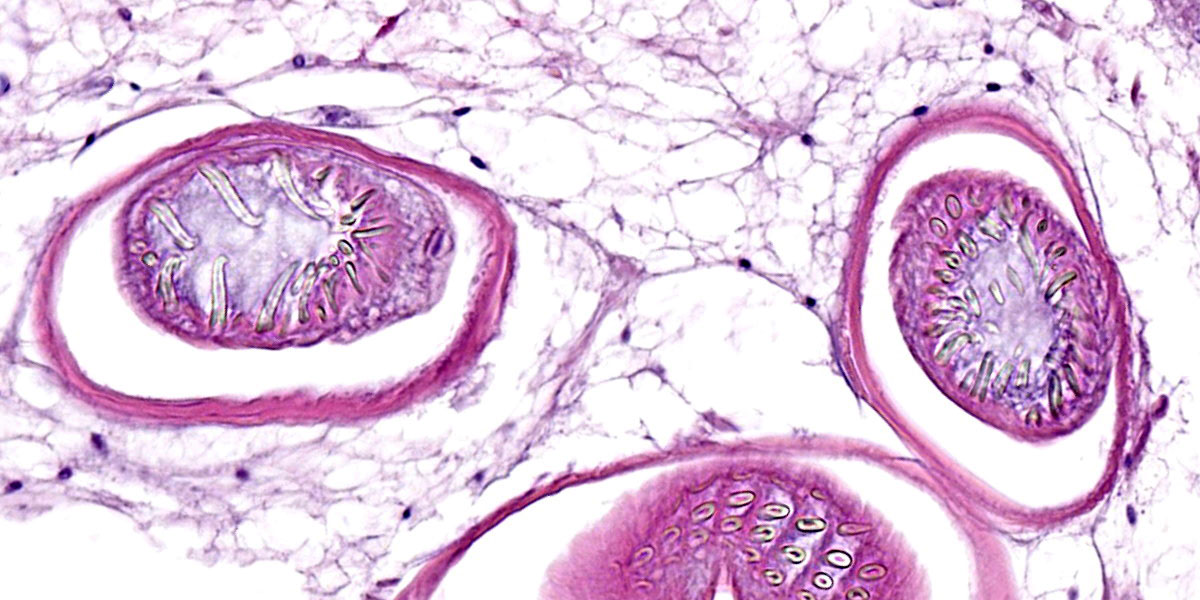

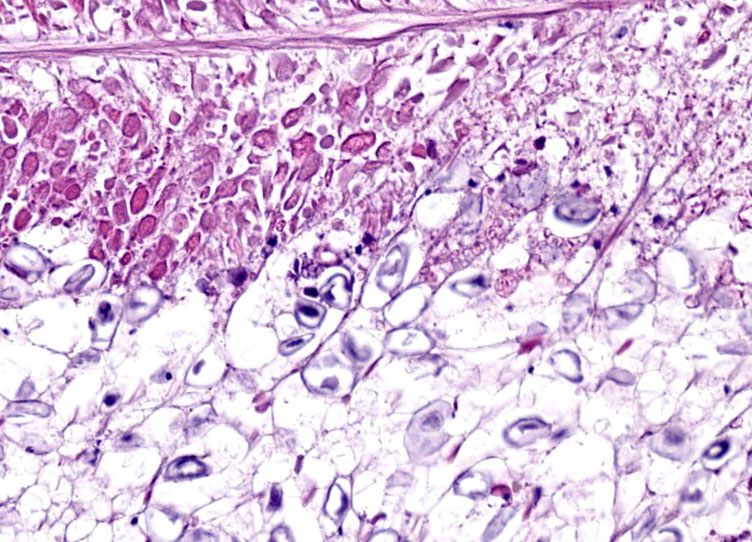

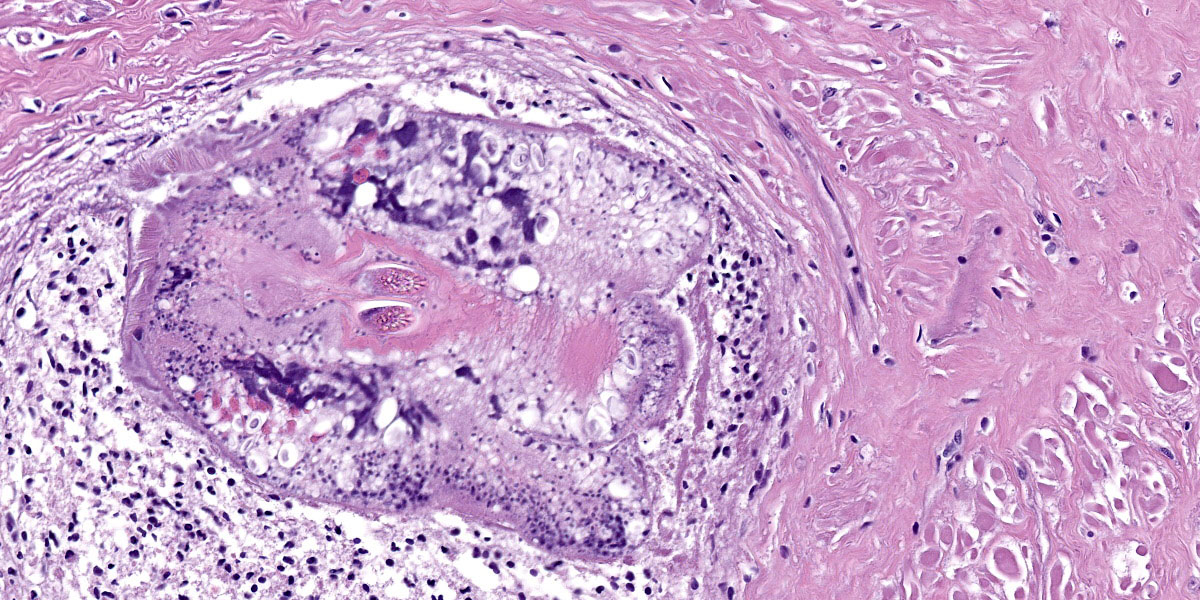

Digestive gland: Approximately 20% of the digestive gland mucosa is effaced by multifocal to coalescing nodules of fibrosis, necrosis, and inflammation centered around cestode larvae of up to 650 µm in diameter, with a 4-6 µm thick, homogeneous, eosinophilic tegument, spongy parenchyma, numerous peripheral calcareous corpuscles, suckers, and bilaterally symmetrical bothria with multiple tentacles that were anchored by prominent bulbs encircled by striated retractor muscles that attached to everted or invaginated hooks. Confident assessment of mucosal and cellular details is hampered by a high degree of postmortem autolysis and freeze-thaw artifacts.

Esophagus: Occasionally within the lumen or embedded in the esophageal wall are cestode larvae with similar features as previously described.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Digestive gland and esophagus: Moderate, multifocal to coalescing, chronic cestodiasis, with hemocytic infiltrates, necrosis, and fibrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Despite the severe degree of postmortem autolytic and freeze-thaw artifacts, this octopus had unequivocal cestodiasis in the digestive tract, widespread coccidiosis in all examined skin tissues (including arms, funnel, and dorsal mantle), eyes, and gills, consistent with Aggregata spp. infection, and varying degrees of systemic hemocyte infiltration throughout the body.

Cestodiasis in cephalopods is common, and many cephalopod species serve as intermediate or paratenic hosts and act as vectors for other intermediate or definitive hosts. Adult cestodes are not frequently reported, but the diversity of larval and post-larval stages found in cephalopods suggests that they are important intermediate hosts for the development of adult stages that parasitize cartilaginous and bony fish. In cephalopods, larval cestodes most often infect the digestive tract, but may be found free in the mantle cavity or encysted within the mantle musculature. The most commonly reported cestode to infect cephalopods is Phyllobothrium spp, but cestodes from other