WSC 2023-2024, Conference 15, Case 1

Signalment:

Four-year-old, male neutered Pygmy goat (Capra aegagrus hircus)

History:

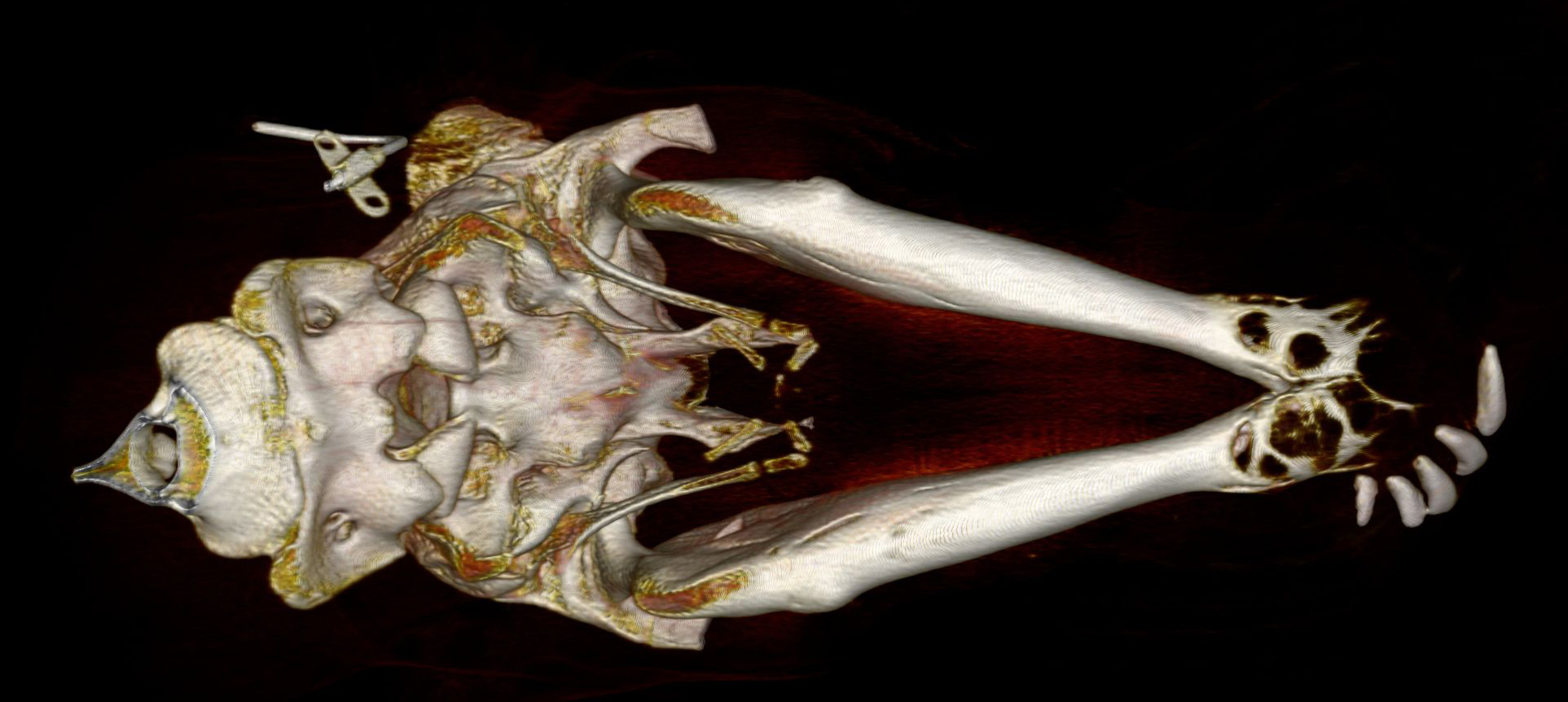

This pygmy goat was presented to the Royal Veterinary College Farm Animal Hospital for further evaluation and possible treatment of an oral mass. Computed tomography (CT) of the head identified severe bony enlargement of the rostral aspect of both mandibles with destructive and lytic bony changes from the rostral margins of the mandible up to the first premolar bilaterally. Moderate soft tissue swelling surrounded the misshaped mandibles. The 402, 403, and 404 teeth were missing and the remaining incisors were displaced laterally. Surgical options were discussed with the owner but due to the extent of the lesion and the complexity of the surgical approach, the owner elected to euthanise the animal.

