Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 18

February 7th, 2018

CASE IV: S 504/16 (JPC 4102124)

Signalment: 6-year-old, female, Warmblood (Equus ferus caballus), equine.

History: Severe, subcutaneous edema affected all four limbs, the ventral abdomen, and the head. Multifocal petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages were visible on all mucous membranes including the mouth and the vagina. The rectal temperature was 39.7°C (reference interval 37,0 – 38,0°C) and white blood cell count was elevated (15.7 x 109/l, reference value 5 – 10 x 109/l). The horse was treated with antibiotics, flunixin (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) and high dosages of dexamethasone. The horse rapidly deteriorated and was humanely euthanized upon the owner’s request.

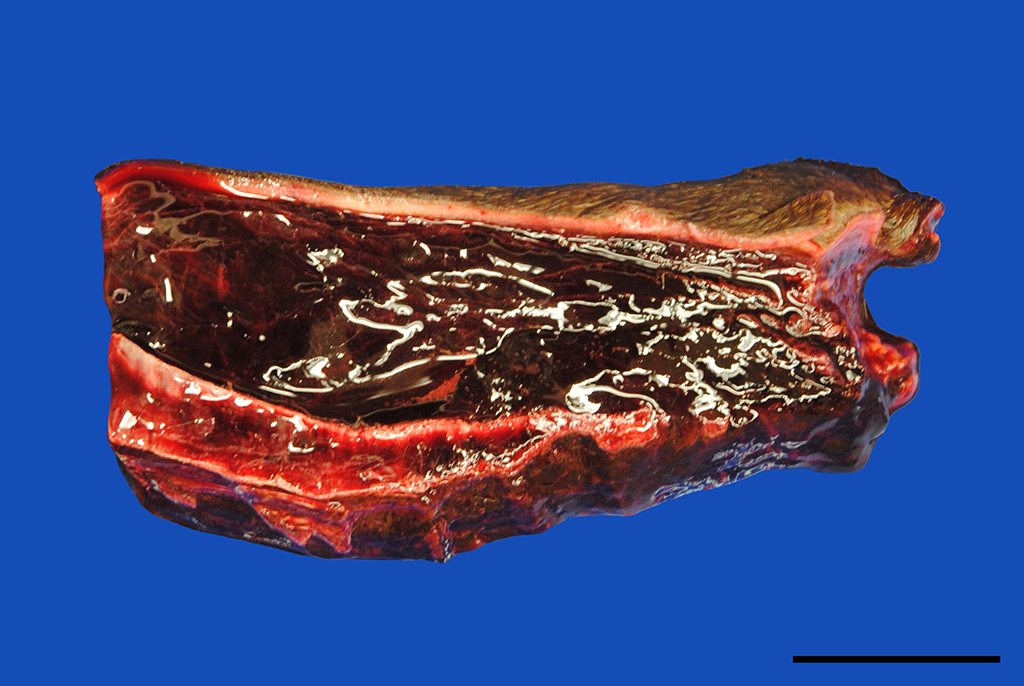

Gross Pathology: In addition to the mucous membranes, petechial to ecchymotic hemorrhages were striking in the parietal and visceral pleura, the lung, myo- and pericardium as well as the mediastinum. Small proportions of pus drained from the cut surface of the right retropharyngeal lymph node. The subcutis of the ventral body parts including the legs, ventral abdomen and scrotum was severely thickened up to 5 cm by edema.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

Streptococcus equi ssp. equi was isolated from the right retropharyngeal lymph node.