genera have also been identified in the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) and include the onchoproteocephalidean Acanthobothrium spp, the tetraphyllidean Anthobothrium spp, and the trypanorhynch Nybelinia spp. Adult stages of Tetraphyllidea and Trypanorhynchea are found within the gastrointestinal tract of sharks, skates, and rays, and their larval forms are some of the most commonly identified cestodes in cephalopods.3

Coccidiosis is a common, chronic disease in cephalopods, caused by an obligate, intracellular protozoa in the phylum Apicomplexa, family Aggregatidae. To date, 10 species have been described worldwide in octopus, squid, and cuttlefish. All 10 species are considered pathogenic. This disease primarily affects the digestive tract of cephalopods, but extraintestinal coccidiosis, as seen in this case, have been reported when it harbors an intense infection. Damage to the host includes mechanical, biochemical, and molecular effects, and infection severely weakens the host’s innate immunity making it vulnerable to secondary infections. Notable signs of disease include malabsorption syndrome, decrease in the number of hemocytes, plasmatic protein, and iron in hemolymph, as well as up- regulation of immune genes.1

Senescence can also cause immunosuppression and make the octopus more susceptible to secondary diseases. This octopus also had evidence of cataract in one eye, similar to what has been described in the literature, in

which possible underlying causes for the intraocular lesions included water quality, ocular manifestation of a systemic disease, intraocular infection, or natural senescence. Senescence is a natural pre-death process in octopuses and other species. While senescence is not a disease or a result of illness, diseases can be a symptom of senescence. Clinical signs of senescence in octopuses are observed over a couple of months and are reported to include loss of appetite, weight loss, retraction of skin around the eyes, uncoordinated movements, and increased undirected activity level. In octopuses, senescence-like symptoms can also be triggered by collection stress, systemic diseases, and improper water temperature or water quality.