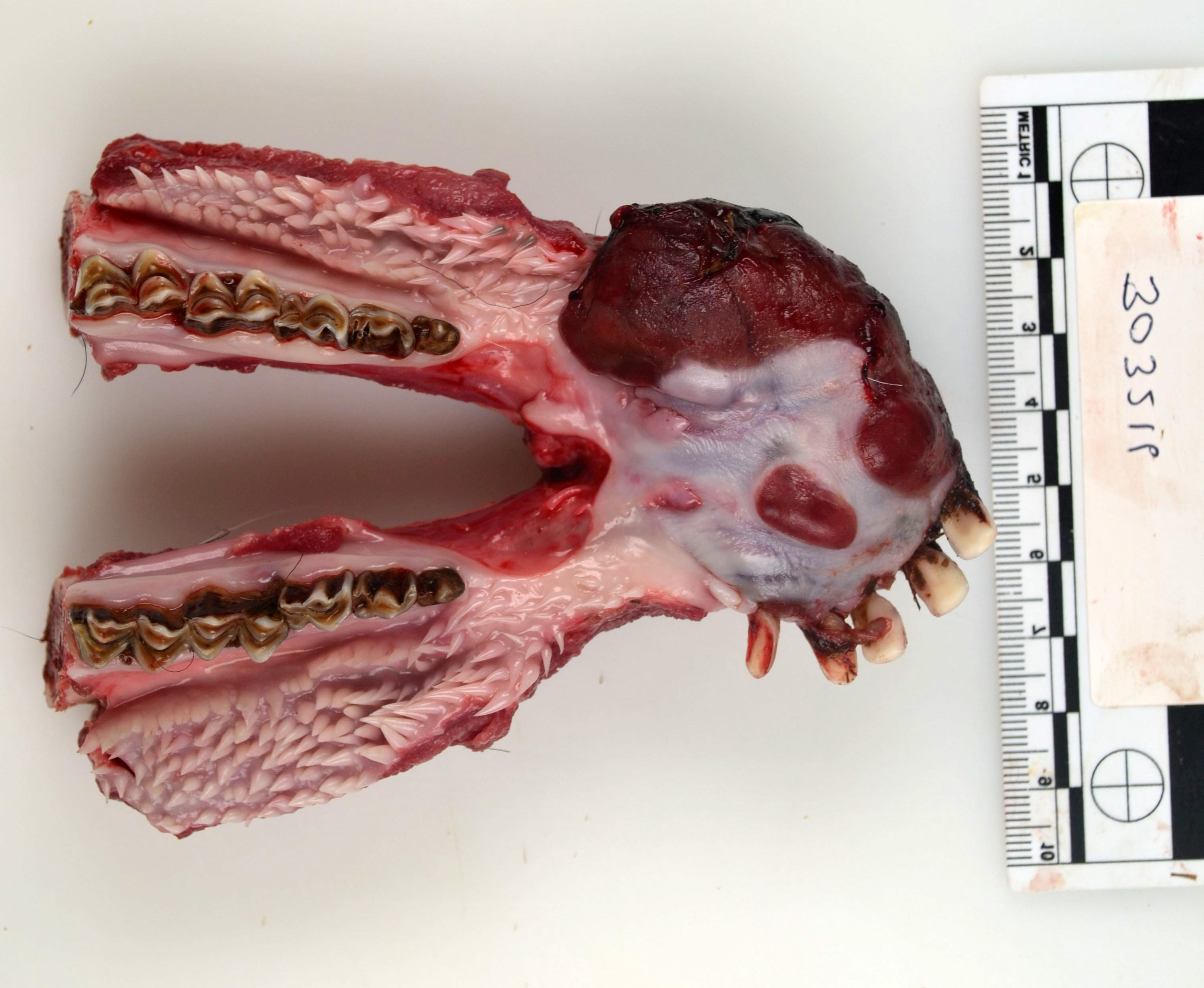

Gross Pathology:

Arising from the rostral mandible predominantly to the right of midline is a proliferative, dark red, moderately soft mass measuring 8x3x2.5cm with a bleeding surface. On sectioning, the mass is grey and solid. The mass displaces the five remaining incisors over to the left side and all the incisors are loose.

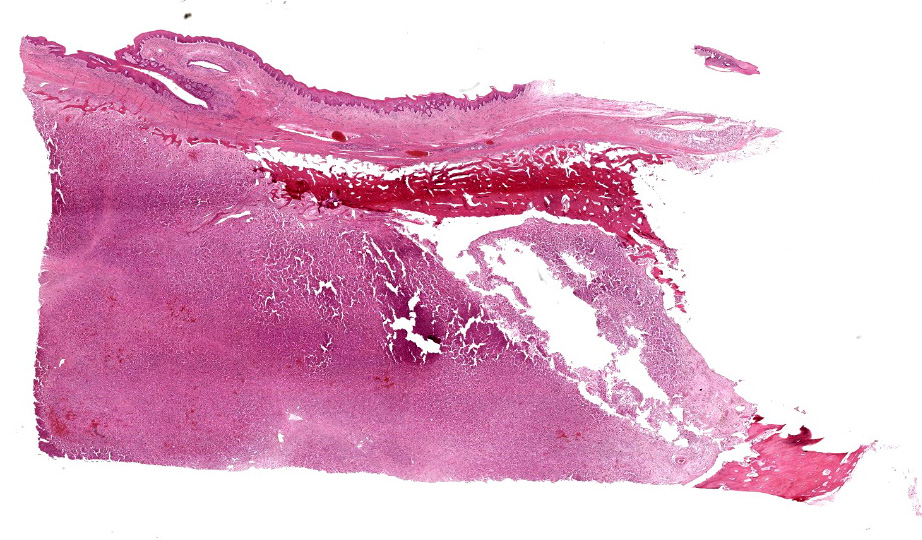

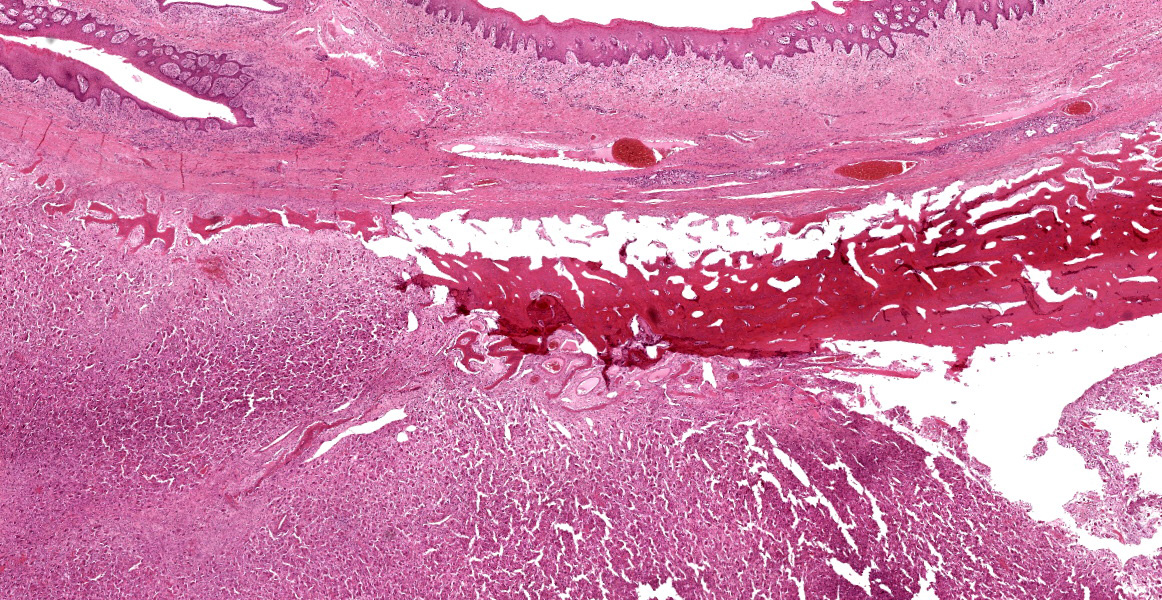

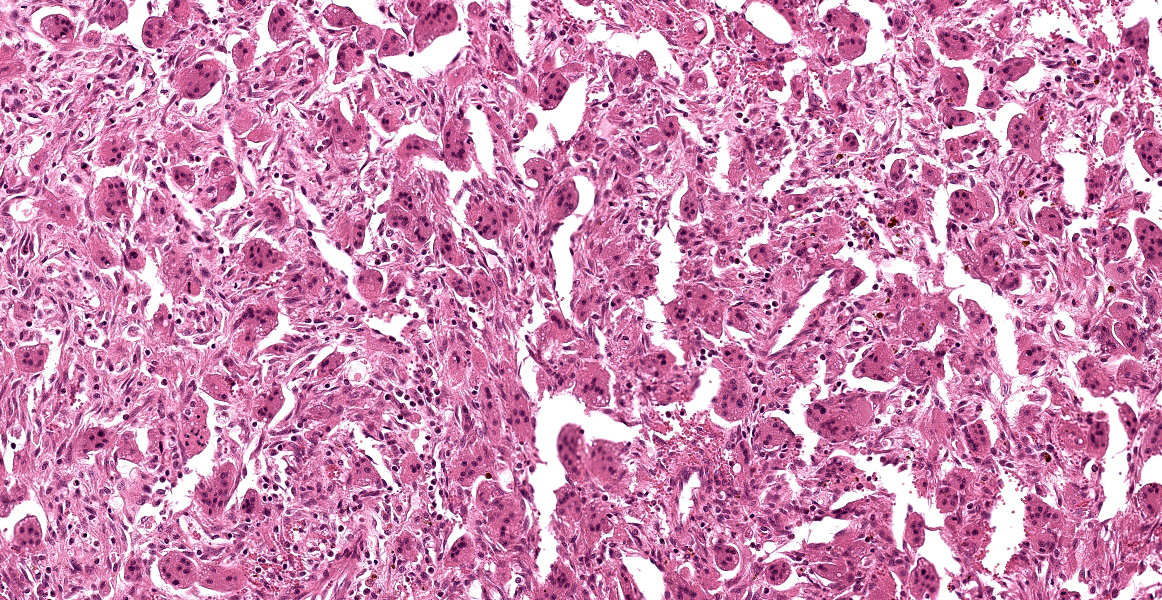

Microscopic Description:

Rostral mandibular mass: Arising within the mandibular bone is an unencapsulated, moderately well demarcated, expansile, multinodular neoplasm which raises the contour of the gingival epithelium. The mass is composed of abundant multinucleated giant cells interspersed with a dense population of spindle shaped cells in a fibrovascular stroma. Each cell type represents approximately 50% of the cellular population in the section. The giant cells have well demarcated borders with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm that contains varying numbers of microvacuoles, and between two and ten nuclei which are randomly distributed in the centre of the cell and have finely stippled chromatin. The spindle-shaped cells are poorly defined with a moderate amount of eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm, elongate nuclei, and finely clumped chromatin. There is mild anisokaryosis and anisocytosis of both cellular populations. There are four mitoses detected in 10 HPF’s (x400), three of which are bizarre mitoses. At the periphery of the neoplasm, there is fragmentation and necrosis of the mandibular bone and hyperplasia of osteoblasts. Occasional giant cells contain multiple pyknotic nuclei (apoptosis or individual cell necrosis). Multifocally, macrophages contain yellow to brown, globular pigment (haemosiderophages). The overlying gingival epithelium exhibits mild hyperplasia.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mandible: Central giant cell granuloma (aggressive form).

Contributor’s Comment:

Differential diagnoses for masses arising in the jaw which contain numerous giant cells include giant cell granulomas of the jaws, osteosarcoma (giant cell variant), osseous fibroma, or low grade spindle cell sarcoma with giant cells. The density of the giant cell population and the lack of osteoid or mineralized matrix is not consistent with the latter three differentials in this case.

