Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 11

20 November 2019

Charles

W. Bradley, VMD, DACVP

Assistant Professor, Pathobiology

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

4005 MJR-VHUP

3900 Delancey Street

Philapdelphia, PA, 19104

CASE I: S17-1101 (JPC 4116937).

Signalment: 4-year-old spayed female Bernese mountain dog (Canis familiaris).

History: The animal had a one year history of skin changes including multifocal alopecia, crust formation and discolorations, whose underlying cause could not be identified. The animal had been treated with high doses of dexadreson and cyclosporine, resulting in a mild and slow improvement of the skin lesions. Two weeks before death the animal started limping and a rupture of the cruciate ligament was suspected. The animal was euthanized because of the questionable prognosis of the skin lesions in combination with the cruciate rupture and recurrent episodes of fever of unknown origin (temperature >39.8°C).

Gross Pathology: On both sides of the trunk extending to the axillas and groin, on the nasal bridge, on the ears, and around the eyes and mouth, there were multiple, sharply demarcated, hairless or partially hairless areas of skin with brown to grey discoloration and crust formation. Around these hairless areas, the fur was clotted with crusty, brown material. Bilaterally adjacent to the caudal aspect of the tongue, there were red, papillary masses of soft tissue and approximately 1 x 2 x 0.5 cm observed (histologically identified as chronic-active necrotizing and suppurative inflammation with granulation tissue formation). On the left cheek, there was a pale yellow, soft mass in the subcutis (lipoma). On the right knee joint the drawer test was positive with increased mobility of the joint. The joint was filled with turbid, slightly flocculent synovial fluid and both anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments were ruptured (right sided complete cruciate ligament rupture with secondary chronic multifocal gonitis on the right side with follicle formation). The liver was markedly enlarged and displayed round edges (diagnosed histologically as steroid induced hepatopathy).

In the right cranial lobe of the lung, there was a firm, poorly demarcated structure palpable in the parenchyma. On the serosal surface of the left middle lobe, there were multiple plaque-like, sharply circumscribed, brown depositions of material observed (histologically identified as multifocal calcifications of pulmonary basal membranes with reactive histiocytic inflammation).

Laboratory results:

Ultrasound and radiography: no abnormalities detected.

Hematology/blood chemistry: no abnormalities detected

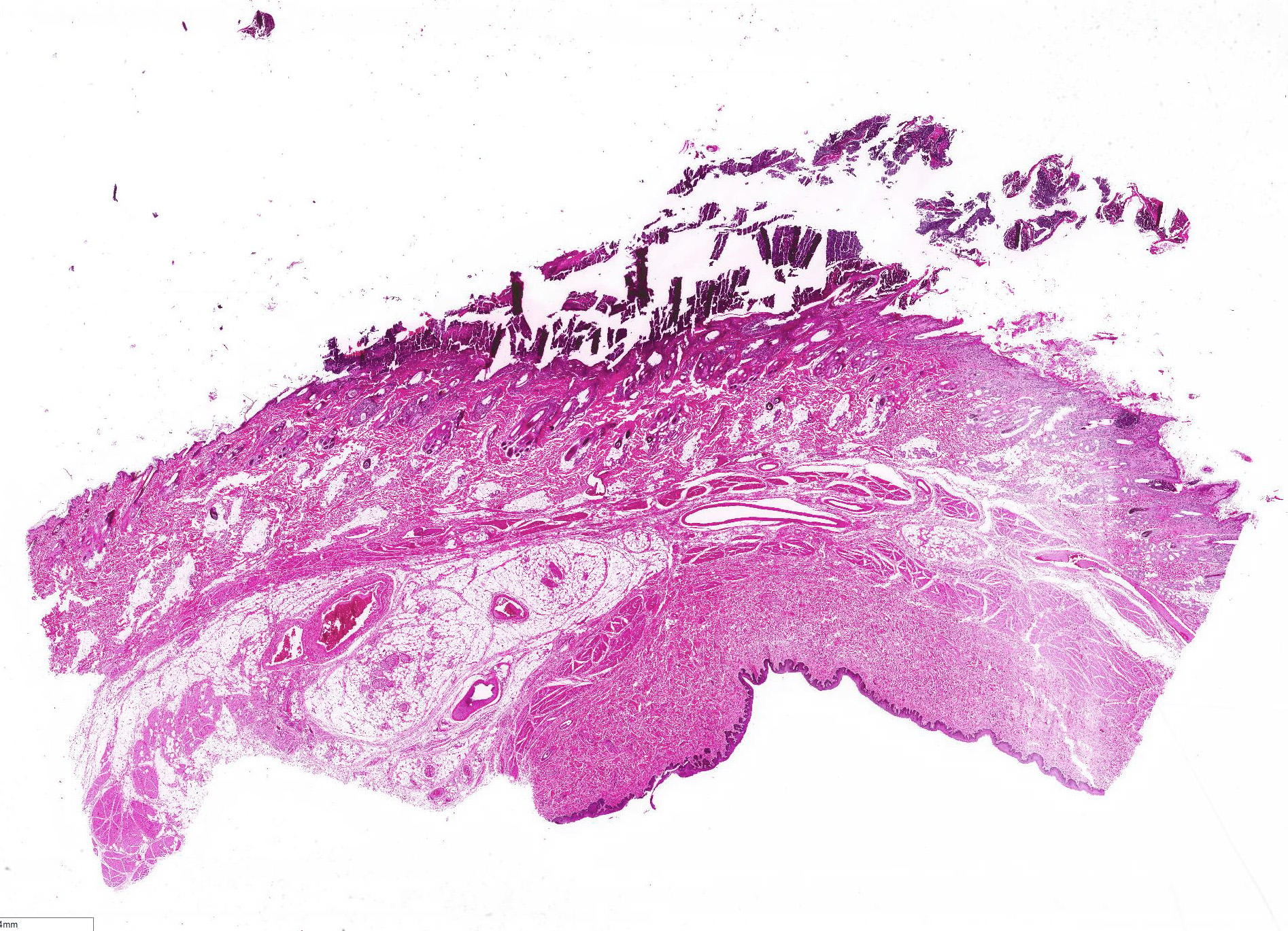

Microscopic Description:

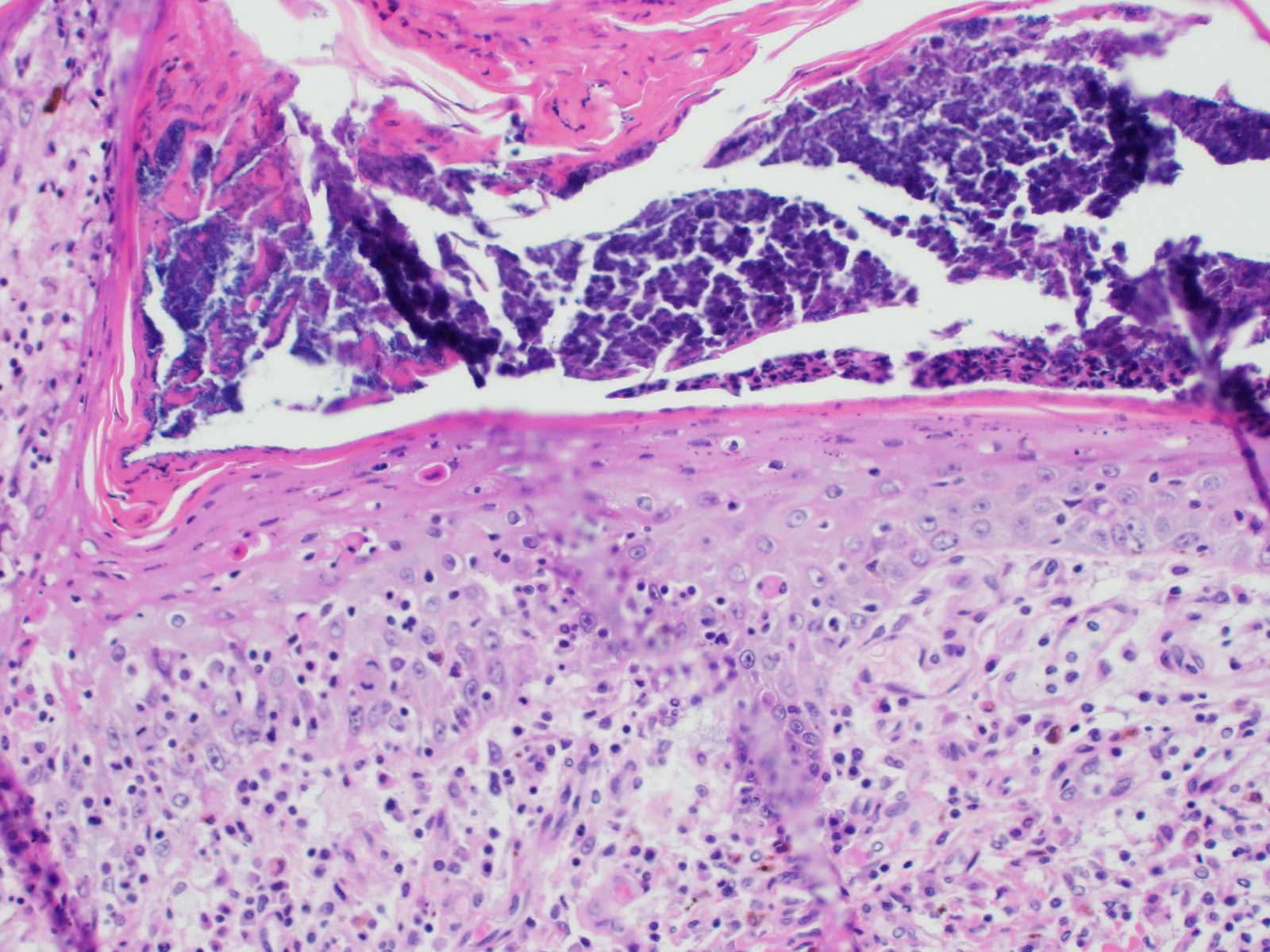

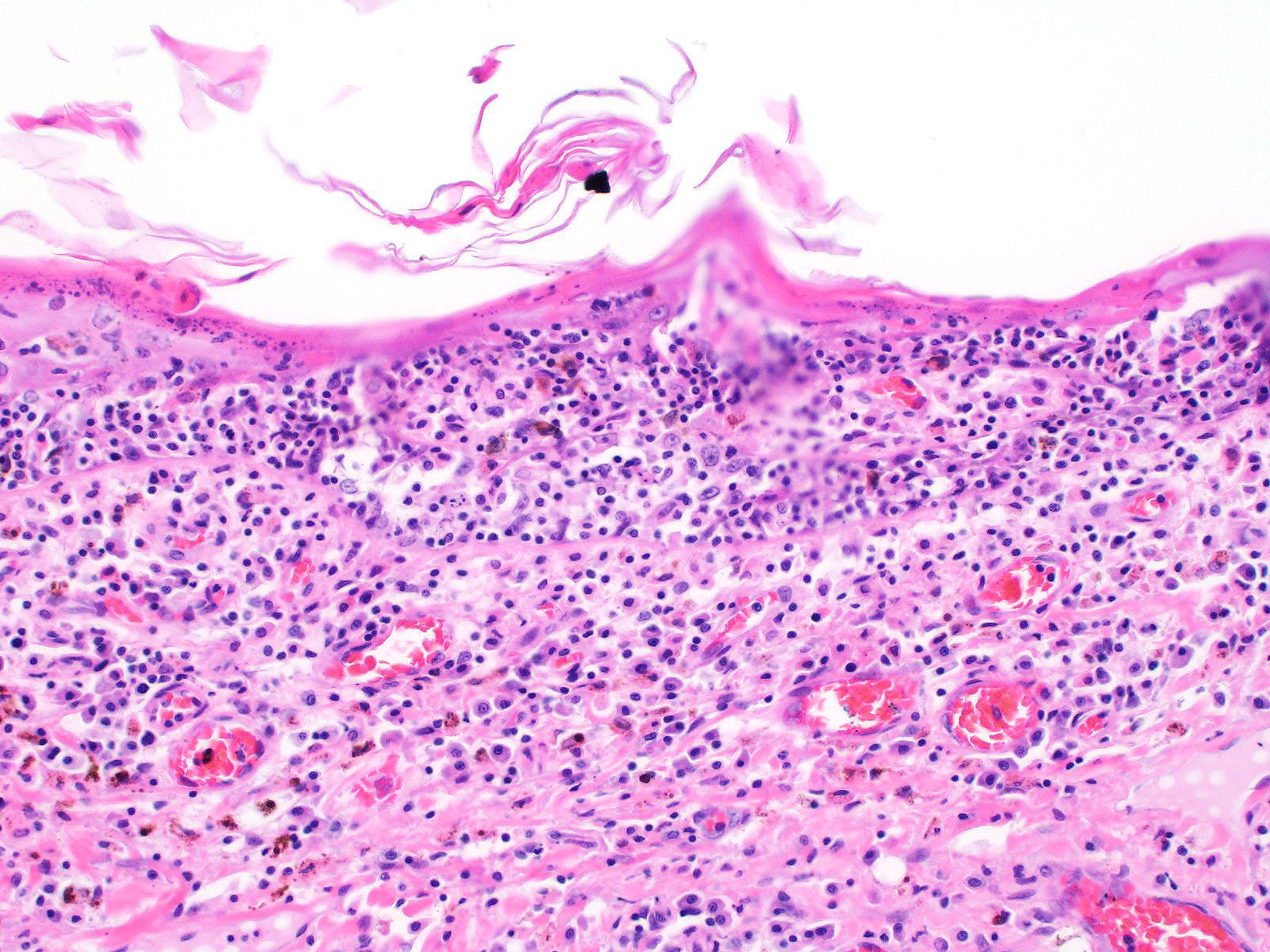

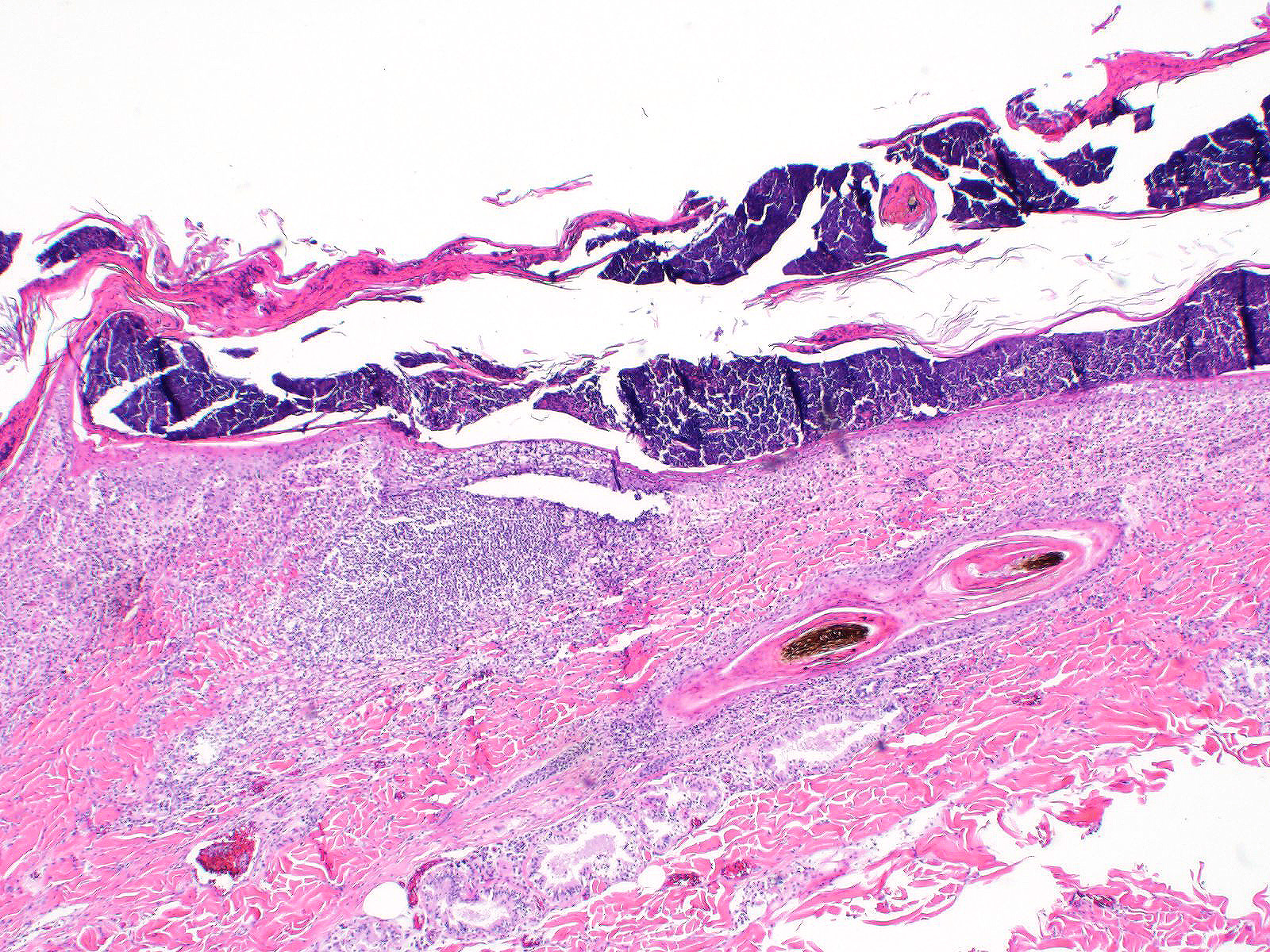

All layers of the epidermis and also the follicular infundibular epithelium contain rounded, hypereosinophilic keratinocytes with pyknotic nuclei (apoptosis). Multifocally, apoptotic keratinocytes are surrounded by lymphocytic infiltrations (satellitosis). Within the epidermis there are multifocal accumulations of neutrophils, separating the superficial from the deeper epidermal layers (interpreted as pustule formation). The superficial dermis and the dermo-epidermal junction show ribbon-like, severe infiltrations of lymphocytes, plasma cells and fewer macrophages, separating the dermo-epidermal junction into areas which are variably clearly visible or severely obscured. Lymphoid infiltrates are observed in the basal layer and macrophages containing brown pigment (melanin) are visible in the dermis (melanin incontinence). Multifocally the stratified layer is thickened and multifocally nuclei can be observed also in the