Microscopic Description:

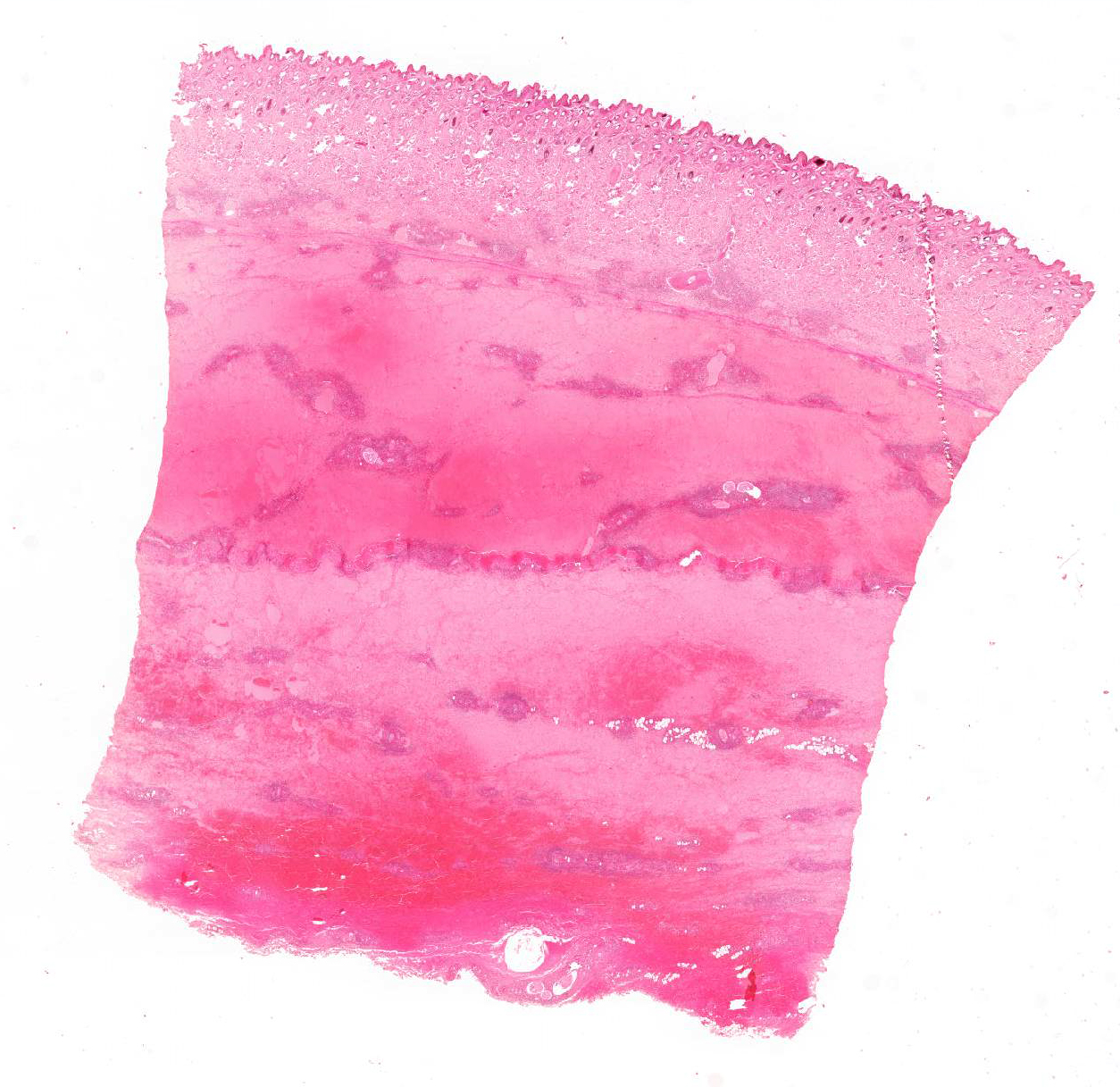

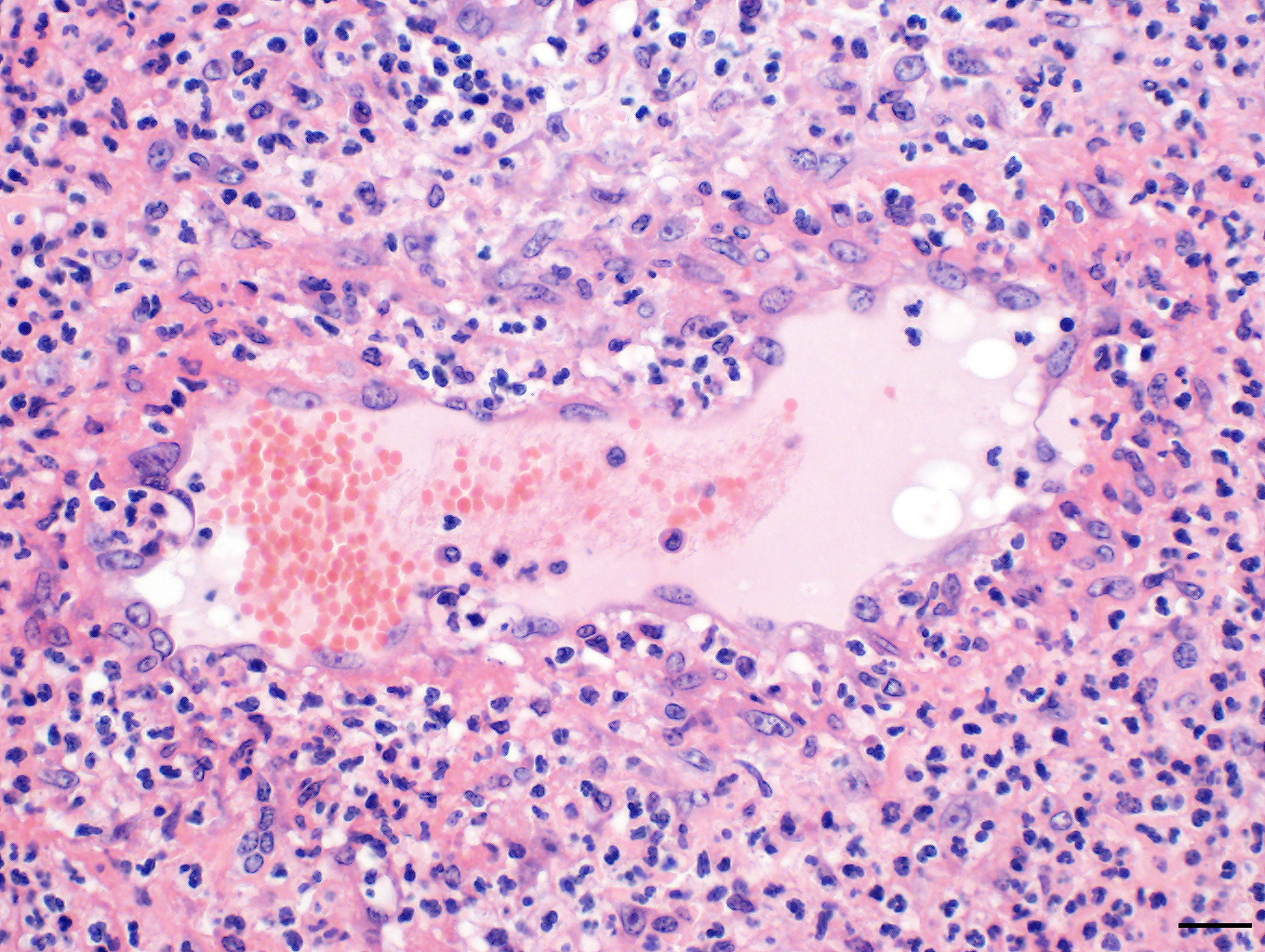

Skin: The subcutis is severely thickened by a mainly homogenous and partially fibrillary pale eosinophilic material, clear space (edema) and extravascular erythrocytes (acute hemorrhages). Surrounding blood vessels, high numbers of leukocytes are present, predominantly degenerate neutrophils and fewer numbers of macrophages. Almost all blood vessels are multifocally disrupted and expanded by moderate deposition of a loosely arranged eosinophilic homogenous to fibrillar material (fibrin) admixed with few degenerate neutrophils and cellular and karyorrhectic debris (fibrinoid necrosis). The endothelial lining is partially lost or endothelium cell nuclei are prominent and oval in shape (endothelial activation). The fibrinoid necrosis of the blood vessels and the perivascular infiltration expand into the surrounding dermis. The epidermis is normal.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Skin, subcutis: Vasculitis, severe, acute, diffuse, leukocytoclastic with severe edema, multifocal hemorrhage and dermal necrosis.

Contributor’s Comment: The syndrome purpura hemorrhagica, formerly known as morbus maculosus equorum, is consistent with a generalized leukocytoclastic vasculitis almost always including the skin.14 It is clinically characterized by subcutaneous edema of ventral body parts and petechial or ecchymotic hemorrhages in the visible mucous membranes, i.e mouth and vagina. Underlying hemorrhagic diathesis is caused by endothelial and / or vascular damage in context of a generalized vasculitis. The latter is considered to result from a type III hypersensitivity with deposition of antigen-antibody immune-complexes in blood vessel walls. Activation of complement components and a subsequent recruitment and activation of leukocytes is responsible for the damage of the blood vessels. Considering the pathogenesis, the syndrome is not primarily caused by a specific infectious agent and hence not transmissible. However, in most cases, a previous infection provokes the hypersensitivity reaction. Most commonly, as in the current case, a preceding infection with Streptococcus equi spp. equi (Strangles) can be referred as the initiating cause of purpura hemorrhagica. It has been detected in approximately 5.4 to 6.5% of the infected horses, typically 2 to 4 weeks post infection.4,14 Although the pathogenesis of Streptococcus equi spp. equi associated purpura hemorrhagica is not fully understood, high serum concentrations of IgA antibodies and low serum concentrations of IgG antibodies seem to favor the development of immune complexes on the basis of the M-like protein of Streptococcus equi (SeM).14 Vaccination with SeM may trigger purpura hemorrhagica.6 Furthermore, additional infectious agents are discussed as possible cause of this syndrome including viruses (equine influenza virus, equine herpes viruses, equine arteritis virus) and bacteria (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, Streptococcus equi spp. zooepidemicus, Rhodococcus equi).2,11,16

Purpura hemorrhagica, i.e, a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, may be diagnosed antemortem by full-thickness punch skin biopsies.11,16 However, biopsies should be taken prior to treatment with corticosteroids as these may tremendously reduce the severity of the vasculitis and even suppress any histological evidence whatsoever.11

The prognosis of purpura hemorrhagica is difficult to predict, however may be favorable with an immediate and aggressive therapy including immunosuppression with corticosteroids.6 Complications like laryngeal edema (dyspnea), dermal necrosis, thrombophlebitis, glomerulonephritis, and infarctions of skeletal musculature, lung, skin and the intestinal tract as well as colic due to severe edema, gastric rupture, intestinal intussusception, torsion and prolapse recti, may occur.5,8,9,13,14

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin and dermis: Vasculitis, necrotizing, diffuse, severe with marked hemorrhage, edema, and moderate neutrophilic dermatitis and cellulitis, Warmblood (Equus ferus caballus), equine.

Conference Comment: Purpura hemorrhagica (from the Latin meaning “purple”) is a type of immune-mediated vasculitis characterized grossly as red or purple areas of hemorrhage of the skin and mucus membranes with subsequent edema. Microscopically, affected vessels are surrounded by neutrophils that cause destruction of vascular walls (leukocytoclastic vasculitis), perivascular edema, hemorrhage, and fibrin. Commonly associated with previous infection with Streptococcus equi (usually involving the respiratory tract with abscessation), Corynebacteirum pseudotuberculosis, or vaccination with S. equi M protein (SeM); purpura hemorrhagica is classified as a type III hypersensitivity reaction and is caused by immune complexes (antigen and immunoglobulins) that deposit on the walls of small blood vessels (resulting in vasculitis) or renal glomerular capillaries and vessels (resulting in glomerulonephritis).6,7,12

Clinically, edema is well-demarcated and most often noticed in the distal limbs, followed by the ventrum and head with fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, anorexia, and depression. Clinical signs vary based on the organ system involved and can include all of the following: colic, lameness, neurologic signs, renal dysfunction, small intestinal intussusceptions, and muscular infarcts. Clinical pathology abnormalities include: leukopenia or leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased acute phase proteins, and increased muscle enzyme activities. Diagnosis is based on a combination of history, clinical signs, antibody titers (very high Se-M specific titers), and skin biopsies (to confirm leukocytoclastic vasculitis). Treatment is based on supportive care, immune suppression, and removal of the underlying cause.6,12

