Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

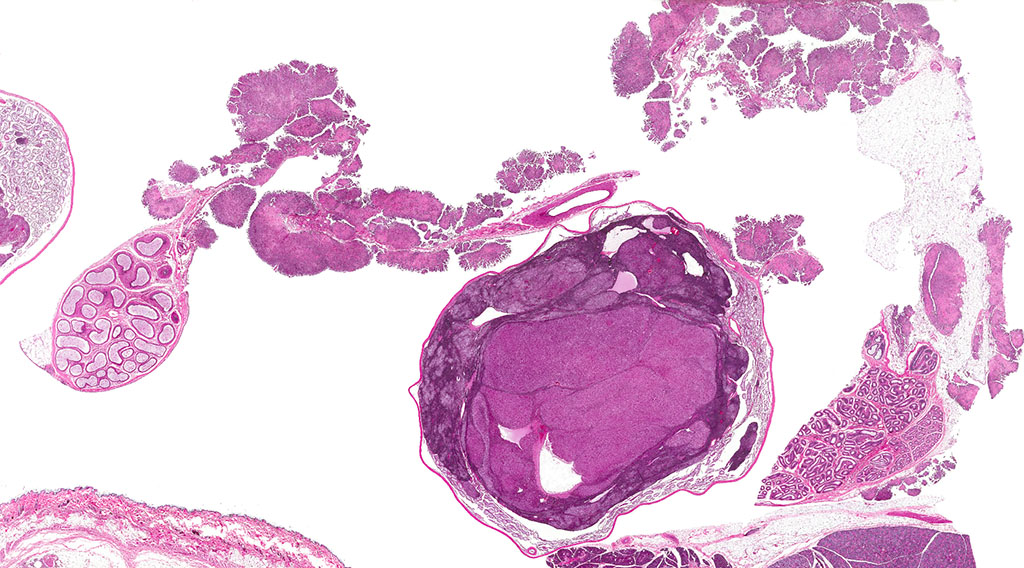

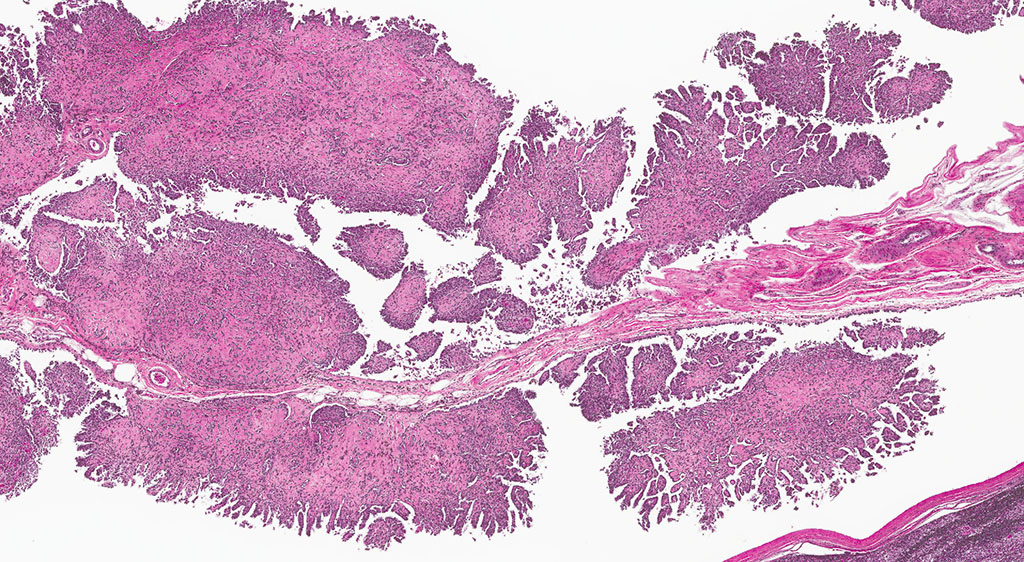

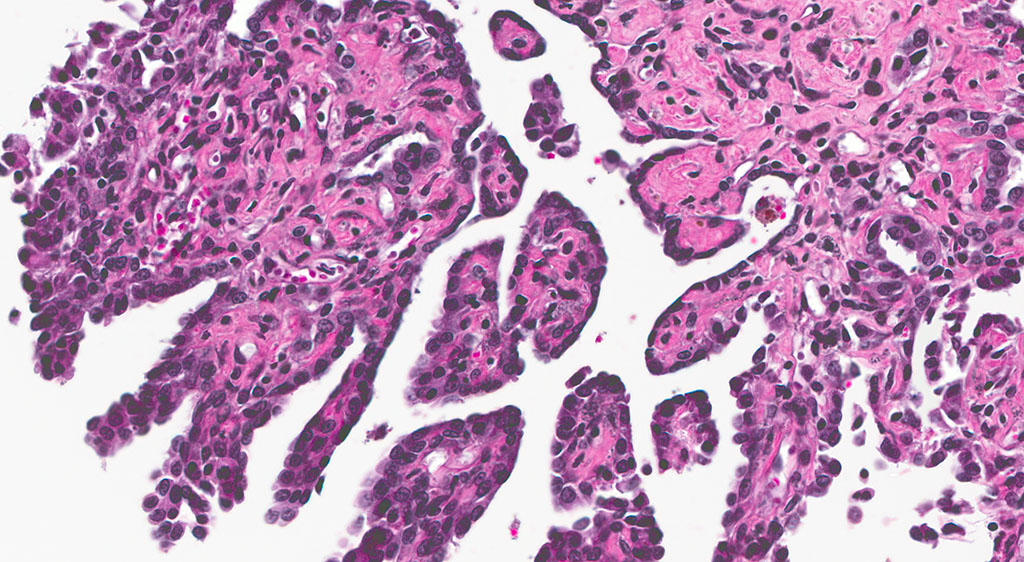

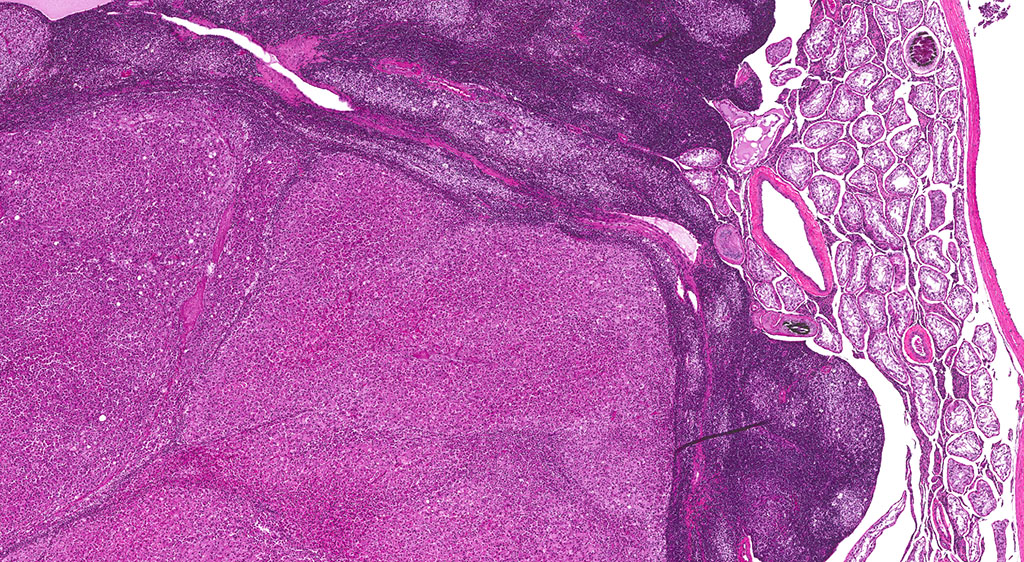

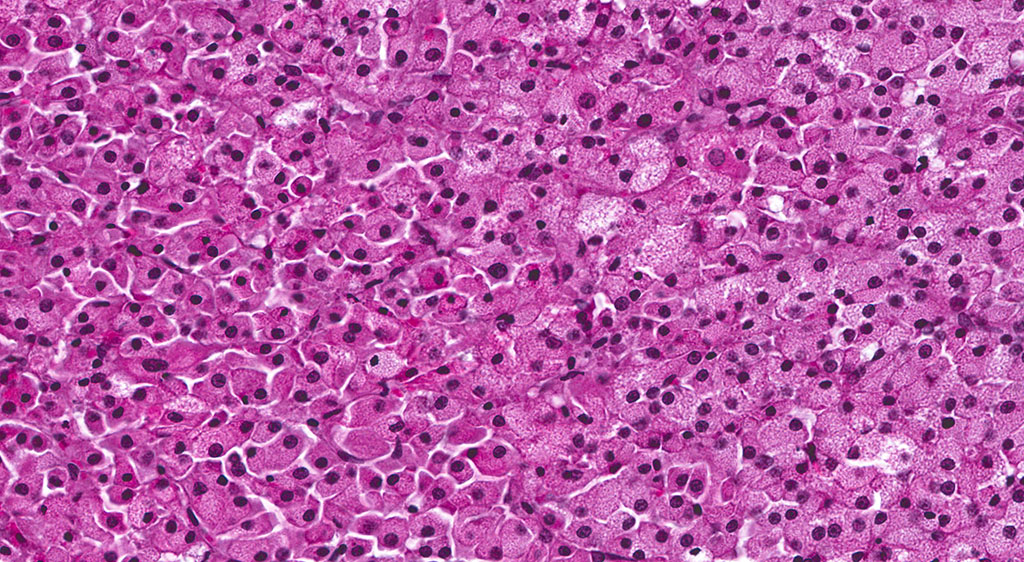

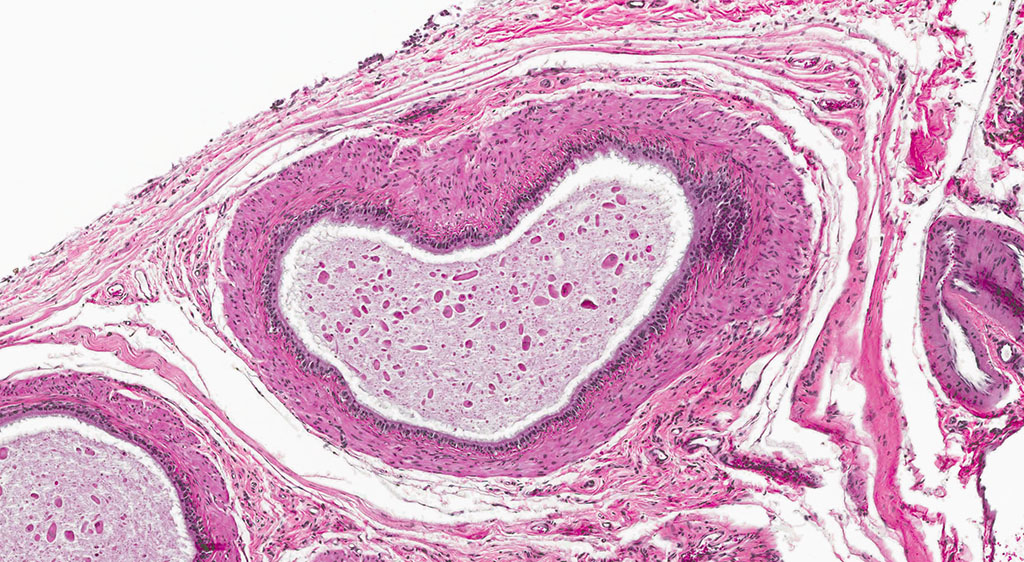

A second approximately 15 x 10mm, discrete, unencapsulated and expansile, multinodular neoplasm is diffusely effacing and replacing the testicular architecture. The neoplasm is composed of polygonal cells arranged in nests and cords supported by small amounts of fine, fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells have variably distinct cell borders with abundant, finely granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and a single, round to oval, eccentric to centrally located nucleus containing 1-2 distinct nucleoli and stippled chromatin. Mitotic figures are rare. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild. Large numbers of lymphocytes are surrounding and infiltrating the neoplasm. The majority of seminiferous tubules are lost; those remaining are shrunken and lined by vacuolated epithelial cells with pyknotic nuclei (tubular degeneration). There are multifocal areas of hemorrhage and mineralization throughout the testis. The contralateral testis is similar in appearance with two, discrete, neoplasms ranging from 2 x 2mm to 3 x 5mm and marked degeneration and atrophy of the seminiferous tubules.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