superficial keratinocytes (parakeratotic and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis). Furthermore, the epidermal surface is covered by serocellular crusts and accumulations of (partially degenerate) neutrophils. In the superficial areas, low numbers of thick-walled, round structures with a clear center and approximately 5- 10 μm in diameter (interpreted as Candida spores) are observed. The neutrophilic infiltrates extend multifocally deep into the dermis or into the hair follicles (secondary suppurative pyoderma and folliculitis).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Skin, chronic multifocal to coalescing interface dermatitis, with apoptotic keratinocytes, lymphocytic satellitosis and with secondary crust formation, parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, suppurative pyoderma and folliculitis (consistent with erythema multiforme)

Contributor Comment: Erythema multiforme is a rare skin disease in dogs and cats and has also been described in horses, cattle, swine, ferrets and anecdotally in goats.3,6,7 The nomenclature and definitions of erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrosis (TEN) in veterinary literature are conflicting and therefore confusing.7,8 In human medicine, EM, SJS and TEN were considered to be different severities of the same disease. Nowadays it is accepted that EM and SJS/TEN represent separate conditions.8

The pathogenesis of erythema multiforme in animals is still poorly understood.3,6,7,8 Possible etiologies include adverse drug reactions (CADR), e.g. against sulphonamides, other antibiotics, and levamisole. Neoplasia, food (including commercial dog food and beef/soy diet), nutraceutical products and infections are reported triggers for erythema multiforme in canine patients.3,4,6,7,8 However, proven causalities by re-challenge are rare and a multicentric study revealed that only 19% of the canine EM cases were drug related.5 The histological characteristics and pattern indicate a misdirected immune response against keratinocytes, which is lymphocyte-mediated with direct cytotoxicity of target cells.6,8

