CASE I: D21-018285 (JPC 4167865)

Signalment:

10-month old, male castrated, European ferret (Mustela putorius furo)

History:

The ferret initially presented to the Zoological Medicine Service for an acute onset of inappetence, sneezing, coughing, and lethargy. The animal was laterally recumbent unless propped up and was febrile (106.4 °F). Clear, serous discharge came from both nostrils, the animal was sensitive to abdominal palpation, and a firm semi-mobile 1.5 cm mass was felt in the skin of the dorsum between the scapulae. No wheezes or crackles were heard on auscultation. The animal was treated empirically with Clavamox and enrofloxacin for a suspected abscess.

The ferret re-presented the same day to the Emergency Service. At re-presentation, his temperature was 105.7 °F. Full body radiographs were performed and mild splenomegaly and trace peritoneal effusion were seen. CBC showed leukocytosis (WBC 18,000/ µL). A splenic fine needle aspirate was performed and extramedullary hematopoiesis, primarily myeloid in origin, was seen. The animal was treated with cyclophosphamide, chloramphenicol, and prednisolone and improved within the first week, but acutely decompensated approximately three weeks after presentation and died.

Gross Pathology:

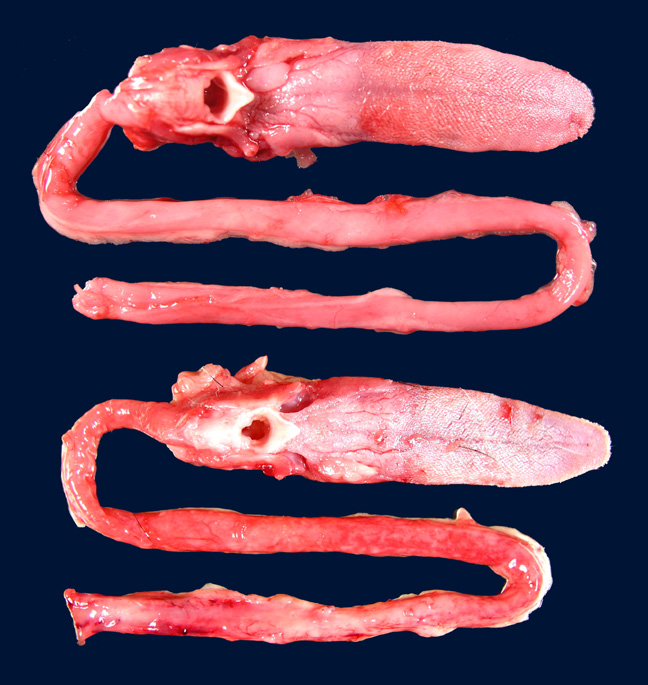

All skeletal muscles were mildly to moderately atrophic; the temporal muscles and muscles of the proximal hind limbs appeared most severely affected. The spleen was moderately enlarged, diffusely light brown, and firm. Numerous pinpoint hemorrhages were present along the adventitia of the esophagus throughout its entire length.

Laboratory Results:

None submitted.

Microscopic Description:

Skeletal muscle; esophagus (muscularis propria), larynx: Multifocally throughout the section, skeletal muscle fibers are separated, expanded, and replaced by moderate to large numbers of degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils and macrophages, which dissect through and expand the fascia and endomysium. Large infiltrates of these inflammatory cells obliterate the architecture of the muscle fibers. Remaining entrapped islands of myocytes are frequently degenerate with cell swelling or shrinking, hypereosinophilia, fragmentation of sarcoplasm, and loss of cross striations.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Skeletal muscle: Myositis and fasciitis, pyogranulomatous to suppurative, multifocal to coalescing, severe with abundant myocyte degeneration

Spleen (not submitted): Extramedullary hematopoiesis, diffuse, marked

Contributor?s Comment:

The histologic changes in the skeletal muscle of this animal are consistent with disseminated idiopathic myofasciitis (DIM), an inflammatory myopathy in ferrets.

