Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 9

November 1st, 2017

CASE III: MS 15-2723 (JPC 4103775).

Signalment: 2-month-old, female, Swiss Webster, Mus musculus, mouse.

History: Mouse observed to have severe head tilt to the right and rolling in bedding.

Gross Pathology: A small-sized, white firm single mass was observed within the wall of the horn of the uterus. No other gross lesions were noted at the time of necropsy.

Laboratory results: None submitted.

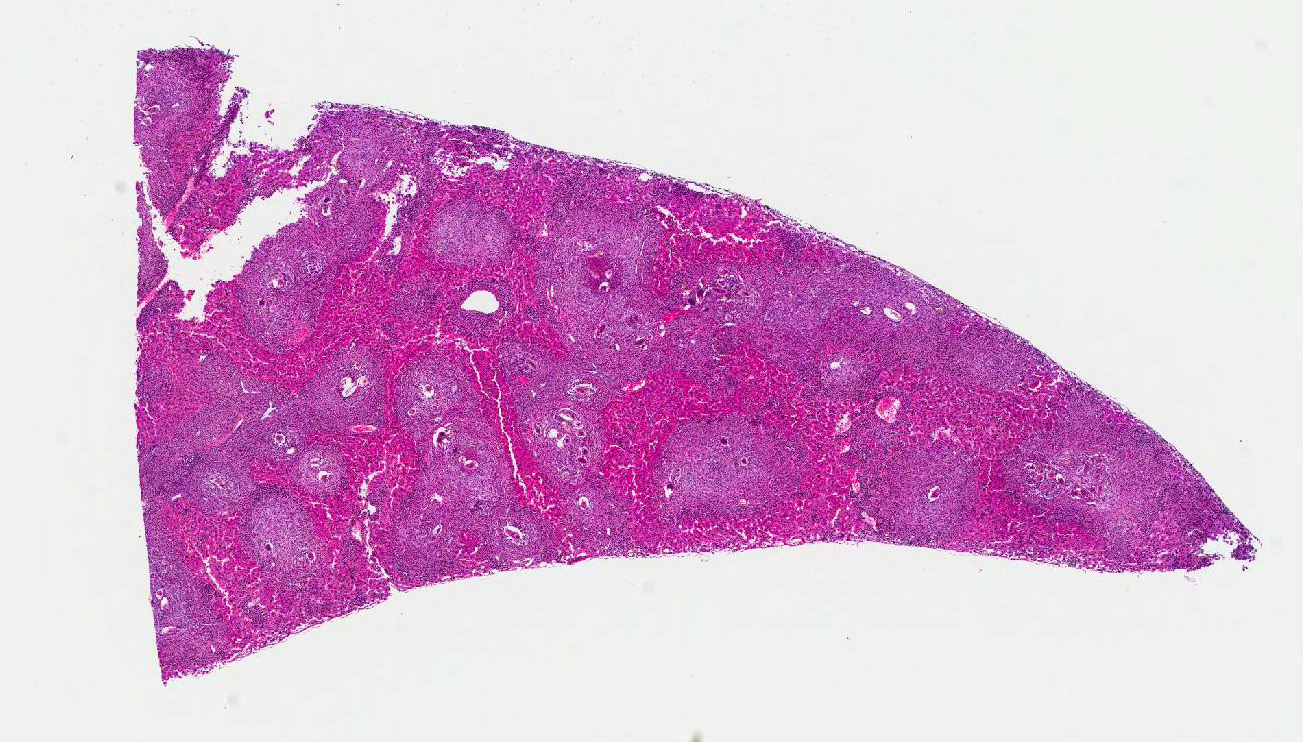

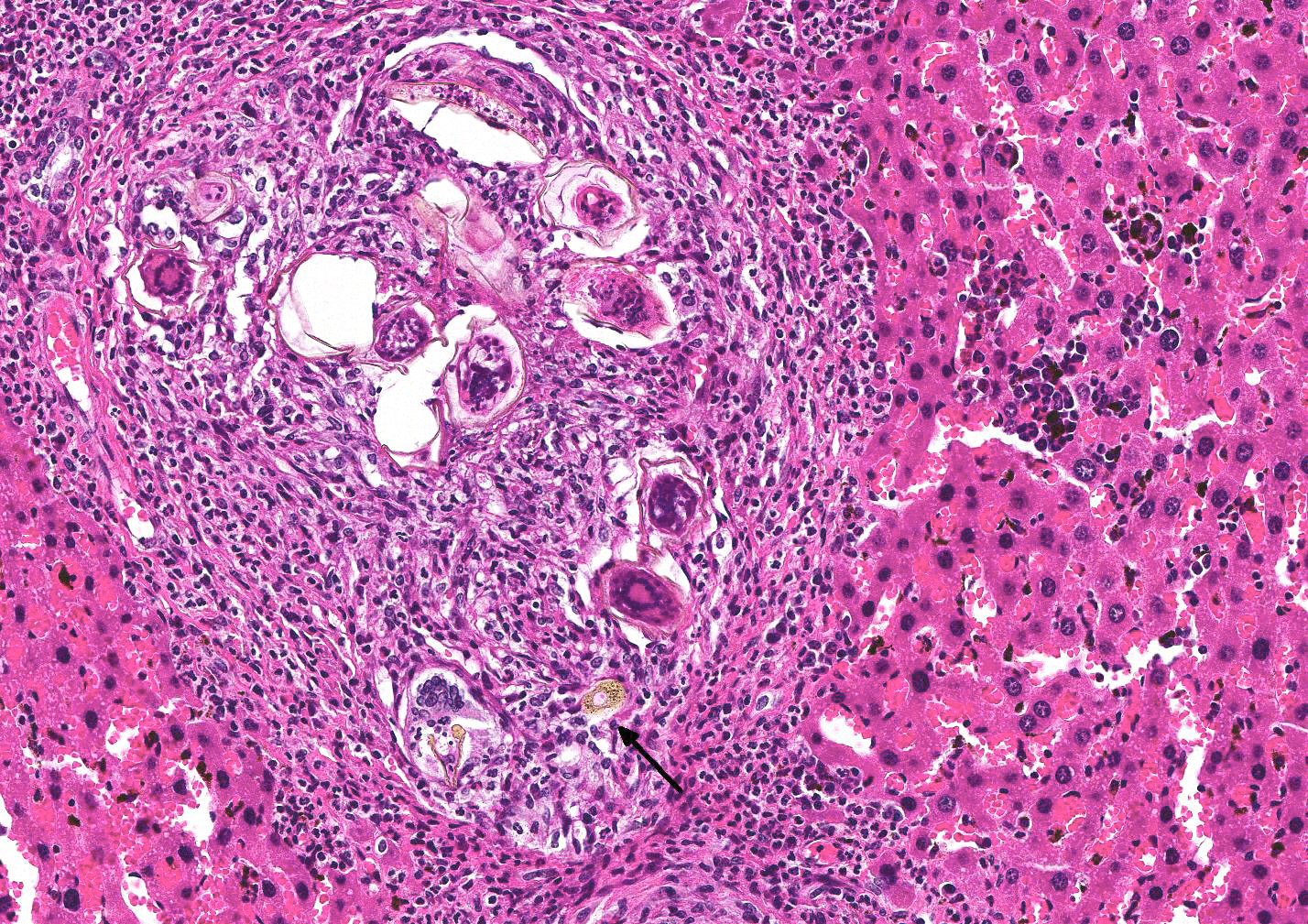

Microscopic Description: Liver (multiple sections submitted) Multifocal to coalescing, peri-portal to portal accumulations of one to multiple larvated parasitic eggs (live, dead, fragmented, egg casing only) surrounded by numerous layers of macrophages, and an outer layer of fibrosis with moderate numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils, and occasional plasma cells and lymphocytes are observed. A rare egg is observed attached to the endothelial lining of a portal vein along with an attached granuloma. Numerous black pigment-laden Kupffer cells (hemozoin) and multiple small accumulations of extramedullary hematopoiesis are observed.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Liver, hepatitis, periportal and portal, granulomatous to pyogranulomatous and eosinophilic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, chronic with multiple parasitic eggs consistent with Schistosomes.