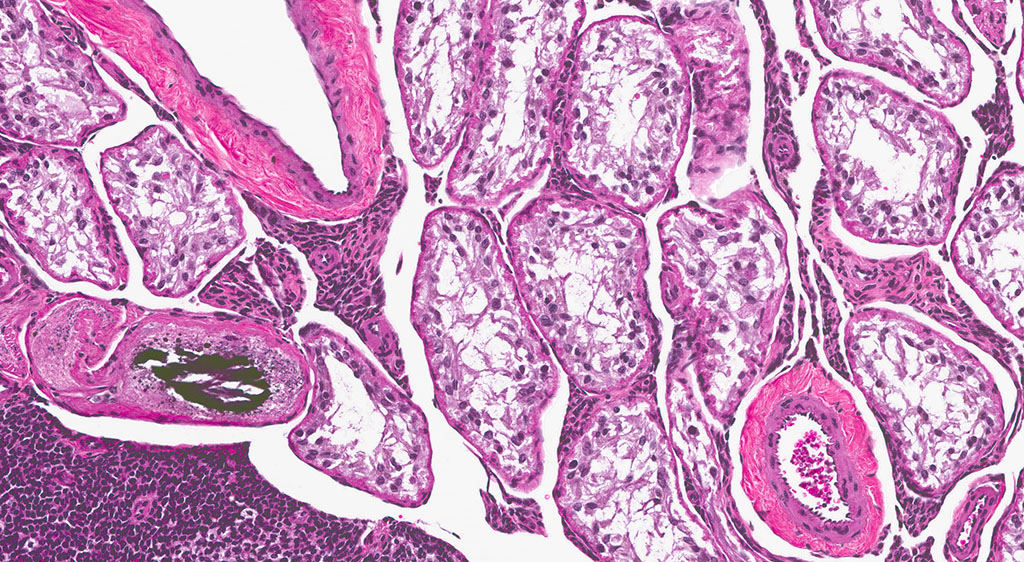

2. Epididymis: 1) Malignant mesothelioma 2) Diffuse, subacute, severe hypospermia and degeneration with germ cell exfoliation and mineralization.

3. Testis, bilateral: 1) Interstitial cell adenoma, multiple 2) Diffuse, chronic, severe, tubular degeneration and atrophy with unilateral, marked lymphocytic infiltrate and multifocal mineralization.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In the male rat, mesotheliomas of the testis, epididymis, and peritoneum are considered to have originated in the tunica vaginalis; all tunica vaginalis mesotheliomas (TVM) are deemed malignant, even those confined to the scrotal sac and lacking features of malignancy, such as local invasiveness, cytological atypia and pleomorphism. Proposed mechanisms of actions for both spontaneous and xenobiotic-induced mesotheliomas include endocrine disruption (leuteinizing hormone, prolactin and testosterone), mechanical stress (compression due to testicular tumors) or oxidative stress (asbestos-induced TVM).4,6,7

In the F344 rat, the most common proliferative disorders of the testes include interstitial cell (Leydig cell) hyperplasia and interstitial cell adenoma. Because interstitial cell adenoma is considered a continuum of interstitial cell hyperplasia, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish hyperplasia from adenoma based solely on differences in cellular morphology.4,7 According to the International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria for Lesions in Rats and Mice (INHAND), Leydig cell hyperplasia typically does not cause compression of the adjacent seminiferous tubules. However, in instances where there is no appreciable compression, proliferative lesions greater than 3 seminiferous tubules in diameter are generally regarded as adenoma.3,4 Interstitial cell adenomas are common spontaneous and xenobiotic-induced neoplasms of rats and mice, particularly the F344 rat with an underlying pathogenesis that reflects endocrine disruption; a hormonal imbalance between the testicular levels of luteinizing hormone receptor and serum testosterone.