First described by Garner et al in 2007, gross findings of DIM include whole body muscle mass loss, esophageal mottling, white streaks in muscles, lymphadenomegaly, and splenomegaly. Histologic lesions consist of suppurative to pyogranulomatous inflammation in muscle, fascia, and adipose throughout the body with associated atrophy, as well as myeloid-predominate extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen.3,5 Inflammation in the muscularis of the esophagus with sparing of the mucosa is considered an important histologic lesion in DIM.2 Affected ferrets are generally young (<18 months), however DIM has been reported in ferrets as young as 4 months and as old as 24 months5, with no sex predilection.

Clinical signs include acute onset of severe pyrexia, lethargy, pain, paresis, and recumbency. Additional reported clinical signs include inappetence, dehydration, lymphadenomegaly, serous nasal or ocular discharge, and diarrhea.3,5 Clinical pathology may show leukophilia due to mature neutrophilia, increases in ALT and glucose, and mild hypoalbuminemia. Creatinine kinase, generally associated with muscle damage, is not elevated. Animals generally decline until death or euthanasia and the disease is resistant to attempts at treatment, which has included antibiotics, steroids, NSAIDs, and immune modulators.5

The inciting cause of DIM is not known. Histologic, immunohistologic, and electron microscopy testing for infectious etiologies, including fungi, bacteria, and protozoa such as Sarcocystis neurona, Toxoplasma gondii, and Neospora caninum have been unrewarding.3,5 An association with the Fervac-D canine distemper vaccine was considered; however, this vaccine is no longer produced, and more recently affected ferrets have been vaccinated with several different distemper vaccines, including Distox-Plus, Distem-R TC, Purevax, and Galaxy-D.3,5 A heritable component is being considered, as some forms of inflammatory myositis in humans and dogs are inheritable5, and immune mediated myositis (IMM) in horses is suspected to be inheritable as well due to its prevalence in reining and cow bred Quarter Horses and Quarter Horse outcross breeds such as the American Paint Horse and Appaloosa.1,4

Immune mediated inflammatory myopathies exist in several other species; however, the inflammation in these diseases is generally mononuclear, particularly lymphocytes, in contrast to the suppurative to pyogranulomatous inflammation seen in ferrets with DIM. Horses with IMM are generally between 8 and 17 years old, and

39% have been recently exposed to a suspected immune trigger such as

Streptococcus equi or other respiratory viral infection, or vaccination.1 Horses with IMM have lymphocytic infiltration of myocytes and frequently lymphocytic vascular cuffing, with the epaxial and gluteal muscles most commonly affected and other muscles generally being spared.1 In dogs, immune-mediated myositis may be confined to the masticatory muscles or may be widespread as a polymyositis (PM). Masticatory myositis results from autoantibodies to type 2M myosin, a myosin isoform that is only found in the masticatory muscles, and inflammation generally consists of eosinophils and lymphocytes.6 PM in dogs is most common in large breed dogs, particularly German Shepherds. A breed associated PM also occurs in Newfoundlands with primarily lymphocytic inflammation.6 In humans, immune mediated polymyositis results from development of autoantibodies to muscle components. Human PM consists primarily of non-suppurative inflammation, predominantly T lymphocytes and macrophages.3

Contributing Institution:

Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Department of Diagnostic Medicine/Pathobiology

Ksvdl.org

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Larynx and esophagus: Rhabdomyositis, neutrophilic, chronic-active, diffuse, severe, with myofiber atrophy.

2. Perilaryngeal soft tissues: Cellulitis, neutronphilic, chronic-active, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of disseminated idiopathic myofasciitis (DIM) in ferrets, an inflammatory myopathy with a high mortality rate, no sexual predisposition, and predominantly affects ferrets less than 18 months of age.5

Although astute diagnosticians may suspect DIM based on the previously noted clinical signs and clinical pathology abnormalities, definitive antemortem diagnosis requires the biopsy of skeletal muscle, preferably from 2-3 locations given DIM?s multifocal distribution. Recommended sites include the lumbar, pelvic limb, shoulder, or temporal regions. Essential tissues collected from necropsies include esophagus, skeletal muscle, and heart, although lesions may be observed other tissues, such as the larynx in this case; therefore a comprehensive set of tissues should ideally be collected. Finally, given the pathogenesis is unknown, it is recommended to collect paired tissue samples that may be frozen and used in future studies.5

Two diseases with similar clinical and pathologic features that are also commonly fatal in this species include ferret systemic coronavirus infection and mycobacteriosis.2

Ferret systemic coronavirus (FSCV) infections were first recognized around 2003, during the same time period as initial cases now known as DIM were reported. FSCV causes gross and histologic lesions identical to those of feline infectious peritonitis, which arise as the result of systemic pyogranulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and necrosis that predominantly targets visceral organs and lymph nodes. Young adult ferrets are most commonly affected and clinical signs may include intra-abdominal masses, lymphadenomegally, vomiting, diarrhea, inappetance, dyspnea, CNS signs, and mild ascites (uncommon). Gross findings include white to tan nodules on the serosa of thoracic and abdominal organs, as well as within the parenchyma and lymph nodes. Biopsy of affected tissue, typically lymph node or mesentery, is necessary for antemortem diagnosis. Immunohisto-chemical reagents developed for FIP may be utilized for the diagnosis of FSCV due to cross-reactivity. Interestingly, analysis FSCV?s spike protein indicates the virus is more closely related to ferret enteric coronavirus (etiologic agent of epizootic catarrhal enteritis) than feline coronaviruses, despite the nearly identical gross and histologic lesions shared with FIP.2

In regard to mycobacteriosis, ferrets appear to be particularly susceptible to human, bovid, and avian strains of mycobacteria and serve as reservoir hosts, most notably in New Zealand where transmission of Mycobacterium bovis from feral ferrets to humans and sheep is of concern. Mycobacterium avium is the most common etiology identified in the United States and is typically associated with granulomatous gastroenteritis, lymphadenitis, otitis, and meningoencephalitis with large numbers (i.e. multibacillary) of acid-fast bacteria within macrophages. Atypical mycobacteriosis may also occur, with very few bacteria (i.e. paucibacillary), most commonly being found extracellularly within areas of necrosis or surrounded by inflammatory cells. Depending on the tissue affected, clinical signs may include nasal discharge, head tilt, circling, vomiting, diarrhea, and enlarged visceral and peripheral lymph nodes. As with DIM and FSCV, antemortem diagnosis requires biopsy of affected tissue, with subsequent diagnostics including acid-fast stains, PCR, and culture.2

Given mycobacteriosis shares some similar clinical and pathologic features with DIM and FECV, one should consider risk of potential zoonotic infection during tissue collection and handing in cases suspected of the two latter entities.2 Additional sections submitted with this case were subjected to a battery of stains including acid-fast, Gram, Grocott?s methenamine silver, and periodic acid-Schiff. No infectious agents were identified, further supporting the diagnosis of DIM.

Conference participants discussed the temporal characterization of inflammation in this case given neutrophilic inflammation is generally associated with an acute process. It is unknown why neutrophils are the predominant inflammatory cell associated with DIM despite being a chronic process. However, histologic features such as skeletal muscle atrophy and fibrosis are also common features of DIM and consistent with a chronic inflammatory process. Therefore, conference participants favored the temporal modifier of "chronic-active".

References:

1. Durward-Akhurst SA, Valberg SJ. Immune-Mediated Muscle Diseases of the Horse. Vet Pathol. 2018 Jan;55(1):68-75.

2. Garner MM . ?Osis,??itis,? and virus: differentiating mycobacteriosis, disseminated idiopathic myofasciitis, and systemic coronavirus in the domestic ferret. In: North American Veterinary Community Conference Proceedings. Orlando (FL), 2011.

3. Garner MM, Ramsell K, Schoemaker NJ, et al. Myofasciitis in the domestic ferret. Vet Pathol. 2007 Jan;44(1):25-38.

4. Lewis SS, Valberg SJ, Nielsen IL. Suspected immune-mediated myositis in horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2007 May-Jun;21(3):495-503.

5. Ramsell KD, Garner MM. Disseminated idiopathic myofasciitis in ferrets. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2010 Sep;13(3):561-75.

6. Van Vleet JF, Valentine BA. Muscle and tendon. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th edition, vol 1. Elsevier Ltd; 2007