Contributors Comment:

Schistosomiasis affects more than 230 million people worldwide2. S japonicum infects a wide range of mammalian host including dogs, pigs and cattle. S. mansoni can infect rodents and non-human primates2. Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia/bilharziasis, is a disease caused by the trematode Schistosoma, with S. mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium being the most prevalent. Schistosomes, usually referred to as blood flukes, are part of the phylum Platyhelminthes (flatworms), Class Trematoda, and family Schistosomatidae. Schistosoma, or split body, refers to the appearance of the adult males lateral edges that fold to form a groove (gynecophoral canal) where the female worm resides. Schistosomes differ from other trematodes in that there are distinct male and female adult worms. S. haematobium affects the urogenital tract, while the other two are hepatobiliary and intestinal parasites.3

A cercaria is a free-living, actively swimming stage, with a body and a tail. The body contains the acetabulum (ventral sucker); the tail serves to propel, and act as a fulcrum when trying to enter into the skin of a definitive host. Fatty acids (i.e; linoleic acid) and amino acids (i.e; arginine) are chemoattractants to the cercariae.

The cercariae will search for surface skin irregularities associated with hairs, ridges or wrinkles. Once attached to the host, they secrete proteolytic penetrating enzymes by the acetabulum glands; upon entering the skin, the tail detaches and they become known as schistosomules (schistosomulum). At this point, the parasite has changed morphologically and resides in the skin from one to several days before entering the dermal vasculature, after which they begin to feed and mature into the the adult worm stage. Sexes can then be distinguished. Interestingly, the male can develop fully without the female, but the female does not reach sexual maturity in the absence of the male. The female must lie within the males gynecophoral canal for physical and reproductive development. It is believed the adult worms copulate in the liver before migrating to the mesenteric vein.

The male will then anchor the pair to the mesenteric venules by its powerful suckers and muscular body. Females can produce up to 300 embryonated eggs/day, each containing a miracidium. Eggs are released vessel walls, penetrating via egg-released enzymes, and/or by the host own immune response (granuloma formation), resulting in intestinal tract entry. Many eggs do not enter the vasculature and end up in tissues eliciting an inflammatory response; if they enter the intestine, they are shed in the feces.

In fresh water, the egg shell ruptures, releasing motile, multiciliated miracidia, which have approximately 12 hours to find a snail host. Once inside the snail, they lose their cilia and transform into a primary sporocyst a sac-like, asexual breeding chamber with numerous secondary sporocysts. . After approximately 2 weeks, the secondary sporocysts escape the primary sporocyst, and migrate to the snails hepatopancreas and gonads. After another 2 weeks, secondary sporocysts give rise to thousands of cercariae. Once fully developed, the cercariae emerge from the secondary sporocysts, migrate to the anterior of the snail, and are released into the surrounding water to repeat the life cycle. 4.

Schistosomiasis is the condition in which parasitic eggs lodge in the tissues of the definitive host and elicit an chronic inflammatory response. In humans, eggs can also lodge in the intestinal mucosa and/or submucosa leading to the formation of granulomatous pseudopapillomas or pseudopolyps which can cause luminal obstruction, ulceration and/or hemorrhage. 2,3,5,7. Eggs trapped in pre-sinusoidal portal venules secrete soluble egg antigens which are taken up by antigen presenting cells.

Antigen presentation stimulates Th1 cells to secrete IL-2, IFN-gamma and TNF which in turn ilicit a cell mediated response. As the granuloma becomes more organized, Th1 cells are replaced by Th2 cells which produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13, and the synthesis of IgE, completing granuloma maturation. As the lesions persist, fibroblasts are stimulated by egg products and T-cell cytokines, and produce collagen. Over time, there is downregulation of the Th2 response, resulting in the reduction in the size of newly-formed granulomas. This immunomodulation may be driven by cytokines IL-10 and TGF-beta, induce T-regulatory cells and regulate Th1/Th2 responses. T-regulatory cells and B cells are known sources of IL-10, a key regulator of the egg induced granulofibrotic response.

