WSC 2023-2024, Conference 16, Case 3

Signalment:

13-year-old Appaloosa-cross mare (Equus caballus)

History:

The horse presented with petechiae and edema of the upper lip and appeared to be rubbing the area. The animal was treated but did not improve. The horse was found down two days later with icterus and died shortly afterwards.

Gross Pathology:

The horse was icteric. The liver was small and collapsed or flattened.

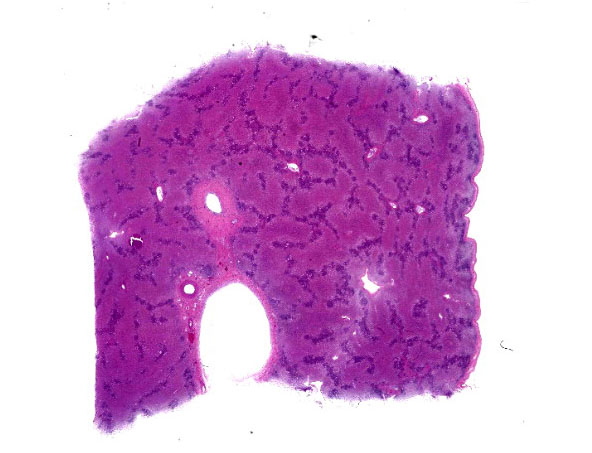

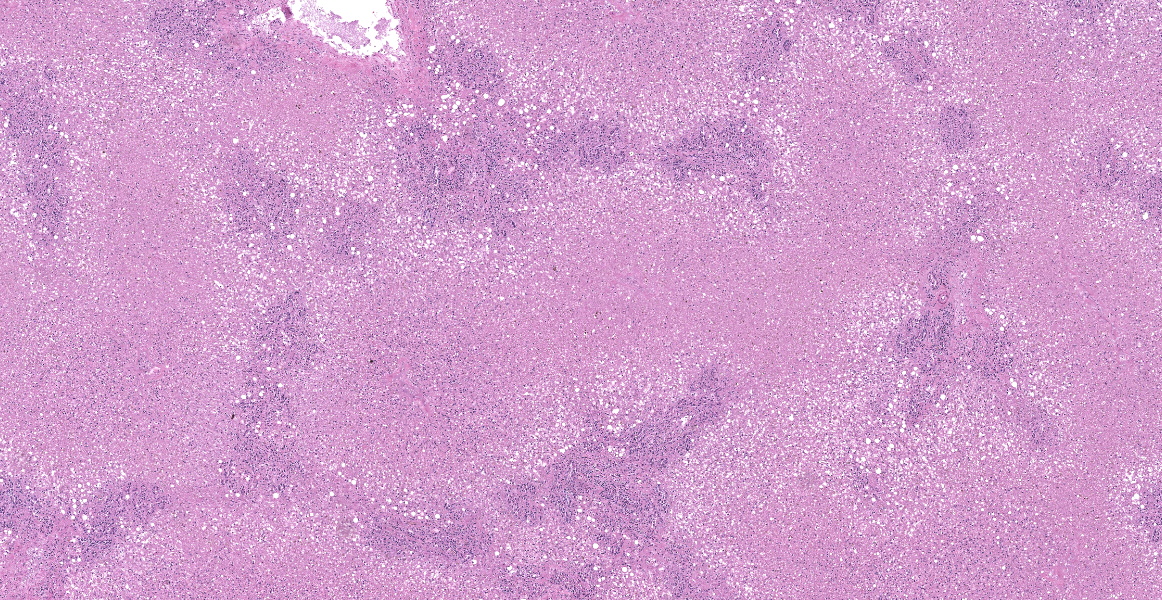

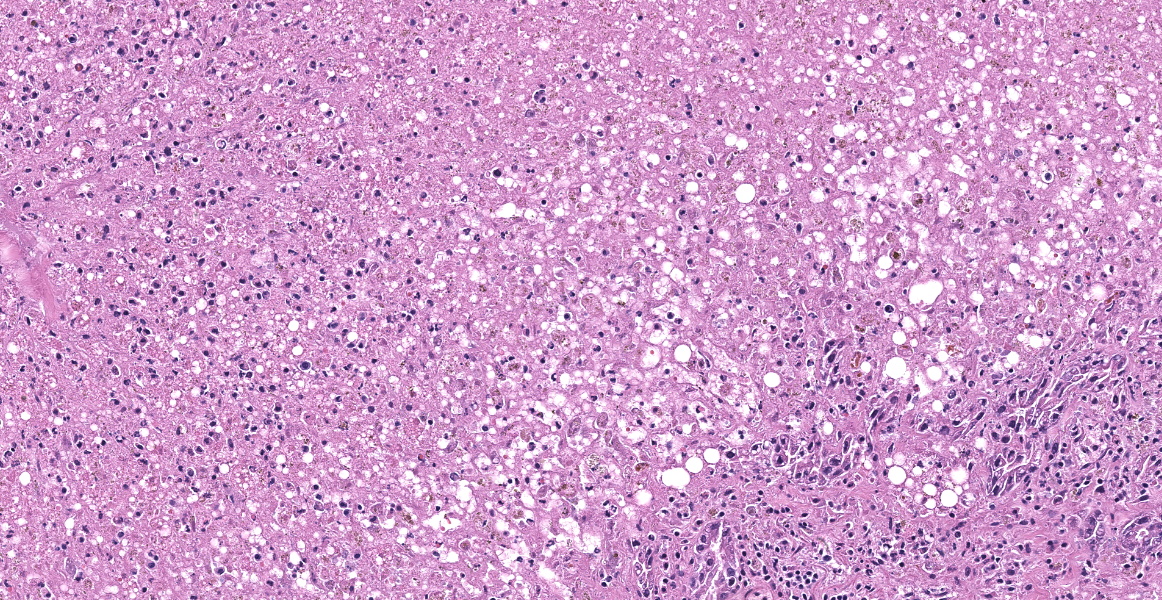

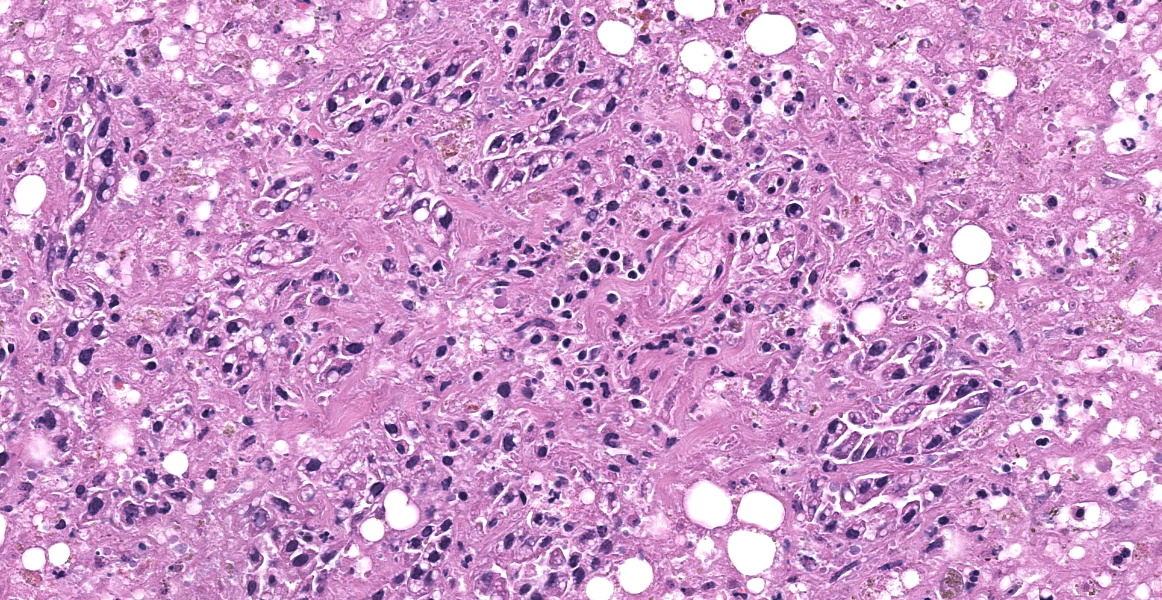

Microscopic Description:

The tissue submitted is liver. There is centrilobular to massive hepatocellular necrosis. Portal triads have bile duct hyperplasia, mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, and fibrosis with partial bridging between portal triads.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Massive hepatocellular necrosis

- Mild, chronic lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis

Contributor’s Comment:

This is a case of equine serum hepatitis, also known as Theiler’s disease. The histologic features of this disease are unique and diagnostic. There is an acute centrilobular to massive hepatocellular necrosis and a chronic portal hepatitis. Grossly, the liver is small and collapsed and sometimes flabby or flaccid.

Equine serum hepatitis was first described by Theiler early in the 20th century. The disease was associated with the use of various biologics containing equine serum, usually vaccines, and occurred 1-3 months following the use of these products.1,3 However, many cases occurred that had not received equine serum. The cause of the disease is now thought to be viral.2

Contributing Institution:

College of Veterinary Medicine

Virginia Tech

www.vetmed.vt.edu

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Necrosis, massive, diffuse, with stromal collapse and hepatocellular lipidosis.

JPC Comment:

Theiler’s disease was first described in 1919 by South African veterinarian Sir Arnold Theiler after hundreds of horses acutely died of hepatitis after being vaccinated against African Horse Sickness.2 Since first described, Theiler’s disease has been documented worldwide in horses treated with a variety of biologics, including tetanus antitoxin, botulinum antitoxin, antiserum against Streptococcus equi, and equine plasma, though for the past 50 years, disease has been most commonly associated with administration of tetanus antitoxin.2 A variety of potential causes have been investigated and proposed as the etiologic agent of Theiler’s disease, most notably a pegivirus named Theiler’s Disease-Associated Virus (TDAV); however, the currently accepted etiologic agent is a parvovirus, named equine parvovirus hepatitis virus (EqPV-H), which was discovered, isolated, and characterized in 2018.1,2

A typical case presentation of Theiler’s disease involves rapidly progressive symptoms of lethargy, anorexia, and jaundice 2-3 months following the administration of blood products; clinical pathology abnormalities include elevated serum levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin.1 Some horses may have fever and central nervous system signs such as cortical blindness, ataxia, behavior changes, or coma.1 Histologically, Theiler’s disease is characterized by massive hepatocellular necrosis, as illustrated nicely by this case. Mortality rates between 50% and 90% are reported.1 Experimental studies of EqPV-H have revealed the virus to be endemic in the United States,

parts of Europe, and China, with estimated prevalence of 2.9-17%, with up to 54% prevalence on farms with recent outbreaks of Theiler’s disease.2 The virus has been shown to be transmitted via stem cell therapy for orthopedic injuries and by oral inoculation with viremic serum; vertical transmission appears to be minimal.2 EqPV-H is shed in oral and nasal secretion and in feces, leading to potential environmental accumulation of this hearty virus.2 Research into effective biosecurity measures to minimize EqPV-H transmission is ongoing.

Participants felt that slide description in this case was a challenge as virtually nothing was left to describe! On subgross evaluation, however, participants noted the wrinkling of the liver capsule and the irregular distances between central veins and portal triads throughout the section, both indicators of microhepatica due to massive necrosis/stromal collapse. Dr. Pesavento contrasted this presentation with liver shunting, which typically presents with capsule wrinkling but relatively constant central vein to portal triad distances.

Even without the subgross suggestion of microhepatica, however, the massive hepatocellular necrosis evident on histological examination is characteristic of Theiler’s disease, which should be included in every differential list for massive hepatic necrosis in a horse. Evaluation of a Masson trichrome illustrated some fibrosis, but participants felt that the amount of fibrosis was likely normal for a 13-year-old horse. Fibrosis is generally not a histologic feature of Theiler’s disease as animals typically do not live long enough to develop it.

Participants were surprised by the reticulin stain in this case, which looked relatively normal. Similar to the previous case, the reticulin framework remained intact despite the massive necrosis, once again highlighting the hepatocellular-centric nature of this disease.

Dr. Pesavento discussed the current understanding of Theiler’s disease which, in a testament to the rapid advancement of scientific knowledge, has changed and solidified since this case was originally submitted to the Wednesday Slide Conference. At that time, the current theory was that a pegivirus, termed Theiler’s disease-associated virus (TDAV) was responsible for the disease; however, researchers were skeptical of this claim from the outset as pasteurization of the serum products implicated in the transmission of Theiler’s disease should have incapacitated TDAV. Further research lead to the discovery EqPV-H, a parvovirus that can withstand typical pasteurization temperatures, and subsequent studies have established a strong correlation between EqPV-H and Theiler’s disease.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis was relatively short as the hepatocellular necrosis was glaring and all-encompassing. Participants noted the periportal lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis described by the contributor, but chose to omit it from the JPC diagnosis to emphasize the necrosis-driven pathogenesis.

References:

- Chandriani S, Skewes-Cox P, Zhong W, et al. Identification of a previously undescribed divergent virus from the Flaviviridae family in an outbreak of equine serum hepatitis. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2013; 10(15):E1407-E1415.

- Divers TJ, Tennant BC, Kumar A, et. al. New parvovirus associated with serum hepatitis in horses after inoculation of common biologic product. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(2):303-310.

- Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed, vol 2. Elsevier-Saunders;2007:343-344.