Five mechanisms by which hormone imbalance may contribute to Leydig cell tumor formation have been described and include: estrogen agonists (especially in mice), androgen receptor antagonists, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and dopamine receptors, and 5α-reductase inhibitors. Leydig (interstitial) cell adenomas are usually benign, un-encapsulated, discrete neoplasms composed of sheets of uniform polyhedral cells with abundant, finely granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and a single, centrally located nucleus; compression atrophy of the adjacent seminiferous tubules is common. Leydig cell adenomas are an age-related change, observed most frequently in F344 rats in their 2nd year of life, and appear to be inversely correlated with body weight, where increased body weights are associated with higher prolactin levels that reduce Leydig cell tumor incidence.4,7

JPC Diagnosis:

2. Testis, tunica vaginalis: Mesothelioma.

Conference Comment:

Leydig interstitial cells are normally found adjacent to the resident seminiferous tubules in the testis and produce testosterone under the stimulation of luteinizing hormone (LH). Hormonal imbalances as a result of disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis can result in constitutive LH secretion, which is thought to be the main predisposing feature of ICT formation.1 ICTs are composed to two cell types readily recognized by conference participants: polygonal cells with granular vacuolated cytoplasm present within the central part of the neoplasm, in this case, and smaller cells with dense hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm at the periphery.8 The conference moderator cautioned participants to not confuse the latter of these two cell types with lymphocytes. Ultrastructurally, interstitial cells contain lipid droplets, abundant smooth endoplasmic reticulum, and numerous mitochondria with tubulovesicular cristae, and desmosomes.3,8 This neoplasm typically exhibits benign biologic behavior; however, it may be hormonally active and has been associated with hypercalcemia and elevated plasma inhibin levels.1,3,8 It has a characteristic gross appearance of well-circumscribed yellow hemorrhagic nodules on the testes. Larger masses have areas of mineralization and necrosis.8

Mesotheliomas are the third most common spontaneous testicular tumor of rats and are also particularly common in the F344 strain and they commonly occur concurrently with ICT, as in this case.8 Mesothelial cells form a lining around the heart, pleural and peritoneal cavities, and the surface of most organs. In males, it extends into the scrotum and tunica vaginalis and wraps the testes and epididymis.1,2,3,5,8 In male rats, the tunica vaginalis is the most common primary location, with subsequent spread to the rest of the mesothelial-lined surfaces.8 Interestingly, mesothelalial cells have both an epithelial and mesenchymal component. Stains run by the Joint Pathology Center prior to the conference confirmed immuno-reactivity of neoplastic mesothelial cells to both pancytokeratin and vimentin. Other neoplasms of interest that typically express both vimentin and cytokeratin include: chordoma, synovial sarcoma, meningioma, renal cell carcinoma, adrenal carcinoma, and endometrial sarcoma.9 Grossly, mesotheliomas are multiple, well-circumscribed, firm sessile or pedunculated nodules, villous projections, or plaque-like with fibrous adhesions. Concurrent ascites and severe scrotal edema are not uncommon sequelae.8 Ultrastructurally, mesothelial cells have a microvillous cell membrane, junctional complexes between cells, pinocytotic vesicles, and a distinct basal lamina.3,5

As mentioned by the contributor, several studies have attempted to establish a connection between the high incidences of concurrent ICT with mesothelioma in Fisher 344 rats. Some hypotheses include ICT causing direct mechanical stress on mesothelial cells of the tunica vaginalis leading to neoplastic transformation.1,2 Another theory posits that LH and testosterone secretion by neoplastic ICT cells triggers local mesothelium proliferation. Others suggest that Fisher 344 strain-related sensitivity to chemical exposure causes the development of mesotheliomas and ICTs are an unrelated coincidental background lesion.1,2 A definitive connection has not yet been established.

References: