Signalment:

11-year-old, castrated male, Labrador retriever, (

Canis familiaris).The patient presented six months prior to euthanasia for

evaluation of a cardiac arrhythmia and a several month history of intermittent

coughing which had become more severe in the two days before initial

presentation. An intermittent split P wave was noted on the ECG. Thoracic radiographs

revealed a markedly enlarged heart, right atrial enlargement, enlarged

pulmonary vessels, and a diffuse broncho-alveolar pattern. Echocardiography

showed a space-occupying mass in the left atrium with mitral and tricuspid

valve regurgitation. The patient was discharged with furosemide and returned six

months later with exercise intolerance and respiratory distress. At that time

due to the patients declining condition the owner elected euthanasia.

Gross Description:

A 5 x 6 x 8 cm, firm, multinodular mass is present on the

proximocaudal aspect of the heart base, resting on the left atrium. On cross

section, the mass is highly vascular and has a mottled red-to-brown mosaic

pattern. The mass surrounds the pulmonary arteries, compressing the left

pulmonary artery, but it is still patent. The mass is proximal to the

pulmonary veins that are not compressed. Tumor invasion into the left atrial

lumen is characterized by numerous nodular small projections, up to 0.5 cm,

covered by intact endocardium. Left atrial luminal size is decreased due to

compression by the mass. Mild endocardiosis of the mitral and tricuspid valves

is evident. The right ventricle is distended and dilated in addition to an

overall enlarged heart.

The

abdomen contains 4 liters of sero-sanguinous clear fluid, with another 2 liters

of clear creamy yellowish fluid in the thoracic cavity. The spleen has multiple

firm white and hemorrhagic masses ranging from 1 mm to 3 cm in size. The

consistencies of the splenic masses are similar to the heart mass. The left

anterior lung is very pale, soft, and slightly decreased in size due to

compression by the left atrial mass. Mediastinal lymph nodes are enlarged with

effacement of normal architecture.