Giant cell granulomas of the jaws are currently differentiated based on location into peripheral or central giant cell granulomas.10 Peripheral giant cell granuloma (PGCG, previously known as giant cell epulis, peripheral giant cell tumor, osteoclastoma, reparatory giant cell granuloma, and giant cell hyperplasia of the oral mucosa) is a reactive and non-neoplastic gingival lesion that clinically presents as a soft to firm, polypoid or nodular lesion on the gingiva and alveolar ridge and is believed to originate from the periosteum or periodontal ligament.1,5,6, 9, 10 There is minimal bone lysis associated with PGCG. These lesions, along with pyogenic granuloma and fibrous hyperplasia, are the most common reactive hyperplastic lesions in the oral cavity and have been described in humans, dogs, and cats.1-3,6,11

Central giant cell granuloma (CGCG), on the other hand, is a rare benign, non-metastatic, intraosseous lesion which is further subdivided into non-aggressive and aggressive forms based on its biological behavior. The former is associated with asymptomatic swelling and the latter associated with pain, cortical bone destruction, tooth root resorption, displacement of teeth, and a high recurrence rate.7 Histologically, peripheral and central giant cell granulomas are characterized by variable numbers of multinucleated giant cells intermixed with a dense population of mononuclear spindle-shaped cells and variable amounts of collagenous matrix; however, CGCG may exhibit more foci of haemorrhage and occasional trabeculae of woven bone compared to PGCG.7 Some investigators consider CGCG to be a variant of giant cell tumor of bone, which arise in the ends of long bones, and prefer the term ‘giant cell lesion’ with no distinction of granuloma.6,11 One report in the literature describes a case of ‘giant cell tumour’ within the caudal mandible of a goat which also involved the temporomandibular joint.4 CGCG in humans shows a female predilection (2:1) and is more common in the mandible than maxilla.1 CGCG can also affect extragnathic bones, mainly in the craniofacial region.10

In this case, given the intraosseous location of the mass, the presence of osteolysis, displacement of the incisor teeth, and the lack of mineralized and osteoid matrix, a diagnosis of aggressive central giant cell granuloma was made.

The pathogenesis of CGCG is poorly understood and there is still dispute over whether this is a neoplastic or reactive lesion.7 Giant cells within giant cell granulomas are thought to arise from osteoclasts and positive histochemical staining for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), which is an enzyme unique to osteoclasts, and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B (RANK), which regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation, supports an osteoclastic origin for these masses.2,3

Contributing Institution:

Pathobiology & Population Sciences

The Royal Veterinary College

Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms

Hertfordshire, UK

https://www.rvc.ac.uk/

JPC Diagnosis:

Jaw: Giant cell tumor of bone.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of central giant cell granuloma (CGCG), an entity that is well-described in human literature. The World Health Organization defines CGCG in humans as “an intraosseous lesion consisting of cellular fibrous tissue containing multiple foci of hemorrhage, aggregations of multinucleated giant cells, and, occasionally, trabeculae of woven bone.”7 While this is an apt description of the examined sections in this case, it could well describe several other types of bone tumors with a giant cell component, and differentiating among these entities remains challenging.

Given the paucity of reported veterinary cases, much of what is “known” about this tumor in veterinary species is extrapolated from human literature. Even within the human literature, CGCG remains a contentious entity as the pathogenesis is unknown and experts disagree on fundamental issues, such as whether CGCG is neoplastic or reactive, or whether the lesion is a single neoplastic lesion or a mix of neoplastic and reparative processes.7 Many researchers also believe this entity is simply a giant cell tumor of bone in an uncommon location. What is fairly clear, however, is that the term “granuloma” is a misnomer, as the multinucleated giant cells are osteoclastic rather than macrophagic, as would be expected in a true granuloma.