Octopuses lack a humoral immune system, and their innate immune system with cellular factors is their primary mechanism of defense against disease. The octopus' hemocytes respond to infection with phagocyntesis, encapsulation, infiltration or cytotoxicity, aiming to destroy or isolate pathogens.2 In summary, senescence and/or stress may have facilitated parasitic burden, inflammation, other infectious processes, and potential sepsis as contributory factors to the demise of this octopus.

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Comparative Pathology

(Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, The Rockefeller University, and Weill Cornell Medicine)

http://www.mskcc.org/research/comparative-medicine-pathology-

JPC Diagnoses:

- Digestive gland and esophagus: Larval cestodes, multiple, with fibrosis and hemocytic inflammation.

- Digestive gland: Atrophy, diffuse, moderate.

JPC Comment:

This case provides an excellent example of cestodiasis in an unusual species, and the contributor provides a good summary of the histologic lesions that typify cestode infections in cephalopods.

An additional finding in this case was atrophy of the digestive gland, the histologic correlate for which is loss of eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules. Although this is a common lesion in senescence, it can be observed in any animal with negative energy balance.

In this case, the reported severe coccidiosis and resultant malabsorption likely led to negative energy balance and digestive gland atrophy. While infections are reportedly more common and more abundant in senescent animals, the primary lesion of senescence is gonadal atrophy.4

Coccidia were not observed in the examined slide, which included esophagus and digestive gland. While the gills and the intestines are commonly infected, esophagus and digestive gland can be infected with coccidia in severe cases. Of all cephalopod species, common octopuses are one of the most commonly infected with Aggregata spp.

Conference discussion was facilitated by JPC’s very own Dr. Elise LaDouceur, who discussed cephalopod anatomy generally, before diving into the histologic lesions. The digestive gland is analogous to the mammalian liver and the normally abundant eosinophilic globules within the digestive gland are typically packed with storage products such as glycogen and lipid. Dr. LaDouceur noted that the digestive gland was extremely autolyzed, but despite the autolysis, the lack of eosinophilic globules within the digestive gland was notable. This led to a discussion of senescence, a feature of many invertebrates’ life history, where metabolism is shut down after release of gonads.

Conference participants discussed the large cestode larvae within the digestive gland and the accompanying multifocal areas of necrosis in the adjacent parenchyma, interpreted as migration tracts. Dr. Gardiner believed the organism to be an encysted cestode, which would typically grow in place without moving through the tissue, and questioned whether the histologic features represented true migration tracts. These histologic features do, however, align with recent published reports in cephalopods that feature cestodes invading tissues of organs with non-chitinized epithelium, leaving behind trailing necrotic foci.

Finally, Dr. LaDouceur pointed conference participants to an excellent, open-source resource by Gestal, et al (see reference below), which provides excellent gross and histologic images of common cephalopod pathogens, along with discussion of the unique biology of these interesting Molluscans.

References:

- Castellanos-Martínez S, Gestal C, Pascual S, Mladineo I, Azevedo C. Protist (Coccidia) and related diseases. In: Gestal C, Pascual S, Guerra Á, Fiorito G, Vieites J, eds. Handbook of pathogens and diseases in Cephalopods. Springer; 2019:143-152.

- de Linde Henriksen M, Ofri R, Shomrat T, et al. Ocular anatomy and correlation with histopathologic findings in two common octopuses (Octopus vulgaris) and one giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) diagnosed with inflammatory phakitis and retinitis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2021;24(3):218-228.

- Finnegan DK, Murray MJ, Young S, Garner MM, LaDouceur EEB. Histologic lesions of cestodiasis in octopuses. Vet Pathol. 2023;60(5):599-604.

- Gestal C, Pascual S, Guerra Á, Fiorito G, Vieites J, eds. Handbook of Pathogens and Diseases in Cephalopods. Springer; 2019. Available at: https://link.springer. com/book/ 10.1007/ 978-3-030-11330-8.

- Rich AF, Denk D, Sangster CR, Stidworthy MF. A retrospective study of pathologic findings in cephalopods (extant subclasses: Coleoidea and Nautiloidea) under laboratory and aquarium management. Vet Pathol. 2023;60(5):578-598.