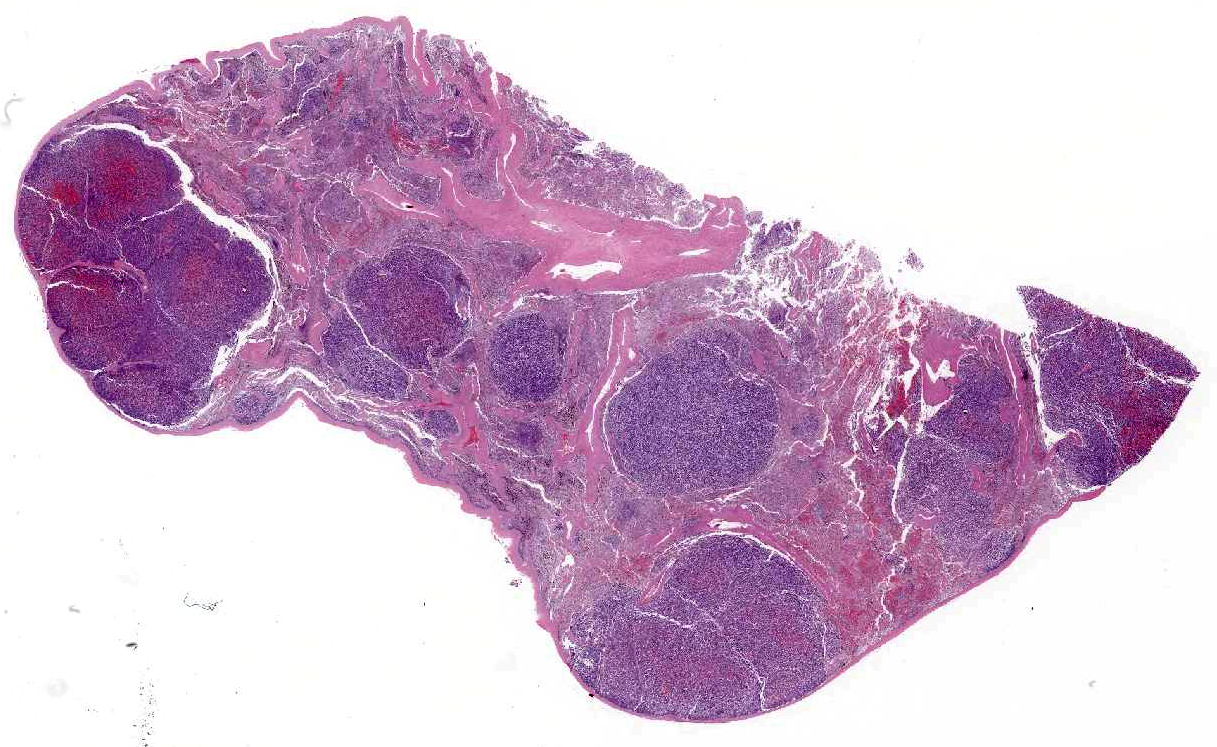

Histopathologic Description:

Spleen:

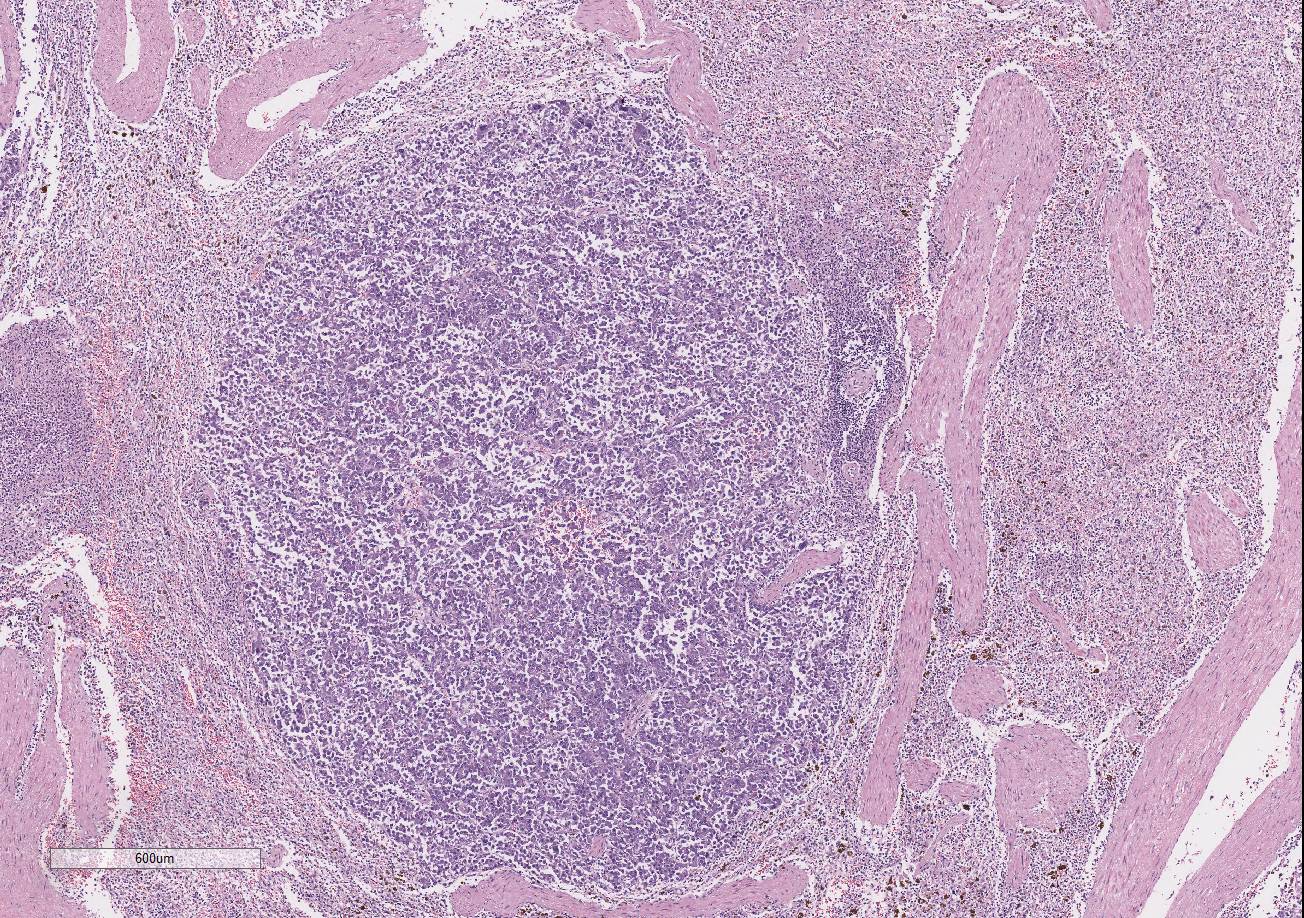

There are multiple variably-sized solid nodules

effacing and replacing the splenic parenchyma. The neoplastic nodules are well

demarcated and expansile. They are composed of large islands of polygonal cells

separated by large connective tissue branches and supported by fine fibro-vascular

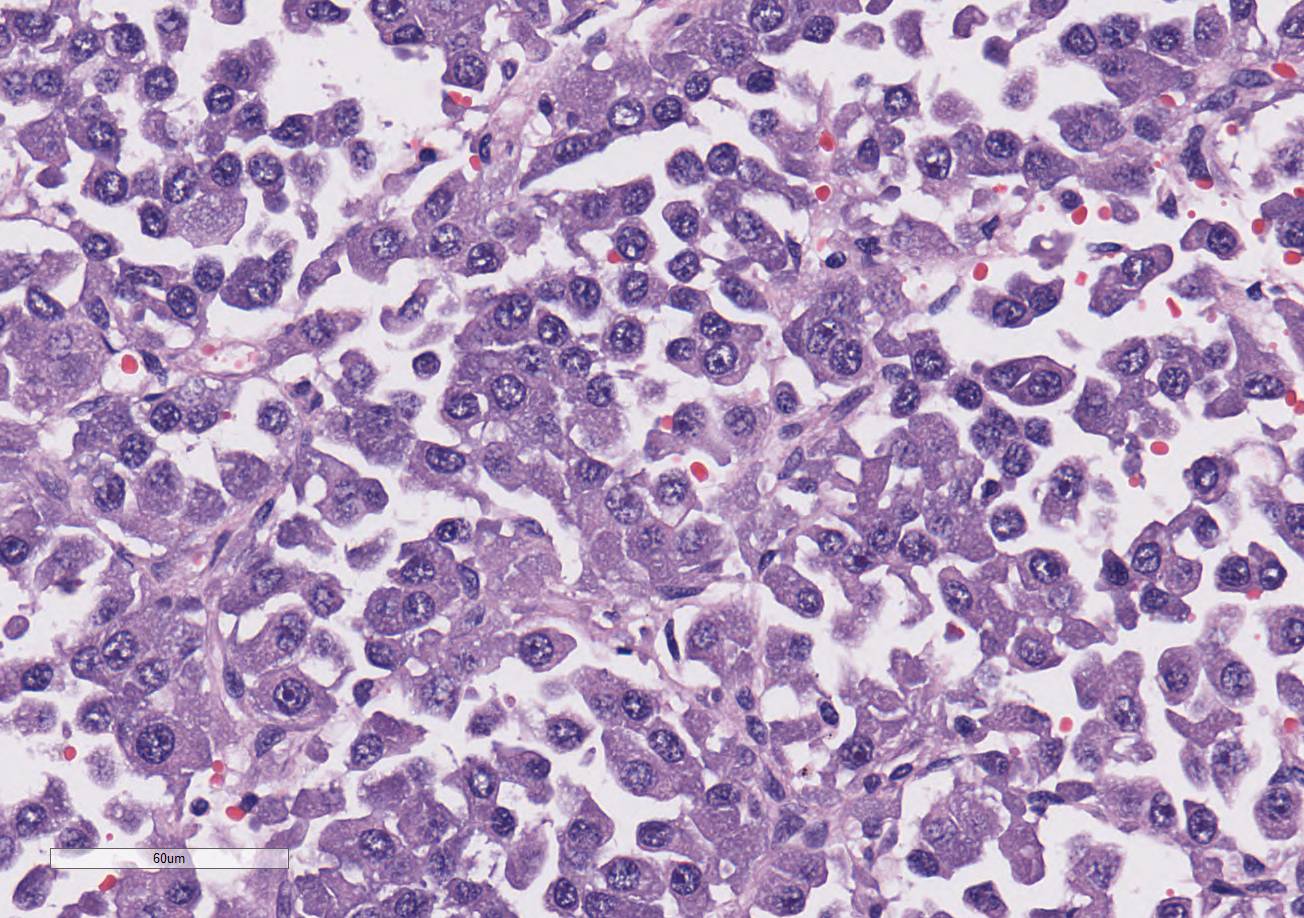

stroma that subdivide the cells in small ribbons. The tumor cells are cuboidal

to polyhedral in shape with a round nucleus and a moderate amount of granular

lightly amphophilic cytoplasm. The cells are aligned along the small

capillaries forming small packets where the cells show polarity with the

cytoplasm towards the vessels. Mitotic activity is 11 mitotic figures in 10

hpf. There are areas of marked aniso-karyosis and occasional megalokaryosis

(polymorphism) with prominent nucleoli. The large cells show a round

eosinophilic prominent nucleolus.

The adjacent splenic parenchyma is compressed and attenuated.

There are small multiple aggregates of macrophages filled with large granulated

golden pigment (hemosiderin- previous hemorrhages). The smooth muscle

trabeculae are closer than expected due to collapse of the parenchyma with very

few follicles.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Heart: Chemodectoma

2. Heart: Mild diffuse mitral and tricuspid valve myxomatous

degeneration

3. Spleen: Chemodectoma, metastasis

4. Liver: Chronic severe congestive hepatopathy

5. Lymph Nodes: Chemodectoma, metastasis

Lab Results:

Upon initial presentation, NOVA results are as follows:

Glucose: 118 mg/dL (60-115)

Ca++: 1.35 mmol/L (2.2-3.0)

Mg++: 0.49 mmol/L (1.5-2.5)

PCO2: 26.1 mmHg (34-40)

PO2: 49.1 mmHg (85-100)

PO2: 49.1 mmHg (85-100)

SO2: 85.4 % (>90)

BEecf: -7.3 mmol/L ([0]-[+6])

nCa: 1.37 mmol/L (1.13-1.33)

nMg: 0.50 mmol/L (0.26-0.41)

Condition:

Neuroendocrine carcinoma

Contributor Comment:

Spleen

is the only tissue submitted. Chemodectomas are primary neuroendocrine tumors

arising most commonly from the chemoreceptor organs of the aortic and carotid

bodies.

1,2,4,12 Other chemoreceptors that rarely develop neoplasia

include the nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve, ciliary ganglion in the orbit,

the pancreas, and the glomus jugulare along the recurrent branch of the

glossopharyngeal nerve.

11 They are synonymous with heart base tumors

or non-chromaffin, extra-adrenal, paragangliomas in veterinary medicine.

3,4

Chemodectomas

are uncommon neoplasms most often described in canines where they have an

incidence of 0.19%.

14 Chemo-dectomas are the second most common

cardiac tumor, behind hemangiosarcomas, representing 8% of cardiac tumors.