Clinical lesions

In dogs, lesions are normally bilateral and involve the trunk, groin and axilla and also the inner pinna, footpads and mucocutaneous junctions.3,8 Canine and feline lesions consist of erythematous macules, papules and plaques. Lesion borders are indurated and lesion centers are clear with discolorations to cyanotic or purpuric. Central crusting of lesions is common, but in canine patients this may extend to heavily crusted and/or scaly plaques.7,8

Histology â typical lesions

Microscopic lesions in canine erythema multiforme are similar to those in human patients.3,8 Classic lesions include interface dermatitis, with cell death occurring in all epidermal (suprabasilar and basal) layers, accompanied by satellitosis (lymphoid infiltrates around apoptotic keratinocytes).3,6,7,8 Intraepidermal mononuclear cells are mainly lymphoid, but Langerhans cells have also been identified.3,8. In canine patients the follicular infundibular epithelium is regularly affected and hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis are common, which is not the case in human patients.3,7,8 Yager et al. further suggest that hydropic degeneration of the basal layer may not be such a prominent feature in canine patients compared to humans.8

Diagnosis and differential diagnoses

Erythema multiforme in the dog includes a wide range of clinical lesions, leading to a long list of differential diagnoses such as urticaria, demodicosis, dermatophytosis, bacterial folliculitis, superficial spreading pyoderma and bullous autoimmune skin diseases.3,7,8 The presence of scaling-crusting lesions additionally includes superficial necrolytic dermatitis, zinc-responsive dermatoses or other cornification disorders as possible differential diagnoses.3,8 Diagnosis of canine erythema multiforme therefore is often based on a combination of anamnesis, gross, and histological findings.3,6 Yager et al. emphasize the importance of taking the anamnesis and gross lesions into consideration when giving a diagnosis of erythema multiforme.8

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Veterinary Pathology

Vetsuisse Faculty (University of Zurich)

Winterthurerstrasse 258, CH-8057 Zurich

Fax number +41 44 635 89 34

http://www.vetpathology.uzh.ch

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Haired skin: Apoptosis, transepidermal, epidermal and

follicular, diffuse, severe, with neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic interface

dermatitis.

2. Haired skin: Dermatitis, suppurative, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with diffuse moderate ortho-and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis and bacterial cocci.

JPC Comment: The contributor has compiled an excellent overview of the three entities of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrosis (TEN), syndromes about which there remains to this day a lot of disagreement in the veterinary literature. Comparison with the human disease has advanced knowledge in these chronic and occasionally fatal syndromes and provided an excellent starting point, but the differences in the human disease and its veterinary counterpart are profound as well. Moreover, the literature lacks a critical number of well-documented cases of these diseases, and many of the cases in the older literature may, upon further review in light of more recent advances in veterinary dermatology, may have been incorrectly diagnosed.

In spite of

significant disagreement in the veterinary literature from the last decade on

these uncommon diseases, there are considerable points of agreement (many

already mentioned by the contributor, but worthy of mentioning again):

1. Erythema multiforme (EM) and STS/TEN represent independent and different diseases,

rather than opposite poles of a spectrum of immune-mediated disease.

2. Both EM and STS/TEN are mediated at least in part (STS/TEN) or in toto by

cytotoxic lymphocytes directed against altered keratocyte antigens.

3. There is considerable overlap in the histologic diagnosis of these

diseases, and these findings must be closely correlated with clinical findings

and history for a definitive diagnosis.

4. The histologic diagnosis of erythema multiforme is not a straightforward

diagnosis and bears a number of differential diagnoses that should be

considered before this diagnosis is rendered.

