Signalment:

Approximately 10 days later, mortality started with 5- 10 dead kits per day. Mortality was concentrated in 2 of 8 barns and the mahogany mink were primarily affected. Affected mink kits had wet heads and were screaming, seizuring before dying. This producer mixes his own feed on farm and in the last week, had a feed change to fish, chicken and processed meats. Only the chicken is fresh daily, the other protein sources are frozen. As of a week ago, antibiotics (CSP 250) were mixed in the feed. The older mink are fine.

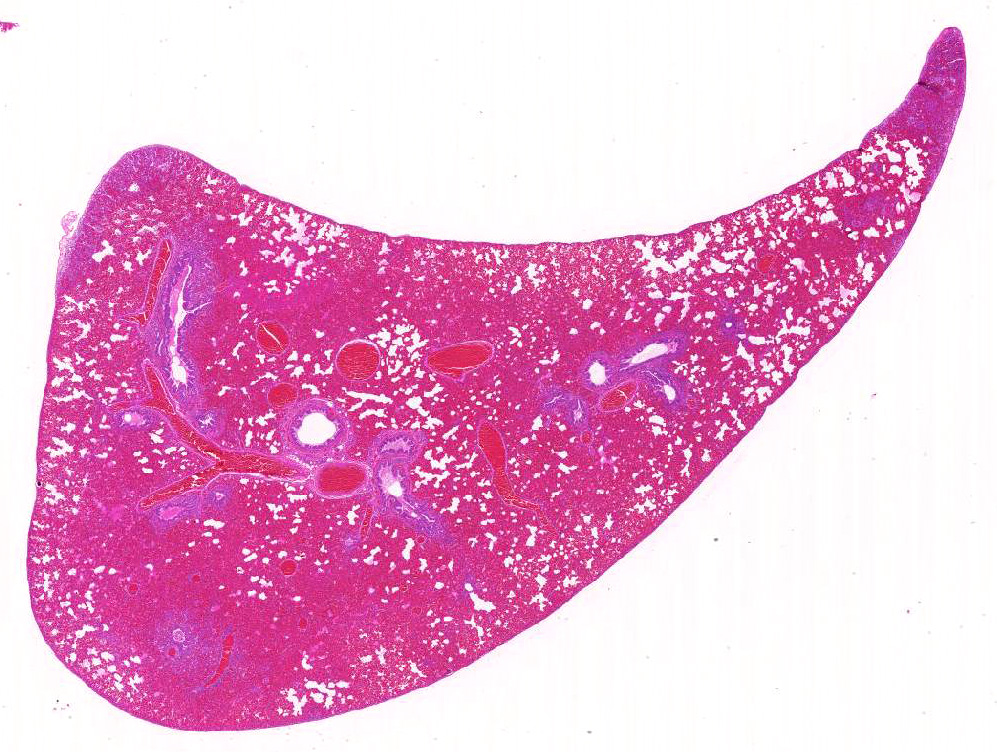

Gross Description:

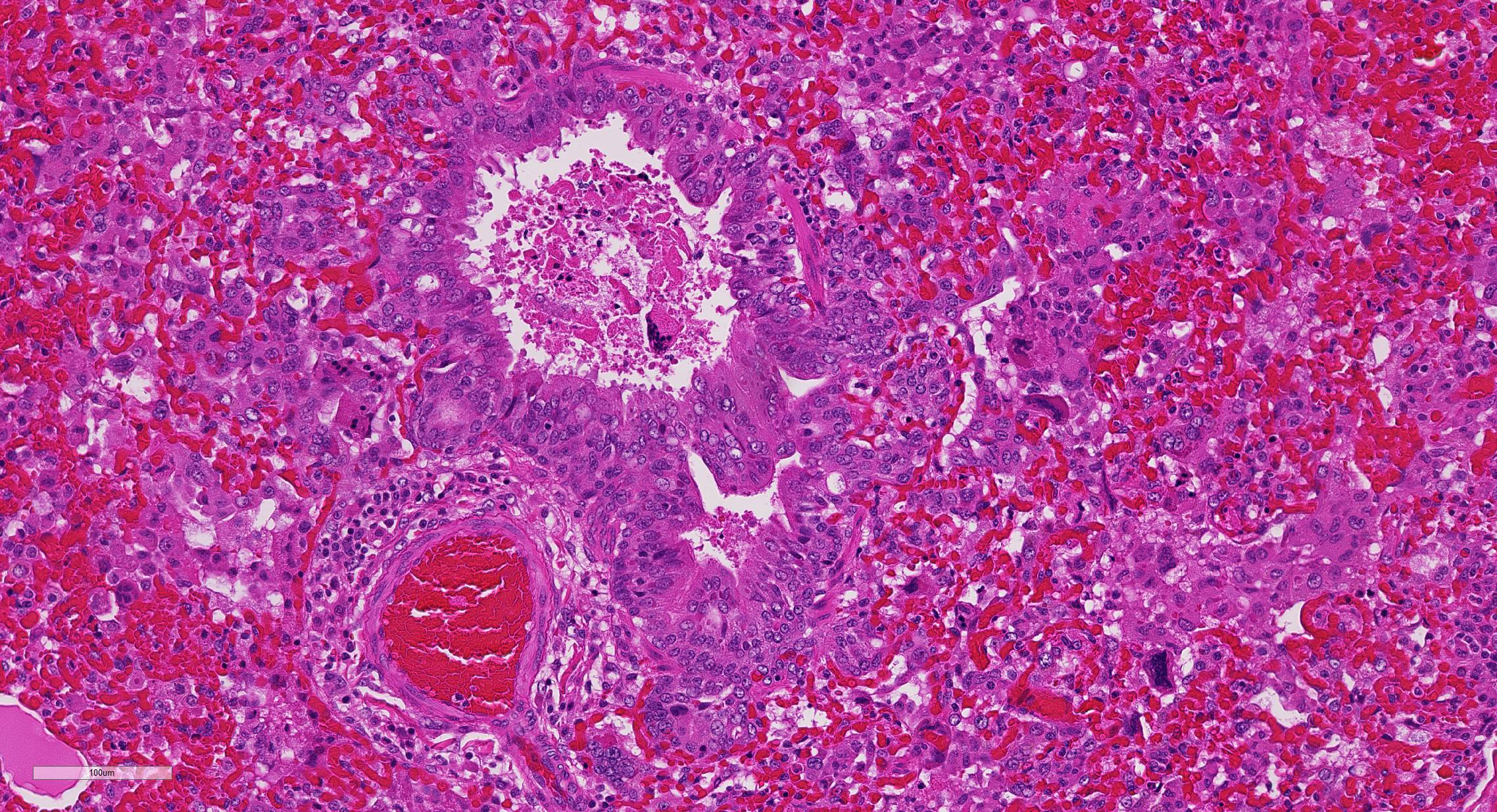

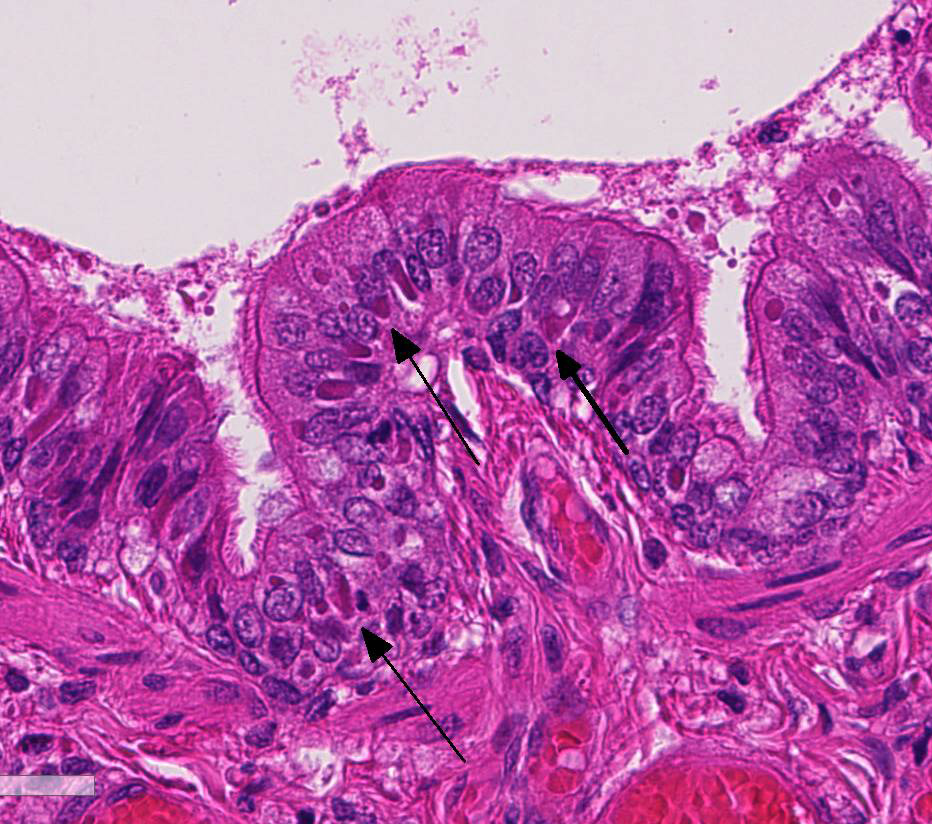

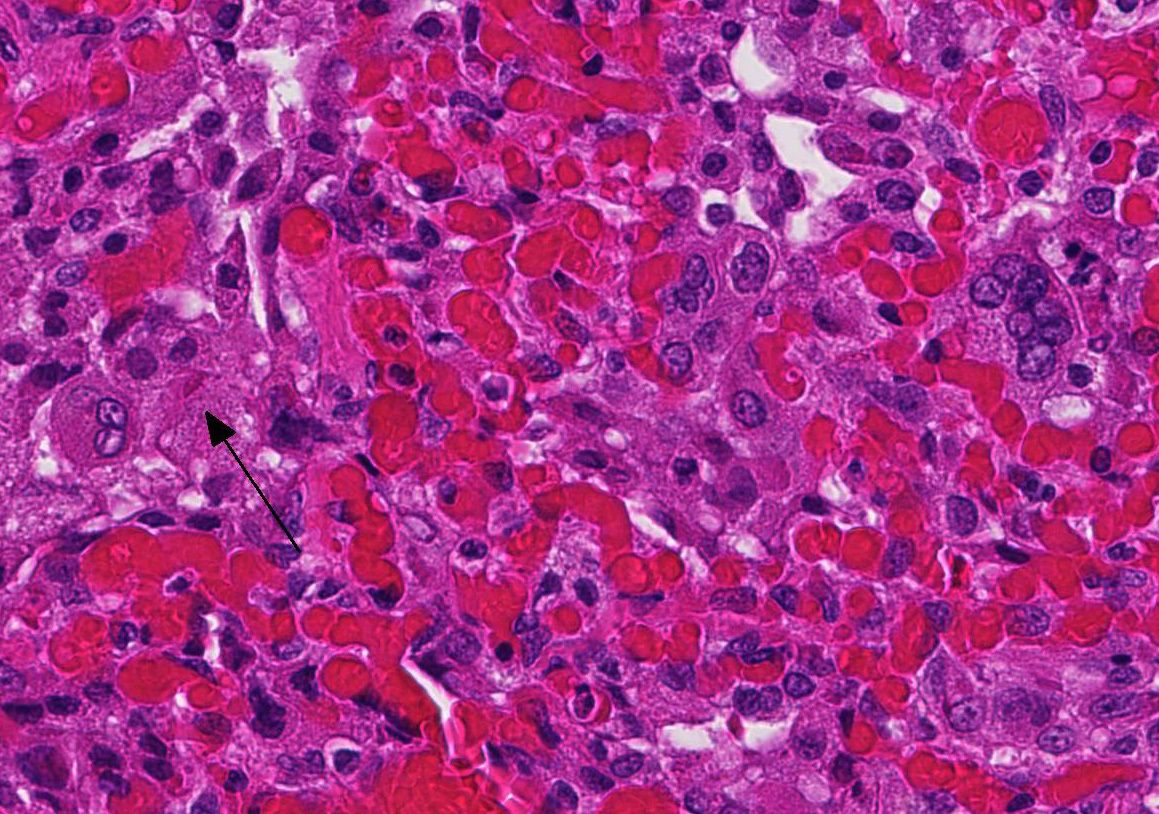

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

2. Proliferative bronchitis, bronchiolitis and multifocal histiocytic pneumonia with eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions.

3. Very mild acute suppurative bronchitis, bronchiolitis and pneumonia

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Routine vaccination of kits via subcutaneous injection using a multivalent vaccine including canine distemper virus is typically carried out after weaning.4 Some producers will also revaccinate the mature females and males being retained for breeding at this time (J Mitchell, personal communication). On this farm, the 4-way combination vaccine was split and the mink kits were immunized by subcutaneous injection for mink enteritis virus, Clostridium botulinum Type C and Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 6 weeks of age. Four to six weeks later, the kits were given the canine distemper virus portion of the vaccine by aerosol spray, however, as the vaccine is meant to be given by subcutaneous injection it is likely the mink kits were not sufficiently immunized against canine distemper virus and subsequently developed clinical disease.

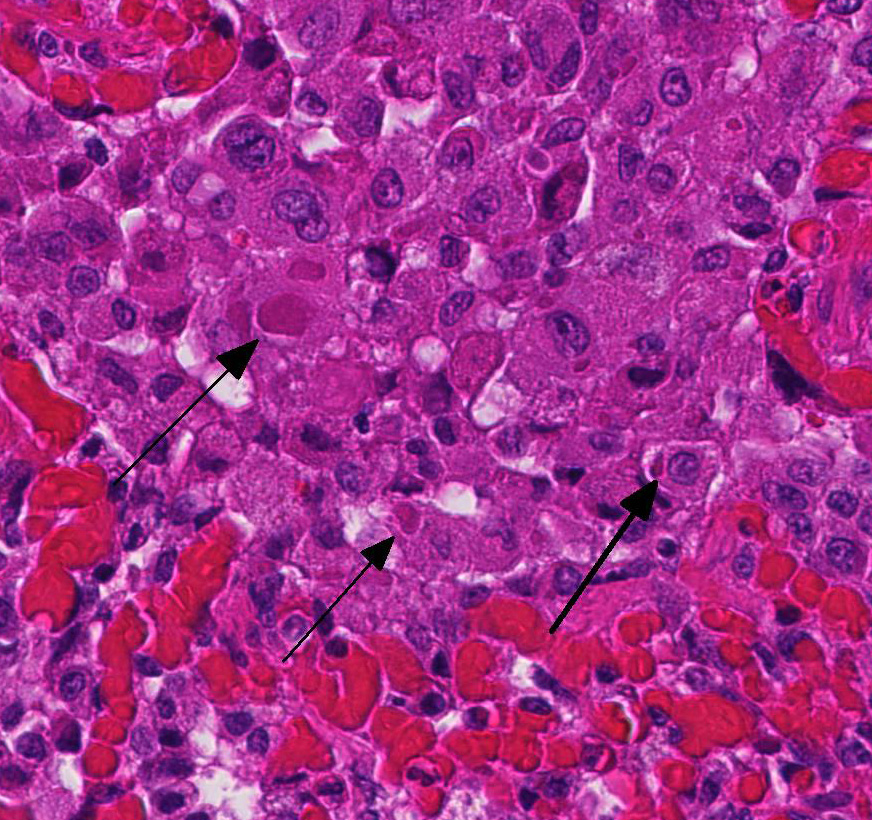

At necropsy, the most consistent lesions were identified in the lungs with pro-liferative bronchitis and bronchiolitis and variable numbers of large rectangular eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions identified in bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. Low numbers of multinucleated cells in alveoli occasionally also contain in-tracytoplasmic inclusions. Small accum-ulations of neutrophils were aggregating in small airways and secondary bacterial bron-chopneumonia is reported to commonly occur.4 The diagnosis of CDV in these individuals was confirmed with IHC.