14

Contrary to humans, aortic body tumors are the more common form of chemodectoma

in animals with carotid body tumors being less common and more malignant.

4

In dogs, aortic body tumors are encountered up to four times more frequently

than carotid body tumors.

12 The aortic body is located adjacent to

the adventitia of the aortic arch at the bifurcation of the subclavian artery

while the carotid body is located at the bifurcation of the common carotid

artery.

1,4,14 Paren-chymal cells of neuroectodermal origin and

sustentacular or stellate cells are the primary cell types that make up the

chemoreceptor organs.

4,11 The function of the aortic and carotid

bodies is to sense fluctuations in the carbon dioxide, pH, and oxygen tension

in blood, which helps to regulate respiration and circulation.

4,7

The aortic and carotid bodies can increase heart rate and elevate arterial

blood pressure through the sympathetic nervous system and alter the depth, minute

volume, and rate of respiration through the parasympathetic nervous system.

4

The chemoreceptor system is considered part of the parasympathetic nervous

system, as it does not secrete catecholamines; however, the presence of secretory

granules in the cytoplasm of the glomus cells, the functional cells of

chemoreceptors, is inconsistent with this finding.

1,11,12

Due

to the lack of catecholamine production, the tumors clinical manifestations

are the result of being a space-occupying lesion. Smaller adenomas may go

undetected, as they can be too small to cause clinical signs, while larger

adenomas may press on the atria or displace the trachea and partially surround

the major vessels at the base of the heart. Aortic body tumors can also be

locally invasive and invade the lumen of the surrounding great vessels or heart

chambers hindering blood flow.

4 Common clinical manifestation of

aortic body tumors include ascites, pulmonary edema, nutmeg liver, hemothorax,

hemopericardium, anasarca, dyspnea, cyanosis, splenomegaly, and arrhythmias.

6,10,12,15

Many of these clinical manifestations are consistent with right-sided

congestive heart failure brought on by the tumor acting as a space occupying

lesion or by local invasion of vessels resulting in the obstruction of blood

flow.

15 Another way aortic body tumors cause lesions is through

metastasis to other parts of the body. It is rare for an aortic body tumor to

metastasize, with the most common locations being the lungs and liver.

4

However, other locations have been identified including lymph nodes,

myocardium, kidney, adrenal gland, bladder, spleen, and even bone.