Marked eosinophilia is a common feature of acute schistosomiasis and may occur before egg deposition. The migration of eosinophils from the circulation to site of infection is primarily induced by CCL11. Under the influence of the Th2 response, the combined effect of IL-5 and GM-CSF contribute to increase in eosinophilia.

Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are one of the main sources of collagen in the liver and play a crucial role in schistosome-induced fibrogenesis. When activated by IL-13, they differentiate into myofibroblasts, producing collagen. Chemokines associated with HSC recruitment include CXCL1, CCL7, CCL12, and CCL21. Schistosome eggs can inhibit the differentiation of HSC into myofibroblasts; S. mansoni has the ability to reverse HSC differentiation to their quiescent state1.

Chronic schistosomiasis leads to extensive periportal fibrosis, a condition known as Symmers pipestem fibrosis. Portal fibrosis leads to portal hypertension which contributes to splenomegaly, and esophageal and gastric varices5,7. Exsanguination by esophageal variceal bleeds is the major cause of death in humans7.

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, granulomatous and eosinophilic, random to portal, with numerous schistosome eggs and moderate intrahistiocytic fluke excrement, Swiss Webster (Mus musculus), mouse.

Conference Comment: Schistosomiasis, a fluke infection utilizing snails as intermediate hosts, is prevalent in domestic animals in Asia, Africa, and tropical areas; interestingly this condition does not often cause clinical disease. Generally, damage caused by flukes is due to the orientation of adults and eggs within the vasculature of the liver; lungs, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and nasal cavity. The schistosomes life cycle is similar to other flukes and outlined nicely by the contributor.

Heterobilharzia americana causes clinical disease in dogs, particularly in the southern United States (Louisiana and Texas). The raccoon serves as the definitive host, while dogs and a multitude of other species (bobcat, armadillo, Brazilian tapir, beaver, coyote, mountain lion, mink, nutria, opossum, red wolf, swamp rabbit, and white-tailed deer) serve as accidental hosts. H. americana causes hepatic granulomatous lesions which may result in a variety of clinical signs including: mucoid to bloody diarrhea, lethargy, weight loss, vomiting, anorexia, and ascites. In some cases, dogs experience hypercalcemia due to release of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol from macrophages resulting from the chronic inflammatory process. Microscopically, liver lesions are characterized by multifocal lymphoplasmacytic, eosinophilic to granulomatous inflammation surrounding mineralized eggs that are often arranged in linear arrays. PCR is required to differentiate H. americana from other schistosomes by identification of specific subunit ribosomal RNA.6

In this case, the species of Schistosoma is unknown. Dr. Chris Gardiner, Consultant for Veterinary Parasitology, Joint Pathology Center, reviewed the case and was also unable to specify which type.

There was spirited discussion during the conference about what to call the brown granular pigment within Kupffer cells. It is a fluke byproduct which may represent blood pigment, fluke excrement, or a combination of both.

Veterinary Pathology

Division of Veterinary Resources

Office of Research Services

National Institutes of Health

https://www.ors.od.nih.gov/sr/dvr/drs/Pages/default.aspx

References:

1. Chuah C, Jones MK, Burke ML, McMannus DP, Gobert GN. Cellular and chemokine-mediated regulation in schistosome-induced hepatic pathology. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(3):141-150.

2. Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014:383:2253-2264.

3. Elbaz T, Esmat G. Hepatic and intestinal schistosomiasis: review. J Adv Res. 2013:4:445-452.

4. Lewis FA, Tucker MS. Schistosomiasis. In: Toledo R, Fried B, eds. Digenetic Trematodes, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014:47-75.

5. Olveda DU, Olveda RM, McManus DP, Cai P, et al. The chronic enteropathogenic disease schistosomiasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2014; 28:193-203.

6. Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017: 91-94.

7. Shaker Y, Samy N, Ashour E. Hepatobiliary schistosomiasis. J Clinic Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:212-216.