Differentials for purpura hemorrhagica include endotheliotropic viruses such as: equine viral arteritis, African horse sickness (Orbivirus), Hendra virus, or equine herpesvirus-1. Equine viral arteritis virus, an Arterivirus, is transmitted in contaminated body fluids via venereal or respiratory routes. The virus targets mononuclear and endothelial cells; clinical signs are usually associated with vasculitis. Clinical signs include: fever, leukopenia, depression, periorbital and supraorbital edema, conjunctivitis, lacrimation, petechiae, respiratory signs, colic or diarrhea, and abortion.6 African horse sickness (AHS) is a foreign animal disease (never currently been reported in the United States) that results in edema, predominately of the nuchal ligament and supraorbital fossa, pulmonary edema, and myocardial failure. Equine Orbivirus is transmitted by Culicoides imicola and is endotheliotropic (related to the causative agent of bluetongue). In Africa, all equids are susceptible, with horses being the most susceptible, followed by mules, donkeys, and zebras. Hendra virus causes fatal pneumonia, encephalitis, and rarely subcutaneous edema in horses and humans (zoonotic).3 Finally, equine herpesvirus-1, though most often associated with the central nervous system, is also an endotheliotropic virus and with chronicity rarely causes petechial hemorrhage and edema in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues.1

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Freie Universitaet Berlin

http://www.vetmed.fu-berlin.de/en/einrichtungen/institute/we12/index.html

References:

- Aleman M, Nout-Lomas YS, Reed SM. Disorders of the neurologic system. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018:645-652.

- Aleman M, Spier SJ, Wilson WD, Doherr M. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in horses: 538 cases (1982-1993). JAVMA. 1996;209:804-809.

- Davis E. Disorders of the respiratory system. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018:345-346.

- Duffee LR, Stefanovski D, Boston RC, Boyle AG. Predictor variables for and complications associated with Streptococcus equi subsp equi infection in horses. JAVMA. 2015;247:1161-1168.

- Dujardin C. Multiple small-intestine intussusceptions: a complication of purpura haemorrhagica in a horse. Tijdschrift voor diergeneeskunde. 2011;136:422-426.

- Dunkel B. Disorders of the hematopoietic system. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018:1011,1012.

- Hargis AM, Myers S. The integument. In: Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:1120-1121.

- Jaeschke G, Wintzer H. Ein Beitrag zum Krankheitsbild des Morbus maculosus equorum. Tieraerztliche Praxis. 1988:385-394.

- Kaese HJ, Valberg SJ, Hayden DW, Wilson JH, Charlton P, Ames TR, Al-Ghamdi GM. Infarctive purpura hemorrhagica in five horses. JAVMA. 2005;226:1893-1898.

- Mealey RH, Long MT. Mechanisms of disease and immunity. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018:46.

- Pusterla N, Watson JL, Affolter VK, Magdesian K, Wilson W, Carlson G. Purpura haemorrhagica in 53 horses. The Veterinary Record. 2003;153:118-121.

- Rashmir-Raven AM. Disorders of the skin. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine. 4th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018:1196.

- Roberts M, Kelly W. Renal dysfunction in a case of purpura haemorrhagica in a horse. The Veterinary Record. 1982;110:144-146.

- Sweeney C, Whitlock R, Meirs D, Whitehead S, Barningham S. Complications associated with Streptococcus equi infection on a horse farm. JAVMA. 1987;191:1446-1448.

- Sweeney CR, Timoney JF, Newton JR, Hines MT. Streptococcus equi infections in horses: guidelines for treatment, control, and prevention of strangles. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2005;19:123-134.

- Wiedner EB, Couëtil LL, Levy M, Sojka JE. Purpura hemorrhagica. Comp Clin Educ Practicing Vet – Equine Ed. 2006;1(2):82-93.