The reliable diagnosis of EM via STS/TEN has been confusing in both human and veterinary medicine for years. Early attempts at classification of these diseases5 were based on human schema and proposed classification on five categories: type of skin lesions, distribution, mucosal involvement, systemic signs, and precipitating factors. Areas of significant variation include types of lesions (in which epidermal detachment is useful for identifying STS/TEN) and mucosal involvement (in which an absence of mucosal involvement is seen only with EM. It may, however be seen with EM, so its presence is not of diagnostic utility). On a purely academic note, one of the few differentiating factors between Stevens-Johnson syndrome (STS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (and likely the reason that they are so often lumped together) is that STS should have <10% epidermal detachment) and TEN >30%. Regarding mucosal involvement, several classifications have tried to characterize mucosal involvement, either due to severity or the number of mucosal sites affected, but this criteria is still under evaluation.1,8 Significant overlap occurs in the remaining categories.

There is also significant disagreement and uncertainty yet remaining in the exact pathogenesis of the lesions in EM and STS/TEN. EM is characterized by lymphocytic targeting of individual keratinocytes, which SJS/TEN lesions are lymphocyte poor, with extensive areas of epidermal necrosis and lifting. Early SJS/TEN lesions resemble the pattern seen in EM, while later lesions with large confluent areas of necrosis suggest a progression to either waves of apoptosis,8 soluble mediators of inflammation such as reactive oxygen species, granulysin, and soluble Fas ligand, or programmed cell death (necroptosis) A recent publication established the death of keratinocytes in TEN to be an apoptotic event, as seen in its human counterpart2, but this does not explain the complete pathogenesis of this disease.

As complex as the diagnosis of STS/TEN may be, the correct diagnosis of erythema multiforme may be even more complex due to the variable histologic presentation and potential differential diagnosis. Lymphocytic-driven keratinocyte apoptosis at all levels of the epidermis and indeed, full-thickness epidermal necrosis may also be seen in EM lesions. The potential for hyperkeratosis in EM cases (also known as âhyperkeratoticâ or âold dogâ EM) also brings cornification or clinical scaling disorders into the differential diagnosis.8 Luckily, true cases of this condition, according to the moderator, appear to be extremely rare in the veterinary literature. Moreover, cases complicated by other secondary bacterial diseases or opportunistic infectious agents (as illustrated by this particular case) pose an additional diagnostic challenge.

The moderator stressed the importance of a good history as well as an optimal sample (often from the center of the lesion in which devitalization and lesion development in the differentiation of EM/SJS/TEM on surgical biopsy. As these three lesions may also resemble each other on a single biopsy sample, in the absence of a good history and clinical distribution of lesions, the prudent surgical pathology may withdraw to a conclusion that the biopsy likely is within the EM/SJS/TEM spectrum, but refrain from the desire to place it in one of the three categories. In the cat, exfoliative dermatitis associated with thymoma (and even a few without) may also present as a cytotoxic dermatitis which resembles EM.

References:

1) Banovic F, Olivry T, Bazzle L., Tobias JR, Atlee, B, Zabel S, Hensel N, Linder KE. Clinical and microscopic characteristics of canine toxic epidermal necrolysis. Vet Pathol 2015; 53(2):321-330.

2) Banovic F, Dunston S, Linder KE, Rakich P, Olivry, T. Apoptosis as a mechanism for keratinocyte death in canine toxic epidermal necrolysis. Vet Pathol 2017; 54(2): 249-253.

3) Boehm TMSA, Klinger, CJ, Udraite L, Mueller RS. Targeting the skin â erythema multiforme in dogs and cats. Tierärztl Prax Kleintiere. 2017; 45:352-356.

4) Favrot C, Olivry T, Dunston SM, Degorce-Rubiales F, Guy JS. Parvovirus Infection of Keratinocytes as a Cause of Canine Erythema multiforme. Vet Pathol. 2000; 37:647-649

5) Hinn AC, Olivry T, Luther PB et al. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in the dog: clinical classification, drug exposure, and histopathologic correlations. J Vet Allergy Clin Immunol 1998:6:13-20

6) Itoh T, Nibe K, Kojimoto A, et al. Erythema Multiforme Possibly Triggered by Food Substances in a Dog. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2006; 68(8):869-871

7) Jubb, Kennedy, Palmer. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Saunders; 2016.

8) Yager J.A, Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparative review. Vet dermatol 2014; 25: 406-e64.