4,5,7,12,14

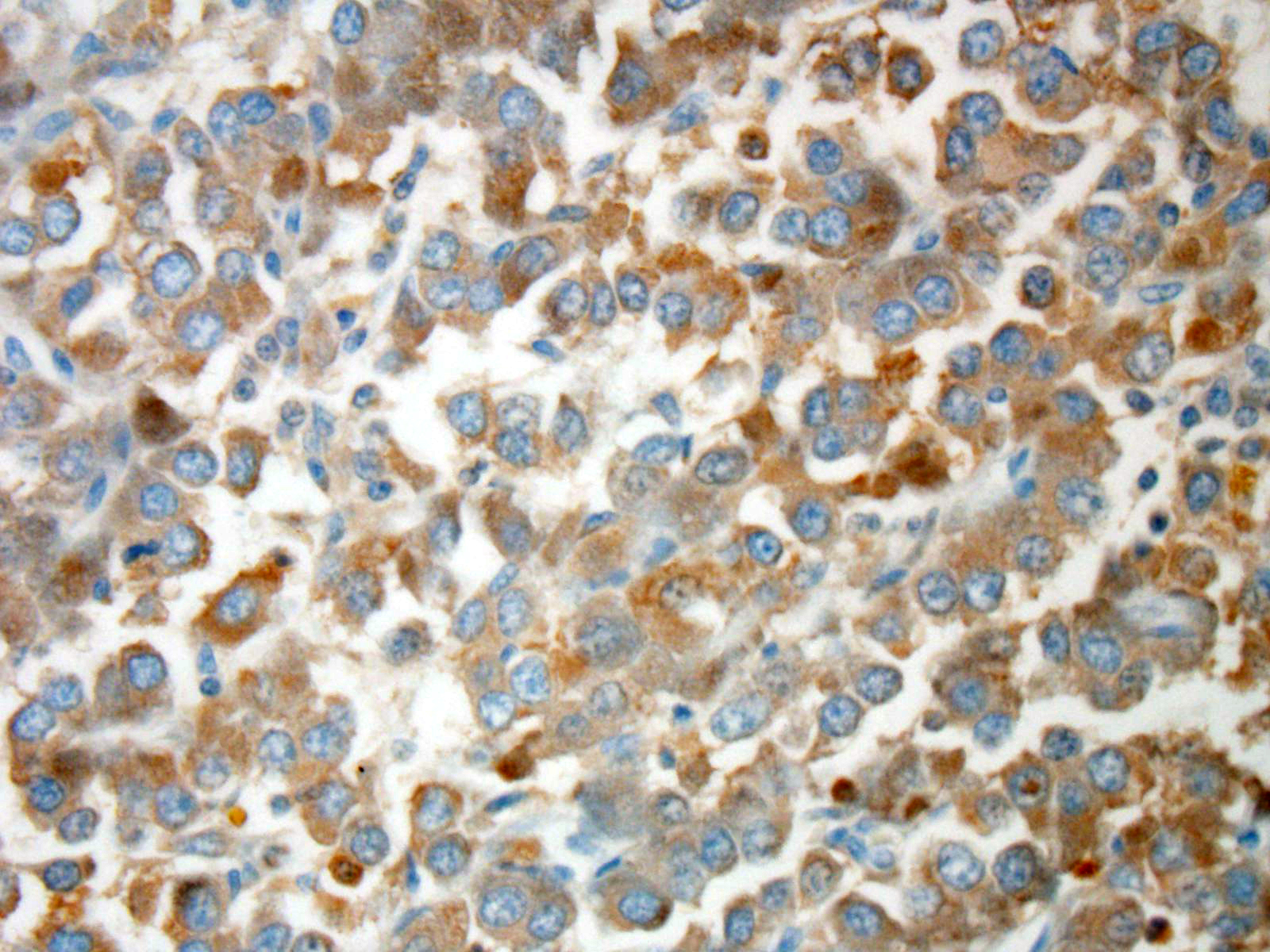

Immuno-histochemistry has been valuable to definitively confirm the diagnosis

of chemodectomas.

8,12,15

JPC Diagnosis:

Spleen: Neuroendocrine carcinoma, metastatic, Labrador retriever,

Canis

familiaris.

Conference Comment:

The

contributor provides an excellent summary of the key features of chemodectomas

in dogs. As is the tradition at the Joint Pathology Center, conference

participants are not provided the full signalment, history, gross necropsy

findings, or results of additional histo-chemical and immunohistochemical

stains prior to the conference. Conference participants described nests and

packets of neoplastic polygonal cells with small, round, hypochromatic nuclei

separated and supported by a delicate fibrovascular stroma, and aptly

determined the neoplasm to be of neuroendocrine origin; however, without the additional

clinicopathologic information, the site of origin could not be definitively determined

from histopathologic evaluation alone. As a result, participants

discussed the most likely sites of origin for neuro-endocrine chemoreceptor

paragangliomas (also known as chemodectomas and glomus tumors) in animals.

Chemoreceptor organs are present in several sites of the body,

such as the cartotid body, aortic body, nodose ganglion of the vagus nerve,

ciliary ganglion of the orbit, pancreas, jugular vein, middle ear, and glomus

jugulare near the glossopharyngeal nerve.

13 As mentioned by the

contributor, they are all highly sensitive to changes in blood pH, oxygen

tension, and temperature, and can rapidly change respiratory and heart rate via

the autonomic nervous system.