The biologic behavoir of CGCG is difficult to predict. When surgical resection is elected, reported recurrence rates in humans vary between 11 and 49%.7 The most consistent gross lesion present in aggressive CGCG is perforation of cortical bone; however, despite investigating myriad histologic parameters, no studies have identified reliable histologic features that can predict the course of disease.7

As an interesting side note, a key differential for CGCG in human medicine is cherubism, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by bilateral expansion of the mandible and/or the maxilla which appears in the first few years of life.7 The dysplastic fibrous tissue of the mandible and/or maxilla can extend into the orbital floor and is often accompanied by swelling of the submandibular lymph nodes. These changes cause a characteristic upward tilting of the eyes and fullness of the face, resulting in the cherubic expression that gives the condition its name.12 Cherubism is yet another non-neplastic fibrotic lesion confined to the jaws that cannot be distinguished from other giant cell lesions of bone by histology alone.12

This week’s conference was moderated by Dr. Linden Craig, Professor of Anatomic Pathology at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine. Conference discussion began with a discussion of the bony features present in the examined section, followed by a discussion of basic definitional terms. Mature bone is divided into compact (also called cortical) and cancellous (also called spongy) varieties. The collagen in compact bone is typically oriented into a strong parallel, lamellar arrangement that is organized into osteons, and this dense, compact bone is typically present on the peripheral or exterior portion of the bone. The collagen in cancellous bone is less dense than compact bone, with collagen organized into trabeculae which create cavities that may contain bone marrow. Bone can also be categorized as lamellar or woven, with the former being characterized by mature, organized collagen and the later characterized by more immature, haphazardly arranged collagen fibers. Woven bone represent early osteogenesis and will typically be remodeled and replaced by lamellar bone as it matures. Woven bone can be easily distinguished from lamellar bone by the use of polarized light, which highlights the degree of collagen organization present in the tissue.

Dr. Craig discussed other entities characterized by giant cells, including giant cell tumor of soft parts, giant cell osteosarcoma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, and ethmoid hematomas. Participants discussed the differences between these entities and how the line between reactive and neoplastic seems particularly porous with these entities. Participants noted that “central giant cell granuloma” appears to be a human entity that is rarely diagnosed in veterinary medicine. Though typically occurring in the long bones and digits, participants favored a diagnosis of giant cell tumor of bone, a well-described veterinary entity with a histologic appearance identical to the examined tissue.

References:

- Chandna P, Srivastava N, Bansal V, Wadhwan V, Dubey P. Peripheral and central giant cell lesions in children: institutional experience at Subharti Dental College and Hospital. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(4):440.

- De Bruijn ND, Kirpensteijn J, Neyens IJS, Van den Brand JMA, Van den Ingh TSGAM. A clinicopathological study of 52 feline epulides. Vet Pathol. 2007; 44(2):161-169.

- Desoutter AV, Goldschmidt MH, Sánchez MD. Clinical and histologic features of 26 canine peripheral giant cell granulomas (formerly giant cell epulis). Vet Pathol. 2012;49(6):1018-1023.

- Dixon J, Weller R, Jeckel S, Pool R, Mcsloy A. Imaging diagnosis—the computed tomographic appearance of a giant cell tumor affecting the mandible in a pygmy goat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2016; 57(5):1-3.

- Gandara-Rey JM, Pacheco JMC, Gandara-Vila P, et al. Peripheral giant-cell granuloma. Review of 13 cases. Med Oral. 2002;7(4):254-259.

- Hiscox LA, Dumais Y. Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma in a Dog. J Vet Dent. 2015;32(2):103-110.

- Kruse-Lösler B, Diallo R, Gaertner C, Mischke KL, Joos U, Kleinheinz J. Central giant cell granuloma of the jaws: a clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic study of 26 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):346-354.

- Jané-Salas E, Albuquerque R, Font-Muñoz A, González-Navarro B, Estrugo Devesa A, López-López J. Pyogenic granuloma/peripheral giant-cell granuloma associated with implants. Int J Dent. 2015; 2015:839032.

- Lester SR, Cordell KG, Rosebush MS, Palaiologou AA, Maney P. Peripheral giant cell granulomas: a series of 279 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(4):475-482.

- Motamedi MHK, Eshghyar N, Jafari SM, et al. Peripheral and central giant cell granulomas of the jaws: a demographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2007;103(6);e39-e43.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier; 2016:20-22.

- Papdaki ME, Lietman SA, Levine MA, Olsen BR, Kaban LB, Reichenberger EJ. Cherubism: best clinical practice. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;24(Suppl 1):S6.