In experimental infections with the virus given by injection, young mink are reported to develop reddening of the skin progressing to dermatitis, conjunctivitis and nasal dis-charge, but dyspnea is uncommon.4 How-ever, histologically, pulmonary lesions are common and the intracytoplasmic and intranuclear viral inclusions are most often present in the respiratory or bladder ep-ithelium.4 Viral inclusions are not identified in the transitional epithelium of the bladder in this case, despite the tremendous numbers visible in the lung tissues.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Like all paramyxoviruses, CDV contains six structural proteins: nucleocapsid (N), phospho (P), large (L), matrix (M), hem-agglutinin (H), and fusion (F) protein. The viral envelope contains H, used for attachment to the host cell receptor, and F, required for entry and syncytia formation. In this case, syncytial cells are occasionally present within bronchioles and alveoli.1,6

CDV is typically transmitted via inhalation of infected aerosols.3,4 The virus enters macrophages, lymphocytes, and dendritic cells via the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) receptor binding to H viral protein within the first day of infection.1,6 The virus spreads to local lymph nodes and other lymphoid organs within two to five days post infection. Primary viral replication in the lymphoid tissues leads to severe immunosuppression and viremia. About eight to ten days post-infection, CDV disseminates to several epithelial tissues (respiratory, intestinal, and urinary) and the central nervous system. The virus uses epithelial cell receptor nectin-4 to gain entry into epithelial cells.1,4,6

Unfortunately, in this case, the conference participants had difficulty assessing the alveolar septal changes due to poor insufflation of the lung. However, con-ference participants easily identified numerous intracytoplasmic viral inclusions within histiocytes and the markedly hyperplastic bronchiolar epithelium. In addition, some recognized rare intranuclear inclusions. CDV is unique because it causes both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions.3,7,8 Given that CDV is an ssRNA virus that requires RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex present only in the cytosol to replicate, the presence of int-ranuclear inclusions is initially con-founding.7 However, CDV infection induces the cellular stress response which causes elevated expression of heat shock proteins. These proteins translocate viral nucleocapsid (N) proteins from the cytoplasm into the nucleus as part of the normal host cell response to cellular stress. Under normal circumstances, the N protein would be too large to pass through nuclear pores.7 N proteins form the basis for nuclear body formation, and propagation of viral nuc-leocapsids. These particles eventually partially, or completely fill the nucleus resulting the in the formation of the intranuclear inclusion body visible by light microscopy.7,8

The contributor mentions the wide range of species now infected by CDV and related viruses. Additionally, lethal outbreaks in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques ori-ginating in China have been documented within the last decade.

References:

2. Budd J. Distemper. In: Infectious diseases of wild mammals. 1st ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press; 1970:36-49.

3. Caswell J, Williams K. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016: 574-575.

4. Hunter DB. Respiratory System of Mink. In: Hunter B, Lemieux N, eds. Mink: Biology, Health and Disease. Guelph, Ontario: Graphic and Print Services, University of Guelph; 1996:13-1 13-15.

5. Kuipel M, Perpinan D. Viral Diseases in Ferrets. In: Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley Blackwell; 2014:439-450.

6. Noyce R, Depeut S, Richardson C. Dog nectin-4 is an epithelial cell recepotor for canine distemper virus that facilitates virus entry and syncytia formation. Virology. 2013;436:210-220.

7. Oglesbee M. Intranuclear inclusions in paramyxovirus-induced encephalitis: ev-idence for altered nuclear body differen-tiation. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;84:407-415.

8. Oglesbee M, Krakowa S. Cellular stress response induces selective intranuclear traf-ficking and accumulation of morbillivirus major core protein. Lab Invest. 1993; 68:109-107.

9. Williams ES. Canine Distemper. In: Williams ES, Barker IK, eds. Infectious diseases of wild mammals. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press; 2001:50-59.

10. Qiu W1Zheng Y, Zhang SFan Q, Liu H, Zhang F, Wang W, Liao G, Hu R. Canine distemper outbreak in rhesus monkeys, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;17(8):1541-3.

11. Sakai K1Nagata N, Ami Y, Seki F, Suzaki Y, Lethal canine distemper virus outbreak in cynomolgus monkeys in Japan in 2008. 2013