WSC 2023-2024, Conference 21, Case 3

Signalment:

7-year-old, female spayed Bassett hound (Canis familiaris)

History:

The patient initially presented to a veterinary clinic with a two-day history of inappetence and lethargy. Blood work performed in-house at that time revealed elevated liver enzyme activities. Splenomegaly was detected by ultrasound, and the spleen was consequently removed surgically. Three months later, the dog re-presented with exophthalmos of the left eye. The clinician diagnosed a luxated lens and glaucoma. The eye was enucleated and submitted for histology. The clinical concern was metastasis to the eye from the previously diagnosed splenic mass.

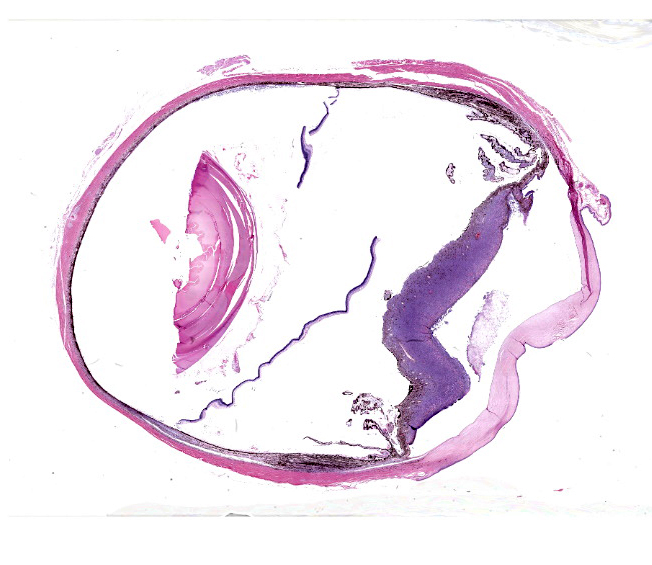

Gross Pathology:

The submitted trimmed globe was 24 x 24 x 27 mm.

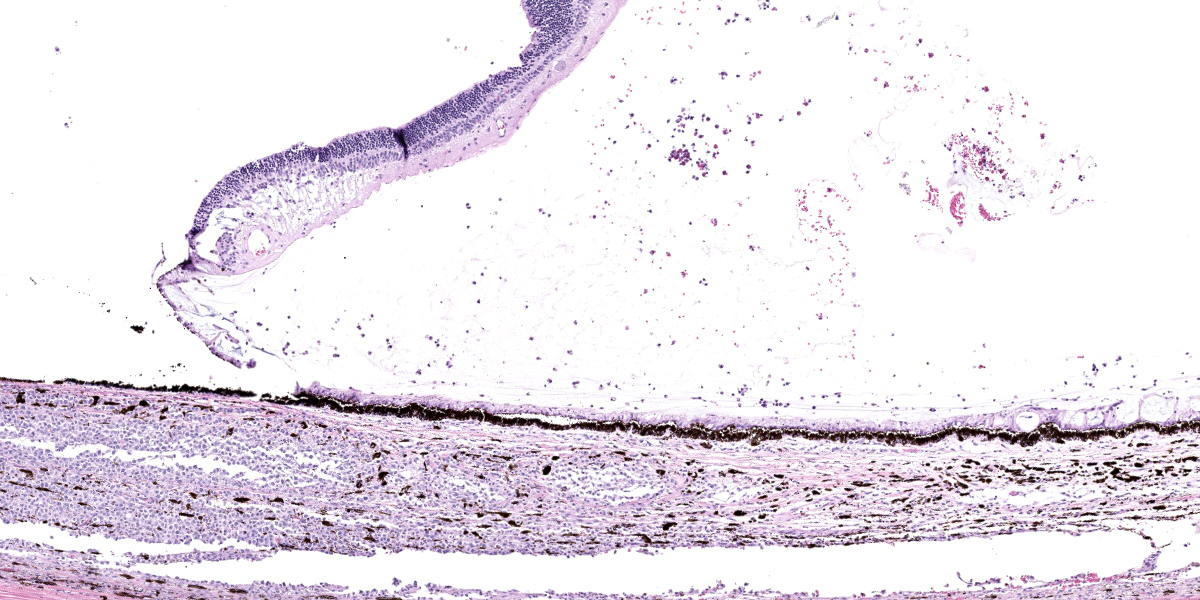

Microscopic Description:

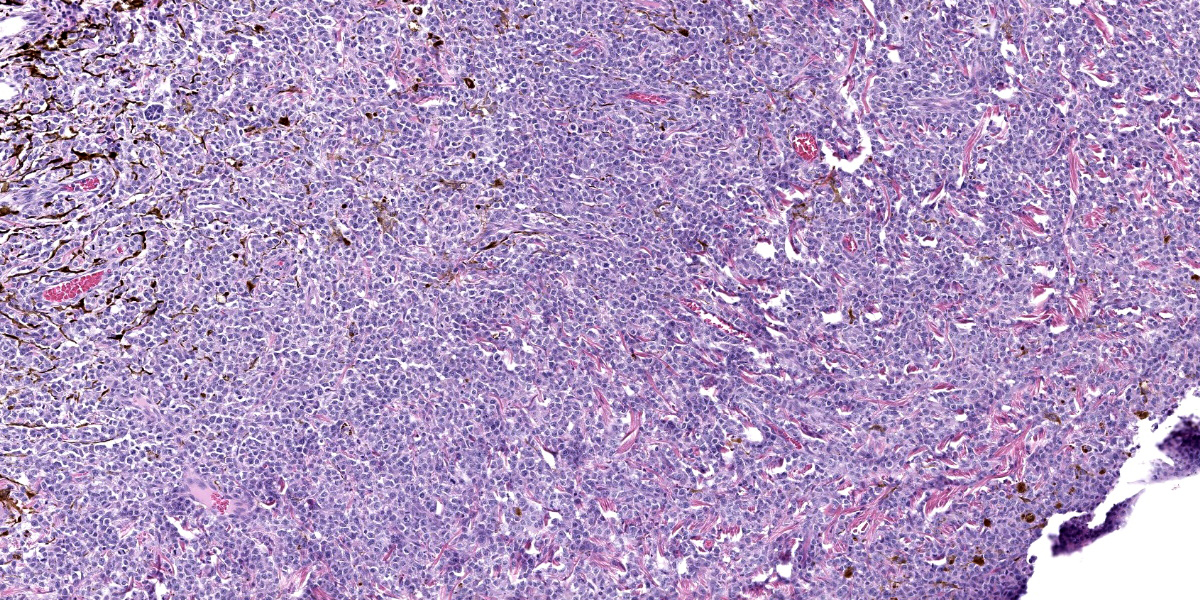

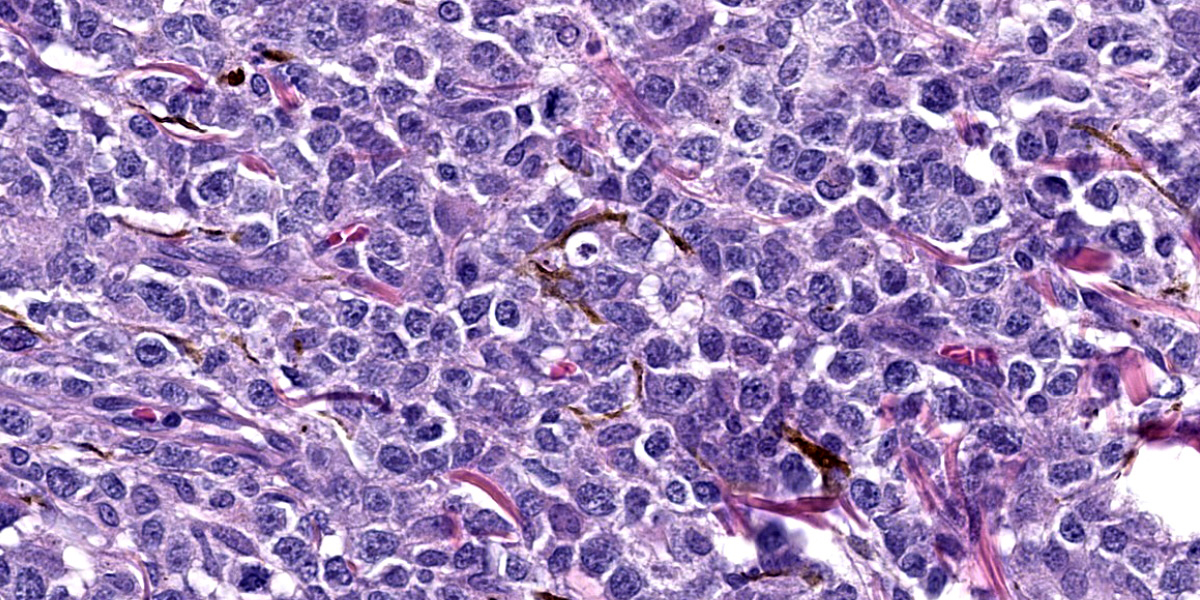

Globe: There is severe multifocal infiltration of the uveal tract by unencapsulated sheets of moderately pleomorphic round cells, resulting in thickening of the choroid (to 600 µm) and iris (to 2.5 mm). Neoplastic cells have scant, lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and irregularly round to elliptical nuclei with 1-2 atypically large nucleoli. The mitotic rate averages 2-4 per HPF. There is moderate anisokaryosis. Similar cells are present in the lumina of choroidal vessels, as well as in ciliary process epithelium and in the anterior chamber. The neoplastic round cells form sheets adherent to the anterior aspect of the iris. They are also present between the sensory and non-sensory retina, admixed with melanin-containing macrophages of presumptive retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) origin. Modest numbers of small lymphocytes, interpreted as an inflammatory response, are present at the margins of the intra-uveal neoplastic infiltrates. Other changes include retinal detachment with tombstone hypertrophy of the RPE, deep neovascularization of the corneal substantia propria, hemorrhage with fibrin exudation in the anterior chamber, and hemorrhage in the posterior chamber and in the vitreous. There is posterior luxation of the lens, edema of ciliary processes, mild vacuolation of lens fibers at the lenticular bow, cytoplasmic vacuolation with partial loss of corneal endothelium, and partial occlusion of the drainage angle.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Eye, uvea: Lymphoma, metastatic, with secondary retinal detachment, intraocular hemorrhage, uveitis and glaucoma, Basset hound, canine.

Contributor’s Comment:

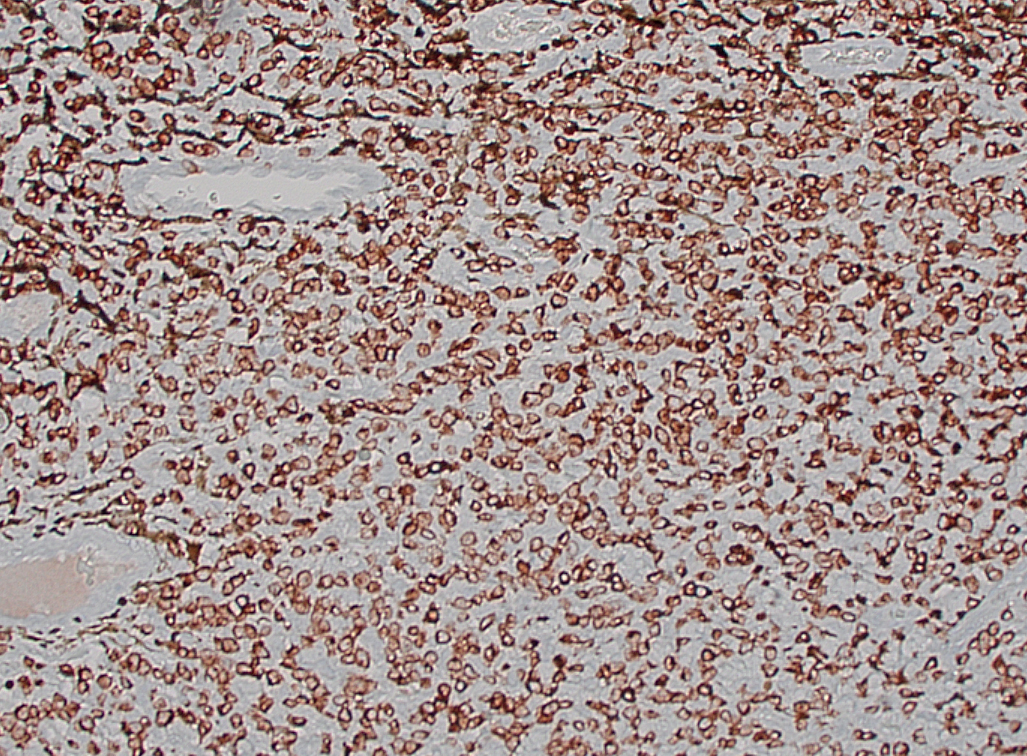

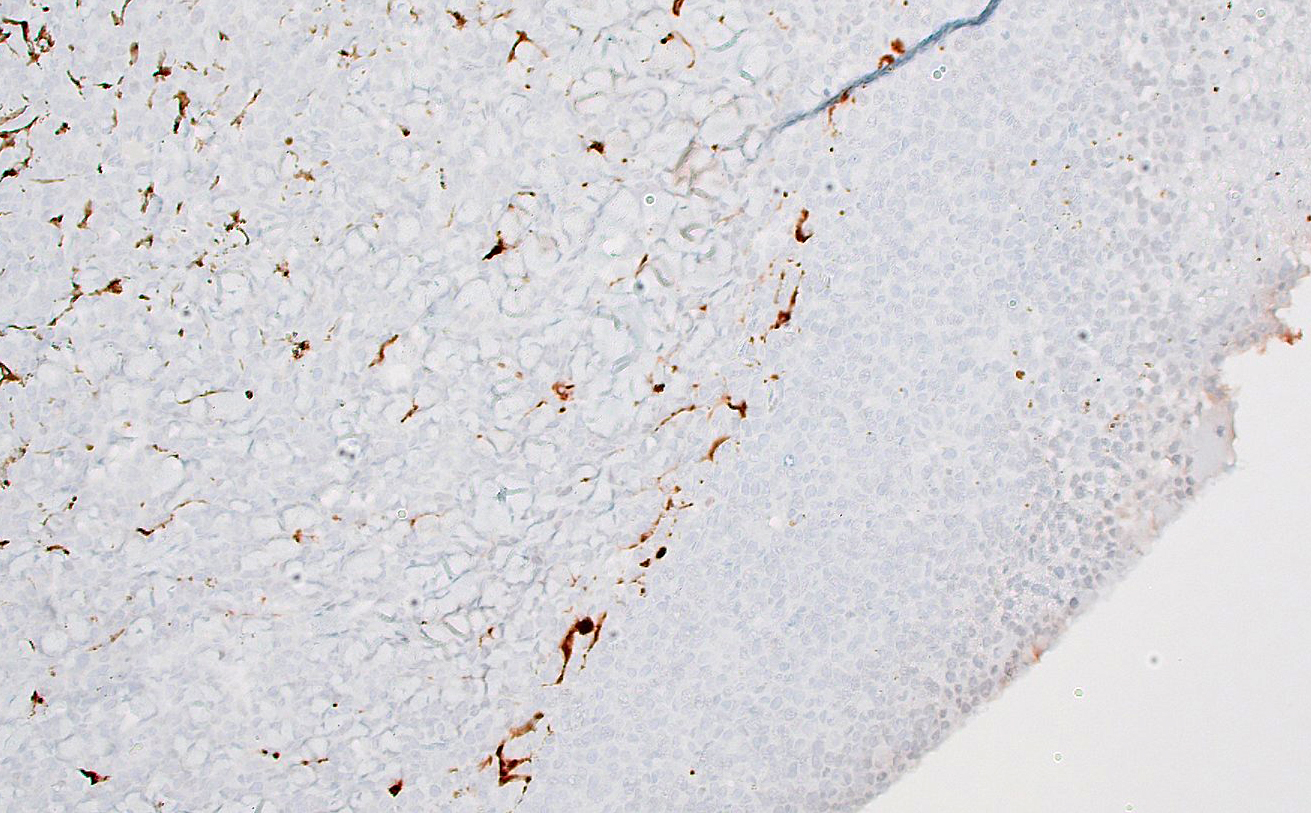

The dog was diagnosed three months earlier with intrasplenic T cell lymphoma. This was based on positive staining for CD3 and negative staining for CD79a. A comparable staining pattern was evident in the intraocular mass. The clinician’s concern about intraocular metastasis, resulting in lens luxation and glaucoma, was warranted.

Lymphoma is the most common metastatic intraocular tumor of dogs.1 It may occur in as many as one third of canine lymphosarcoma cases.8,11 Primary intraocular lymphomas (presumed solitary ocular lymphoma [PSOL], corresponding to the primary intraocular lymphoma [PIOL] of human patients) can also occur. Such tumors are considered rare in dogs.5,7,11

The clinical presentation in this case (i.e., glaucoma and lens luxation) is fairly typical for dogs with lymphoma metastatic to the eye. Clinical features may also include uveitis, retinal hemorrhage, retinal detachment, hyphema, and conjunctivitis.1,5 Most of these features were found histologically in this dog. Ocular signs may represent the initial finding in dogs with generalized lymphoma, prompting owners to take the animal to a clinician. This salmagundi of intraocular changes can mimic other primary intraocular conditions and mislead clinicians, analogous to the masquerade syndrome in people.2

Confirmation of metastasis of lymphoma to the eye(s) can be of prognostic value for dogs undergoing standard chemotherapeutic regimens. Such dogs have a lifespan only 60 – 70% as long as those without ocular metastasis. Intraocular metastasis of lymphoma to one or both globes is therefore an ominous development.1 Neoplastic lymphocytes are thought to localize initially in the anterior ciliary body and/or iris root.5 When the intraocular lymphoma is at a more advanced stage, as in this case, the anterior uvea tends to be the most severely infiltrated component, followed by the choroid.1 Median survival time in one study of 100 dogs with intraocular lymphoma was 104 days. There was no statistical difference in survival time between animals with lymphoma of T versus B cell derivation.5 Survival times in dogs with true primary intraocular lymphoma are longer (MST: 769 days) and some appear to have been cured by surgical enucleation alone.5 Survival times in dogs undergoing chemotherapy for intraocular lymphoma can be as long as one year, compared to 2-4 weeks for untreated dogs.5

There is an interesting disparity between intraocular lymphoma in dogs with multicentric T cell lymphoma relative to human patients. People with generalized T cell lymphoma rarely develop intraocular metastases.5 By contrast, a voluminous literature now exists about primary intraocular lymphoma in people, generally of B lymphocyte origin, which may also involve brain, spinal cord and/or meninges.2 These are thought to arise in a multicentric fashion in the CNS and in the retina-vitreous.

In our experience, clinicians prefer to enucleate eyes in which they suspect intraocular neoplasia rather than use cytology first to establish the identity of the tumor. Some current cytology texts provide guidelines for interpretation so that cytology and/or antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR) testing may be used more in the future following anterior chamber paracentesis.9,10 For understandable reasons, cytology is more commonly used in human ophthalmology for intraocular masses, relative to dogs or cats. It is likely in this case that cytological sampling of anterior chamber could have generated a diagnosis of lymphoma.

Contributing Institution:

Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory

1174 Snowy Range Road

Laramie, WY 82070. http://www.uwyo.edu/wyovet/

JPC Diagnosis:

Eye, uvea: Lymphoma, intermediate cell, mid-grade.

JPC Comment:

This case provides an excellent, classic example of the ocular manifestation of canine multicentric lymphoma. As the contributor notes, ocular involvement is seen in over one-third of dogs with multicentric lymphoma and is second only to enlarged lymph nodes as the most common clinical finding in canine lymphoma. Due to hematogenous spread, the uveal tract, most commonly the choroid, is affected in the vast majority of cases (97% in one large retrospective study), followed by the retina (46%), the cornea (32%), and the sclera (43%).5 As in this case, peripheral T-cell lymphoma is the most common histologic subtype encountered in the eye, followed closely by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).5

While lymphoma is the most common metastatic intraocular tumor, it is, of course, not the only one. A recent large retrospective study of 173 canine intraocular tumors found that the median age of diagnosis was 10 years, and the most commonly represented breeds included neoplasia stalwarts Labrador Retrievers and Golden Retrievers as well as mixed breed dogs.4 In this patient population, the primary multicentric malignancies were lymphoma and histiocytic sarcoma, consistent with previous reports.4 Intraocular histiocytic sarcoma is associated with a particularly short post-diagnosis survival time lending support to the view that intraocular histiocytic sarcoma is most commonly manifestation of disseminated, multicentric disease.4 Excluding the hematopoietic/multicentric tumors, hemangiosarcoma was found to be the most common metastatic intraocular tumor. Metastatic epithelial neoplasms represented in the study included mammary, pancreatic, and urothelial carcinomas.4

The moderator began discussion of this case by noting the mild edema and multifocal vascularization of the cornea, which had been overlooked in initial descriptions of the slide. The moderator cautioned participants to examine all tissues present, particularly when, as in this case, the slide is dominated by one major, attenting-grabbing lesion. And while a dramatic lesion, conference participants made relatively short diagnostic work of this neoplasm. Participants briefly discussed the possibility of melanoma, which the moderator noted would, in dogs, typically be nodular rather than the diffusely thickend iris examined in section. The common top differential was lymphoma, confirmed by the diffuse positive cytoplasmic immunoreactivity of neoplastic cells for CD3.

Conference discussion moved to the clinical diagnosis of glaucoma and the lack of convinving evidence of glaucoma on histologic examination. The moderator noted that degeneration of the retinal ganglion cell layer is a key histologic hallmark of glaucoma that was absent in the examined section. Participants remarked on the tombstoning and hypertrophy of the retinal pigmented epithelium which suggests that the observed retinal detachment is unlikely artifact, though a cause for the detachment was not apparent histologically.

The moderator noted that presence of intraocular lymphoma automatically makes for stage V disease under the WHO lymphoma guidelines. This is a codification of the lymphoma dogma of “if it’s in the eye, it’s everywhere.” The moderator noted that this view is changing, pointing to the presence of presumed solitary ocular lympoma [PSOL] which can often be successfully treated by enucleation.

Discussion ended with a brief survey of unique feline ocular neoplasias, including feline diffuse iris melanoma. The moderator noted that the examined section would be suspicious for this entity if the patient were a cat as the histological appearance is similar. Conference participants also discussed feline post-traumatic ocular sarcoma, an aggressive neoplasm that is locally invasive with metastatic potential. The sarcoma arises from metaplastic lens epithelium and can invade extraorbital tissues, typically via the limbus or the optic nerve.

References:

- Carlton WC, Hutchinson AK, Grossniklaus HE. Ocular lymphoid proliferations. In: Peiffer RL, KB Simons KB, eds. Ocular Tumors in Animals and Humans. Iowa State Press;2002:379-413.

- Coupland SE, Chan CC, Smith J. Pathophysiology of retinal lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:227-237.

- Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36:564-578.

- Krieger EM, Pumphrey SA, Wood CA, Mouser PJ, Robinson NA, Maggio F. Retrospective evaluation of canine primary, multicentric, and metastatic intraocular neoplasia. Vet Ophthalmol. 2022;25(5): 343-349.

- Lanza MR, Musciano AR, Dubielzig RD, Durham AC. Clinical and pathological classification of canine intraocular lymphoma. Vet Ophthalmol. 2018;21:167-173.

- Levy-Clarke GA, Greenman D, Sieving PC, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis of intraocular metastatic T-cell lymphoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:285-295.

- Malmberg JL, Garcia T, Dubielzig RR, Ehrhart EJ. Canine and feline retinal lymphoma: a retrospective review of 12 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 2017;20:73-78.

- Miller PE, Dubielzig RR. Ocular tumors. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, Page RL, eds. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 5th ed. Elsevier;2013:597-607.

- Pate DO, Gilger BC, Suter SE, Clode AB. Diagnosis of intraocular lymphosarcoma in a dog by use of a polymerase chain reaction assay for antigen receptor rearrangement. JAVMA. 2011;238:625-630.

- Raskin RE. Eyes and adnexa. In: Raskin RE, Meyer DJ, eds. Canine and Feline Cytology. A Color Atlas and Interpretation Guide. 3rd ed. Elsevier;2016;408-429.

- Wiggans KT, Skorupski KA, Reilly CM, Frazier SA, Dubielzig RR, Maggs DJ. Presumed solitary intraocular or conjunctival lymphoma in dogs and cats: 9 cases (1985–2013). JAVMA. 2014;244:460-470.

- Krieger EM, Pumphrey SA, Wood CA, Mouser PJ, Robinson NA, Maggio F. Retrospective evaluation of canine primary, multicentric, and metastatic intraocular neoplasia. Vet Ophthalmol. 2022;25(5): 343-349.