13 Metastasis occurs in about 1/3

rd

of cases of chemodectomas arising from the carotid body, and multicentric

neoplastic trans-formation has been frequently reported in brachiocephalic dogs,

possibly because of breed-associated anatomic malformations in the upper

respiratory tract resulting in chronic hypoxia.

13

Neoplastic cells in

neuroendocrine tumors contain variable numbers of cytoplasmic secretory

granules, best visualized by electron microscopy. Additionally, the number of

granules is used to distinguish adenomas, which contain more numerous granules,

from carcinomas. In addition, neoplastic cells typically will be immunopositive

for chromogranin-A, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), synapto-physin, and S100

protein. Prior to the conference, the JPC performed tissue immunohistochemistry

for chromogranin-A, NSE, and synaptophysin. Unfortunately neoplastic cells were

immunonegative for all three stains; however, participants speculated the

results may be due to suboptimal tissue fixation.

13

References:

1. Aupperle H, März I, Ellenberger C, Buschatz S, et al. Primary

and secondary heart tumours in dogs and cats.

J Comp Pathol. 2007; 136:18-26.

2. Brown PJ, Rema A, Gartner F. Immunohistochemical

characteristics of canine aortic and carotid body tumours.

J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med.

2003;50:140-144.

3. Balaguer L, Romano J, Neito JM, Vidal S, Alverez

C. Incidental finding of a chemodectoma in a dog:

Differential diagnosis.

J Vet Diagn Invest. 1990; 2:339-341.

4. Capen CC: Endocrine glands.

In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy,

and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. St. Louis, MO:

Elsevier; 2007:425-428.

5. Eriksson, Malin. "Aortic Body Tumors in Dogs."

(2011). http://stud.epsilon.slu.se/2545/1/Eriksson_m_110502.pdf

6. Ehrhart N, Ehrhart, EJ, Willis J, Sisson D, Constable P, Greenfield

C, Manfra Maretta S,

Hintermeister J. Analysis of factors affecting survival in dogs with aortic

body tumors.

Vet Surg.

2007; 31(1):44-48.

7. Johnson KH. Aortic body tumors in dogs.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1968; 152(2):154.

8. Khodakaram-Tafti A, Shirian S, Shekarforoush SS, Fariman H,

Daneshbod Y. Aortic body chemodectoma in a cow: Clinical, morphopathological,

and immunohistochemical study.

Comp

Clin Pathol. 2011;20(6):677-679.

9. McManus BM, Allard MF, Yanagawa R. Hemodynamic disorders. In:

Rubins Pathology: Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. ed. Rubin

R, Strayer DS. 5

th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters-Kluwer;

2008:231-232.

10. Noszczyk-Nowak, Agnieszka, Nowak M, Paslawska U, Atamaniuk W,

Nicpon J. Cases with manifestation of chemodectoma diagnosed in dogs in

Department of Internal diseases with Horses, Dogs and Cats Clinic, veterinary

medicine faculty, University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Wroclaw,

Poland."

Acta Veterinaria

Scandinavica. 2010; 52:35.

11. Owen TJ, Bruyette DS, Layton CE. Chemodectoma in dogs.

Comp

Cont Educ Pract. 1996;18:253265.

12. Paltrinieri S, Riccaboni P, Rondena M, Giudice C. Pathologic and immunohistochemical findings in a

feline aortic body tumor.

Vet Pathol.

2004; 41:195-198.

13. Rosol TJ, Grone A. Endocrine glands. In: Maxie MG, ed.

Jubb,

Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 3. St.

Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:354-357.

14. Ware WA, Hopper DL. Cardiac tumors in dogs: 19821995.

J

Vet Intern Med

. 1995; 13: 95-103.

15. Willis R, Williams AE, Schwarz T, Paterson C, Wotton PR. Aortic

body chemodectoma causing pulmonary oedema in a cat. J

Small Anim Pract.

2001;

42:20-23.